Pregnant Silences: Waiting in Expectation at Fantasia 2004 and 2005

Miike and Company

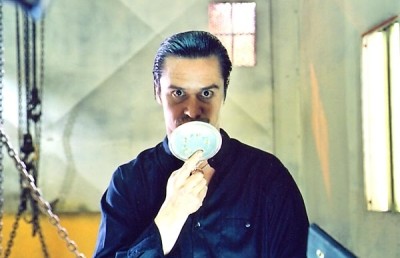

When Takashi Miike’s Deadly Outlaw Rekka (2002) came to Fantasia last year, there was a level of expectation so palpable in the Hall auditorium that I thought people were going to lose their minds. For fans eager to jump into more Ichi the Killer fare, Rekka turned out to be one of Miike’s more frustrating outings. Despite periodic outbursts of heavy action scored with highly charged prog rock from Japan’s Flower Traveling Band, Rekka was deliberately slow. You could hear the tension building in the room as little moments caused isolated outbursts of laughter from one or two people while the rest rustled nervously wondering if this screening was going to deliver or not. 2003 had seen massive walkouts during Miike’s Man in White (2003), another very slow offering – which also happened to be two and a half hours long and which started a half hour late. Not so many walkouts for Rekka, but a really weird energy filled the space until, at long last, Riki Takeuchi donned a shoulder-mounted rocket launcher and started laying waste to various large buildings.

Not quite the finale boasted by Dead or Alive (1999), but enough of a release to turn the evening from an exercise in tantric restraint to good ol’ fashioned climatic release – all the more appropriate for a film which inspired more pregnant silences than I’ve heard in a while.

Thick periods of audience tension are a huge part of the Fantasia experience for me. Certain films get crowds going from start to finish, one of the most astonishing examples of this being last year’s Hall auditorium screening of Calamari Wrestler (Minoru Kawasaki, Japan, 2004).

That ridiculous squid suit had people cheering and screaming for the entire duration of the film, and when the director came out at the end he was greeted with a standing ovation and uproarious applause. That was pure magic, and an example of why you really had to be there to get the most out of that particular film. But the fact that this kind of festival energy exists at Fantasia also means that sometimes it translates into something a little more awkward – but no less compelling. This awkwardness comes when a film is only partially living up to people’s expectations. This is a kind of suspense that can be engineered by a filmmaker, but is often more the result of an imbalance between expectation and result. When a crowd is primed to explode and are forced to restrain themselves, we have a situation like Rekka in which the fun is more in waiting to see what might happen rather than the happening itself. I suppose my enjoyment of this phenomenon comes on the backs of other people’s frustration, but what are you gonna do. Rekka was one of the most potent Fantasia screenings I’ve ever attended, and its precarious balance in a kind of limbo is one of Miike’s emerging trademarks.

Too bad Rekka wasn’t part of the 2005 line-up, for expectations and deliveries were the order of the day as a veritable parade of pregnancy angst films strolled across our screens one after the next. A hard sell for any expectant parents in the audiences, but an interesting indication of the mood apparent in international horror cinema at this mid-point through the first decade of the new millennium.

One of the year’s more anticipated entries was Oxide and Danny Pang’s The Eye 2 (Thailand/Hong Kong, 2004). The film offers an interesting premise: a pregnant woman slowly discovers that her baby is going to be the re-incarnation of her husband’s dead ex-wife. But this isn’t as soapy as it sounds, for it plays off of heavy Buddhist influences regarding relationships between the world in which we live and that which lies beyond. As such there is a very spiritual aspect to the film’s supernaturalism, a combination that might seem obvious but which is so often absent from these kinds of stories. Indeed, the film boasts some genuinely creepy stuff in between more obvious (and rather irritating) audiovisual shock cuts.

Permit me to digress briefly on the subject of abrupt editing techniques. Slamming down a sudden heavy sound effect is a really easy way to scare people into jumping out of their seats, but it is not necessarily a good way to get people scared by the film’s true content. It’s a surface fright that can actually distance the audience from engaging with the film. And when sitting in Concordia’s Hall auditorium, another level of distanciation might be found. Indeed, there are two levels in the theatre. In the lower level, the speakers on the side-walls are well above ear level (as they are in most theatres). But in the upper level, where I prefer to sit due to the gigantic nature of the screen (the largest screen for 35 mm projection in Montreal), these side-wall speakers are at ear level. With the tendency to throw a whole lot of these shock cuts to the surround channels, these intense sound blasts are more than startling. They are terrifyingly loud, and it’s no wonder people get so agitated by them. There is a real visceral quality to this experience that isn’t without its merit, but generally I find it stressful to the point that any moments of suspense in a film which demonstrates its affinity for the use of shock cuts become very pregnant silences indeed.

Much more to my tastes are films that can scare us with sound in ways that aren’t dependent on shock cuts. They use sound to draw us into that which is truly frightening within the audiovisual complex rather than frightening us away from that complex by jolting us out of our senses. One of my favourite examples comes from David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997). In the scene where Fred and Renee are returning home from Andy’s party, Fred enters the house alone to see if anyone might be lurking within. After wandering through the dark for a while, what seems to be a point-of-view shot tracks in on Fred from behind. As he turns around he looks right into the camera, and there is an accompanying orchestration of sounds that begins softly and rises as the camera pushes in.

There is a real tension here for we don’t know how loud the sound is going to get, a feeling that corresponds perfectly with our lack of knowledge concerning the beholder of this visual perspective and whether or not there is actually anyone in the house with Fred at all. The fact that the sound starts quietly and then rises allows us the chance to find our anxiety in the ambiguous relationship between what we hear and see on screen rather than generating anxiety by catching us by surprise with an ultra-tight audiovisual synchronization. This is not an easy thing to pull-off, a fact which clearly suggests why so many horror films take the easier route.

Shock cuts or no, The Eye 2 features some remarkable set pieces which offer a genuine eeriness that made this sequel more interesting to me than the original. The culmination comes with the film’s finale and homage to Polanski’s The Tenant (1976). Unable to cope with the idea of giving birth to her husband’s ex-wife, a woman she despises, our pregnant protagonist tries to end her own life by throwing herself off a tall building…twice. It doesn’t work, a fact which reflects the woman’s status as a being in transition between worlds. Throughout the film she sees the spirits that are to be re-born in the bellies of the women around her. Her ability to see beyond the world of the living suggests that she is on the cusp between that world and the one that lies beyond, and as such death is rendered meaningless and thus impossible. And so she ends up giving birth. The final shot shows a pre-natal class full of pregnant women. We can see spirits standing next to each one, awaiting their new lives.

The Eye 2 resonates with last year’s Miike hit Gozu, a film which finds a mobster dead, only to return (apparently) in the body of a young woman. In the film’s finale, the woman gives birth to the full grown mobster again, and off they go walking down the street arm in arm. Many have compared Gozu with Lynch’s work, including Miike himself who says that the film is something of an homage to the American director. My feeling is that these comparisons are superficial at best. Gozu certainly possesses certain qualities of odd pacing, quirky characters, and double-bass bowing on the soundtrack which do nod to Lynch. But the film’s spirit is far removed from that of any of Lynch’s films in my opinion. Gozu??’s heart lies closer to Von Trier’s ??The Kingdom than anything else, the first cycle of which ends with Udo Kier emerging full grown from the womb of a woman.

Of course you can argue that The Kingdom owes its share of debt to Lynch’s Twin Peaks, but we can play this game of tracing influence up until the point where we just come to realize what so many of my profs have suggested along the course of my education: that Plato was the one truly responsible for anything and everything we’ve ever likely read, seen, heard, or even experienced. I would prefer not to go that route (since it was as tiring during my undergrad days in philosophy as it is now). Suffice it to say that Gozu is more Miike than anything else, and is an interesting piece that I will most certainly be reviewing before commenting further.

Another highly anticipated sequel this year was Ju-On: The Grudge 2 (Takashi Shimizu, 2003). A pregnant actress working on a film about the events that transpired in the original Ju-On story starts experiencing strange things along with the rest of the crew – to the point that she becomes deathly afraid that her unborn child has become haunted. Although more linear than the first film, Ju-On 2 is not without its temporally complex moments. One particularly cool part comes when a man enters his apartment, the camera positioned in another room facing the entry way. We see the man’s girlfriend seated on the floor in the foreground, looking very distraught. She is out of his view save for a portion of her arm protruding into the doorway. Before he can get any closer, he gets a phone call: it’s her, but we can see that she is not on the phone. Now he’s really confused, and enters the room to find her replaced by one of the “others” who comes down from the ceiling and hangs him with her hair. In a later scene, we see the woman enter that same room to find him hanging. She falls back against the wall and sits on the ground in the position that we saw her in before, thus creating a kind of temporal loop.

This is an interesting play on the narrative strategy of allowing the audience to get some information before a character, a very useful tool for creating tension by allowing us to see what is about to befall the person we’re following on screen. Here this is taken to a different level, the foreshadowing turning out to be a play with time rather than just a function of linear narrative. This scene offers a little taste of structural play which lends itself nicely to the story of a woman in transition, about to usher a new life into the world, a life which could well be just the continuation of a life removed from another time and place.

The Eye 2 and Ju-On 2 can, of course, be thought of as representations of the anxieties expectant mothers feel throughout the length of their pregnancies. We’ve all heard the stories of heightened sensory awareness and emotional overloads that are commonplace among pregnant women, and some of you have likely experienced these things first hand. But these are experiences that take place outside the womb. The inside of the womb, on the other hand, is often thought of as a symbol of safety and warmth, a place to which we might like to return in times of distress. Yet as we are reminded in the opening moments of Harry Cleven’s Trouble (2005, Belgium), the womb can be a place of intense struggle…when twins are involved. The film explains that twins often fight each other in the womb until one actually dies, leaving the victor to subsume the sibling, one physically becoming part of the other. Trouble takes this idea as a premise for expanding such sibling rivalry beyond the womb, and offers a finely crafted tale of estranged twins who come back into each other’s lives only to have one undone by the other, fulfilling what might have once been in the womb.

It is the idea of subsuming that is most interesting here. Unlike other twins films in which an attachment between siblings ensures their mutual downfall (ie. Dead Ringers, David Cronenberg, 1988), Trouble posits a scenario whereby long lost Matyas re-enters the life of his twin brother Thomas in order to take it over. It starts with Matyas winning over the hearts of his pregnant wife Claire and son Pierre. It may sound at bit implausible that a woman would so quickly give up the man she’s built a family with in favour of his brother, but the film’s great strength is how compellingly it manages to illustrate the process whereby twins can so easily stand in for one another – and how easily they can turn against one another.

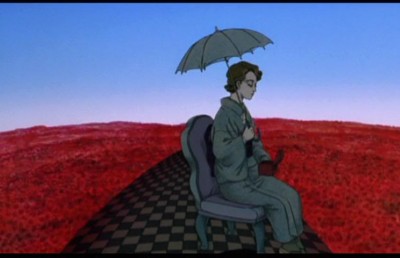

Aesthetically the film is top notch, and casts an audiovisual tone which is conducive to the idea that what we are witnessing may, in fact, be an adult’s imagination of what such a struggle might have been like inside the womb. The feeling of being inside the womb is fostered largely through the film’s soundtrack. In the opening titles there are credits for not only “score” and “sound engineer” but also “musique acousmatique.” The differentiation between traditional score and musique acousmatique, along with a separate distinction for non-musical elements of the film’s sound design, demonstrates an unusual commitment to using sound as a principal element of the film. For those familiar with traditions in electroacoustic music and musique concrète, the idea of acousmatic music comes with the idea of abstraction: hearing sounds for which there is no known source. The idea of not knowing where a sound comes from has clear affinities to the experience of the womb. We know that an infant can hear while inside the womb. It is just as sure that they cannot see and have no experience of the outside world to make connections between sound and source (at least not in the Western context of this Belgian production). The experience of hearing within the womb could thus be considered purely acousmatic. Even more importantly, acousmatic sound invokes the idea that a sound has become so separated from its source that it becomes something else entirely, no longer bound to its original context. The goal of many acousmatic music compositions is to foster just such a break from context so that the listener might be free to experience sound for its own sake. Unlike R. Murray Schafer’s concept of schizophonia, in which there are extreme negative connotations associated with a sound becoming completely displaced from its original context, the idea of acousmatic sound is more positive, an experience of abstraction which might help us remember what it was like to know the world before knowing it. In the case of Trouble I think both ideas are relevant, for ultimately Matyas’s goal is to take the place of his sibling, to displace himself from his original context and ground himself in a new one…for better or for worse.

In one of the film’s more disturbing moments, Claire decides that she is no longer comfortable with the idea that her husband Thomas will be present at the birth of their second child. She arranges it so that Matyas is there instead. The importance of being present at the birth of one’s own child is a crucial concept when considering the film’s theme of context displacement. It is in the moments when a man can witness the emergence of his child into the world that the child’s origins are sealed in his mind. Claire’s decision to replace Thomas with Matyas as witness to the birth is a compelling illustration of the process by which she intends to substitute one context for another. Yet whether or not Matyas finally succeeds in replacing Thomas is a tad ambiguous. The film’s final moments offer a complex scenario indeed. There is a prolonged battle between the two brothers during which they become increasingly confused. By the end of it we do not know who has emerged the victor. The film ends with a scene in the park where Claire and the children are greeted by a man she believes to be Matyas. Not only is it horrific enough that she has replaced Thomas with Matyas in her mind, but then we realize that the man may, in fact, be Thomas impersonating Matyas. Think of the horror whereby a man whose brother has stolen the affections of his wife must then live out his days impersonating the brother in order to remain in the family that he loves. This is trouble indeed. A great film all around.

When thinking about Trouble I can’t help but remember last year’s Doppelganger from Kiyoshi Kurosawa. Doppelganger is very different in tone from the Belgian film, but a remarkable achievement in its own right. Here there is a supernatural element to the story: the doubling is not the result of a long lost twin re-entering his sibling’s life but is rather an evil double that has emerged from his psyche to fulfill those aspects of his desire that he cannot.

Doppelganger is easily one of Kurosawa’s more refined films, and that’s saying a lot when talking about the director of Cure and Charisma (among many others). One of the great aspects of the film is the use of an interesting split-screen technique in various sections to illustrate the disorientation that comes when one is increasingly exposed to one’s own double. Where the feeling of de-contextualization in Trouble comes largely through the use of acousmatic sound, Doppelganger shuffles its visual space around like a Rubik’s Cube to similar effect.

One particularly good example of this comes when the main character, Hayasaki, comes home to find his double waiting for him in the living room. He refrains from looking directly at him but carries on a conversation as he moves about the space. The screen splits into three sections which gradually emphasize the increasing psychological separation of the two men. The triptych begins simply by breaking a single shot of a hallway into three parts across which Hayasaki moves. He enters the kitchen, and as he does so the left panel shows him moving into place while the other two remain fixed on the previous location. Hayasaki’s double now moves down the hallway in the same direction. The triptych then changes to represent the space which houses the bedroom in the foreground and kitchen in the background. Hayasaki is standing in the kitchen as the double makes himself comfortable on the bed. They then continue their conversation, the right panel now giving us a close-up on Hayasaki’s face while the other two panels remain as before. Here the orientation of the two men with respect to one another is in tact: the right panel shows Hayasaki turning his head in the direction that we find his double on screen, so there is a logic to their on-screen relationship. As the scene progresses, however, Kurosawa shifts Hayasaki’s position from the right panel to the left with a moment in the middle where Hayasaki is shown on either side of the triptych while the double remains in the middle. This shifting then culminates with a disorienting moment when Hayasaki gets frustrated and yells at his double to which the double responds by looking in his direction: screen right. Their orientation in the real space of the house has not changed, but their orientation on screen has. Hayasaki now occupies the panel on screen left, and so the two have been drawn apart.

So the formal aspects of the split screen reflect Hayasaki’s feelings of separation from his doppelganger, and perhaps ultimately his separation from himself. When we consider the film’s premise that doppelgangers appear to people just before they die, we could understand Hayasaki’s process of disorientation as a transition between worlds. This transition is reflected in the ways that Hayasaki and his double make the transitions between the panels of the triptychs. In this way Kurosawa has fashioned a marriage of form and content that I find very satisfying.

Fruit Chan’s “Dumplings,” the first part of this year’s Three…Extremes, offers yet another glimpse into the struggles of transition between the womb and the world outside. While we don’t find twin siblings trying to consume one another, we do find consumption of another kind and, as always, the unborn do live and die in the bellies of women. Only here the main belly under consideration is that of a distraught middle-aged woman in search of the fountain of youth. Her version of the fountain comes in the form of a naturopath famous for her age-reversing dumplings. The secret ingredient? Ground-up fetus. Perhaps a commentary on the ethics of stem-cell research, “Dumplings” is more likely a simple exploration of the belief that you are what you eat.

Rest assured, however, that the film is well beyond the vulgarities that its subject matter might seem to necessitate. It features sumptuous cinematography by Christopher Doyle, for one, and it progresses at a very measured pace (which I’m told is expanded even further for the film’s feature-length release). It is with this measured pace that the audience is allowed time to reflect on the unstated ethical issues inherent in the consumption of one life to further another. It would be all too easy to say that this is simply the way life works. Even vegetarians consume life to further their own, and we’re all aware that life consumes life as part of the organic cycle to which we are all bound. Instead, this film offers a portrait of a psyche tormented by a society obsessed with youth, where people of every age consume the idea of youth on a daily basis. In Dumplings, the idea of consuming youth is taken to its logical extreme.

More than this, however, Dumplings offers another angle to the idea of family members trying to replace themselves. When our hero discovers that she is herself pregnant and then loses the baby in miscarriage, you can guess what happens. Gruesome, yes. But philosophically no more uncommon than the idea of parents trying to enjoy a second youth through their children. So we are left with the question: is the quest to rediscover youth a noble one? Is it a quest that should be embarked upon by any means necessary? If there are limits to the lengths we can ethically go in pursuit of a second childhood, then what do they tell us about the legitimacy of this pursuit? These are questions. The film offers no answers.

Maybe the best way to understand Dumplings is as an allegory for anxieties surrounding the generation gap between middle-aged women and their children. This is certainly the way to understand my favourite of this year’s festival: Tetsuo Shinohara’s Karaoke Terror (2004). The film’s premise is that a late-30s woman is murdered by a teenager after his attempts at seduction fail. “It’s usually so easy to get you older women wet,” he says while accompanying her through the rain against her will. When her soaked body is discovered in the mud by a friend a few hours later, she and some companions decide to wage war against the younger generation. They find the one responsible for the woman’s death and kill him. Then that guy’s friends return in kind, and so it alternates for much of the film until things get a little out of hand. The women eventually get the chance to take down almost the whole clan in one go when they let loose a rocket launcher after coming upon the group perform a song and dance number in drag on a deserted pier. The single survivor then retaliates in a way that is sure to succeed: by dropping a nuclear bomb from a rented helicopter over the neighborhood where the women live. The film ends as the mushroom cloud rises and it becomes clear that he is on his way down with everybody else.

Based on my description of its narrative escalation, it may seem as though the film is a bit silly. But it is actually deadly serious…and pretty damn funny too. Shinohara manages to balance dark humour with an emotional content that really puts its finger on the humiliation that can exist across the gulf of teenage males and thirty-something females. Typically, youth-oriented societies foster a pattern of older men sleeping with younger women. Very few films have ever reversed this dynamic; Harold and Maude (Hal Ashby, 1972) still being the one to beat. So it is from this standpoint that Karaoke Terror develops some of its more rewarding aspects. These women are still very young in comparison to Maude, and yet from the perspective of the teen boys they are pretty much over the hill. But there is a delicate balance at the hill’s cusp, and one poignant scene involves one of the women becoming seduced by a boy at a nightclub. She goes as far as removing her blouse in the washroom as he kisses her, but there it stops. He notices something about her undergarments which suggests to him that she wasn’t really equipped to go all the way, and tells her that she shouldn’t be putting on the façade of a sexual being if her insides aren’t prepared to follow through. He walks out on her and she is left in the men’s washroom semi-dressed and completely humiliated.

There is nothing funny or grotesque about this scene. It is genuinely upsetting, and recalls the emotional intensity of a similar scene in John Cassavetes’ Faces (1968) where a group of middle-aged women take a young man home from the bar. They start dancing in the living room, and the man entices one woman to join him despite her initial refusals. It was clear that it would take a lot for her to let go and find the spirit of her younger days, and when she finally manages to get up the nerve he shuts her down. She is left standing in the spotlight alone, and ends up leaving in a state of debasement.

It is moments like this which makes Cassavetes so overwhelmingly powerful, and Karaoke Terror taps into this quality while simultaneously managing to offer enough blood and apocalypse to suit most Fantasia veterans. A remarkable achievement which expands upon the theme of anxieties between parents and children (unborn or otherwise) so rampant in the last two editions of the festival.

Finally, “generational conflict” could be a good subtitle for this year’s lone feature length Miike film: Izo, a somewhat bizarre outing in which a violent warrior travels across generations to exact his revenge on those that killed him so long ago. Doesn’t make sense? Doesn’t matter. This is a film which takes the inextricable link between birth and death so much for granted that it presents Izo as a constant across both planes, dolling out death as he is constantly reborn. The film isn’t really like anything I’ve seen from Miike before. The violence is not that of Yakuza warfare, nor of noble Samurai battle. It’s almost inexplicable in its constancy; it seems to be the film’s sole reason for being, despite musical interludes from folk singer/guitarist Kazuki Tomokawa (somewhat reminiscent of The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (Wes Anderson, 2004). Izo presents a world in which everyone fears the coming of the warrior, but in which the warrior himself embodies the reason why such fear is unnecessary. Nobody can escape death. And from this film’s perspective, it would seem that nobody can escape rebirth either. I’m not sure if I enjoyed the experience, and I’m a rather dedicated Miike fan. But for those interested in his work I suggest that this one is required viewing. I’m glad I fulfilled the requirement in the context of its Hall auditorium screening. Like last year’s Rekka there were pregnant silences aplenty; I dare say the audience didn’t know what to make of this one. The highlight moment of my festival came when, upon the completion of Kazuki Tomokawa’s longest number there was a beautiful pause in which an audience member behind me was heard to exclaim “Un autre!” That’s my general feeling towards Miike: you keep makin’ ‘em and I’ll keep watchin’ ‘em. And I trust that Fantasia will keep bookin’ ‘em to ensure that we can all watch them in the best environment possible.