L’Âge des images

The Video Work of Jean Pierre Lefebvre

Depuis trente ans, je répète cette chose si simple et si inquiétante à la fois: le cinéma québécois est l’image même du Québec, et le Québec l’image du cinéma québécois. (1988) [1]

For thirty years now I have been saying something that is simple and disquieting at the same time: Québécois cinema is a reflection of Québec itself, and Québec a reflection of Québécois cinema.

With over twenty features to his credit, Jean Pierre Lefebvre is unique in québécois cinema. He neither began in documentary nor, except for two short periods, did he ever work at the National Film Board. Instead he began as a commentator on the emerging cinema in Quebec—a practice he continues today. His many articles for Objectif, Cinéma Québec and more recently for 24 Images argue his belief in a truly national cinema—a cinema unique to a particular place and time.

Furthermore, Lefebvre has taken pride in making his films as inexpensively as possible. Although spectators may find an ascetic dimension in this attitude, the reasons have also been economic and political. But as filmmaking in Quebec has become more expensive, Lefebvre has been pushed to one side. After the critical failure of Le fabuleux voyage de l’Ange (1990), Lefebvre turned to video—a medium he had been using for some time now in the production workshops that he had been conducting up and down the country.

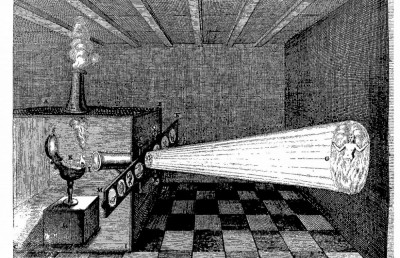

Somewhat like Godard’s eight-part video essay, Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998), Lefebvre’s five-part “L’Âge des Images” (1993-1995) addresses the failure of cinema to sustain its early promise—Godard in terms of the high culture of nineteenth-century aesthetics; Lefebvre in terms of the social caring that characterized the early cinema of Quebec. [2]

Consisting of four 50-minute essays and one fictional feature, “L’Âge des Images” examines the construction of video signs. Although each is a separate entity, collectively they speak across one another like the serial panels of a religious pentaptych.

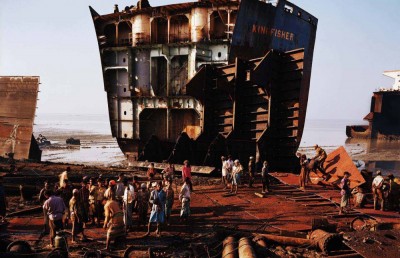

The first, Le Pornolithique, presents the violence endemic to television representations, whether actual or fictional. Brutal images are punctuated by the recurring image of Samuel, Lefebvre’s baby son at that time. When, towards the end, his eyes look up at us, the effect is electric. What kind of world is this child growing up in? What will his eyes be obliged to see?

L’Écran invisible is the most experimental of the essays. Contrasting past images of fullness with present images of emptiness, it is as delicately suggestive as anything Lefebvre has done. This essay is about potential—of friendships, of family relationships or, quite simply, of a chair waiting to be filled by the shadow of the filmmaker. Unlike Le Pornolitique with its explicitly violent images, L’Écran invisible is full of images rich in suggestiveness. It is up to the spectators to fill them with meaning.

Comment filmer Dieu?, as its title implies, is both serious and playful. Lefebvre walks about the streets of Toronto, talking to us, the spectators, and to Lionel Simmons, his cameraman, about the denaturing of nature. Forest glades are recreated inside hotels while actual lions are encaged in zoos. We have created a world, Lefebvre explains, “capable de rendre la réalité semblable au rêve et le rêve semblable à la réalité” [capable of making reality look like a dream and dream look like reality]. Yet within the noise of the city, a low-budget film is being made. As always with Lefebvre, he is concerned with the survival of alternatives over time, with truly nurturing cultures. In this film, this seems to refer to those cultures that acknowledge time, that take the time “to film people believing in people, people believing in themselves,” as the director of the low-budget feature explains in English. This statement provides a moral, not only for the video but for all of Lefebvre.

Mon chien n’est pas mort, while supposedly a film about a mongrel pup recently acquired for Lefebvre’s children, is actually about the creative imagination at its most defensive. It examines how a filmmaker functions when denied access to the tools of his trade. Effectively, he makes a home movie. Yet all the time he is reflecting both on his family life and on the ideas that have influenced him.

Citing many authors, he ends with Fernand Pouillon who, in Le Pierres sauvages, declares: “La réalité est banale en dehors du plaisir de la faire naître” [Reality is banal outside of the pleasure of creating it]. It is the game of observing life, the act of recreating its exactitude, that endows it with significance. This is the game that has been played in all of Lefebvre’s work and which will be given dramatic form in the video feature that ends this series.

La Passion de l’innocence

Ce que j’ai continué à réclamer et à appliquer dans mes films … c’est le droit à la petitesse, le droit de continuer à faire des films qui ne prétendent pas au chef-d’œuvre absolu. C’est le droit de continuer à chercher dans une œuvre qui est d’abord et avant tout une mouvance, une réflexion. Je réclame le droit de faire du cinéma primitif. (1990) [3]

That which I continue to claim and apply in my films…..is the right to modesty, the right to continue making films which do not pretend to be absolute masterpieces. The right to continue searching, in a work which is first and foremost a movement, a reflection. I reclaim the right to make primitive cinema.

The four video essays explore the process of image production. From the pornography of television to the banality of a home movie, Lefebvre invites us to consider the signs that are among us. With the exception of L’Écran invisible, the elusiveness of which lends that study the connotations of fiction, these essays are investigations. They are visual disquisitions upon the images which are part of contemporary urban consciousness.

In La Passion de l’innocence, however, Lefebvre is less investigating than presenting. With extraordinary delicacy, he is creating images that refer to other images, planes of reality that merge with other planes of reality. A simple film, it is a video-film about a wished-for film. Since both the video-film and the wished-for film have the same title, distinctions between them are difficult to discern. As in L’Écran invisible, the meaning of the film becomes the meaning we create for ourselves in the process of experiencing it.

The story is commonplace—an everyday tale about an everyday woman who works as a waitress but wants to be an actress. She hopes to be cast in a film called La Passion de l’innocence. As portrayed by Liane Simard, Michèle is a woman uncertain of herself who longs to play Marjo who is more self-assured. The video-film begins with a screen test, with Michèle garishly lit and awkwardly posed against a wall, exchanging lines with the man who will play Paul (Widemir Normil), her black lover in the wished-for film.

This is how the industry works, Lefebvre is suggesting, because Lefebvre would never treat his cast in so impersonal a manner. A drive into Montreal moves from night to day and recapitulates on the radio-news the violent world of Le Pornolithique. As we move up an empty stairway to Michèle’s second-story apartment, watching her waking up in the morning and feeding her cat, we flash back to different stages of the screen test which in turn flash us forward to different moments in the wished-for film.

These temporal dislocations destabilize our sense of time and tease us by confounding different planes of cinematic representation, perhaps suggesting, as in Mon chien n’est pas mort, that imaginative transformations are as important as reality itself.

As in all of Lefebvre’s work, this video-film is full of longueurs. We see Michèle alone in her apartment. Although she says nothing, she is always reacting—sometimes to something said, as when she listens to her lover’s tape, but generally just to her own thoughts. Lefebvre passes on to us the responsibility of imagining what these thoughts might be.

A pure example of this stylistic strategy occurs with Pauline (Geneviève Langlois), Michèle’s sister, travelling on the métro. When we first see her, we don’t know who she is. And yet, as we look at her looking at nothing in particular, her expression passes from a look of distress, through the gradual broadening of a smile into quiet laughter, perhaps from a story remembered or from an inner reconciliation with some grief. When other people enter the carriage, her expression returns to neutral—to being alive in the world on a train.

When we later learn that she is HIV positive, we may feel we have gained a retrospective understanding. But not necessarily. Furthermore, in its passage from anxiety to acceptance, Pauline’s scene in the métro encapsulates the emotional trajectory that Michèle will follow throughout the course of the video-film.

Both sisters have a conflicted relationship with their mother, the conflict always taking place on the telephone. The mother never appears. Nor does Renaud, Michèle’s chum in Calgary. The repeated separation of sound from image restores to this video the magical evocations of silent cinema, of the joy simply of observing what is there.

The love scenes in the wished-for film, all shot in wide-screen black-&-white, are delicately handled. Her white fingers intertwined with his black ones, his wedding band on display, convey the intimacy that they feel for one another as well as the reasons why the relationship will not continue. He cannot leave his wife.

Another extraordinary scene involves an orange, a phone call, and Carnaval, the cat who, according to the credits, helped write this film. While Michèle is eating an orange, spitting out the pits, a phone call informs her that she didn’t get the part, somewhat contesting the “reality” of the wished-for film that we ourselves have been “really” experiencing. She continues with her orange, piling the rinds on the antenna of her cordless phone before flipping them on the floor for Carnaval to play with.

Such a scene recalls that celebrated moment in Vittorio de Sica’s Umberto D (1952) when the maid gets up in the morning, grinds the coffee, and gets ready for the day, while a cat walks along the glazed roof above her head. Although such scenes have nothing to do with the plot, they have everything to do with the world in which the plot is taking place.

So it is in the films of Jean Pierre Lefebvre. None of these moments in La Passion de l’innocence have anything to do with the plot largely because, outside the wished-for film, there isn’t one! The temporal dislocations, the shifting planes of reality, those wonderful speechless moments of sustained reaction uncouple this film from any narrative dependence on cause and effect. A cinema of action has become a cinema of contemplation.

The end of the film seems like a tribute to Gilles Groulx, to the memory of whom Lefebvre had dedicated Le Pornolithique. As in the penultimate scene of Le Chat dans le sac when Barbara (Ulrich) is putting on her make-up and talking to herself in the mirror, in the penultimate scene of La Passion de l’innocence, Michèle too is talking to herself in the mirror, but her reflection is Marjo—the character she has wanted to be. When Michèle asks permission to wear Marjo’s clothes, Marjo assures her that she can borrow her character as well. If Michèle has the ability to imagine the character, she can become that character. Michèle’s mirror reflection explains:

C’est toi qui décide. C’est toi qui décide que tu as la force d’aimer qui tu veux, que tu as la force d’être qui tu veux, que tu as la force de plonger.

You are the one who decides. You are the one who has the force to love who you want, to be who you want, who has the strength to take the plunge.

Empowered to achieve the strength of the character she wanted to play in the wished-for film, she sets off for the site of her scenes with Paul, her imaginary lover in the wished-for film. Now the winding staircase is full as we follow her down it; and now these sites that we have seen before in her black-&-white world are in colour.

She returns to the amphitheatre in the Parc le Provost where she had enacted (or imagined) her scenes with Paul. She stands in the centre as the camera circles around her, as it had circled around the departing lovers in the wished-for film. But instead of an imagined grief, she now experiences acceptance. When she sits on the bench, we experience the same play of emotions we had witnessed with Pauline in the métro. Her face moves from thoughtfulness into a broad smile of self-acceptance, now freed from fear.

The final titles are intercut with more scenes from the opening screen test, as if to remind us that we have just participated in an intricate game of cinematic representation. Narratively, the film ends where it began.

The films of Jean Pierre Lefebvre are all, finally, a philosophical disquisition on the ultimate value of life and on what it means to be Québécois in the 21st century. His video series has allowed him to return to the direct simplicity with which he began with L’Homoman in 1964. As he explains in Mon chien n’est pas mort about working with video, “Ça nous permet de jouer des images comme, comme Félix et Brassens jouaient de la guitare” [It allows us to play with images, like Félix and Brassens play with their guitar”]. Simple in execution but intricate in implication, “L’Âge des images” ought to be better known.

©Photo of Jean-Pierre Lefebvre by Lois Siegel

This essay first appeared in a French translation in 24 Images, March-April 2006, No. 126, pp.18-20.

Endnotes

1 Petite Esquisse, Un cinéma sous l’influence, 31

2 For a more complete discussion in English of this series, see “The Music of Light: The Video Work of Jean Pierre Lefebvre,” by Peter Harcourt. In Jean Pierre Lefebvre—Vidéaste, ed. by Peter Harcourt. (Toronto International Film Festival Group, 2001), pp. 17-52

3 CinéBulles, 37