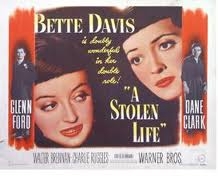

A Double Life: Bette Davis’ Twin Roles, Part 1: A Stolen Life

Bette Davis was a star of the first order with a duality about her persona which was serially and successfully exploited by writers and directors throughout her long career. A Stolen Life (1946, Bernhardt) occupies a very special place in the Davis canon: it was the only one of her films that Davis herself produced under B.D. Productions. She had had a very public legal spat with Warner Bros. in the 1930s and set a precedent amongst actors fighting the restrictions (and payment) of their studio contracts. A sojourn in England during which she lost her expensive case encouraged Warners to re-hire her under apparently more favourable conditions although she still found herself in demeaning roles. Her loss (legal and financial) was famous but it paved the way for future production successes amongst actors. She fearlessly went on suspension many times in order to achieve the roles she wanted and won two Academy Awards. Her feisty persona became authenticated through her performances and she was always associated with the role of the independent woman. A Stolen Life was her sole production venture and as such warrants analysis. Davis’ career, which lasted from 1931 until 1989, maps across the major developments in the sound era, from its commencement to its demise. A trained theatre actress, she initially worked at Universal Studios but soon became a staple at Warner Bros., where she achieved stardom in The Man Who Played God (1932) opposite George Arliss, after she was initially marketed as a comedy coquette and then as a result of the studio strategy of ‘off casting’ became a vamp, then alternated that with ‘good’ roles intended to deploy her abilities beyond the readily differentiated image (Klaprat in Balio, 1985: 356; 372-375). Two years later she consolidated that with glittery blonde eroticism as she played her first controversial Maugham heroine in Of Human Bondage (1934, Cromwell). She would successfully interpret Maugham again in The Letter (1940, Wyler). She won her first Academy Award for Dangerous (1935) in the dazzling role of a theatre actress who was maintaining a double life as an addict, allegedly based on the tragic Jeanne Eagels; and subsequently for Jezebel (1938, Wyler), a showy part that served as a placebo for losing the role of Scarlett O’Hara and in which she again played a dichotomous character of an outrageous Southern belle. Despite her position as the Queen of the Warners lot, it was the first year she obtained star billing. Her retreat into more obviously mannered performances took place at the end of the 1930s when her characteristic tics become more evident in women’s melodramas and her brittle movements were more focussed and she is shot even closer than before, bug eyes declaring a strangeness that beguiled and fascinated. It seemed that the camera was a little more in love with her as a brunette (her natural hair colour) and now the audience was getting further into her psyche even as her body’s actions seemed to be pushing them a little further back. Her strategy to accomplish the roles she desired carried great penalties for her, personal and financial. The role that Warners played in this reading of star as author is therefore primary and one of the melodramatic heavy variety.

By the end of World War 2 Davis had set herself up as the people’s actress – she helped put together the Hollywood Canteen, where film stars served food to and danced with servicemen and offered them succour from tours of duty. It was a situation that created a little romance as well. Those years were not the best of her career albeit two standout roles made up for the poor ones –Regina in The Little Foxes (1941, Wyler) in which her ambiguity belied her perceived evil in the Hellman adaptation; and in Old Acquaintance (1943, Goulding), a raucous delight, she played again on the potential of her duality in a John Van Druten tragicomedy that pitched her against that most histrionic of actresses, the brilliant Miriam Hopkins, in what was a comment on their pre-war hit, The Old Maid (1939, Goulding). A Stolen Life came about directly after the war’s conclusion when she was once again seeking control of her career. Davis said of her role as producer on the filmmaking team, “I didn’t want them to just do as I said. I wanted them to consider it. I wanted them to defend their position, not just to give in. Then, I wanted the director to direct, and for me to be an actress. I discovered that being the producer, too, didn’t free me. It encumbered me.” (Chandler, 2006: 173)

Kate Bosworth is a New Englander with a holiday home kept by her guardian Freddie at Craven Cottage, Martha’s Vineyard. She misses the ferry to the island and hitches a ride in a boat with a taciturn engineer Bill Emerson (Glenn Ford) who is working temporarily at the lighthouse rather than taking a fancy well-paid job elsewhere. She immediately draws his caricature and we know she has artistic ambition. She sees in him an amiable fellow loner. She arranges to humorously blackmail the lighthouse keeper into sitting for a portrait every day for a fortnight by acquiring a ship in a bottle from a local antiques store that he cannot afford in order to complete his collection. She barters with him, amusingly. The daily trips mean she can see Bill regularly and they start to go out for comfortable dates. He takes her to a bluff which is his favourite part of the island and says he wishes he was a painter so that he could capture its beauty; she says glumly that she lacks the talent. Her identical twin sister Pat is in the cottage staying with their guardian. Pat expresses curiosity about Bill. Pat ambles onto the dock for a luncheon date the following day with a wealthy beau and when Bill sees her he mistakes her for Kate and she goes along with it and responds pleasantly to his comment that she’s all dressed up –a comment he could never make to Kate, who has no interest in fashion. They have lunch at the cottage where Kate comes upon them and she senses that she has lost him. Pat ensures to take the same train to Boston as Bill when he is travelling there for business. She then attends a barn dance (apparently evincing “a sudden passion for the bucolic,” as Freddie declaims) and manipulates him once again. Kate is devastated. The engagement is announced, the wedding takes place, and Kate retreats into painting.

Kate’s dark heart – her twin

Davis was always a conventional film actress –lacking the remarkable inscrutability of Garbo or the fabulous sheen of Kay Francis; the rarefied air of Claudette Colbert or Loretta Young’s implausibly perfect beauty –she had theatrical technique, mannerisms, tics both vocal and facial, bodily actions (primarily strutting) which could be as stiff and complex as some of her characters, darting eyes, clenched fists. She was always acting. She also had overpowering presence and overwhelming charisma, an innate attractiveness that belied her unusual features and a gaiety that charmed. There was always a sense of danger and the unexpected about her performances, usually because they depended on her accessing two distinct parts of her acting armoury. She fizzed with life and emotion and blunted any opposition with the sheer force of her performance. Her eyes alone are legend (and the subject of a power rock song), her raucous wit a Hollywood fact, her bitter rivalries worthy of her opponents (Miriam Hopkins, Joan Crawford) and her prolific love life the stuff of romantic drama. The travesty of her daughter’s betrayal late in life she lamented loudly and forlornly. Davis can perhaps be criticised for many overly mannered performances but in A Stolen Life her movements and use of facial expression greatly aids the way in which she plays both of the characters differently and then assumes the identity of one twin alone with a masochistic edge of darkness. In fact it boasts perhaps her most subtle assumption of actorliness, her most moving portrayal of loss and the most convincing of her dual roles. The title is doubly expressive: of the life that Kate should have had with Bill, which Pat steals; and of the life that Kate duplicitously takes from Pat after she drowns and Kate impersonates her while being the victim of a simple case of mistaken identity, which she does not deny, after initial attempts to do so are put down to her illness and confusion following the death of her twin, Pat’s body remaining unrecovered.

The theme of the good twin and bad twin was popular in the late 1940s, probably owing as much to the introduction of psychoanalysis into everyday discourse as to dramatic possibility; and the desirability of having a star actress, invariably a troublesome one like Davis, or Olivia de Havilland, who emulated her in her wars against Warners, doing double duty, undoubtedly lured by the potentially Academy Award-winning such turns might indeed provoke. It seemed that Warners knew how to extract value for their precious investments: Davis and De Havilland mirrored each other’s career moves in more ways than one. De Havilland in fact did the good twin/bad twin act in The Dark Mirror (1946, Siodmak) the same time as Davis was making A Stolen Life. They had in fact been paired as the good sister, Roy (De Havilland) and the bad sister Stanley (Davis) in In This Our Life (1942, Huston) a study of duality which was by then commonplace in women’s films. They had already played opposite each other in the backstage romantic comedy It’s Love I’m After (1937, Mayo); and they would again be paired in the Gothic hag cycle by Robert Aldrich in Hush… Hush Sweet Charlotte (1964), a phase of filmmaking initiated by ??What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? ?? (1962, Aldrich), pairing Davis with Crawford in a satirical if ultimately tragic film that seemed to leach the truth about the sad twilight years of Hollywood actresses’ lives, eking out their early retirement playing cards and endlessly luncheoning at the club, going quietly mad with nothing of consequence to do after a professional life cut short by being over 40 (oftentimes much younger). Davis’ success rested upon those qualities which enabled her to access and portray the complex dimensionality of a role such as the Bosworth twins. Her career clearly demonstrates that from role to role she succeeded best in roles which were divided, dualistic and sometimes extreme in their range of emotions.

Bedtime stories

The double helix of reflection, refraction, imitation and fakery that the Bosworth girls offered was an obvious attraction: here she could play both the good and the bad woman; the sexual predator and her victim; the vicious, acquisitive twin versus the sensitive, generous one; the expressive versus the repressed; the real one and the fake one. All these elements were present –in the same script. The dichotomy of such roles –even within each of them, there are dualistic terms of expression– expressed the totality of the range she had thus far been permitted to express onscreen. It encapsulated her previous successes, providing here with a rare opportunity to achieve in the same film a kind of performativity rarely allowed a major actress. It was also an opportunity for the immediate post-war audience of women who had finally achieved parity during the conflict and were now back to the mind-numbing routine of domesticity to see their wish fulfilment amplified by their favourite star, times two, living out their lives on the big screen. This was a role that afforded its female protagonist to have it both ways. It was to prove an astute judgment on Davis’ part– ultimately her greatest financial success.

Kate upsets Pat’s plans for lunch

The film’s glorious locations –an extravagant ‘cottage’ in Martha’s Vineyard, the kind of 10,000 square footer getaway that only occurs in Hollywood films; an astonishing townhouse in Boston; a chi-chi art gallery; the dingy flat where grouchy gifted painter/mentor Karnock (Dane Clark) plies his art; the fog-enshrouded cliffs and the dramatic trips to and from the isolated lighthouse– all reinforce this film’s status as a major production featuring one of the era’s biggest stars. The juxtaposition of these shifts in scenery with their claustrophobic, chintzy interiors and the crashing waves of open sea embrace the film’s raging torrent of Kate’s concealed emotionality. The filming style, however, utilising the tropes from conventional genres such as Gothic, horror and noir, complicate its message while slyly bowing to the trend of the psychoanalytic, which was now becoming such a powerful cultural influence. The film has the air of both a Gothic and film noir: it is shot in shadows, in contrast, in fog and the entire sequence in Karnock’s flat seems to be from a horror film, inclining us subtly towards the moral morass we are entering. It is tonally dark, cutting back and forth from unhealthy shadows to the open air. We are clearly getting a visual treatment of Kate’s inner torment, in keeping with the trends of cinema at the time. Intensity of identification is ritually inscribed into the film’s strategy through a visual scheme that utilises the tropes of those generic types and clearly communicates to the audience the inner horror she experiences at Pat’s betrayal and the loss of Bill – even if she cannot admit it to herself or act out any kind of individuating motive that might free her of malign influences inherited from her family. Her happiness is at sea, on the cliffs, prowling the paths alone, hat perched atop her bobbed haircut, fashion be gone. This symbolic summoning up of the uncanny in Karnock’s home triggers the concept that Pat is Kate’s Demon Other –a more precisely stamped alter ego and vicious doppelganger. Karnock forces her to confront her feelings: Kate is the true, decent if incomplete Self, Pat the motor for a spiral into imitation– which is certainly not a sincere form of flattery, rather a descent into excess for the re-making of Kate-as-Pat. In this sequence we understand what Kate herself clearly does –that she is Pat’s gloomy alter ego, an incomplete person, a non-sexualised actor in an adult drama in which she dare not participate. It is her acknowledging of this at Karnock’s insistence that triggers her journey into transformation that marks the woman’s film.

The return of the repressed

In a sense, Bette Davis was always making this film, or a version of the story at least. In The Old Maid she pretends to be a nasty unattractive aunt to her own daughter in the house of her loathsome cousin played by Miriam Hopkins – who had dumped the man that became Davis’ own great love and left her pregnant while he died on the battlefield during the Civil War. Effectively she has to embody two very different characters here. Her own life had a dual aspect: she was a respected theatre actress whose fame came (at a price) in cinema; she had a vicious temper which at times led her to doubt her own mind; her younger sister Bobby had ambitions to be a film actress which she helped quash; Bobby’s mental health problems proved an expensive problem for Davis herself as her sister was frequently incarcerated in asyla for what appeared to be manic depressions, which Davis feared her own temperament might also be hiding. (At times the forcefulness of her highly strung performing style would leave one with the impression of hysteria). Both her sister’s and mother’s expense accounts would lead her into frequent issues with indebtedness which would get something of an airing in The Star (1952, Heisler), a story allegedly about Joan Crawford but had more than a ring of truth for Davis’ own heady familial experiences at that time. Later in Dead Ringer (1964), Paul Henreid, her romantic co-star in Now, Voyager and Deception (1946, Bernhardt) would direct her during her Los Angeles Gothic phase as an identical twin who murders her wealthy sister out of revenge and then assumes her identity. It was a gloss on her earlier performances in A Stolen Life and also acknowledged the authenticating power of real and reel life collapsing in our understanding of the social function of a major star; not quite a remake, perhaps, but a re-imagining, West Coast style.

Therefore in our understanding of Davis as star it often depends on our acceptance of oscillating performances within the same film and sometimes even in the same role. In Casey Robinson’s stylish adaptation of Olive Higgins Prouty’s ugly duckling bestseller Now, Voyager (Rapper, 1942) Davis essays a summation of her career thus far – the flashback to her flirty, sexy, twentysomething self; the bullied spinster as a clever reference to her bifurcate role in The Old Maid; and her contemporary, free-living persona camouflaged from her Boston Brahmin family by the codename ‘Camille’ in which she is her true self, masking her affair with a married lover Jerry (Henreid) while caring for his daughter whom she treats as her own (her mother being conveniently incarcerated in a lunatic asylum). On the surface, and after her monstrous mother’s death, she is now the richest woman in Boston (paradoxically due to her mother’s will), living another very secret life, no longer the troubled model-maker but the lover of a married man, nurturing his daughter as her own mother sought to destroy her A double life, doubly encoded in a double helix of deceit (and psychoanalysis).

The good twin and the helpless man

Davis got married (again) in the late 40s and gave birth to a baby girl, after which she aged overnight. If the career dividends were now less reliable –the disastrous over-played melodrama of Deception, with shout-offs staged in a couple of different living rooms betraying the film’s ill-adapted theatrical origins and regular co-star Claude Rains shamelessly stealing the show; the long-haired flirt look essayed in Beyond the Forest (Vidor, 1949) which was clearly a step too far for an actress starting to lose her looks in what was in fact an extraordinary cri de coeur on behalf of unhappily married women through the ages –all was to be eventually redeemed by her masterful sleight of hand casting due to Claudette Colbert’s back injury in the role of the protagonist in All About Eve (Mankiewicz, 1950). It was not the titular role –that was played by Anne Baxter– but it rewarded Davis with a magnificent two-fold part: theatre star Margo Channing is a babe in the woods compared with the old-fashioned venality of Eve, a cunning no-name tramp who tramples her benefactor to become queen of the stage in a tale allegedly based on tittle-tattle about the relationship between Tallulah Bankhead and the young Lizabeth Scott on a Broadway production some years earlier. (There is also a version of this story concerning Elisabeth Bergner, the heroine of the first screen version of A Stolen Life. But that is another twist of the doubling effect.) The fact that Bankhead’s playing of Regina in The Little Foxes on Broadway was epoch-defining may have been another skew to Davis’ joy in the earlier film role (1941), a majestic performance although her take on it was diluted by her former lover William Wyler’s direction (Dyer, 1998: 147-50). Bette Davis, it seemed, always did things twice. It was enough to make Tallulah Bankhead scream.

Freddie stops Kate at the barn dance

Margo is a middle-aged old-school actress, a star to the fingertips, full of sound and fury but fundamentally decent and completely unable to see the whirlwind of deviance coming her way. Once again, Davis pulled off a panoply of character tricks to achieve a performance of depth and humanity which nonetheless has its share of camp classic one-liners, mainly thanks to the asides and broadsides delivered by herself, George Sanders and the redoubtable Thelma Ritter, the film’s own Greek chorus (girl). Davis once again shone in a dualistic role –an aggressive-passive ageing actress riven with self-doubt and plagued by thoughts of retirement, saved by the attentiveness of a caring younger lover who is also her director– prime fodder for the grasping ingénue with sex on her mind and awards within her reach, using Margo’s own clothing to dress up her ambition as servitude, a clinging limpet who leeches Margo’s lifeblood like a vampire. Robert Corber deconstructs the role that Margo played in the remaking of Davis’ career. By now her quirky looks had caught up with her post-partum self; she met Gary Merrill on the set of the film and they commenced a tumultuous life together; and her Bankhead imitation (Davis maintained it was just a coincidence because they had the same hairstyle at the time) won her acclaim. For Corber, this is a Cold War movie that foregrounds Lesbianism but also highlights the performative aspects of all femininity and links Margo with Lesbianism through the infiltration by the masculinized Eve of Margo’s household and the manipulating of her domestic arrangements, already run by the ex-vaudevillian, Birdie (Ritter), herself a Hollywoodized version of acceptable Lesbianism. Margo’s identity is threatened in such subtle fashion that she becomes unsure at this destabilising influence; and her own role in terms of femininity threatens ideas about female spectatorship. This is dramatised in terms of performativity and the projection of normative institutions of heterosexuality in opposition to the non-normative option expressed by Eve, who also toys with the affections of acerbic critic Addison De Witt (Sanders). Davis’ famously husky voice (another analogy with Bankhead) was attributed to her hoarseness on showing up to the first day on the set and director Joseph Mankiewicz’ subsequent insistence that she keep her vocal delivery in a low register for the remainder of the shoot. It simply added to the scandal that she was getting away with doing a Bankhead imitation. Her camp delivery of certain lines added to the idea and also complicated the film’s message about femininity: the final scene of the new version of Eve, ‘Phoebe’ (Barbara Bates) admiring her proliferating reflections in Eve’s multiple mirrors could even be said to deny the traditionally stable image of heterosexual femininity and institution of marriage which Margo is attempting to achieve. This was a truly startling portrayal of womanhood, with Davis’ brilliant performance at its centre. She had made female independence, ambitious spinsterhood and platonic female bonding a viable option for women in a wide variety of roles, now she was aligning herself with old traditional in the face of queer opposition. David Thomson calls her performance a “curdled cocktail” (Thomson, 1994: 172). And yet, there was something so terribly camp about the construction of her role which was connected in the main with her typical style which basically transmitted outdatedness so that one couldn’t be quite certain. On the one hand she was endorsing staying at home as the wife of a successful man; on the other she was doing it in such a camp fashion that she was effectively distancing herself from the prevailing acting norms. It was such a great performance and her acting powers so constantly acknowledged within the diegesis (and without, courtesy of her twenty years of marketing at Warners) was she sending herself up– or the institution of marriage? It would hint at what was to come in her role in Baby Jane? more than a decade later, another iteration of the dangers of stardom, at any age. For now, it was a game-changer sufficient to relaunch her career (Corber, 2011: 30; 36-46; 136-7; Chandler, 2006: 190-2).

Helen Hanson draws out the many complex strands of American womanhood into a portrait of female subjectivity and national denial that is exacting, as the femme fatale of film noir and the wronged victim of Gothic get an airing not merely as generic characters but generative figures in their own right in her compelling study, Hollywood Heroines: Women in Film Noir and the Female Gothic Film. The process of audience identification, gender perception and positioning, mode of address and narration, form the structural framework of her examination of these stories of fear, romance and suspicion. Setting out to right some contextual wrongs, Hanson sheds light on some of the fringe films of both noir and Gothic in order to stretch out the canonical text’s potential. The role of the doubling has a double role – it is both life-affirming and threatening and can represent the repressed and the excessive. The difficulty in Gothic narratives arises when the portrait represents a likeness of the heroine –in A Stolen Life, that likeness belongs to Pat. (Hanson, 2007: 92-6). However the film’s narrative simultaneously refuses the Gothic line that repression leads to madness –Kate is devastatingly sane, if not quite self-possessed. It is her recognition of her limitations that both assures her destiny and then re-invents it, replacing her antic, hedonistic, fashion-plate sister with a more down-to-earth, sensible, conventional type, however unintentionally. It is her triumph that bends and twists the narrative form and makes the film a success.

Sexual excess, performativity (outside the issue of voice, which was one of Davis’ defining characteristics with its brutally precise enunciation) and desire are all crucial components of both noir and Gothic horror genres and when Karnock accuses Kate of not being a complete woman, she reacts as he anticipated: “That always gets them! You can criticise a woman for her work but suggest she’s not a ball of fire …oh boy!” His presence functions as a lever to release her innermost self: the part she wants to hide – her evil twin, her dark half, her Pat. The fearfulness she experiences in her realisation leads her to plunge into painting – as opposed to sex. The film’s midpoint sequence illustrates this completely. Freddie visits Kate at her art studio to confirm the rumour is indeed true that she has “ fallen under the spell of “the Rasputin of the paintpots.” Bill contacts Kate to help him choose a birthday gift for Pat – forgetting that it is Kate’s birthday too. She plays the ‘wife’ role for the first time – he asks her to hold an elaborate negligée up against her figure and reckons Pat will look perfect in it. Kate expresses surprise that he is on his way to Chile for business: “I can’t think of you away from the island.” He’s doing it for the money – for Pat. Now he is role-playing too.

Pat and Bill

Adapted by Margaret Buell Wilder from the novel by Karel Benes, originally published as ULOUPENY ZIVOT, the practised hand of Catherine Turney was assigned to writing the screenplay, the second version in the English language following the British adaptation starring Elisabeth Bergner in 1939. Turney was a hit playwright with productions on both the London and Broadway stage and had also written several books, novels and historical biographies. She was hired by Warners specifically for the films of both Davis and Crawford, Davis’ great rival. She did some work on Mildred Pierce (1946, Curtiz) which went uncredited; as did Wilder’s contribution to the same film. Wilder had made her name with her book Since You Went Away (1944, Cromwell) which David O. Selznick produced and co-wrote. She got an Additional Dialogue credit on the adaptation Young Widow (1946, Edwin L. Marin), which was billed as “The World’s Most Exciting Brunette!” –who of course turned out to be Jane Russell. Her last work on her contract was a Maria Montez extravaganza, The Pirates of Monterey (1947, Alfred L. Werker).

Turney also did uncredited work on Roughly Speaking (1945, Michael Curtiz). She was first paired with director Curtis Bernhardt on a Barbara Stanwyck film, My Reputation (1946), which she adapted from the novel INSTRUCT MY SORROWS by Clare Jayes. It was the first film to show a married couple’s bedroom with a double bed since the Production Code was introduced. On The Man I Love (1947, Raoul Walsh) she co-adapted and wrote the screenplay (with a little help from W.R. Burnett) from the emotional backstage novel NIGHT SHIFT by Maritta M. Wolff. She wrote another Stanwyck film, the mystery thriller Cry Wolf (1947, Peter Godfrey); and 1948 would bring her another Bette Davis project, Winter Meeting (Bretaigne Windust), another adaptation, this time from a novel by Grace Zaring Stone. Her last major credit was with Sally Benson on another Stanwyck film, No Man of Her Own (1950, Leisen), based on Cornell Woolrich/William Irish’s novel, I MARRIED A DEAD MAN, in which the star plays an abandoned woman who takes the place of a pregnant heiress. Turney’s forte in essence lay in the writing of strong, interesting, liberated modern women’s roles in glossy well-made romances with a hint of outrageousness, a sprinkling of fantasy and a harsh dose of realism to satisfy the censors. Turney said of writing for Warners at this time:

They [Warner Bros.] recognised the fact that a woman could handle a story about a woman’s troubles better than most men could. Anyway, you can rest assured that if the studio didn’t think the woman did a better job, she wouldn’t have been there for very long… One of the reasons they hired me is that the men were off at the war, and they had all these big female stars. The stars had to have roles that served them well. They themselves wanted something in which they weren’t just sitting around being a simpering nobody … [their characters were women] battling against the odds. (Hanson, 2007: 9)

In A Stolen Life the action moves to the United States; the sister’s relationship is put under a spotlight that focuses on the rampaging sexuality of the one and the withdrawn, subtle inclinations of the other; and it conveys the hidden contempt of the one for the other utilising the art world and the idea of (self) portraiture which is both opaque and mysterious despite its apparent evidence about talent, ambition or the activities of individuating and separating in achieving a successful self. This locates the film in that cycle of cinema which devolves upon the issue of psychology and is also summed up in Freddie’s advice to Kate to go after Bill – a kind of Dale Carnegie spin on Sigmund Freud. It is clear in this binary structure that the idea of the twin and the role of genetics is being referenced – the one being something of an incomplete replication or duplication of the other (Pat being the more complete, the more active and go-getting, the more clearly sexualised); Kate being perceived as mere imitation, decent, pleasant, unambitious, proper: to our eyes they are (obviously) utterly identical –but in the film’s diegesis, Pat “is the loveliest bride of the year– or any year!” It is patently absurd of course but in the context of the film it is how we are encouraged to view Kate –and it is Davis’ acting skill which makes us believe it. According to Basinger, however, in identical twin dramas it is the norm for the more conventionally or appropriately behaved twin to be deemed the more beautiful; whereas here it is the nasty, avaricious one whose sexuality is on permanent display, her clothes a signifier of her overt desire. In short, Pat is a sex object and that is the only kind of woman that men understand (Basinger, 1993: 86-7). Therefore the revelation of Kate’s animus by Karnock –a plot point which layers the psychological approach and also helps reverse Kate’s trajectory from inner-directed to outward-seeking– fulfils narrative needs very cleverly. Introducing another man –who doesn’t seem to wash or shave and is clearly an iteration of animal sexuality, and he is a talented painter, as well– helps us see Kate in another light. She wants to be a better artist and her willingness to take on a man who challenges her in every facet of her personality –including her covert sexuality– makes her less of a fake Pat and more of a real Kate, a whole person in this ghastly tale of sibling rivalry.

The distortion that Pat has made of Kate is reduced as we then see Karnock’s perception of Pat – in this hall of mirrors experience he recognises her duplicity and reads her actions through Kate’s withdrawn behaviour. The divergence of the twins is signalled in his compulsion to tell the truth. But even for Karnock, there is no real blurring of identities because even his perception of Kate-as-Pat is dimmed, claiming that the women look different around the eyes! This is a drama of mistaken identity – and it shouldn’t be. It is a drama of difference. As Basinger states, Kate cannot win a man because she lacks both fashion and glamour (Basinger: 89). The dangers of psychological literalism (as opposed to realism) are of course replete in this reading but the generic signifiers are emphatic in creating for Kate the possibility of change, of ambition and of fulfilment. Crucially these possibilities are correlated in the visual patterns of the film’s composition –because she wants to be an accomplished artist and she works hard with Karnock to try and achieve it. It is this desire, to fill the gap between what she wants and what she needs, that provides the narrative fulcrum. And it is partially her lack of talent that prevents her from achieving this desire; and partially her sister. She must decide which she wants more –success in art or success in love– and she has to take a course of action to decide which she is more likely to obtain. It involves a metamorphosis and a separation – the mark of the process of individuation. In the conventional Hollywood melodrama this involves breaking away from the (monstrous) mother, which we know Davis as capable of achieving from Now, Voyager. Here, she must break away from her mirror image and in order to be her true self she must pretend to be someone else entirely (Byars, 1991: 152-3).

Karnock introduces Kate to real art

After the encounter with Bill in the department store, Kate returns to her studio – which now resembles Karnock’s own– dimly lit, shadowy, murky. He essays the role played by Pat earlier in the film – snuggled up in a chair, baiting Kate, in this return of the repressed. This is the centre of the film’s action and the key element of the midpoint sequence. “All this art stuff has been a substitute for something, hasn’t it,” he goads Kate. She responds by saying she knows she’s a third rate artist. “Always running away,” he continues. “No wonder you lost him. You’ll never land a guy all closed up inside like this!” He is playing the role of psychoanalyst, she the analysand. “But I wasn’t always like this – people change!” Kate protests. It is her declaration of intent. His conceit accuses her of lusting after him but being afraid to go for it. Then he makes the film’s big speech: “Man needs woman, woman needs man, that’s basic. Everything else starts from that – art, music, the whole works – only women like you want to make something important out of it. You want a guy to stifle themselves for you – a grand passion and all that baloney!… Don’t go female on me, get wise to yourself.” She concedes that he is right and as she succumbs to his forceful embrace, she withdraws. It’s not him she wants – and they both know it. She apologises. “I guess it is the grand passion, or nothing. I think I’m going to the island for a while.” This period of darkness is necessitated by her internal journey – a journey to the very depths of her being, which the island of course represents. Her inner-directedness is immediately juxtaposed with Pat’s interminable quest for liveliness and incident: when she arrives at Craven Cottage, Pat opens the front door. She has taken up sailing, another example of her zest for sensation, her inability to deal with any level of boredom. “That I want to see,” comments Kate drily. This is the end of the film’s first half.

The two sisters proceed down to the dock together the following day, dressed identically for the first time in the film. At the level of plot the film recommences here. Kate now matches Pat for fashion and glamour – even if it is only of the seafaring variety. The figural is central to Gothic iconography, and here it is living – but not for much longer. Kate’s metamorphosis requires that she becomes a kind of Trojan horse. Pat claims she would have died of boredom if she hadn’t started sailing and in any case she wanted to meet up with the old gang again: she has a lunch date with a wealthy beau tomorrow – which is where she entered the drama in the first place, on the dock, mis-identified as Kate, and stealing into Kate’s life in a masquerade for Bill to which he willingly succumbs, hapless in her destructive web of desire. This, then, is an action replay of part of the film’s first half – but with a satisfying twist.

Pat – all at sea

Out at sea, Kate allows the neophyte sailor to take the tiller and a storm whips up. Pat thinks it’s exciting. Kate tells her, “It’s getting really nasty Pat, we should go back.” Pat shouts back, “Not on your life! I’ve always wanted to sail in a storm!” Kate responds, “You’re crazy!” as they wrestle with the sails. The fog descends upon them. “All we needed was the fog,” moans Kate. Pat concedes: “You were right, we should have gone back.” They head for the lighthouse, buffeted roughly by the mounting waves, the foghorn sounding out in the tempest. The keeper spots their struggle through his binoculars – double vision. Then Pat falls from the boat and slips from Kate’s grip –a comment on the slipperiness of their blurring identities, established through clothing– leaving her wedding band in Kate’s fist, the symbol of the one experience that has brought their lives to a deathly intersection: Bill.

When Pat dies sailing in the storm and it is not Kate’s duplicity but other people’s misperception of who she is (she is found clutching the wedding band) that convince them she is Bill’s wife. Pat has died because she is not good at something – and Kate is finally better at the one thing that matters: survival. Pat has encountered (Super) Nature and it has finally quelled her desire for chaos and eventfulness: it has literally taken a force of nature to finish her off. Kate is baptised by the waters, more at home in this domain, the natural, the solitary, the give and take of the waves and the ebb and flow of the sea that surrounds her beloved island being something she can wrest with more ease. The interplay of the film’s Gothic and noir elements necessitates a death: it turns out that the nice twin is the femme fatale. Kate plays along with other people’s interpretations, as she has always done. But for the first time in her life she sees the opportunity to achieve something she would not ordinarily have had – marriage with Bill. It is a kind of rebirth, or, more correctly, an inversion of truth. It is here that the parallels of the twins’ desires converge: Bill returns from South America upon his sister-in-law’s supposed death and the lived reality of Pat’s sexual proclivities and penchant for promiscuity emerges –their marriage is a sham and is about to be ended by divorce. They have been living apart for months; Pat was at the cottage because they had agreed to separate when Bill found out about all her ghastly affairs. The play of doubling around the doppelgangers is immediately complicated yet again by the splitting of perception from reality. Pat’s existence is not just a disturbance in Kate’s life – it is a transgression in many lives around her and she appears to exist in multiple forms (even in death), a miracle of splitting and mimesis, gene doubling and drama, a double life. Kate therefore has inherited from her not just a double life and the life of her actual double, but a vicarious one. The distinction from Pat is now not just that of a gloomy alter ego but a moral one. Kate, now playing Pat, has to enact a series of repetitive compulsions –that is, in psychological terms she must express a desire to repeat a trauma in order to overcome it– by living Pat’s life, or a version thereof. The circle of imitation and repetition seems endless and intolerably unfair. In movie terms, Kate is a poor stand-in (or stunt double) because the dog can tell the difference straight away. She has to befriend him – unaware that he loathed Pat and loves her. It is this simple demonstration of kindness that eventually gives her away, that and her innate decency. As Ginger Rogers once remarked to Fred Astaire, “Honey, dogs have an instinct for the right people” (Shall We Dance, 1937, Sandrich).

The film’s final act is a summary of another part of the first, replaying it as it ought to have played out. She arrives in the fog at Craven Cottage, the horn sounding from the lighthouse, greeted by Freddie, who after a short exchange tells her he knew it was her, and not Pat, almost immediately after the accident. He cannot believe she could live a lie. He cautions her that for a man like Bill, the truth is “the only way.” She walks to the bluff, shrouded in mist, Bill’s voice ringing in her head about wanting to capture it in a painting. The waves crash against the rocks below. Then the real Bill approaches her on the cliff path and they embrace and he says he was in love with Pat but it was “never right.” The End.

If the diegesis expresses shifting modes or registers of performance, then Kate’s role is to play a different version of Pat than that which would formerly have been possible. Kate’s own fundamental New England decency means she is losing control of her identity – her true self – in an altering world which is filled with Pat’s lovers and Bill’s disgust. This is not the island. Enacting desire is not a simple task, it is rendered infinitely difficult by the consequences of her late sister’s ritualised betrayals and the natural consequence of ritual betrayal is a sacrifice of sorts. Pat’s own life has been given up to the ocean. Now Kate realises just how different she is from Pat. It is eventually a relief to relinquish an identity which could never have been hers, in any version of their multiple incarnations.

The first piece of art Kate produces is a not very accomplished caricature of Bill Emerson when she meets him as he pilots the boat that takes her to the island after missing the ferry. We see Kate doing the portrait of the keeper at the light house, but only catch a glimpse; after Pat and Bill’s marriage her finished portrait is framed and exhibited at a privately financed gallery. Gatecrashing wisecracking painter Karnock (Dane Clark) sits beneath a portrait of a fisherman, a painting we have not seen her doing, so it is proof that she is taking her work seriously. After she reveals to him who she is, having endured his catty comments about the painter’s amateurism, she asks to see his work and they take a long busride across town to a hovel filled with wonderful work but he can’t pay for proper paper or oils. When they endeavour to work together at her studio so that she can learn from him and he can afford charcoal, we see her unsold portraits of the lighthouse keeper and the fisherman on the wall. The next portrait attempted by Kate is in concert with Karnock as her usual model pouts and complains about Karnock’s nitpicking.

The portrait exists as a signifier –a form of wish fulfilment on Kate’s part, of an action achieved by sheer willpower. It is doubly troubling by virtue of the fact that it is a living image, if a misrepresentation. It is an image of instability and danger. It is her twin sister who is the real portrait in the film, who has the art of living mastered, until nature stops her from wreaking further havoc on more innocent lives. We don’t see the hours of painstaking sitting and work that we are told have gone into the lighthouse keeper’s portrait, only the end result of Kate’s efforts. In keeping with her essential self, it is representative and true. And her concept of art is compared negatively with Karnock’s; while the lighthouse keeper’s own version of art is more straightforward and folkloric, in keeping with a mariner’s tradition of putting model ships in bottles, as if by magic; his collection dominates our introduction to Kate-as-Pat after the drowning – they frame the crashing waves on the rocks beneath the lighthouse, while she awakens to her new life as Pat. In a sense the portrait of the lighthouse keeper is a trope for what she wants to have with Bill, the marriage that could have happened if she had altered one fundamental part of her character – lack of aggression and ambition. Freddie tells her “You’ve got to fight….” However she is the passive component of the twins, Pat is the aggressor and victor in matters of the heart. It is the repetition of other people’s perceptions of Pat that aids the audience’s understandings of Kate’s fatal flaw – her identical twin sister. The visual and auditory rhymes established by the lighthouse – a horn signifying truth; enlightenment ironically descending upon Kate through the dense fog (it is also, crucially, the herald of Pat’s death); and its repetitive occurrence at important narrative junctures that conjures the murk that needs to be wrought through Kate’s character in order that she achieve individuation. She needs to balance her lightness of character with the combative, almost pathological darkness that her sister possesses and which is symbolised by the production design and lighting. Those aspects of the film that quote horror tropes reinforce the immanence of death – and its necessity – for Kate to become her true self even as her mirror image is clearly dramatised as something of a dislikeable, demonic Other. The formation of the female narrative and the iteration of female ideals within generic storytelling dominate our contemporary understanding of this type of filmmaking; issues of representation and gender conflict control our retrospective interpretations; and the challenge to dominant discourse cannot dispel our fundamental reading of a film of this nature – dualistic or otherwise – that it is a drama of sexual jealousy. What usually occurs in Gothic cinema is the will to power of the woman painted in a portrait hanging on a stairwell, the portrait indicating familial instability; then there is the simultaneous transformation from without to within by the protagonist traced in the narrative progression, indicated by dress (here, Kate and Pat are dressed identically immediately prior to the drowning). Unlike traditional Gothic films, the threatening female portrait is the living image of Kate. In A Stolen Life the portrait that Kate needs to complete is that of herself and she can only accomplish her goals in life and in art through Pat’s death.

The film’s strategy of narrative closure depends on the play of melodramatic elements which were already components of two other contemporary film styles cited: the female Gothic (highly popular) and the film noir (less so, at the time). In other words, female subjectivity is complicated by the actuated sense of female duplicity so common in these generic forms and the hapless male – who finds himself unable to do the right thing until it is already in place. This is a woman’s drama and involves a woman’s decisive actions. Men are just the patsies. In a broader sense, and conforming to audience expectations (as derived from extensive and long-term marketing research), Davis was playing the characters for whom she was now best known – the scheming wife or lover; and the good woman seeking to do the right thing. It’s just that they – and she – were now in the same film. They were even the same woman, in a sense, the corrosive grasping nature of the one complemented by the neutralising decency of the other. While Davis was noted for her tics it is notable that in A Stolen Life she turned in two quite subtle performances and was amply rewarded for her choice.