Filmed Cities: Eden or Purgatory?

From Los Angeles to Athens

1.1. Introduction

“Every story is a travel story – a spatial practice” (Michel de Certeau 1984 in Giuliana Bruno 1997: 46).Every cinematic narrative requires, by definition, a space in which actions take place. According to Gardies (1993: 100-103), the cinematic narrative shows reality but narrates metaphorically, meaning that the moving image does not speak; yet it “says” and reveals important information. Therefore, the localization of things, people and places in a shot possesses a narrative dimension. What is shown here and now, takes its meaning in relation to the other shots that precede or follow. Hence, a total of strategic narrative rules define what is seen. In the article “Introduction à l’analyse structurale des récits” (1966), Roland Barthes distinguished two categories of narrative functions, Functions [1] and Indices. The indices proper relate to concepts such as character and atmosphere. We could easily conclude that the atmosphere of the narrative depends heavily on the choice of the space where the characters act. Therefore, Barthes’s tools can be of assistance in our filmic analysis as they facilitate the understanding of the semiotics of space and its narrative function.

The filmic space can serve the narrative in very significant ways, even taking part in the evolution of the plot, as cinema has the power to personify all inanimate objects. Even whole cities can be transformed into functional, dare we say, irreplaceable characters in the narrative. Many is the time that the city, the neighbourhood, or the apartment/home, the places in which the characters act, do not simply serve as background. For instance, in the Greek production Delivery (Nikos Panagiotopoulos, 2004), the urban setting of Athens is used in an active and profound way to illustrate and intensify the hero’s frustration and confusion. Allan Siegel (2003: 137) states that “the cinema provided the public with distinct images and ideas. In this context, and throughout its evolution, the cinema has influenced political, economic, and cultural reality and transformed our perception and reading of the urban environment.” In addition, “reading of filmic iconography presupposes the recognition of their production context, which adds productive questioning to research, problems that derive from genre theory. The conventions of each filmic genre (melodrama, comedy, musical, etc.) determine a specific context of reference as far as spatial depiction is concerned and provide the spatial representations of film with new connotations” (Milonaki 2005: 8).

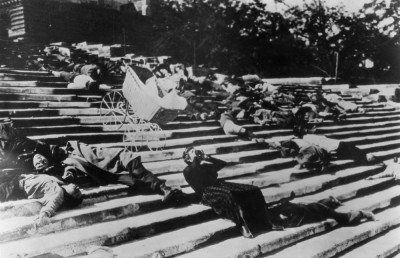

Even in the early days of the cinematic art, the city has been a constant presence, except for specific genres, such as the western, which preferred the bare and dangerous landscapes of the West. Ever since Metropolis (1926), the depiction of the city has had “two different levels; that of a clean, utopian city of lords, where their children play and celebrate carelessly, and on the other hand an underground (with every sense of the word) city of workers-slaves that serve their masters to the death (at least until the moment the robot Maria will lead them to rebellion)” (Nino Fenek Mikelidis, 2002: 18). The first cinematic attempts were fraught with innumerable images of the city and urban landscape [2] (Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: The Symphony of the Great City (1927), Germaine Dulac’s The Seashell and the Clergyman (1927), Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera (1928), Alexander Medvedkin’s New Moscow (1938), etc.). However, our paper aims at the contemporary depiction of the city and its various connotations expressed via a number of films.

1.2. How Does Modern Capitalism Affect the Ιmages of the City?

The 20th century is characterized by what a number of historians refer to as multinational capitalism [3] (Mark Shiel, 1993: 161-4), a capitalist expansion on a global scale.

This expansion is driven by a relative decline in the power of individual nation states as such and by a proportionate rise in the power and status of corporations and a newly emergent transactional capitalist class,… in a relatively small number of particular world cities which operate as command and control centers for corporate function and global reach…The historical development from market capitalism and classical realism to imperialist capitalism and modernism, to global capitalism and postmodernism, has always been easiest to apprehend on the ground as a spatial development – in the development of urban spaces as articulations of a current world system at a given moment in time, and… the development of particular cities over other cities as the articulation of the succession of one world system over another through time.

What Shiel (1993: 164) calls “the quintessential post-modern urban environment,” Los Angeles, appeared “with increasing frequency and self-confidence in Hollywood cinema after World War II.” [4] Some writers, such as Soti Triantafilou (1990: 29), consider Los Angeles as a non-city and similarly Southern California as just the end of a journey, a place that must be conquered from within. For numerous films that take place in L.A. (Into the Night, 1985, Pretty Woman, 1990, Last Action Hero, 1993, etc.), Triantafilou believes that the city watches itself complacently in the mirror and confirms its architectural exaggeration, or is transformed into a plain setting; in this way the films look at L.A. without any true love for the city. It has often been stated that L.A. has no depth, no third dimension, no real substance, that it is just an artificial city expanded with the help of the film industry whose heart it still remains.

I would not agree with this statement as there are numerous contemporary cinematic examples that refute the non-existence of L.A. Let us not forget that “the space of dramaturgy proves to be as determining as the choice of the story and the film’s protagonists as the plot unravels in a determined socio-spatial reality of the heroes, that is depicted realistically through the filmic images” (Milonaki 2005: 1). Based on this view as well as Gardies’ theoretical premise about the narrative dimension of filmic space, we will proceed by analyzing the spatial representation in two films set in L.A., Fight Club and Collateral.

1.2.1. Fight Club

In 1999 the director David Fincher shot Fight Club, a film that has been compared to Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) [5], mainly as far as its raw representation of violence is concerned. The film was shot in Los Angeles and Wilmington, an industrial neighborhood of L.A., and depicts a side of this megalopolis that has rarely been seen on the silver screen. What the audience sees is a bleak urban setting that has managed to dehumanise its inhabitants, along with the pressures imposed by the current capitalistic norms. The film’s hero, the narrator (Edward Norton), whose name we never learn, has not slept for six months. He works as a recall coordinator for a major automobile company and lives in a comfortable condo. In a revealing scene, which should be more disturbing than the fighting that takes place later in the film, the narrator is in his apartment, talking to the audience and confessing that “Like so many others, I have become a slave to the Ikea [6] nesting instinct,” while he is in the bathroom thumbing through an Ikea catalogue and ordering the item of his choice telephonically. He then walks through the rooms of his apartment filled with items bought over the phone. The director places superimposed tags on each piece of furniture with the intention of making the apartment look like a catalogue display, adding a social comment on the social mores of our times. The narrator goes on saying:

What kind of dining set defines me as a person? We used to read pornography. Now it was the Horchow collection. [7]

The scene is characteristic of the times we live in, at least, in Western societies. People are on course to potentially lose those traits that bestow upon them a sense of individuality. They are driven by an urge instilled by the media and its controllers to acquire material possessions in order to be defined as people of a certain status, as superior personalities.8 The narrator of Fight Club is leading a meaningless existence that becomes tolerable only through the purchase of material goods. He believes that his home is decorated to his taste when, in reality, his choices were manipulated by a well-organised global conspiracy. This is the main reason he cannot find comfort in the home he believes he created for himself. Later in the film, he finds solace by frequenting various support groups, as listening to the real pain inflicted upon others makes him feel calm and enables him to finally sleep. However, a woman disturbs his peace until he meets his alter ego, Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt), on a plane and moves on to establish a private group called the “Fight Club,” where men beat each other up in an effort to forget their mundane reality. After his meeting with Tyler, a terrible accident burns his precious condo to the ground. Fincher interjects a moment of irony when, as the narrator approaches his building, we glimpse the “Pearson Towers” and underneath the sign: a place to be somebody. Once again, the building, as well as the neighborhood, is used to describe not only the space in which the filmic action is taking place, but to comment on the social reality. Pearson Towers is not a simple residence. It is a place to be somebody, as if the walls and the rooms have the power to elevate their tenants’ social status.

The narrator calls up Tyler and they meet in a bar. Another revealing dialogue ensues:

Narrator: I had it all. Sofa, stereo, wardrobe. I was close to being complete. Tyler: We are consumers. We are by-products of a lifestyle obsession. Murder, crime do not concern me. What concerns me are celebrity magazines, TV with 500 channels, some guy’s name on my underwear. The things you own end up owning you.

The hero wants a place to sleep and Tyler offers to put him up. However, his house has nothing to do with what the narrator is accustomed to. Tyler lives in an isolated, dilapidated house on Paper Street. However, the narrator does not seem to mind as he quickly gets used to living without the comforts provided by the standard of his past hip lifestyle. As their Fight Club begins to have more and more members in its basement bar setting, Tyler explains where all this frustration and anger comes from:

Tyler: It’s not until we’ve lost everything that we are free to do anything. We’re the middle children of history. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No great Depression. Our Great war is a spiritual war. Our great depression is our lives. We’ve all been raised by TV and believed that one day we’ll be millionaires and rock stars. We’re not. We’re slowly learning that fact. And we’re very very pissed off.

This brief monologue encompasses the very essence of the film’s narrative which is cleverly revealed through the binary opposition between the narrator’s apartment and Tyler’s house. The opposition “comfortable condo vs. decrepit old house” is the foundation of the film’s premise, even if it is executed in a most exaggerated way. The cosy flat represents financial stability, hard work and uniformity, whereas the narrator’s rundown residence stands for the return to a simpler way of life, honesty and, more importantly, freedom from all the rules that modern society imposes on its subjects. That is why, according to Almar Haflidason (2000) [9], “Fight Club appears threatening to some because it seems to challenge the safety of the modern world.”

1.2.2. Collateral

In 2004, Michael Mann shot Collateral, a morbid tale of a contract killer (Tom Cruise) who hires a cab driver (Jamie Foxx) for a night in order to execute five different people in downtown Los Angeles. Behind this simple plot summary, the story is actually about the city. The director, who finds L.A. the most fascinating of contemporary American cities, thinks the movie is really about what you see out the windows of the taxi, the refineries in Wilmington, Koreatown, the architecture, the freeways. Mann [10] discusses his filmic intentions by stating the following:

L.A. is a unique city and when it’s humid, what happens is that all the sodium vapour from the streetlights, in this megalopolis of 17 million people, bounces up onto the bottom of the cloud layer, and it becomes a diffused light. You see this wondrous, abandoned landscape, with hills and trees and strange lighting patterns. It’s a very, very magical place and I wanted that to be the world that Vincent and Max (the two protagonists) are moving in. So then how much of that do we see? And the answer is, not a lot in film. And that’s why I moved into shooting about 90% of the picture in high-def, to see into the night. I remember driving north on Fairfax and stopping for a light, and these three coyotes just walked diagonally across the intersection, like they absolutely owned it. It wasn’t just the presence of wild animals in the middle of the city, but their attitude of, this is their domain.

Mann even incorporates a scene with the coyotes he mentions and no one, other than a true “connoisseur” of the city, could believe that this can happen in this megalopolis at the beginning of the 21st century. Collateral is filled with long aerial shots of the highways, the surface roads, the streets and the skyscrapers of Los Angeles. Even when the scene centres on the two protagonists (the taxi driver and the killer) in the confined space of a taxi, Mann has the buildings and the streets reflected onto the vehicle’s windows. Fascinated though the director may be by the city, he does not fail to acknowledge the cold and inhuman side of L.A. Vincent’s (the killer) words are a clear testament of Mann’s voice and opinion. In an early scene Vincent engages in small talk with Max (the taxi driver) and reveals his outlook on L.A. When asked if he has ever been in the city before, he replies:

Vincent: Tell you the truth, whenever I’m here I can’t wait to leave. It’s too sprawled out, disconnected. You know.

And a little later he elaborates on the above statement.

Vincent: Seventeen million people. If this was a country, it would be the fifth biggest economy in the world, and nobody knows each other. I read about this guy, gets on the MTA [11] here, dies. Six hours he’s riding the subway before anyone notices his corpse. Doing laps around L.A., people on and off sitting next to him. Nobody notices.

Vincent’s comments cannot go by unnoticed. The city has become so sprawled out that, as far as the film narrative is concerned, he can commit his murders without being caught, as no one is going to notice him (or his victim). On the other hand, his story about the dead man in the subway illustrates and confirms, in a most revealing manner, an opinion that transcends the cinematic narrative line and applies to sociological critique. Even if Vincent is just referring to an urban legend, the spectator cannot but acknowledge traces of the ugly truth. Long gone are the days when cities were filled with welcoming neighborhoods, where everyone was on first-name basis, relationships were born, and a sense of security and care hung in the air. Mann does not only comment on the social realities of Los Angeles; Vincent’s comments become a sign (and we use the term in its semiotic context) of modern times, referring and condemning at the same time the impersonal urban centers which do nothing but sprawl out vertically or horizontally and contribute to the complete alienation of their inhabitants.

As in Fight Club, we can easily distinguish some similarities, as far as the mood and the atmosphere of the city. Fincher and Mann’s L.A. converge on a depressing depiction of this megalopolis, which grows larger and more powerful by feasting on its residents, as if it were afraid of being threatened by them. In this way, L.A. reminds us of Kronos, the mythological ruler of the ancient world, who ate his children for fear of being dethroned by one of them.12 For instance, Max, the cab driver of Collateral, talks about starting his own business and insists that his current employment is just temporary, failing to mention that he has been doing it for the past twelve years. When Vincent confronts him, Max tries to defend himself by stating he needs a detailed plan and has to solve many bureaucratic issues before embarking on the career he has been dreaming of. The system of the city prevents him from fulfilling his vision. Driving on the innumerable streets of L.A., on the alert all the time to avoid the next traffic jam, leaves him little time to spend on his venture.

1.2.3. Delivery

From the huge Los Angeles we turn our attention to a contemporary European capital, Athens, a modern metropolis which has accumulated almost half the population of Greece, as well as a multitude of immigrant races. Athens is still considered the cradle of western civilisation, the place where democracy and culture was born. Its cinematic depiction reached its heyday during the golden age of the Greek cinema (1950-1960). [13] Barber (2002: 61) supports this:

In the decades after the Second World War, a primary preoccupation of European cinema was the slow-burning impact on cities and their inhabitants of that conflict’s residue… the architectural forms of its cities recoiled from the conflict in another way. Immense building programmes, often executed at high speed, replaces destroyed or damaged districts, configuring a pattern of endless concrete tenements that grew over the subsequent decades… forming the location for much of the vital urban film-making of that period.

The Athens of the 21st century presents many different facets. The Greek cinema of the 1950s and 1960s praised its integration into modern Western European city, with its new and functional blocks of flats, excepting the few neorealistic trails of Athenian slums. The Greek director Nikos Panagiotopoulos [14] decided in 2004 to shoot a film about the other side of Athens. Delivery was presented at the 61st Venice Film Festival and got mixed reviews. On the one hand, some critics praised the wonderful performance of the hero, the actor Thanos Samaras, and on the other hand, some were unsure of the director’s intention. However, most of the viewers, connoisseurs or not, failed to comprehend the film’s central narrative element: the city itself. As the director made clear at the press conference of the festival, Delivery is a film about the true city of Athens. Not the host of the 2004 Olympic Games, not the city of the big athletic constructions and the chic neighbourhoods of the north and south suburbs, but the modern metropolis which is filled with all the ugliness, drugs, violence, poverty, and dangers we want to hide and therefore decide to marginalize or ignore.

The nameless hero of the film is a young Greek man who arrives in Athens by bus on a hot summer night. The first scenes of the film are indicative of what is soon to follow. Immigrants that get off the bus, a crazy woman blowing a whistle while verbally attacking the travellers, and the dirty public water closets are the first pictures the hero encounters as he gets off the bus. Even though the first scenes are shot indoors, they still present pictures of Athens that the random tourist will rarely get a glimpse of. After a quick rest, the hero gets out of the station. The sequence that ensues reveals the other side of Athens. The director structures his hero’s first encounter with the megalopolis using four travelling shots. The first three, moving respectively to the left, the right and the left of the screen, show general shots of the streets, the buildings and the constructions that are taking place in the Olympic capital, and create a sense of commotion and disorientation, while the fourth travelling shot (once again to the right) moves across three phone booths, the first occupied by two immigrants from Russia, the next by two Africans and the third by a Greek middle-aged man who is probably unemployed and wants to talk to a member of his family who does not return his call. Then the camera stops moving and we see the hero moving about. A cut shows us three old men sitting on the pavement while two more cuts present a young man, probably a drug addict, sleeping on the street and a conversation between two pairs of junkies talking and standing on the same street. In the final scene of the sequence, the camera moves along with the hero, who is also trying to make out his surroundings and plan his next move. The sequence makes a powerful impression on the viewer, due to the director’s cinematic techniques. The first three travelling shots create a sense of fast rhythm appropriate to a modern capital such as Athens, while at the same time they reveal the ongoing changes that perpetually alter the urban landscape. The travelling shots along the phone booths reflect the new socio-political status of the modern metropolis. The Athens of the 21st century not only attracts Greeks from every part of the country; it also constitutes the ultimate goal of immigrant races from all over the world, as Paris or the cities of Germany were a few decades ago. The cuts to the marginalized people, the old and probably homeless men as well as the drug addicts, are static objective shots. The camera does not move, as if it tries to capture the essence of solitude and despair that has invaded the souls of these specific people. Thus, the director produces a contrast between the fast developing pace of the city and the slow-paced life some of its inhabitants are forced to lead due to lack of employment, money or proper standards of living.

The hero will start his effort to survive in this hostile environment which offers only a few rays of hope for improvement. He finds a job as a delivery boy in a pizza place and also love in the form of the only female employee, who also speaks as little as him. The film does not have a classical narrative drive, in the sense that there is no clear beginning, middle or end. The nameless hero has no clear purpose and his actions reveal no specific intentions. This is clearly the director’s doing as he shot a film about the city and not about characters. He fills his filmic text with images of the ugly side of Athens –ruined houses, run-down apartments, the Athenian Chinatown– and demonstrates that this urban landscape can affect people and lead to homelessness, substance abuse, violence, theft, and street begging. Human beings are reduced to objects as they struggle to provide themselves with their daily bread. However, Panagiotopoulos does not judge. He merely presents the images of the Athens no one wants to accept exist, especially during the Olympic year of 2004. He therefore succeeds in creating a film centred on a city, personifying its every ugly corner, knowing the audience reception would not be in his favour. At the same time, however, he manages to transcend the classic narrative boundaries and speak the truth which “is rarely pure and never simple.”

1.3. Conclusion

The cinematic scenes we analysed are characteristic of our modern times. The indices we encounter present a bleak atmosphere of the world metropolis which does not differ, whether Los Angeles or Athens. The urban settings of the three films are filled with uninviting neighbourhoods, derelict houses, impersonal and vast streets, places which affect the psyche of the people who reside in them. Each film’s space is carefully chosen and reflects the heroes’ boredom, anger, misery, increasing violence and agony. Each film’s space, then, is part of the narrative structure and plays as important a role as do the events of the story. Therefore, a more detailed study of the role urban environment plays in the film world can reveal significant changes in the real world we inhabit. For example, the films analysed in this paper present the type of ugly settings we become blind to in order that we can get on with our lives. However, ignoring the truth cannot make the ugliness disappear. On the contrary, humanity’s indifference only contributes to the deterioration of the situation. Capitalism and globalisation only assist the expansion of the already huge urban centres, and film, which has always captured the ongoing great historical moments, does not fail us. The heroes of the films we discussed are trapped in the webs of the city and have to resort to drastic measures to free themselves. The representation of the films’ urban setting threatens our deceptive stability. In this way the filmic texts, which are inherently political, try to warn us of the catastrophic social consequences of urban expansion. The message has been sent and it is up to us to decode it and, most importantly, act on it.

Note: A shorter version of this article was presented in the 6th Crossroads Conference, 20-23 July, 2006, Istanbul, Turkey.

Filmography

Fight Club (1999). Dir. David Fincher. Production companies: Art Linson Productions, Fox 2000 Pictures, Regency Enterprises, Taurus Film. Script: Jim Uhls, based on the novel by Chuck Palahniuk. Cast: Edward Norton (The Narrator), Brad Pitt (Tyler Durden), Helena Bonham Carter (Marla Singer). Duration: 139 min.

Collateral (2004). Dir. Michael Mann. Production company: Dreamworks. Script: Stuart Beattie. Cast: Tom Cruise (Vincent), Jamie Foxx (Max), Javier Bardem (Felix), Jada Pinkett Smith (Annie). Duration: 119 min.

Delivery (2004). Dir. Nikos Panagiotopoulos. Production company: Graal S.A., Greek Film Center. Script: Nikos Panagiotopoulos, Michel Fais. Cast: Thanos Samaras, Alexia Kaltsiki.

Duration: 100 min.

City of Night: the making of Collateral (2004). Dir. Laura Davis. Production company: Dreamworks. Script: Jed Dannebaum. Duration: 41 min.

Bibliography

Filmed Cities. The City in Film and Literature. Kinimatographimenes Poleis. I Poli ston Kinimatografo kai ti logotexnia. Panhellenic Union of Film Critics. Athens: Patakis, 2002.

Barthes, Roland. “Introduction à l’analyse structurale des récits. » L’aventure sémiologique. Paris : Seuil. 1966. 1985. 167-206.

Bruno, Giuliana. “City Views. The Voyage of Film Images.” The Cinematic City. Ed. Clarke, David B. UK: Routledge, 1997. 46-58.

Gardies, André. Le récit filmique. Paris: Hachette, 1993.

McFarlane, Brian. Novel to Film. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

Metz, Christian. Film Language. A Semiotics of the Cinema. Trans. Michael Taylor. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

Milonaki, Aggeliki I. Representations of urban space in Greek cinema (1950- 1970). Unpublished Ph.D. Dpt of Journalism & Mass Media. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. 2005.

Shiel, Mark. “A Nostalgia for Modernity: New York, Los Angeles, and American Cinema in the 1970s.” Screening the City (eds. Mark Shiel and Tony Fitzmaurice), London: Verso, 2003.

Siegel, Alan. “After the Sixties. Changing Paradigms in the Representation of Urban Space.” Screening the City (eds. Mark Shiel and Tony Fitzmaurice), London: Verso, 2003.

Soldatos, Giannis. History of the Greek Cinema. Volume 3. 1990-2002. Athens: Aigokeros, 2002.

Triantafillou, Soti. Filmed Cities. (Kinimatographimenes Poleis). Athens: Sigxroni Epoxi, 1990.

Electronic sources

Berardinelli, James. club1999review.shtml”>Review of Fight Club, dir. David Fincher. 14/10/2000. 25/05/2006.

Endnotes

1 The category of Functions include the sub-categories of cardinal functions and catalysts. The cardinal functions refer to significant events that are directly involved in the development of the plot, whereas the catalysts denote secondary events whose role, as Brian McFarlane states (1996: 14) is to “root the cardinal functions in a particular kind of reality, to enrich the texture of those functions.” The category of Indices includes the indices proper (to use the McFarlane translation) and the informants, that is names, ages, and professions of characters, etc.

2 “Throughout the first half of the 20th century, cities became transformed and even brought into existence through the impetus and movement of film images… The torn cities of revolutionary Europe at the end of the First World War, the industrial cities around the far edges of Siberia and the terminated locales of warfare in 1945 all became defined (and in some cases were invented) directly by the medium of the film image” (Stephen Barber 2002: 16-17).

3 Shiel (1993: 161) relies upon a historiographical model “which views Western history,… as the history of the development of capitalism through a series of three particular ‘stages’.” According to this model, the three stages of capitalism is classical market capitalism (15th century-turn of 19th century), succeeded by imperialism capitalism, that is the first age of modernity, and finally, multinational capitalism or late capitalism, or advanced capitalism, which came in the Sixties.

4 “This was a rise to prominence integrally related to the increasing post-industrialization of the US economy, and not coincidentally linked to the preponderance since the 1960s of presidential administrations with strong links to that part of the country –from Lyndon Johnson to Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, and, today, George Bush I and II –as suggested by Oliver Stone’s JFK (1993)” (Sale Kirkpatrick in Shiel 1993: 165).

5 See James Bernadelli’s 6 “Ikea is an international home furnishings retailer, well-known for its unique furniture which consumers are often required to assemble for themselves. The chain is famous for its functional yet stylish products, and has 231 stores in 33 countries” Wikipedia.

7 Samuel Roger Horchow was an American entrepreneur who in 1971 started The Horshow Collection, “the first luxury mail-order catalog that was not preceded by a brick-and-mortar presence” 8 Likewise, in American Psycho (Mary Harron, 2000), a black comedy with Hitchcockian overtones, the hero starts a series of atrocious murders just because his business card was not as glamorous as that of one of his colleagues.

9 See review of 10 Michael Mann Interview. City of night: the making of Collateral.” Davis, Laura, director. 2004. DVD. Dreamworks. 2004.

11 MTA stands for Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

12 Unfortunately for Kronos, his wife Rea gave birth to Zeus in secret, confirming Kronos’ anxiety, as Zeus overthrew his father in a ten-year battle and imprisoned him in the underworld, Tartarus.

13 Milonaki (2004: 168-170) notes that despite the technical improvements of this period, the look of the Greek film production of the period 1957-1961 abandons the urban outdoor space and focuses on the private space of the house or apartment, reflecting the modernization of the society.

14 Nikos Panagiotopoulos, one of the most respected and talented filmmakers in Greece, is “a brilliant bourgeois director,” according to Giannis Soldatos (2002: 263). His credits include films that are characterised by a personal style and a unique sense of humour. His subject matter is mainly the search for love, whereas the locations of his films differ considerably. From the streets of the Greek capital (The Bachelor, 1997), the decadent night clubs of the Greek countryside (The Edge of Night, 2000) to the cosmopolitan island of Mykonos, the perfect setting for the director’s sly comments on the decadence of the Greek nouveaux-riches in the farce Beautiful People (2001), Nikos Panagiotopoulos, an admirer and disciple of Jean-Luc Godard, manages to capture the subtle nuances of the Greek spirit, even at its most depressing and disturbing moments.