Forever Godard

Forever Mozart

What more can be said about JLG, Mr. Jean-Luc Godard (God-of-art?)? The patron iconoclast of cinema is showing no signs of slowing down in his old age (75) and, in fact, seems to continually rejuvenate himself through his art. Godard was always a vanguard artist who never rested very long in any one (head) space. From his early cinephilic Nouvelle Vague period (1959-1965), to his political awakening (1966-1968), to his dogmatic theory-meets-practice Dziga-Vertov period (1968-1972), to his experimentation with video in the mid-seventies, to his more philosophical and contemplative late period (post-1980), to his latest excursions into found footage meta-History with his ongoing Histoires du cinéma series. His later films, or more properly speaking ‘middle-period’ films, especially from Prénom: Carmen (1983) onward, show a definitive move away from the literary to the painterly, and in the process a move away from direct political textuality to broader humanist and at times spiritual concerns. One can even detect sly references to Andrei Tarkovsky’s later works in his 1990 Nouvelle Vague (the lateral tracking shots, the mute character (Alain Delon) and autumnal setting which recalls The Sacrifice, the appearance of Nostalghia actress Domiziani Giordano). Whereas early Godard was interested in questions of ideology, power, language, and secular materialism, his later works have become increasingly interested in the eternal mysteries of philosophy and metaphysics.

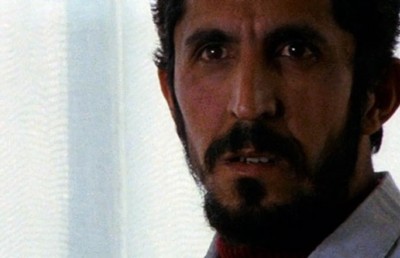

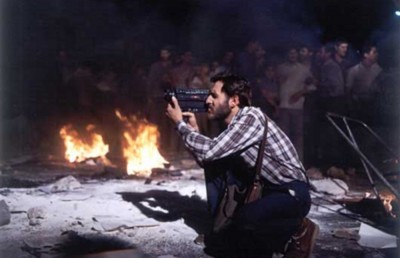

A voice-over narrator in Forever Mozart says, “film is a saturation of glorious signs.” Only now the semiotic system is less word-based and more image-based (many of the film’s interior shots can be mistaken for 17th and 18th century paintings). An exception being, perhaps, Allemagne 90 neuf zéro, with its many linguistic slogans and graffiti. In Forever Mozart Godard may be dealing explicitly with the civil war in Sarajevo, and references his own earlier anti-war tract Les Carabiniers (the middle hostage-taking sequence), but his real concern seems philosophical rather than directly social —as one character asks, “Is excessive evil worse than absent good?”.

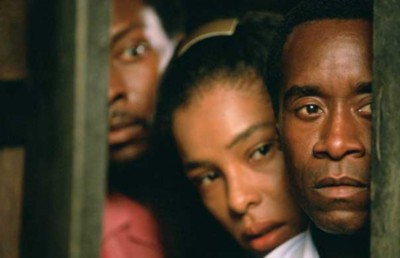

But Godard’s best films have always contained several levels of discourse. In fact, I (as others have) would suggest that Godard was the first genuine postmodern filmmaker, paralleling Andy Warhol in art, as the first filmmaker to consistently practice the art of pastiche (the mixing of high and popular art) and consistently and rigorously break down the “purity” of his/her art form. As in many earlier works, Forever Mozart gleefully references high art/culture (Albert Camus, Mozart, Alfred de Musset, René Descartes, and Jean Cocteau) and popular art (John Ford, Terminator). Intertextuality creates another level of discourse. In the opening scene two men are seen playing shadow soccer, a reference to the end of Michelangelo’s Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1967), where two people are playing shadow tennis. Godard recreates the shot from his own Alphaville (1965), a film which he had already revisited in 1991 with Allemagne 90 neuf zéro, of Lemmy Caution sitting at the side of a bed with a book in his hand. The situation of the film-within-a-film (Fatal Bolero) recalls Wim Wenders’ The State of Things (1982).

With Forever Mozart Godard shows us once again his wonderful ability to fuse art and life, and at times specifically his art and his life. Godard does it with both the film’s title and the title of the film-within-a-film (Fatal Bolero). The film’s central metaphor –a satire on U.S. military-speak– is “ war-as-classical music.” The players and “theatre” may change, but only as symphonic variations. This metaphor gives a faint apocalyptic feel to both the elliptical strains of classical music that bridge together scenes and the film’s title [“Forever War”]. To make the link between life and art blunt, Godard cuts immediately from the middle war sequence to the film-within-a-film set of Fatal Bolero. Such jarring scene or narrative changes may upset some audiences. But, to quote Robert Stam, Godard may be getting old, but he still remains “the obnoxiously charming provocateur.” And for this we should always be grateful.