Ideology and Social Commentary in Le Couperet

Costa–Gavras’ Political Black Comedy

The autumn of 2005 marked the re-appearance of a grand auteur. Costa–Gavras managed, at the age 72, to make one of those rare films that lingers in one’s memory long after having left the theatre. Costa–Gavras looks anew at a social and political issue with such a fresh eye that it is hard to believe he completed such a project at the beginning of the eighth decade of his life.

It is not, of course, the first time Costa–Gavras rocks the film industry by presenting the ugly truth only a brave few are willing to admit. Oscar Wilde used to say that the truth is rarely pure and never simple and indeed, the Greek-born director of mainly political and polemical films, such as State of Siege (1973), Missing (1982), Z (1968), and Mad City (1997), was never afraid to speak about controversial issues, using his camera, his background and his acute intelligence as an alternative weapon with which to display a tormented society.

However, this essay does not intend to present Costa–Gavras’ career or biography. This has been done quite well by many others. The target of our essay is an attempt [1] to unravel the intricate levels of sociopolitical meanings within Le Couperet, an “_Ax_” [2] that takes whatever form or shape one desires and is used as a weapon in an increasingly callous society.

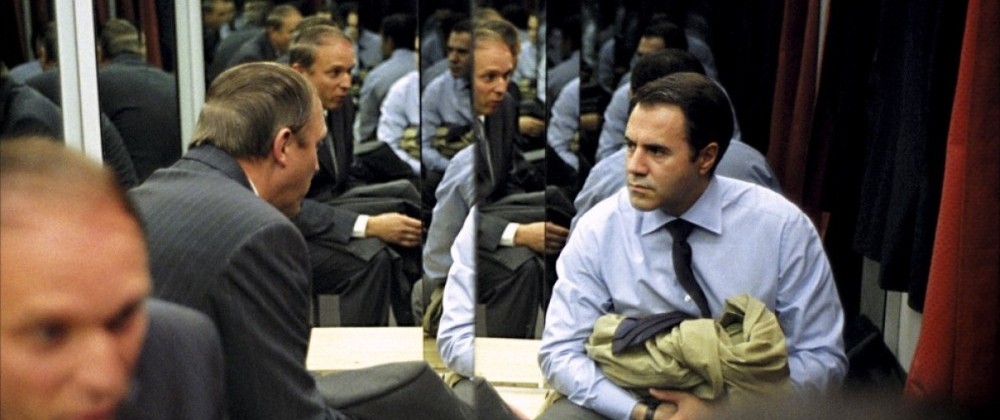

The story of this “morbid tale of the everyday inhumanity” [3] is quite simple. The hero, and we use the word in its broadest sense, Bruno Davert (exceptionally portrayed by José Garcia) has been unemployed for 2 ½ years. Bruno is frustrated, sad, and anxious, with a ten-year mortgage, two adolescent children and a wife who helps make ends meet with part-time jobs as a cinema cashier and a nurse. Bruno comes up with an impossible idea: eliminate the competition who stand in his way and he will finally land his dream job. So he digs up a relic of a gun, a family heirloom from his father’s struggle in WW II, and with the CVs of the five people on hand, he starts killing the men he considers his prime competitors for a coveted post in the paper industry.

Signs and Symbols in the Service of the Narrative

Costa–Gavras opts to start the film at the time of the third elimination and then show in a forty-minute flashback how things have gotten to this point. The opening sequence has Bruno in his car waiting for his unsuspected victim to leave a café-bar. The night has fallen and Bruno seems quite on edge. The name of the establishment flashes and we distinguish the sign which says étape. The symbolic use of signs commences from the outset of the film. The word étape is not used inadvertently; its first meaning in French defines the place where troops in both World Wars would rest for the night. If we combine the name of the place with the weapon that Bruno is holding (a luger pistol from World War II), we immediately conceive the director’s first social comment: Our precious modern society is in a state of war. Danger lurks behind the carefully manicured bushes and freshly mown lawns covering nice little suburban homes, where fatigued, unemployed middle-aged men spend hours perfecting their résumés and waking up at the crack of dawn to check their mail, in the hope of a positive reply or an appointment for a job interview.

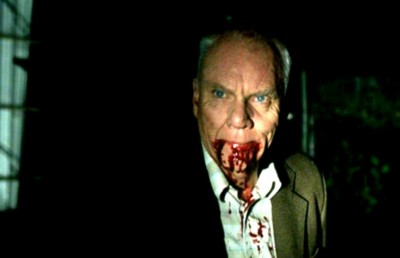

Bruno finally commits the murder and retreats to a motel room, where he shakes uncontrollably in disgust at having committed another atrocious act. Tormented by guilt, he proceeds to record his confession using a digital device which was presented to him at work as a token of the company’s appreciation for fifteen years of hard work. An inserted scene reveals Bruno amongst his colleagues and boss, taking pride in being the center of attention and being acknowledged by his peers. Costa–Gavras adopts a series of objective [4] shots, while the camera remains at a distance, as if an extra-diegetic narrator [5] were presenting the facts, but allows the audience to reach their own conclusion. In addition, this scene stands in stark contrast to the previous one, as Bruno has been transformed from a productive, satisfied individual to a serial killer, and not because of some mental disorder but by choice.

Bruno’s voice-over informs us that six months after the above work ceremony, six hundred employees were made redundant due to the relocation of the company. He was one of them. Bruno shares a scene with his boss in the midst of a rally that is taking place outside the company’s headquarters, while the camera follows a sign written by the protesters visible through the window: We wish death to those who have given it to us. Costa–Gavras openly accuses the corporations who have taken control of people’s lives and are responsible for the nouveaux-pauvres of the western world. However, his hero still has a chance, since he leaves the company with excellent references and a severance package.

The voice-over continues, along with a cut which transports us two and a half years later. Bruno is attentively placing cover letters and CVs into envelopes, while his wife is trying to be of assistance, something that Bruno does not find helpful. I had become aggressive and anti-social, he observes, as if his job was the only thing that characterized him and gave him a sense of being. Having located the competition through a post-office ruse, he deduces the numerous candidates whom he considers at least as experienced and as eligible as himself to five men. Bruno comes to the decision to kill these men through inference: if he kills the greedy shareholders, nothing will change; if he goes after the ten managers, thousands may lose their jobs. Hence the only thing that stands between him and his dream job is the five CVs. His mind is made up. Bruno gets his father’s weapon and drives to Belgium to kill his first victim. He arrives just before the postman and when the victim responds to his name, Bruno shoots him and drives away. Bruno does not wear a disguise, nor does he drive a rented car. He is just wearing a fishing hat and a pair of myopic glasses. As he drives away a smile appears on his face, the smile of a naughty child who has just committed a mischievous act. [6] A sudden cut brings us back to the hotel room where an anxious Bruno records his confession: I zapped him and that drives me mad, we hear in voice-over; another cut brings us back in time and shows the termination of the second CV.

Throughout the film, Costa–Gavras deploys his accomplished cinematic technique to carefully build up a type of Hitchcockian suspense, while still immersing the plot in social commentary. He uses dialogue only when necessary, preferring to manipulate the visual medium to make his social statements. A number of symbols are brought into play which assist this strategy. Throughout the film Bruno passes by billboards which advertise mainly women’s products, signs of the incessant production of material goods that encircles the hero and his environment, and which makes everyone a victim of consumerism. Costa–Gavras explains that:

The advertisements are linked to the character. I didn’t put them just to make an anti-publicity comment. The character, just as the majority of people, is surrounded by these advertisements that propose very beautiful things that stimulate him. But he can no longer afford what is being advertised. That’s a big frustration. That participates also in the loss of his self-esteem.7

However, the placing of these advertisements in the film goes beyond their employment as a fervent statement against consumerism; a number of compelling connotations can be derived from a close analysis of them. The first billboard we see is in the first sequence, while Bruno is following his enemy in his car, and presents a woman’s hand forming a fist showing three oversized rings with precious stones, which hints obliquely at an iron device used as a means to inflict injury.

The second billboard is situated outside the motel where he takes refuge in the opening sequence, after the third murder. The large poster presents a woman’s hand holding an expensive watch. What is intriguing, however, is that the hand is holding the watch in the same way a murderer would hold a knife. In a sense, the watch becomes an important sign (in the Saussurian sense), a weapon of power and status: a symbol of what really matters in today’s world. Another possible connotation is that Costa–Gavras is paying tribute to Hitchcock with the photo still by indirectly referring to the celebrated shower scene in Psycho.

In the third billboard located before a gas station, a mobile phone company advertises its latest model by placing its product inside a pair of sensual women’s panties. A mobile phone is not just a practical tool, but a highly sophisticated instrument that defines its owner in terms of wealth and prestige. The position of the mobile phone in the billboard bears a strong resemblance to the way cowboys wore their pistols in westerns. Once again, a seemingly innocent advertisement is converted into a potentially violent image of modern times. As the plot progresses, a number of other billboards appear, such as a poster of a woman wearing dark glasses, alluding to the secret that Bruno is concealing; and a poster showing just a woman’s body in expensive lingerie, hinting at the unknown territory the protagonist is exploring. Rather than depending on dialogue, these perceptive shots of posters comment on aspects of social decadence by foregrounding the visual and dialectical aspects of cinema.

Shaking the Dominant Tower of Ideology

In Marxist theory, ideology is the discourse that gives society its meaning. However, ideology remains the privilege of the ruling classes and as such it becomes “the practice of reproducing social relations of inequality. The ruling classes not only rule, they rule as thinkers and producers of ideas and so control the way the nation perceives itself…” (Susan Hayward, 2000: 193). On the other hand, as Hayward points out, “while ideology is dominant… it is also contradictory, therefore fragmented, inconsistent and incoherent. Moreover it is constantly challenged by resistances from those it purports to govern” (2000: 194). Many mainstream films uphold ideology by presenting a series of moving images that provoke what Christian Metz [1968: 14] calls an indelible impression of reality, an ‘illusion’ of realism constructed by the cinematic apparatus which appears almost impossible to question.8 Nevertheless, as there are groups of individuals that defy the ideological norms of their nations, there are filmic texts which dare to rock the ideological foundations of western societies.

We can easily place Costa–Gavras in the list of those rare auteurs who not only push their visual medium to its limits, but have the courage to imbue their films with elements which redirect, redefine or simply call the basic ideological norms into question. In Le Couperet, Costa–Gavras firstly questions the foundations of the well-oiled machine we call western civilization. Should a person be defined by his/her work? Should s/he be defined by his material possessions? Is globalisation the best way to go? Throughout the film, Bruno remarks on the unpleasant situation he is in because of the decisions of the companies to relocate and dismiss members of their staff in order to increase their already healthy bank accounts. Still, Bruno is not alone. His five victims and thousands others are in the same sinking boat. Having devoted most of their productive years to a firm, they finally come face to face with the inhumane corporation, a heartless construction aimed at eliminating people with a view to increasing revenue.

Bruno becomes a serial killer, but by no means is he a demented one. He merely adopts a singular strategy to return to his previous state, to become once again ideologically and politically ‘correct’. Costa–Gavras lets his character commit murders dividing his filmic time between Bruno’s point of view and an extra-diegetic narrator’s detached point of view/position. By dichotomizing the filmic text’s narrative point of view, Costa–Gavras achieves the following: Firstly, he accuses the prevailing ideology which worships money and sacrifices human beings on its economic altar; Secondly, his concerns, fears and anxieties concerning the future of the civilized west are channeled through Bruno’s own words, feelings and actions. In the process, he finally reminds us that the end of cinema, as predicted by Godard, Greenaway, and others, is far from taking place.

Le Couperet (2005) Constantin Costa–Gavras, director

Production Companies: RTBF, Wanda Vision.

Script: Jean-Claude Grumberg based on the novel The Ax by Donald Westlake.

Cast: José Garcia (Bruno Davert), Karine Viard (Marlène Davert), Geordy Monfils (Maxime Davert), Christa Theret (Betty Davert), Olivier Gourmet (Raymond Mâchefer), Ulrich Tukur (Gerard Hutchinson). Duration: 122 min.

Endnotes

1 We use the terms “essay” and “attempt” in the way Robin Wood understands them. Wood (1998:8) writes: “… I like the term essay for its derivation from the French essayer: to attempt: its chapter is, precisely, an attempt, and, as we know from T. S. Eliot, ‘Every attempt is a new beginning / And a different kind of failure.”

2 The film is based on the novel by Donald Westlake entitled The Ax.

4 According to Francesco Casetti (1998: 17-20), there are four kinds of shots: 1) objective shots 2) shots where the character looks at the camera 3) subjective shots that identify the eyes of the spectator with those of the fictional character, and 4) fantastic objective shots, that have been filmed from strange camera angles and identify the eyes of the spectator with the camera lens.

5 In his influential work, Figures III, Gérard Genette (1972) distinguishes the different types of narrators from which we will present the main three categories: 1) The extradiegetic narrator (narrateur extradiégétique): the narrator who is placed outside the story they narrate, whose identity is usually unknown, 2) The intradiegetic narrator (narrateur intradiégétique): the narrator who participates in the story, and 3) The metadiegetic narrator (narrateur metadiégétique), the narrator who narrates a new story inside the main story. Genette’s theories were first applied to literary texts, but contemporary film theorists such as Robert Stam (1992) and André Gardiers (1993) have found that the same categories can also be applied to the filmic text.

6 We should underline the impeccable performance of José Garcia, which reminds us of a young Jack Lemmon, that is an actor with an every day face but capable of delivering the subtlest nuances of even the most hideous emotions mixed with satire, irony and humour, in such a way that he does not lead the audience towards an a priori rejection of his actions.

7 “Le Couperet: notre rencontre avec Costa Gavras…”. Gavras, Costa. Interview with Reynald Dal Barco. March 2nd 2005. March 6th 2006.

8 The collective authors of New Vocabularies in Film Semiotics, Robert Stam, Robert Burgoyne, and Sandy Flitterman-Lewis (London, New York: Routledge, 1992), explain the “impression of reality” as follows: “Film semioticians spoke of the Impression of Reality engendered by the cinema, triggered by a) the perspectival analogy of the photographic image, b) persistence of vision and c) the Phi-Effect or “phenomenon of apparent movement,” i.e. the perceptual-cognitive mechnism by which the mind posits continuities of movement even when perceiving, as in the cinema, nothing more than a series of static images” (p. 187).

Bibliography

Casetti, Francesco. Inside the Gaze. translated by Nell Andrew with Charles O’Brien ; preface to the English edition by Dudley Andrew, introd. by Christian Metz. Indiana University Press, 1998.

Gardies, André. Le récit filmique. Paris: Hachette, 1993.

Genette, Gérard. Figures III. Paris: Seuil, 1972.

Hayward, Susan. Cinema Studies. The Key Concepts. USA: Routledge, 2000.

Metz, Christian. Essais sur la signification du cinéma. Paris: Klincksieck, 1968.

Stam, Robert. New Vocabularies in Film Semiotics. London: Routledge, 1992.

Wood, Robin. Sexual Politics & Narrative Film. New York: Columbia University Press,

1998.