David Owen Russell’s I ♥ Huckabees

Laughter and Philosophy

“In life, a man commits himself, draws his own portrait and there is nothing but that portrait,” wrote Jean-Paul Sartre in “Existentialism and Humanism,” Basic Writings

“In fact we are not in possession of our faculties; we are possessed by them. We do not really think; we are thought.”

—Robert Linssen, Living Zen

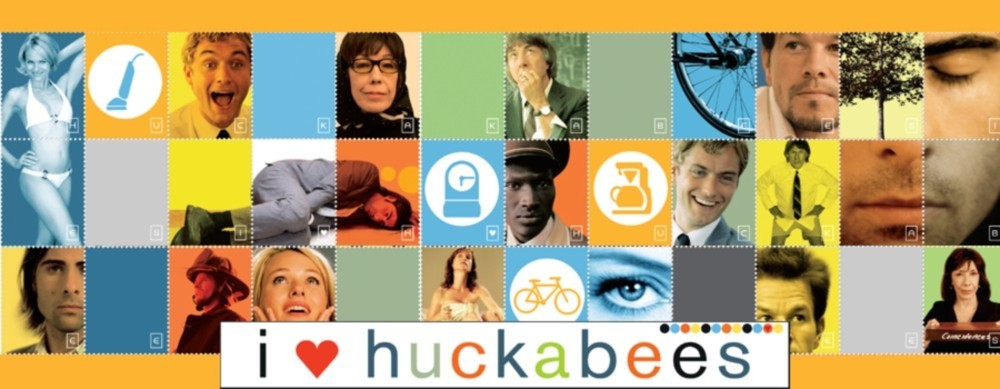

I hope, and imagine, that David Owen Russell’s I (Heart) Huckabees, or I Love Huckabees, is the kind of film that will be more appreciated with time’s passage. It is a philosophical farce focusing on existence, politics, the effects of capitalism, and personal relationships, and it is fun. The story revolves around an environmental activist negotiating with a chain store over the development of a natural area, and it stars Jason Schwartzman, Jude Law, Dustin Hoffman, Lily Tomlin, Mark Wahlberg, Isabelle Huppert, and Naomi Watts. The film is an original creation of a discriminating intelligence; and, although an entertainment, it assumes what art and criticism assume—intelligence and humanity—and it is a test of our ability to think through ideas and respond to more than two persons at a time, especially when those persons are different in character, thought, and values.

David Russell, like the lead character in I Heart Huckabees, did work on behalf of the environment and labor unions after graduating from Amherst College, where he studied english and political science. Russell studied with novelist Mary Gordon at Amherst, and he has said that he admires writers Robert Stone and Thomas Pynchon and the film director Luis Buñuel. The (Larchmont) New York native worked as a union organizer in Maine, and his video documentation of a union campaign led to his desire to make films; and Russell made three short films Boston to Panama (1985), Bingo Inferno (1987) and Hairway to the Stars (1990), before making the feature films Spanking the Monkey (1994), about a young man’s incestuous relationship with his troubled mother; Flirting with Disaster (1996), a comedy about a search for biological parents; and the great Three Kings (1999), a film about war, politics, and a quest for gold. Russell locates the root of I Heart Huckabees in his high school reading of J.D. Salinger’s Franny and Zoey, and study of eastern philosophy with Robert Thurman in college; and he has said that the film contains the things he cares about most.

I Heart Huckabees, written by Russell with Jeff Baena, is very American in its directness and light spirit, while offering a critique of American values and institutions. American culture seems to prefer we be preoccupied with gossip, love, sex jokes, money, acquiring things, sports, music, ethnic tribalism, and an unimaginative two-party political system, all overseen by a very American god that never judges us harshly though it is likely to condemn what our neighbor is doing. The film is actually often astute emotionally—it gives us a central character that seeks help for a concern that turns out to be only a symptom rather than his main trouble, something that suggests both sensitivity and self-deception. Russell gives us a loving couple, one other than expected, Lily Tomlin and Dustin Hoffman as existential detectives and teachers; they are married, middle-age, and share work and significant spiritual ideas. A masculine fireman, played by Mark Wahlberg, tries to come to terms with large matters, such as the effects of petroleum use and child labor, a commitment that alienates him from his wife and brings him a new friend in the environmentalist. The pretty pair, Jude Law and Naomi Watts, a marketing agent and a model, have their own existential crises—we all can suffer, we all can grow.

“I wanted it to be shot in a matter-of-fact, unfancy way. Not a lot of camera movement, pretty simple setups. I wanted it to be bright and open, not dark and muddy. We wanted a flat light, not a hard light. I associated it with New Jersey or the Valley, when things are overcast. In terms of décor, on the one hand I wanted interiors that were clean and open, like the interior of Huckabees or the detectives’ office, and on the other this strip-mall, could-be-anywhere, crappy-looking exterior world,” Russell told _Film Comment_’s Gavin Smith (September/October 2004). That is an unusual atmosphere, captured by cinematographer Peter Deming, for such a speculative film in which the lead character encounters forms of eastern philosophy and existentialism.

Eastern philosophy, of which Buddhism is a principal part, is an ancient thought that focuses on existence and on practice; and Buddhist philosophy posits four fundamental facts or truths—suffering, ignorance, deliverance, and spiritual discipline—and spiritual discipline includes pursuit of correct vision, intentions, speech, conduct, life style, effort, attention, and concentration, the eight-fold path. “Zen asks us to bring to bear the intensity of an extraordinary attention in the midst of all so-called ‘ordinary’ circumstances,” wrote Robert Linssen, Living Zen (174). Zen is a Japanese name for a mix of Buddhism, inspired by the enlightenment of an Indian prince, and Taoism, a Chinese philosophy in which nature is important (its central text is Tao Te Ching, attributed to Lao Zi or Lao Tse, and Zhuang Zi or Chuang Tse)—and many of Taoism’s traditional practitioners, skeptical of human institutions and in search of freedom, were loners and poets. Tao is a way of life; and Tao’s circular yin-yang symbol stands for a balance of opposites (Yin is dark, moon, woman, and Yang is light, sun, man), in which dark includes light and light includes dark. Zen followers seek to exist in the moment; and, encouraged to seek action that is in accord with nature (this can mean avoiding conflict), often sit—meditating. Existentialism, a twentieth-century French philosophy influenced by the Enlightenment and the French Revolution in its regard for individuality, also contemplates existence, and sees existence as solitary and as meaningless until human choice and effort invests it with meaning; and it is a philosophy often summarized by the aphorism that existence precedes essence. While both eastern philosophy and existentialism emphasize individual consciousness (with Eastern philosophy encouraging transcendence of self, and existentialism seeming a way of constituting a self), how we choose to act alone and with others is to both philosophies of defining importance.

I Heart Huckabees has received a rather mixed response. It was welcomed in The Village Voice (September 29-October 5, 2004) with an enthusiastic article by Dennis Lim, who wrote, “If Russell’s blithely profound mishmash of screwball Sartre and zany Zen seems incongruous, it’s because movies have historically consigned existential musings to the more passive and agonized sectors of art cinema. Huckabees, like Russell’s other films, is furiously active, bordering on unhinged, and its farcical tone proves ideally suited to philosophical striving: The movie acknowledges that to undertake such a quest is often to risk ridicule, even as it reconnects existentialism to a rich tradition of absurdity. ‘A Zen monk once told me, If you’re not laughing, you’re not getting it,’ Russell says. ‘These questions are absurd in some respects. Sometimes you cry because of the absurdity. Some people say that you talk about the serious stuff and then you put in comedy to make it go down easier. But no, they’re one and the same.’ ” Armond White, who noted the film’s philosophical rigor as its most appealing quality, wrote in the September 29-October 5, 2004 New York Press, “David O. Russell is among that group of contemporary filmmakers (along with Wes and P.T. Anderson, Spike Jonze, Alexander Payne, Sofia Coppola and others) currently tweaking the system. A friend calls this new breed the American Eccentrics, a good categorization since it distinguishes these upstarts from that last significant grouping of 70s filmmakers who were drawn to exploring American experience and pop tradition in order to understand their place in the world. The Eccentrics, formed by the fragmentation and solipsism of the 80s indie movement, are more interested in their personal idiosyncrasy. They don’t connect to life outside their own world but view it as absurd and different. Films like The Royal Tenenbaums, Punch-Drunk Love, Adaptation, Lost in Translation and Russell’s I Heart Huckabees reinforce a sense of boomers’ egotism; as with Payne’s About Schmidt, there is an insistence on braininess rather than connection with popular sentiment.” Ella Taylor in October 1-7, 2004 issue of LA Weekly described the film as “fresh, buoyant, mischievous and rather jolly meditation – if that’s the word for a movie as divinely nuts as this one is – on the meaning of life in an unhappy world.” Lim describes the movie as balancing an almost unfeasible amount of ideas, White says the film only works about half the time, and Taylor says it’s undisciplined and over-plotted: and these are the good reviews.

Andrew Sarris, who was repelled by some of the advance publicity for the film but encouraged to see it by his students, wrote in the October 18, 2004 New York Observer, “It is difficult for me to describe how sweet and buoyant I found the film, despite its seemingly excessive stylization. The whimsical, 46-year-old David Owen Russell, of Hairway to the Stars (1990), Spanking the Monkey (1994), Flirting with Disaster (1996) and Three Kings (1999), is fully in evidence here, but with even more audacious whimsy than before, and with a less conventional narrative structure. Huckabees is, in contemporary parlance, way more ‘out there’ than any other American movie you are likely to see this year. Yet it is also compelling enough for me to make my 10-best list.”

When I Heart Huckabees begins, Albert Markovski (Jason Schwartzman), a poet and environmental activist, in long uncombed hair and dressed in a suit for a press conference, walks through the woods. He is cursing, using words describing intimate relationships with both a mother and the male sex organ. His curses are interrupted by his speculation about whether his work is any good, and reference to an African guy (Ger Duany) he has been seeing around town, coincidental meetings he’s inclined to interpret as a sign. Anger and self-doubt, and also ambition, are aspects of his personality we will see throughout the film. Albert stands in front of a large rock and reads a very simple poem about the existence of the rock (it just sits); and it seemed a very bad poem to me. Albert, before a small audience of activists and press, is memorializing the rock he has protected and which he identifies with a simple existence.

The poet Wendell Berry who has written on the relationship of men and women to language, nature, and business has said in an essay, “With Nature” (Home Economics),

If the human economy is to be fitted into the natural economy in such a way that both may thrive, the human economy must be built to proper scale. It is possible to talk at great length about the difference between proper and improper scale. It may be enough to say here that that difference is suggested by the difference between amplified and unamplified music in the countryside, or the difference between the sound of a motorboat and the sound of oarlocks. A proper human sound, we may say, is one that allows other sounds to be heard. A properly scaled human economy or technology allows a diversity of other creatures to thrive. (16)

The local press is there to cover Albert’s environmental activism, and the press conference is very brief—Albert is soon off riding his bike to the office of two environmental detectives, Jaffe & Jaffe. He walks, and runs, through a maze-like hallway to get to their office, where he meets with Lily Tomlin’s Jaffe, who talks to him in a deep throaty voice and observes him. Albert had found the firm’s business card in a jacket borrowed in a restaurant, where he was meeting Brad Stand (Jude Law), a representative of a chain store, Huckabees, and someone Albert’s working with in a coalition to save a marsh and nearby woods. Tomlin’s Jaffe tells Albert that she and her partner would have Albert under surveillance; and through watching Albert, they would come to understand his existence.

Jason Schwartzman’s Albert says that he wants the detectives to investigate the coincidence of repeatedly seeing a tall African man. He says he saw the African when he was in a photo shop getting photos of Bob Dylan (we’ll later learn he was actually planting photos of himself there with his poems); as a doorman to a friend’s apartment building (actually, Albert’s mother’s apartment); and inside a van while Albert was planting a tree in a parking lot (trying to reverse the “they paved paradise and put up a parking lot” thing). The African was collecting signed photographs of various personalities, such as Shaquille O’Neal, when Albert first saw him; and one imagines the rarity of such a figure as the African in Albert’s world is why the man has stayed in Albert’s mind.

“Have you ever transcended space and time?” asks Tomlin’s Jaffe, a provocative question. Albert (Schwartzman) hedges before admitting he’s not sure what she’s talking about. He asks her to stay away from his job, as he’s having conflicts there that he would not like further complicated. This indicates an inclination to separate his life into sections, something the detectives are not likely to accept. The agency offers a sliding scale of payments, depending on ability to pay (they’ll help Albert pro bono); and Albert is introduced to Tomlin’s colleague, Hoffman’s Jaffe, and Tomlin and Hoffman kiss, which seems disconcerting at first, not what one expects in a professional office, though Hoffman will casually mention that the two are married. First Hoffman’s Jaffe shows Albert a blanket that Jaffe says represents the universe, and Jaffe raises different points in the blanket to suggest various people and things, saying each is different but connected—all part of the same blanket or matter. (“The sight of Mr. Hoffman, who’s in excellent form here, brandishing a blanket to explain how every particle in the universe connects together is an image of incomparable goofiness in a movie filled with irresistible nonsense moments,” wrote Manohla Dargis in her October 1, 2004 New York Times review.) Hoffman’s Jaffe says that we need to learn to see our connection as part of our everyday perception. While Vivian Jaffe will closely observe Albert’s daily habits, Bernard Jaffe will try to help him change his way of thinking. Bernard asks Albert to get into a dark black bag, a kind of isolation chamber, in which images of reality fall to reveal basic concerns or preoccupations. We see the face of Jude Law’s Brad Stand, and the tall Sudanese African in uniform, and then memory of a lunch between Albert and Brad Stand talking about the Open Spaces coalition and Huckabees and how the two men might work together. Brad admits that he knows that working with the coalition will be good for Huckabees’ image but he’s doing it because he really cares—a smooth way of being honest and forthright about one’s commercial concerns. In Albert’s black bag imaginings he hacks at Brad’s face with a long blade; and we see other faces of people with whom Albert’s argued—and Albert slices them.

Albert begins to incorporate some new practices into his life—we see him in the bath with an eye mask, trying to become more intimate with his feelings and conflicts so that he can accept them and attain peace. He eats breakfast and brushes his teeth, and Vivian Jaffe is outside Albert’s apartment window taking notes. He goes to a parking lot to hand out flyers of environmental concern and workers throw food and garbage in his face. Vivian, against his wishes, visits Albert’s office, planting listening devices as she goes; and she learns that he is fighting suburban sprawl and wants to know more, while he insists that the coincidence he wants to investigate involves the tall African man. Bernard Jaffe talks to Albert again about the interconnections of reality and how Albert can learn to break down his usual way of seeing things: and we see cubes of Bernard’s face separate, float, and fall, likely manifestations of director David Russell’s appreciation of the surrealists Magritte and Duchamp. (The graphics, or special effects, have a very human quality—they seem made by men rather than machine, and that lends them charm, just as the music by Jon Brion sounds as if it is performed by a band rather than an orchestra: the graphics and the music do not overwhelm.)

The existential detectives get a call about their client Tommy Corn (Mark Wahlberg)’s crisis with his wife, who is leaving him. Vivian dives into the car of Angela, a coalition member who has been arguing with Albert, and is in the backseat when Angela drives off to a coalition meeting, while Bernard goes to Tommy’s house. Firemen are helping Tommy’s wife move out of the house (and it did seem odd to me that Tommy’s fellow firemen would be helping his wife move out of the house, though it’s possible that his wife has friends and relatives who are firemen). “If nothing matters, how can I matter?” asks Tommy’s wife, a rather understandable response—she is actually taking his philosophical inclination seriously by seeing its practical application; but this also indicates an inability to tolerate philosophical speculation. “She won’t stay and share this with me,” says Tommy, who attempts to explain his wife’s selfishness to their daughter and shows Bernard a book, Caterine Vauban’s If Not Now, a pessimistic view of life. Vauban, played by Isabelle Huppert, is a former associate of Bernard and Vivian Jaffe; and Vauban will follow Vivian and begin to interfere in the detectives’ cases. Tommy hits a fireman who calls Bernard his therapist.

Meanwhile, at a corporate meeting Jude Law’s Brad is telling a story that’s “only four months old” involving country singer Shania Twain and her disaffection for chicken salad and mayonnaise sandwiches, a story that indicates how persuasive Brad can be even with a self-directed celebrity. Tomlin’s Vivian Jaffe infiltrates the meeting to plant a listening device, then wanders the halls and is escorted back by a sharp receptionist, something that easily conveys the controlled atmosphere of such an environment. There’s a poster of Shania that Vivian sees, stopping; and “Shania has no song for you,” the receptionist says, and Vivian sees Naomi Watts’ Dawn modeling before leaving. Dawn is the voice (and face) of Huckabees. That Dawn is called the voice of Huckabees seems a bit of overt foreshadowing of a time when her face may no longer be seen.

Albert sits on a large rock, the one we saw at the beginning of the film, the rock he “saved.” “We go to wilderness places to be restored, to be instructed in the natural economies of fertility and healing, to admire what we cannot make. Sometimes, as we find to our surprise, we go to be chastened or corrected. And we go in order to return with renewed knowledge by which to judge the health of our human economy and our dwelling places,” wrote Wendell Berry in Home Economics (17). Albert wonders, Is it possible for anyone to make this world better? “I cannot tell, I only know that whatever may be in my power to make it so, I shall do; beyond that, I can count upon nothing,” wrote Sartre in “Existentialism and Humanism,” Basic Writings (36).

“Any thinking person finds it hard not to be brought down into depression by a world convulsed by senseless wars, famine, melting icecaps, the desecration of wilderness areas for oil, and the continued malling of America by corporate interests whose capacity for Orwellian doublespeak boggles the mind. Try to name one recent Hollywood film that has even bothered to allude indirectly to these subjects and you will come up blank. That’s one reason to support this one,” commented Frederic and Mary Brussat of the online publication, Spirituality and Health, in their review of I Heart Huckabees, accessed November 6, 2004.

We learn, during a coalition meeting, that a coalition member’s father deeded the marsh and woods to the town. Brad tells the members that their campaign has to reach people quickly with images, including that of singer and nature advocate Shania Twain, not the poetry that Albert prefers. (Vivian introduces herself to Brad.)

In a meeting with Albert, Vivian and Bernard tell him what they have learned. Vivian says that rather than looking for a Dylan photograph when he saw the African in the photography shop, Albert was planting photos of himself and his poems, an obvious desire for attention. The desire for public attention is not all that hard to understand in a world in which anonymity renders one inconsequential and fame seems to confirm one’s existence. Albert also looked in the shop at photographs of Jessica Lange, whom Dawn resembles. “Do you only have fantasy relationships?” the detectives ask him, before getting him back into the black bag, in which memories of Naomi and Brad come. Albert sees, or imagines, a tree; and Bernard tells him to add someone he respects to the scene—and Brad appears, sitting in the tree. Obviously Albert has an attraction-repulsion response to Brad, respecting Brad’s success while resenting his values. Then, Brad is joined in the tree by Albert’s favorite high school teacher, and Brad pushes her out of the tree. She comes back and Brad chops her head off, then Albert slices Brad up. This is a rather terrific way of conveying violent impulses that resonate as true—human, common—but that are hard to accept.

The use of a tree as part of Albert’s meditative imagery is in line with his environmental activism; and it also calls up a human response that is both poetic and spiritual. Wendell Berry wrote an essay, “The University,” that talked about letters and numbers (including history, literature, and philosophy in the former, and biology and physics in the latter) as the basis of educational study and noted the contemporary tendency toward specialization, the lack of shared wisdom; and Berry tried to suggest the importance of maintaining basic connections among words, things, and meanings, using a tree for an example.

It is necessary, for example, that the word tree evoke memories that are both personal and cultural. In order to understand fully what a tree is, we must remember much of our experience with trees and much that we have heard and read about them. We destroy those memories by reducing trees to facts, by thinking of tree as a mere word, or by treating our memory of trees as ‘cultural history.’ When we call a tree a tree, we are not isolated among words and facts but are at once in the company of the tree itself and surrounded by ancestral voices calling out to us all that trees have been and meant. This is simply the condition of being human in this world, and there is nothing that art and science can do about it, except get used to it. But, of course, only specialized ‘professional’ arts and sciences would propose or wish to do something about it. (Home Economics, 80)

We see Naomi Watts’ Dawn in a commercial in which she’s smiling and posing, draped in patriotic colors, red, white, and blue. Dawn seems perfectly happy—it’s arguable that she’s found her life mission: to look good and get paid for it. It may well be an act of violence to bring new, complex thoughts to her awareness.

Brad is in Bernard’s office and Bernard films him reading a poem. Albert walks in and sees this, noting that Brad doesn’t write poems and has borrowed some of Albert’s ideas for his poem. Bernard suggested Brad write the poem, indicating Bernard wanted Brad to experience something of value to Albert; and Brad used the nearest reference he had to accomplish his writing assignment—Albert. Albert says that Brad wants to conquer the detectives (his detectives?) the way he conquered the coalition, suggesting the power and seduction and seductive power involved in all kinds of relationships, professional and political.

Vivian decides to introduce Albert to Tommy Corn (Mark Wahlberg); each is to be an “other,” part of an existential pair, a self both different and connected. When Vivian brings Albert to Tommy, Tommy is listening, somewhat mystified, to a black-garbed Spanish woman talking rather mournfully and the woman is described by Vivian as a spiritual petit four (a small square-cut piece of cake). “Why do people only ask themselves deep questions when something bad happens,” asks Tommy, who is permitted one question but asks three: it is hard to regiment genuine spiritual questions or torment. [There are real world web sites established for the Huckabees corporation, Jaffe & Jaffe, and Tommy Corn, accessible as of October 2004, and on Tommy’s he asks these three questions: “Why is it that people only ask themselves deep questions when something really bad happens, and then they forget all about it later? How come people are self destructive? I refuse to use petroleum but there’s no way I can stop its use in my lifetime, is there?”]

“I’ll be your other,” says Tommy to Albert; and his words and tone have a factuality and a friendliness that are manly while also seeming somewhat sweet. (Tommy’s last name, Corn, suggests something that is of nature and sweetness.) Andrew Sarris called Tommy the film’s most likable and sympathetic character. Tommy is affected by the World Trade Center destruction of September 11, 2001; and Russell told Film Comment, “For about two months after 9/11, people were asking really profound questions about reality and existence—and then it was back to business as usual, whether politically or existentially. Tommy is the kind of person who uncompromisingly grabs onto something and he’s not going to go back to business as usual.”

Vivian announces what I heard as a mancala hour (mancala is a board game and I think we see, very briefly, at least one shot of a board game in progress); and there is music, drinking, and dancing. Tommy and Albert talk, and Tommy says his own life seems to him now more like the philosophy of Caterine Vauban, rather than the optimism of Jaffe & Jaffe. Albert challenges Brad’s interest in philosophy and asks him to name a recent book he’s read and Brad names a book by sportsman Phil Jackson, Sacred Hoops. Albert wants to see his own file; and to distract the others, Tommy insults Brad and dances with Naomi, an unromantic romantic moment (form without feeling)—and Albert retrieves his file with the African’s address, and Albert and Tommy go to see him. The African, Steven Nimieri (Ger Dusany), is a young Sudanese refugee who is living with a white Christian family in the suburbs; and Albert and Tommy ride their bikes to where he lives. (“What other movie of this century features two heroes who ride bikes? Now there’s something that is genuinely countercultural!” wrote _Spirituality and Health_’s Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat, of this “daring metaphysical comedy.”) Albert and Tommy join Steven and the family for a spaghetti meal, at which a prayer is said; and Albert and Tommy learn that Steven collects autographs and autographed photographs as it is part of this family’s activities, but, after attempts at conversation, there is an argument over values and politics. “If the forms of this world die, what happens to the infinite aspects of the self?” Albert asks. What happens in a meadow at dusk? “Everything,” says Albert. “Nothing,” says Steven’s adopted mother. “We took a Sudanese refugee into our home,” the father says self-righteously. Why did they do that, and why were they needed to do that? “Could that have to do with support of dictatorships?” asks Tommy, implicating the American government in Africa’s instability. Albert and Tommy are ordered to leave; and Albert concludes that the previous coincidence of meeting Steven was meaningless. (Isabelle Huppert’s Caterine Vauban, the dark lady of French philosophy, is in a white limo nearby, observing.)

The environmental organization director above Albert gives him a chance to speak at the coalition’s meeting. Albert says that the coalition is overlooking the core issues; and he reads a poem. “Poems help you to think differently,” says Tommy. Brad claims Albert is unfocused (they each see a problem but ascribe it to different causes, just as in American party politics); and Brad is elected coalition leader, to Albert’s hurt and anger. (David Russell has said that Jude Law seeing the three characters—Albert, Tommy, and Brad—together, described them as archetypes of the artist, working man, and capitalist.) Albert, rather than accept Brad’s leadership, leaves. Does that mean he doesn’t respect the democratic process of the group and the resulting selection; or that the selection indicates that he and the group no longer share goals or values, and have no basis in working together? Tenzin Gyatso, the Dalai Lama, a practitioner and advocate of inner transformation through spiritual discipline of the mind and body, talks about the importance of self-understanding, which affects responses, as self-understanding leads to an ability to tolerate criticism, fair and unfair, and an ability to learn from various situations, comfortable and uncomfortable. The Dalai Lama says that utilizing personal strengths can transform work into a calling; and the commitment to that calling is not limited to a particular activity or role (The Art of Happiness at Work, written with Dr. Howard C. Cutler); so, for instance, if Albert wants to be of use to people, he might do that in various roles, not only as leader.

Tommy recommends that Albert give Caterine Vauban’s cynical—or realistic?—philosophy a chance; and it is so that in our weak moments someone will offer us a questionable option. Albert angrily takes off on his bike, with Tommy not far behind and the existential detectives attempting to follow. Vauban tells Albert she can answer his questions. “Betrayal embodies the universal truth,” she says. What is the truth? Cruelty, manipulation, meaninglessness; and her business card carries that motto. Caterine Vauban drives Albert and Tommy to Albert’s mother’s apartment, where the African doorman Steven works. Caterine hands Steven a note. Albert’s mother (Schwartzman’s own mother Talia Shire) criticizes Albert for losing his job and hands him information about marketing work—she thinks his language skills should be used to sell things, a familiar belief (she’s telling him also, unknowingly, to become Brad). Albert’s stepfather puts on Shania Twain music. Caterine finds Albert’s childhood notebook in which he describes his mother’s unsympathetic response to his cat’s dying, drawing attention to his mother’s inclination to give a stranger more attention than her son. His mother says to Caterine, “What are you, a bitch? You’re a bitch—this is a bitch. How many children do you have, bitch?” (Whereas the vulgarity that began the film is somewhat startling, the vulgarity and outrage are here weirdly funny.) Steven comes up to the apartment, as Caterine asked, apparently, in her note, and Caterine says, “Steven was orphaned by civil war and Albert was orphaned by indifference.” They leave the apartment; and in the elevator both Albert and Caterine have tears in their eyes. “You were trained to betray yourself,” says Tommy, who talks about the cracks in between the connections that Jaffe & Jaffe advised them to see. Vivian says that the detectives would have been able to help Albert if he had been more honest, if he hadn’t misled them about the link between Steven and Albert’s mother. (The unspoken idea is that in being unable to trust his mother Albert has learned to distrust other figures of power, something that has helped him to be an individual and an activist, but that leads to self-betrayal when he distrusts benevolent figures of power.) Bernard says that just because you cannot see the connections he names does not mean they aren’t there; and he says that he and his wife will work on Brad and it will all come back to Albert, an indication that Brad is also Albert’s other.

Both eastern philosophy and existentialism allow for the confirmation of our existence by an other or others. Caterine’s philosophy is actually more extreme than anything someone like Sartre would typically say. In “Existentialism and Humanism,” Sartre wrote that “every truth and every action imply both an environment and a human subjectivity” (26). He noted that although people were calling existentialism pessimistic, there was more pessimism in ordinary common sense, which often embodies fear of authority and admonition not to defy tradition, and that existentialism—a form of thought for technicians and philosophers—represented a rather severe optimism. “Existence comes before essence” (27)—which meant, he explained, that “man first of all exists, encounters himself, surges up in the world—and defines himself afterwards” (28)—there is no god and no human nature. The choices of men—and women—inevitably have the weight of symbolism, as they are possible ways of being in the world for others. There can be a certain anguish in this (and, I think, exhilaration); and the anguish does not prevent action, though it may accompany it. Sartre wrote that “feeling is formed by the deeds that one does; therefore I cannot consult it as a guide to action” (34); and “You are free, therefore to choose—that is to say, invent. No rule of general morality can show you what you ought to do: no signs are vouchsafed in this world” (34). Sartre affirms thinking and acting and the comprehensibility of both by others.

Bernard and Vivian go to Brad’s house, making their way around the lawn sprinklers. They look into his trash for clues—clues Brad has planted, such as work by or about Kafka; and inside the house Dawn has found Brad’s poem about unhappiness. She wants to know what the poem and the existential detectives are all about, what they imply about the relationship between Brad and Dawn: she reads the poem as incriminating, just as Tommy Corn’s wife read Tommy’s new beliefs as repudiation. Brad says the detectives, like him, are pro-active; they do and change things. The detectives point out his need to charm. Brad, who inadvertently mentions the pressure for successful people to marry and produce children, and Dawn both admit that their sex life is often brief (eight or nine minutes); she tries to say that quality not quantity is important but, in an obvious Freudian slip, reverses the terms—twice. Brad’s business associates arrive and he goes out, and Dawn is left to talk with the detectives.

Tommy hits Albert in the face with a ball, an exercise suggested by Caterine, in which sensation stops thought—and allows pure being. (It’s a Zen exercise.) “Fantastic,” says Tommy. “I’m free to just exist,” says Albert. They think they can do this hitting always to maintain that feeling. (Does that suggest something about the appeal of physical activity, such as sports; and if so, was Brad’s reference to sportsman Phil Jackson’s philosophy on point? In the book Brad mentioned, Jackson not only writes about the Chicago Bulls basketball team but about Jackson’s appreciation of Zen.) “You cannot stay in this state all day—it’s inevitable you get drawn back to human drama,” says Caterine: we go from pure being to human suffering and back again. Tommy doesn’t quite believe this; and Caterine says she’ll demonstrate the idea—and immediately begins to flirt with Albert, putting her foot into his lap. Caterine and Albert go off into the woods without Tommy. Caterine pushes Albert’s face into a mud puddle; and he covers Caterine’s legs and face with mud and they kiss—it seems a homage and burlesque of Catherine Deneuve in Belle de Jour (Deneuve had been mentioned as a possible Vauban). Albert and Caterine are both soiled, and they accept each other—in this moment, they do not require the pristine or the perfect. Caterine and Albert have sex, doggy-style; and I laughed hysterically at the mud-and-sex scenario the first time I saw it, even as I wasn’t sure if it was really funny (which is to say, it was funny though it defied my own expectations and taste).

Dawn is in overalls and white hair bonnet as Brad leaves for work. “You look ugly,” he tells her. Dawn says she’s been changed by the existential detectives; and mentions she’s filmed some new, different marketing spots for Huckabees. Brad tells her that she doesn’t have to listen to everything the Jaffes say; and she says, “How am I supposed to know which parts to listen to?” (A question that echoes the introduction of various philosophies into our lives; and that indicates her lack of intellectual preparation.) Huckabees does not like the new Dawn or her new spots; and has hired a bosomy young model—they’ll use Dawn’s voice and Heather’s body. Dawn goes on the war path when she learns this—attacking the replacement, mooning a business meeting, and lying on a desk top as Brad tries to talk to her (“I’m in my tree, talking to the Dixie Chicks,” she says). Brad tells her that he only went to the detectives to help get Albert out of the coalition. Dawn asks if he cares about the marsh and woods? He says yes, before telling her to leave the building through the back door because of how she looks.

Tommy is at a fire, then at Albert’s rock, seeming lonely, and then he enters a bedroom where Caterine and Albert have been trysting. He talks about feeling abandoned and asks if Caterine did this just to teach him a lesson, before saying that he’s going to an even darker spiritual place than the one she has supposed; and she’s pleased: she says, “Sublime.” (Caterine whose philosophy is trouble is soon telling Albert that he has to disrupt Brad’s life as Brad disrupted his; and we see Albert lighting fire to a photograph of jet skis—it’s quite nearly a voodoo image.)

Now that Brad has what he wants, control of the coalition—and before the detectives further disrupt his personal life—Brad asks to close his existential case, but they refuse (the contract Brad signed specified the case cannot be closed before resolution; and he would be embarrassed if they pursued breach-of-contract charges). The detectives describe him first as passive-aggressive, then as aggressive-aggressive; and say they’ve been investigating his Cleveland family, and draw attention to his fat brother who collects plastic geckos and to whom Brad has given a car (movement) and shirts (appearance). Jude Law, clever and flirtatious in Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow and smugly seductive and heartbreakingly remorseful in Alfie, is here, as Brad, a believable corporate suit. The detectives ask him about the stories he likes to tell, such as the Shania sandwich story, and when they play a tape of his repetitive telling of the Shania story, Brad’s self-confidence becomes doubt. “How am I not myself?” he asks; and they repeat the question—and he is left with it and it begins to undermine him and when he’s in an executive meeting and he is asked to tell the Shania story he becomes nauseated. Told by the detectives that his stories are propaganda for himself, for his public image, and unable to contest this, he is in crisis. “Because we no longer know how to be_…, we seek to _become_” says Robert Linssen in Living Zen (99). We see men like Brad or whom we fear are like Brad, all shiny surfaces and shrewdness, slipperiness itself, men who always seem to be saying yes though we cannot always locate their names on a signed agreement. “How am I not myself?” is a question that David Russell told Nathan Lee of _Filmmaker magazine, Fall 2004, that he hopes audience members will ask themselves.

Tommy, seeming somewhat depressed, is summoned with his department to a house fire, and he goes on his bike, and is exhilarated by being able to continue to the house when his co-workers are stalled in car traffic. Tommy arrives at the burning house—Brad and Dawn’s—before the rest of the department; and he finds Dawn amid smoke in a bonnet and overalls and they look into each other’s eyes and kiss. The fire, we deduce, has been lit by Albert with Caterine’s encouragement; and they both observe the fire and its aftermath. When Brad arrives home—upset by the detectives’ questioning and his nausea at the board meeting—and sees the fire, Brad cries and Caterine takes a photograph of Brad’s crying face, which she gives to Albert. The photograph may be intended as commemoration of the moment when Albert vanquished his enemy, but in Brad’s sorrow Albert sees his own—and for a moment Albert hallucinates Brad’s face as Albert’s own face (cubistically, surrealistically). Having pursued Caterine’s philosophy, Albert sees the connections Jaffe & Jaffe earlier tried to show him. Albert imagines himself and Brad bonding in joy, an image both silly and brave; and Albert sees the differing philosophies of Caterine and the Jaffes as fragmented and overlapping—and wonders if they were secretly working together.

Brad, torn between accepting and disavowing his new state, goes to the benefit; and he is excluded from the proceedings, just as he made Albert feel excluded from the coalition Albert founded (these are two of several betrayals in the film). Dawn and Tommy find their way to the benefit. “Do you love me with the bonnet?” asks Dawn of Brad, who begins to shake his head, no; and as Tommy likes the bonnet, Dawn feels now more comfortable with Tommy. It seems a moment of bliss between Dawn and Tommy—and it’s unlikely to last, as this is an extreme phase she’s going through. Dawn, who is at the beginning of her spiritual development, has found a dramatic way of signaling her change to the world but she will likely move to integrating her various impulses and ambitions in a more conventional way. Her personal resolution then will be less visible and Tommy will likely doubt its existence—and they’ll fight and part, or so I predict. While Dawn and Tommy are going off on their own, Brad and Albert get on an elevator together—they have been each other’s enemies, and so share a strange intimacy—and they acknowledge their mutual aggression, but the larger world overtakes them. Huckabees has announced plans to protect the marsh but build a mall where the woods are. Brad is condemned by the coalition members. Albert admits to having torched Brad’s jet skis—the fire spread to the rest of the house; and Albert shows Brad the photo of Brad crying, asking, “Who is this, me or you?” It’s an attempt to get Brad to see their shared sorrow, their shared humanity, but Brad merely wants to retrieve the photograph of his own humiliation. Albert gives Caterine’s card to Brad.

Albert and Tommy sit on the rock, near where the film began, and they talk about inner connections that grow from the excrement of human trouble, while the three unnoticed philosophers, Bernard, Vivian, and Caterine, watch (I wondered about the staging of that—whether the two young men would be able to see the philosophers). “What are you doing tomorrow?” asks Tommy. “Thinking of chaining myself to a bulldozer,” says Albert, “Wanna come?” Tommy says, “Sounds good. Should I bring my own chains?” Albert tells him, “We always do,” a statement that seems practical and rich with implications—then the two begin to hit each other in the face with the ball, in search of pure being.

Stanley Kauffmann, before hoping that Russell’s career would resume as it was before Huckabees, wrote in the October 25, 2004 New Republic that the film’s characters “suffer from Russell’s ponderous directing of a screenplay that seems aimed to display his deep-dish erudition rather than to entertain us. (In how many films has Robinson Jeffers been mentioned?) The result is a doughy response to the Mystery of It All rather than, say, a Beckettian comic glimpse of the void. Russell’s inflated ambition has misguided his wit.” Slate_’s David Edelstein, who said Russell might be his generation’s most fearless talent, wondered if the film was dead from inception, and described the acting in the film as often cringe-worthy, remarking that Tomlin’s face seemed like a mask. (I thought Tomlin had the wrong kind of make-up when I first saw the film—her face seemed so white and taut, lacking the humanity of Hoffman’s face. However, at a second screening I attended weeks later I saw her pores and a more natural skin tone, and what bothered me at first was no longer a problem. I wonder if the amount of projection light—or something else—was adjusted for the second screening, assuming that all prints of the film were made from the same master.) Huckabees is weirdly impersonal with little genuine love or thought perceptible onscreen, claimed _Salon_’s Stephanie Zacharek. _New York magazine’s Peter Rainer called the film’s philosophy just a cover for slapstick comedy. David Denby called the film a disaster that yet could inspire loyalty, in The New Yorker. David Ansen of Newsweek said the film doesn’t work, though it’s stimulating, and is the kind of film we could use more of, the kind of contradictory response that may suggest the attraction-repulsion some Americans have for an art of ideas.

Russell told Film Comment_’s Gavin Smith that he wanted Huckabees to embody a “cinema of ideas. I’ve read Nietzsche and Sartre and Althusser, and all I can say is that I gravitate to the Eastern philosophers. But I like putting it in a secular context, because then all your conventions and assumptions about it aren’t there. I think the ideas stand up on their own” (September/October 2004). (Russell also told the _Village Voice_’s Dennis Lim that he likes that eastern philosophy never had a witch-burning phase.) One assumes that the films critics like are challenging, but what if that is not true? I had a conversation with an office clerk about a couple of critically acclaimed films that we had seen separately—films I would describe as thoughtful, as meditations on experience, films I loved that she found disappointing, even boring, describing them as _prolonged. Of course, critics do like films full of sensation, or heavy drama—in which mood, more than thought, conveys meaning; but I began to wonder if they (if we) like even more films so simple and slowly paced that they (we) can understand everything presented and can project their (our) own preferred ideas onto the films. A film that has its own many ideas, and conveys them with speed, resists such a method of operation. (I know that I have sometimes not tried to articulate a response to films I thought were too complicated.) I am encouraged to pursue this line of thinking when I consider certain critical comments. David Denby wrote, “The director has chaotic group scenes in which everyone is certainly part of everyone else—they glom onto one another, as if with sticky fingers—and he has better moments, when the comedy slows down a bit and he glories in individual quirks” (The New Yorker, October 4, 2004). The better moments are when the comedy slows down? David Edelstein wrote that “the picture moves fast—maybe too fast” (Slate, October 1, 2004). Peter Rainer compared Huckabees to works by directors Wes Anderson, the Coen brothers, Spike Jonze, and writer Charlie Kaufman, works he called “whoopee cushions for the Mensa crowd” in a New York magazine review available online October 6, 2004. Rainer stated, “Russell is hoping that the sheer volume of intellectual dither in this movie will propel audiences into the comedic stratosphere, but even astronauts know that there comes a time to touch down.” How does Rainer know what Russell hopes; and who decides when and how a film should touch down but the director? Why do the critical responses—which should be read in their entirety—of these decent, dependable writers seem unstable?

Why does Ansen write that the plot is not the point here, and then say that “Your mind is engaged and delighted as the movie bounces from philosophical thesis to antithesis to synthesis,” which summarizes the plot, the movement from the Jaffe theory to that of Vauban and then the combination of the two? Ansen also wrote, “You laugh, you smile—but your emotions don’t get much of a workout,” but if you’re consistently laughing and smiling, isn’t what you’re feeling pleasure, possibly very intense pleasure? Whereas Manohla Dargis described the film as “ambitious, heartfelt” in her early October New York Times review, noting its “passion, energy, and go-for-broke daring, in its faith in the possibility of human connection,” Rainer wrote that it would be nice if the film would “well, touch the heart,” and Edelstein claimed it has “zero emotional weight.” Why do we often think that pleasure is the opposite of real or deep feeling? Are the existential crises of Albert, Tommy, Dawn, and Brad being implicitly dismissed as inconsequential? Is that because these are crises of the spirit and of philosophy, not merely concern over sentimental and sexual love and unbelievable amounts of money, which are often what American films are about? Denby writes that Hoffman and Tomlin might have been a classic “nutbrain” intellectual couple if Russell hadn’t directed them to talk over and through each other (which I don’t think they do). Although I’m not entirely sure what nutbrain is, why would Russell want such a presentation, when he takes the ideas of their characters seriously? (Russell told Filmmaker magazine that he wanted the detectives to have a somewhat European formality, to suggest familiarity with the issues involved.) In an interview with Nathan Rabin in the satirical newspaper _The Onion_’s October 7-13, 2004 edition, Russell said, “When you go to see a more independent-minded film, it used to mean it was a film that was going to challenge your point of view. Now, a lot of times, people are going to reaffirm their credentials. ‘My ironic, cynical credentials are…’ ‘Please stamp my hand. I still belong in the same cynical, ironic club.’ One of the weird things about the film I’m proud of is its sincerity.”

One key to the confusion may be in perceptions of Jason Schwartzman, who I found intense, quirky, and very attractive. I felt Schwartzman more attractive a presence than Jude Law, just as I felt there was something fundamentally sexy about Lily Tomlin, more so than Naomi Watts. I usually find Law and Watts luminously complete and completely luminous. One can imagine the situations that influenced the personalities, philosophies, and styles of Schwartzman and Tomlin, whereas Law and Watts, two golden beings, may have been grown in laboratories. The film uses Law and Watts as exemplars of shallow beauty, though neither actor lost my interest. Without finding fault with the performances of Law or Watts, I have reservations about the use to which they are put, its symbolism, which may be inspired by a petty resentment, a loser mentality: is it necessary to bring them low (to our level)? Why does it seem too hard to identify with the ambition, commitment, drive, and sheer joy of success, enabling us to use someone else’s success—their achievement of their goals, whatever they might be—as inspiration for our own very different lives? We could have seen Brad’s humanity without learning he’s a nine-minute lover, seeing him vomit, or having his girlfriend go off with a blue-collar working guy. Men like Brad are constantly jumping through hoops, visible and invisible—that’s the price of their prominence; and to suggest that, as occurs in the initial “How am I not myself?” scene, allows him his humanity and his dignity. What did the critics say about Schwartzman? Stanley Kauffmann called him ungainly, and Peter Rainer called him the dullish center of the film, and even Andrew Sarris said he lacks charm, though one might predict that Schwartzman will become a leading man in a way similar to his co-star Dustin Hoffman. The film presents Schwartzman’s Albert as a conflicted hero but a hero he is—and he does not seem to have been accepted genuinely as such by the cited (sighted?) critics. David Russell said that when he had seen Schwartzman in an earlier film, Rushmore, Russell thought of Schwartzman as a brother, as someone he had to become friends with (and subsequently did befriend). That is a very intimate identification; and in Albert, a character with autobiographical roots, the identification is doubled (“I was the character that Jason Schwartzman plays,” Russell told Film Comment). To reject the character and the actor who plays him is to reject an important part of the form and the content of Russell’s vision.

I do not know that I would go so far as to say that Russell has created a new form, but he may have invented a new sensibility. The only works I can think of, at present, other than those previously suggested, as being at all similar are Gore Vidal’s satirical inventions such as Myra Breckenridge (on sexuality) and Live From Golgotha (on Christian tradition) and Charles Johnson’s Oxherding Tale (a consideration of identity and slavery, from a Buddhist perspective), and possibly films such as the political film Wag the Dog and The Truman Show, which suggested the lengths to which a society would go for entertainment, works that are serious at their core and use comic speculation as the main part of the text; and there may be other works I’m not thinking of, or am not aware of, and that’s part of a larger problem—things that do not fit easily into established traditions are often forgotten. There are films that are like dreams (watching them, one feels submerged, compelled), and imaginative though it is I Heart Huckabees is not one of them. Rather, this film is about becoming awake and one has to be awake to see what’s in it (there seem to be an unusual number of errors in the reviews the film has received, even in the reviews that approve of it: David Denby misreads Tommy as not very bright; Andrew Sarris writes that Dawn started the house fire as part of a suicide attempt and that Albert and Brad were former best friends; Armond White refers to Dawn as Brad’s trophy wife; and _PopMatters.com_’s Cynthia Fuchs writes in an otherwise observant, thoughtful review that Albert does not learn the significance of the African. I hesitate to consider what I have not perceived). Roland Barthes once wrote that the commitment to understand and explain the difficult is part of the critic’s responsibility, part of what constitutes his or her authority; and Pauline Kael once wrote that a film critic requires for nourishment –including to be able to write good criticism– more than a diet of movies: and I think this means that when reviewing texts, whether those of literature or film, certain works require more of us and we have to bring to bear substantial resources: and David Owen Russell’s I Heart Huckabees may be one such challenging film. Gavin Smith, Dennis Lim, Armond White, Ella Taylor, Andrew Sarris, Manohla Dargis, and Frederic and Mary Brussat, have come closest to satisfying those standards regarding the film.

“Man and woman and their social life, poverty, labor, sleep, fear, (and) fortune, are known to you. Learn that none of these things is superficial, but that each phenomenon has its roots in the faculties and affections of the mind. Whilst the abstract question occupies your intellect, nature brings it in the concrete to be solved by your hands” (61), advised Ralph Waldo Emerson in his essay “Nature,” now collected in The Spiritual Emerson. Emerson, who described his own age as retrospective, evidenced by the writing of criticism, biography, and history, wrote that the relation between mind and matter was contemplated from the time of “the Egyptians and the Brahmins to that of Pythagoras, of Plato, of Bacon, of Leibnitz, of Swendenborg” (38); and Emerson, who believed as does Wendell Berry in the reality of a supreme being (unlike most existentialists and many Buddhists), also wrote that “A leaf, a drop, a crystal, a moment of time, is related to the whole, and partakes of the perfection of the whole. Each particle is a microcosm, and faithfully renders the likeness of the world” (43). Such thoughts find their reflection in David Owen Russell’s I Heart Huckabees, which I think is, like his Three Kings, a necessary film in American culture at this time; and I Heart Huckabees, which makes the getting of wisdom seem not only a matter of conflict and tears but an adventure, serious fun, may come to be perceived as an important American film, evidence of American civilization. Wendell Berry wrote in “Work Song” featured in his Collected Poems (187-188):

If we will have the wisdom to survive,

to stand like slow-growing trees

on a ruined place, renewing, enriching it,

if we will make our seasons welcome here,

asking not too much of earth or heaven,

then a long time after we are dead

the lives our lives prepare will live

here, …

References

Berry, Wendell. Home Economics. New York: North Point Press, 1987. Sartre, Jean Paul. Jean-Paul Sartre: Basic Writings, edited by Stephen Priest. London, and New York: Routledge, 2001. Linssen, Robert. Living Zen. 1958. New York: Grove Press, 1988. Emerson, Ralph Waldo. The Spiritual Emerson, edited by David M. Robinson. Boston: Beacon Press, 2003. Berry, Wendell. Collected Poems: 1957-1982. 1985. New York: North Point Press, 1987.Daniel Garrett is a writer of journalism, fiction, and poetry. His work has appeared in The African, AIM/America’s Intercultural Magazine, AllAboutJazz.com, AltRap.com, American Book Review, Art & Antiques, The Audubon Activist, Black American Literature Forum, Changing Men, The City Sun, Frictionmagazine.com, The Humanist, Hyphen, Identity Theory.com, Illuminations, Muse-Apprentice-Guild.com, Option, PopMatters.com, The Quarterly Black Review of Books, Rain Taxi, Red River Review, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, The St. Mark’s Poetry Project Newsletter, TechnologyReports.net, 24FramesPerSecond.com, UnlikelyStories.org, and World Literature Today. He says, “I recently saw the films Hero, We Don’t Live Here Anymore, Vanity Fair, Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, The Motorcycle Diaries, Kilometer Zero, and Stage Beauty??—I really liked ??Motorcycle Diaries and Stage Beauty. My film viewing occurred during a season when I also enjoyed, or remembered the pleasure of, Carl Hancock Rux’s concert in Central Park, Eva Cassidy’s albums (Songbird, Imagine, Live at Blues Alley), the Romare Bearden and Gilbert Stuart exhibits at the Metropolitan Museum, hearing and seeing Alan Hollinghurst read from his novel The Line of Beauty (it won the Booker prize shortly thereafter), listening to WBAI’s ‘Equal Time for Free Thought’ and Kiss-FM’s ‘Open Line’ radio programs, and reading some of Colin McGinn’s reviews in Minds and Bodies and all of Durrenmatt’s The Visit, a terrific play about cruelty and revenge. Huckabees remains near the top of that list.”