Paul Sharits: Expanding Cinema to the Beyond

A documentary film by François Miron

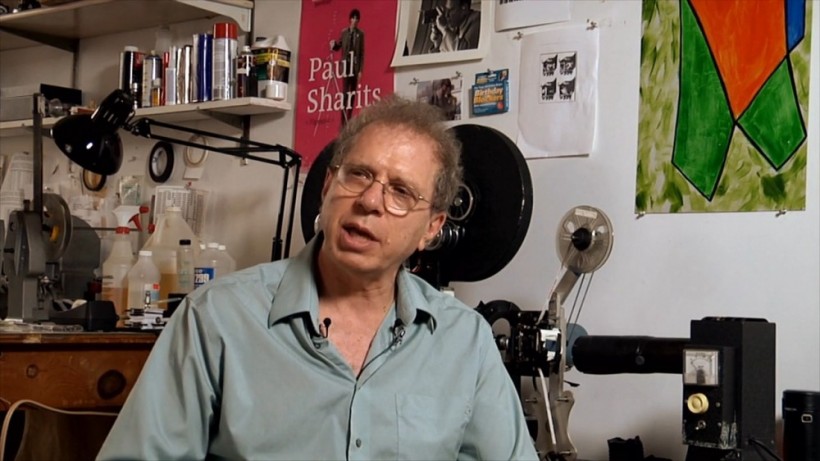

François Miron’s documentary on the experimental film artist Paul Sharits is, simply said, engrossing, captivating, stimulating, and innovative. Miron has been teaching experimental cinema (and cinema production in general) as a part-time professor at Concordia University for about as long as I have and Miron is somewhat of a cinematic polyglot, having taught film and made award winning experimental short films, fiction short films, a fiction feature film (The 4th Life) and now a feature documentary. In some respects Miron’s life parallels Sharits’, as he has had to battle his own personal demons for years, while maintaining the dedication and stamina necessary to completing films. As a teacher Miron was the master of the optical printer, which sadly has now departed the building after the wholesale digital revolution in the cinema department. But Miron’s film Paul Sharits is in some respects a dedication to the ‘old’ way of making experimental cinema, a nostalgic trip for celluloid heads to see so many people interviewed in their work or home spaces littered with old school film paraphernalia: take up reels, projectors, optical printers, bottles of chemicals, film stock, bins, cameras, Steenbecks, a veritable ‘analog’ world.

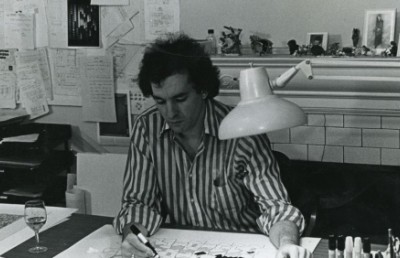

Bill Brand

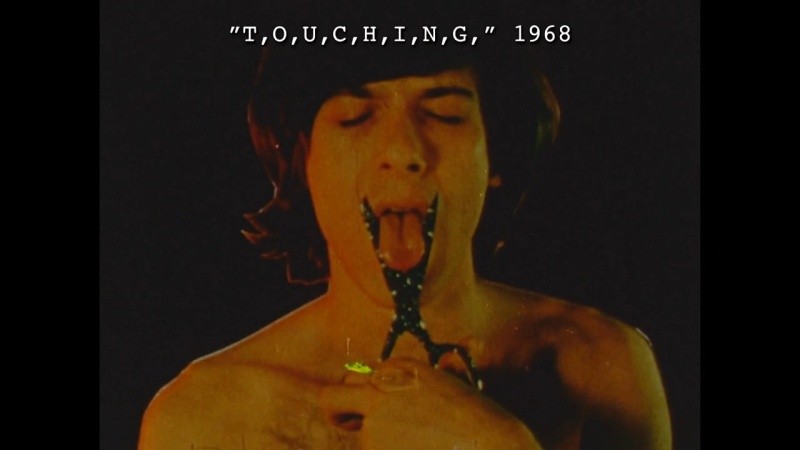

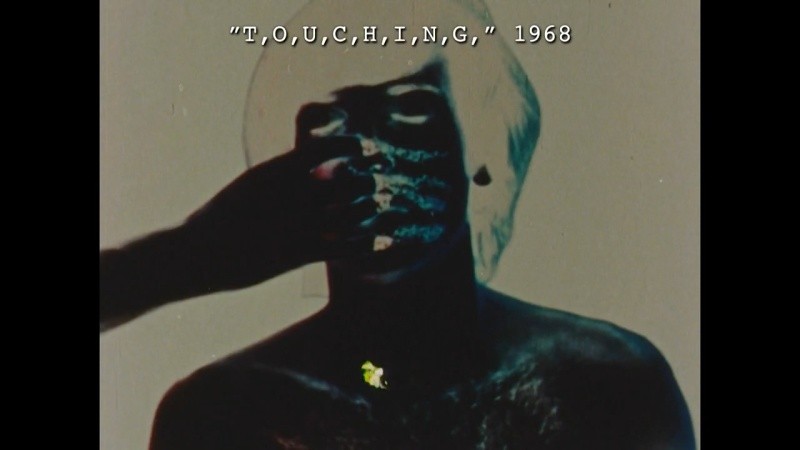

My own introduction to Paul Sharits comes by way of his twelve minute 1968 film T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G, which is always screened in one of our key undergraduate film studies courses at Concordia University. In a full year course that features well over 40 films, T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G, is, for better or worse, a film that students find hard to forget (and for some, hard to sit through!). I can remember the many occasions where former students who reminisce about the course ask me to remind them of the title of THAT film about the “man with the scissors to his tongue”! And I was pleased to see that Miron’s film begins with T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G,, and then cuts to Sharits making a comment that, through the edit, seems to be about T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G,, but may very well not be: “Only someone who’s completely mad would go on doing THAT”. The words could very well be in reference to Miron himself, and his dedication to completing this labor of love. But it also expresses exactly what makes T,O,U,C,H,I,N,G, such a brilliant film: like many great artists, THERE IS a ‘touch’ of madness in this film….and if the goal of great art is to destroy that which came before, then….”destroy, destroy, destroy, stroy, stroy….”

It is strange that while Morin’s film and its subject appear to be about a bygone era, the way Miron couches and treats the subject we get the equal sense that Sharits was an artist ahead of his time. Or at least, that his work as a filmmaker, painter, composer, sculpture and multi-projector installation artist speaks directly to the many facets of the digital revolution. Such hot recent labels as multi-disciplinary art and ‘expanded cinema’ seem to have been invented to describe Sharits’ work from the 1960s onwards. As Yann Beauvais writes on the official Paul Sharits website (moderated by his son Christopher Sharits): “Although Paul Sharits is primarily known as a filmmaker, his artistic practice was not limited to the realm of film-making. Painting, drawing, sculpture and performance all held a large place.”One of the joys of this documentary is in fact having the chance to see (even if not in their original context) some of Sharits’ other non-film art pieces; like his paintings, drawings, and his fascinating series of ‘frozen film frames’ (described as ‘filmstrip paintings’ by Beauvais). Sharits appears as an elusive subject, an introvert filmmaker who made aggressive, playful and complex experimental films during the heyday of the structural film movement, along with his contemporaries Michael Snow, Tony Conrad, Hollis Frampton, and a fellow Austrian structural filmmakers, Peter Kubelka and Kurt Kren. Sharits made his first film in 1962 (Wintercourse) and his final film in 1987 (Rapture), six years before his death by suicide in 1993 at age 50. Miron does not express this tragedy as a negative energy or dangerous ground, but instead paints the film in a melancholic hue, aided immeasurably by the original music score (and sound design) by Félix-Antoine Morin, which surrounds the images in a minimalist swirl of plaintive piano, and soft acoustic strumming, and electronic drones, only to switch to pipe organ (real or synthesized) for the rousing finale of the film, encapsulated by Bruce Elder’s rhapsodic eulogy of Sharits’ brilliance.

Bruce Elder

Miron’s film wonderfully captures what made Sharits such an important experimental filmmaker; there are testaments from his peers, colleagues, curators, academics, friends, all desperate to explain why Sharits impacted on them so much and why he is so vital to cinema. Some of these people who speak passionately and intelligently on Sharits (either on camera or audio) include teacher and friend Gerard O’Grady (who gives a moving account of finding Sharits dead in his house), artist/friends (Henry Jesionka, Woody Vasalka, Steina Vasulka, Stephen Gallagher), film scholars (P.A. Sitney, Annette Michelson, Stuart Liebman), fellow filmmakers (Bruce Elder, Tony Conrad, Richard Kerr, Bill Brand), curators and archivists (Robert Haller and Andrew Lampert of Anthology Film Archives, Chrissie Iles, Whitney Museum of American Art, Howard Guttenplan, Millennium, Pip Chodorov), MM Serra (director of the Filmmaker’s Coop in NY, and family (his son Christopher and daughter-in-law Cheri Sharits).

The film begins at the beginning, with his birth, and ends somewhere near his end. Morin does not dwell on the darker side of Sharits’ life but places it within the whole of his art, evident in the way violence and aggression informs much of Sharits art. Sharits’ was a life surrounded by violence. We learn at the start of the film that Sharits was born, ironically enough, blind, but had his eyesight restored by a doctor on a military base. If this ‘birth story’ were not true perhaps Miron would have invented it, since the event seems like a perfect metaphor for Sharits’ talents as a visual artist: was he was ‘reborn’ with special vision? His mother commits suicide when Sharits is 12 years old. Sharits is stabbed in an alley by a woman and years later is shot in a case of mistaken identity coming out of a NYC bar; his brother Greg tries to commit suicide, fails, then dies by exposing himself to the path of an LA police officer’s gun fire in 1980. And then Sharits commits suicide at age 50. There is enough tragedy and calamity here for several lives.

Frozen Film Strips

Sharits at work

Morin’s style is also unique for a talking head doc in the way he makes excellent and instructive and artistic use of excerpts from Sharits’ films, extant interviews with Sharits, archival footage of his installation works, Sharits’ personal film notes, notations, audio interviews, and creative use of Sharits’ films interlaced with the interview subjects. Miron is clearly in love with his subject but rather than mystifying it he uses words, text, dialogue, split frame, voice-over, and visual aids to help de-mystify Sharits complex working methods, which historian Stuart Liebman tells us required him to begin studying perceptual psychology. Miron, himself a staunch film (i.e. celluloid) guy, still avails himself of the new digital technologies, such as superimposing Sharits’ hand-written work notations over shots of someone explaining the notated film technique. Through his approach Miron manages to explain in fairly clear terms the inner formal dynamics of Sharits techniques (flicker effect, side by side multiple screen film projections, installation pieces, color theories, etc.) and an art practice predicated equally on Sharits’ creativity and the viewer’s perceptual system (the ‘mind’s eye’ and its abilities and inabilities to see, perceive, digest, think, feel). In one illuminating section the interviewers explain the slippery nature of Sharits ‘film of a film’ Sound Strip/Film Strip, 1971-72, which is a film which appears to be showing us a piece of film as it threads through the projector, which of course is an impossibility, hence an illusion of an illusion. In another example, in an audio interview with Sitney, Sharits explains how through the flicker effect technique across frames of varying solid colors, the film “invents” new colors, what Sharits calls “temporal colors” and Sitney ‘synthetic colors’ that do not exist in any single frame but collide together in the mind’s eye. Morin supplements audio segments like this with helpful textual and visual aids or creates meaning through his own montage. As a piece of education Paul Sharits serves as both an introduction to the work of Sharits —and by extension experimental cinema of the 1960s, 1970s— and an enlightening illumination for the more initiated (to experimental cinema) viewer. Paul Sharits is, in the end, a revelatory experience that should not be missed.

Addendum

The wonderful France-based DVD label that specializes in experimental cinema, Re-Voir, has recently released Paul Sharits on DVD. The DVD is an excellent anamorphic (albeit non-High Definition) transfer of the film which comes with in-depth liner notes on the films and art of Paul Sharits by Yann Beauvais. And at 40 pages of small print, with over 50 footnotes, I mean in-depth (the text is actually 20 pages since it comes in English and French versions). Re-Voir also distributes a compilation of director François Miron’s own short films, François Miron: Films experimentaux/Experimental Films 1985-2009.