Remaining Men Together: Fight Club and the (Un)pleasures of Unreliable Narration

A Crisis in Masculinity

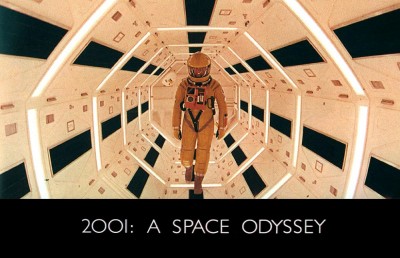

It seemed a strange thing when David Fincher’s film Fight Club appeared in multiplexes across the U.S. in October of 1999. Here was what appeared to be a very transgressive anti-consumerist film, financed and widely distributed by 20th Century Fox, one of the largest studios in Hollywood. An intriguing mix of action, dark comedy, and social commentary, Fight Club became a cult item, proving to be much more popular on video than it was at the box-office. [1] Perhaps the most striking aspect of the film is its revelation that the unnamed Narrator (Edward Norton) and his friend Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) are twin sides of a split personality. This sort of unreliable narration has become an increasingly common cinematic narrative strategy since the 1990’s. Because of its “mainstream” status, Fight Club stands as a key text in a developing narrational mode of cinema that radically departs from classical Hollywood narratives through the use of dramatic deception of the spectator––yet manages to straddle both art-house and mainstream acceptance. [2]

In the first part of this essay, I will attempt to define the general aspects of this narrational mode, and the mechanisms operating within the films that comprise it. These films share various normative qualities, such as extreme modes of character subjectivity (e.g., dreams, flashbacks, psychosis, etc.), a lack of narrative closure, and a dramatic manipulation of the spectator’s expectations that produces an enforced submission to the narrative. Following from the work of Gaylyn Studlar, I would like to argue that these unreliable narrative strategies result in an especially masochistic spectatorial pleasure that is in large part linked to the fundamentally masochistic diegeses of these films. Because of the way unreliable narratives use extreme subjectivity in order to tell their stories, identity becomes a very unstable concept on the diegetic level, reflecting not only the loss of identity/ego boundaries inherent in all cinematic spectatorship, but the loss of identity that is necessary to the special (un)pleasures created by the narrative strategies of these particular films.

In the second part of the essay, I will discuss the implications of these narratives’ diegetic masochistic qualities, featuring Fight Club as my primary example. I begin with thematic connections between film noirs, a series of films long associated with the displacement of men, and unreliable narratives, a more (post)modern series of texts which I believe echo similar concerns. In their masochistic portrayal of (predominantly) men with shattered identities and rampant paranoia, unreliable narratives appear to reflect the purported “crisis of masculinity” voiced by white, heterosexual, middle-class males during the 1990’s. While spectators of any gender can enjoy the masochistic spectatorial pleasures created by the formal qualities of these films, the diegetic content speaks more directly to the contemporary concerns of men. The act of reconstructing these fragmented narratives is a method of pleasurably recuperating a threatened sense of masculinity––but the lack of traditional closure in unreliable narratives can never fully resolve this personal sense of crisis for male spectators. Since the underlying structural concerns of these films continue to reflect an unresolved crisis, the narrational mode serves to effectively perpetuate male paranoia over a feared loss of patriarchal power. Though the seemingly subversive Fight Club tends toward a blatant bias in its treatment of gender, it is indicative of unreliable narratives in general, a group of films that can be read as more reactionary texts than they might appear to be upon the disorienting first viewing. Truly, if these films reinforce nothing else, it is the old cliché that appearances can be very deceiving.

I. Unreliable narratives as masochistic texts.

As a matter of preliminaries, several concepts need to be explained. The terms fabula and syuzhet, derived from Russian Formalism, refer to interlocking processes through which the act of narration is created. The fabula is the complete story that the reader (or, in this case, the spectator) of a text mentally constructs as an extension of the syuzhet, or the text itself; to put it another way, the fabula is the basic story, but the syuzhet is the way in which that story is told. The syuzhet is the specific arrangement of information and events (e.g., scenes in a film) which allow the spectator to construct the fabula. As David Bordwell says, “Any syuzhet selects what fabula events to present and combines them in particular ways. Selection creates gaps; combination creates composition.” [3] Gaps in the fabula are created by events or durations of time which are not included or explained by the syuzhet; these gaps may be temporary, to be explained later in the film, or left as permanent gaps (as is often the case in films with unreliable narration). The fabula will necessarily be more expansive than the syuzhet because what the syuzhet actually shows (moments at which the syuzhet and fabula overlap) is a condensed version of the most pertinent fabula events. For example, a film may take place during a week in a character’s life, but the syuzhet will select only enough moments from that time period to fit into the film’s running time; likewise, the syuzhet will often provide expository information allowing spectators to extend their mental construction of the fabula to include past events in a character’s life that are not explicitly included in the film.

Though it may be argued that the spectator is a passive receiver of images, there are active cognitive processes at work in order to make sense of those images. The spectator is engaged in using “schemata and incoming cues to make assumptions, draw inferences about current story events, and frame and test hypotheses about prior and upcoming events.” [4] While the syuzhet itself provides text-specific cues, the spectator also brings sets of schemata (based upon past viewing experiences), such as familiar story patterns and generic conventions, to the text as a means of constructing viable hypotheses about what is being shown. “Our normal syuzhet, then, reduces to a demand for enough information for the construction of a fabula according to conventions of genre and mode,” says Bordwell. [5]

Unreliable narrative films, however, self-consciously subvert hypotheses and schemata derived from traditional narrational modes. They occupy a strange borderland between mainstream Hollywood cinema and art cinema––though tending to lean more heavily toward the latter in terms of formal style. Unreliable narrative films have had a number of historical antecedents [6], but it was not until the early 1990’s that this style of film began proliferating dramatically. Unreliable narratives have emerged in virtually every currently active genre (and often mix genres) [7], and in films from very diverse areas of the world. [8]

Because the primary structural similarity between these rather disparate films is based more explicitly upon the formal style of the narration than the content, these films are often associated more with individual directors/writers (e.g., David Lynch, Charlie Kaufman, M. Night Shyamalan) than perceived as comprising a genre in itself. Spectators create schemata based upon prior films by those individuals and may begin to anticipate the unreliability of narration as a guiding factor in consuming later films (e.g., Shyamalan’s “twist” endings that have come to be expected by the public). However, this sort of auteurist method of reading of films by specific writers/directors does not necessarily extend to the larger category of unreliable narrative films in general. Rather, there are various norms––primarily in opposition to the norms of classical Hollywood cinema––that apply to unreliable narratives and help to nominate them as an emerging narrational mode of their own. Bordwell defines a narrational mode as “a historically distinct set of norms of narrational construction and comprehension.” Unreliable narratives fit this definition, as they also “transcend genres, schools, movements, and entire national cinemas.” [9]

Unreliable narrative films as a mode have many norms similar to art-film narration, but utilize these norms to a much greater degree. Easily the most important norm of unreliable narratives is the extreme subjectivity through which the syuzhet is presented, often in the form of flashbacks, dreams, or hallucinations. Unlike classical Hollywood narratives, unreliable narratives do not often mark the boundaries between “objective diegetic reality” and “characters’ mental states”; while Bordwell notes that art-film narration is known for blurring these boundaries [10], I contend that unreliable narratives must do so to a much greater extent in order to preserve the mysteries of the text. This is clearly the case in Fight Club, which is presented almost entirely in flashbacks from a point in the fabula at which the Narrator knows that he has a split personality––but that crucial fact is not revealed to the spectator until the point in the flashback (the so-called “change-over”) where the Narrator learned it himself. While the syuzhet in classical Hollywood narration strives to communicate fabula information to the spectator and thus leave few permanent gaps, the syuzhet of an art-film calls attention to itself by restricting information and leaving more permanent gaps in the fabula, often resulting in endings that resist narrative closure. [11] This norm must be exercised more extremely in unreliable narratives in order to preserve the narration’s unreliability by concealing the type of subjectivity from which the syuzhet originates; indeed, more complicated films of this mode will have endings which leave the entire fabula up to interpretation. Bordwell observes that the classic text ultimately reveals all of its secrets to the viewer (even in the classical Hollywood mystery film), finally allowing comprehension of the fabula’s “absolute truth.” [12] However, I must emphasize that unreliable narratives never reveal a sense of “absolute truth.” The type of subjectivity producing the unreliable narration may be revealed to the spectator (e.g., the split personality in Fight Club) or it may remain ambiguous (e.g., the split personality in Lost Highway [David Lynch, US, 1997]), but there will always remain a lack of narrative closure due to a lingering distrust of the manipulating text. As Edward Branigan points out, “No matter how ‘objective’ and final the narration seems, it could be the result of any one of many implicit narrations that might be imagined one [narrational] level higher. Hence there will always be a measure of uncertainty about what is being depicted.” [13] He continues that “Levels of the narration may be structured to create unusual effects because they mark differing epistemological domains which may be complimentary or opposed.” [14] In my opinion, these sorts of “unusual effects” are a trademark of unreliable narratives by radically casting doubt over everything provided to us by the syuzhet. [15]

“What is rare in the classical film [is]…the use of narration to make us jump to invalid conclusions,” Bordwell says. [16] However, that is precisely the object of the syuzhet tactics employed in unreliable narratives. These films mislead the spectator into making hypotheses which are then shattered at a later point in the film’s duration, requiring an active effort by the spectator to reconstruct the fragmented fabula—but the fresh hypotheses which result are just as routinely shattered in the films in question. This repeated inability to accurately judge the “truth” of the text disorientates the spectator, resulting in a state of enforced passivity to the unreliable narrative. Disorientation can occur within the scope of a single shot (e.g., through a misleading POV shot), specific pieces of the syuzhet (e.g., scenes which seem to contradict others), or the film as a whole. However, these films must also provide enough cues for the spectator to continue attempting fabula reconstruction. If these cues are not given, the spectator will become irretrievably lost within the convoluted narrative and give up on the film. [17]

Accessibility to unreliable narratives is also worth noting in relation to the production and distribution of these films. Many are produced outside of the Hollywood studio system and become relegated to distribution in independent art house theatres. Not surprisingly, these tend to feature increasingly complicated syuzhet structures and more open, ambiguous endings than their Hollywood kin. The unreliable narratives which are most often backed by major studios (the presence of a major star notwithstanding) tend toward a “twist” ending or revelation that changes the perceived “reality” of what has hitherto seemed to be a more or less straightforward fabula (e.g., The Sixth Sense or The Others). After the “twist” in these films, the “true” fabula is often partly reconstructed within the diegesis itself as the characters briefly flash back (often in a montage) to moments from earlier in the syuzhet. Because these moments often appear different when seen through the lens of the reality-shaking knowledge provided by the “twist,” this flashback process provides spectators with images with which they too can make sense of what has already been presented by the syuzhet. In Fight Club, for example, during the revelatory conversation as the Narrator realizes that he and Tyler are the same person, there is a brief montage as he thinks back to various moments in the syuzhet at which he is suddenly standing in for the invented Tyler persona, doing things that he had always imagined Tyler doing. These twist endings in major-studio films may partially clarify to the spectator how he/she has been misled, but they ultimately lack the sense of “absolute truth” associated with closed Hollywood endings. Only a sense of semi-closure––made all the more false in light of how the spectator has been manipulated throughout the film—is reached that makes the film seem more coherent than the more ambiguously open endings found in various non-Hollywood films (e.g., Mulholland Drive, Spider), in which cues to assist in reconstructing the fabula are not given, resulting in enough permanent gaps about crucial fabula events that the story can only be reconstructed via careful interpretation.

Using Gaylyn Studlar’s theorizing of masochism as a primary spectatorial pleasure in cinema, my assertion is that unreliable narrative films are an especially masochistic form of text on both a spectatorial and diegetic level. However, I must first lay the groundwork of my argument by summarizing Studlar’s theory. Jean-Louis Baudry describes the cinematic apparatus as producing a “forced immobility” of the spectator during which the movie screen acts as a substitute for the “dream screen” (which originates during the oral stage of development, as the infant dreams upon the mother’s breast) on which the dreamer projects images. Cinema then produces a “more-than-real” sense of reality which mimics dreams and allows for regressive, narcissistic pleasures that originated during the oral stage, including the loss of body limits and ego differentiation. [18] Studlar uses Baudry’s premise to theorize that spectatorial pleasure is essentially masochistic since, in a dreamlike state, the spectator subconsciously associates the screen with the powerful oral (or pre-Oedipal) mother as a symbol of plentitude. One of the great strengths of Studlar’s theory (stemming from its basis in Deleuzean psychoanalysis and object-relations theory) is that spectatorial pleasure is “not limited to the male spectator” and can be enjoyed by anyone, regardless of gender. [19] This is because oral pleasures develop from the pre-Oedipal phase of development, in which castration anxiety does not factor and woman is still seen positively as plentitude (instead of negatively as lack, a sense eventually imposed upon her by the patriarchy in order to “consolidate its own power” by defining her as Other). [20] Studlar links the oral mother to unpleasure via the threat the mother poses to the infant’s survival by being able to control access to the breast, which the narcissistic infant always wants. [21] While nursing, the infant sees him/herself as undifferentiated in body (and ego) boundaries from the powerful oral mother, and thus the mother symbolizes everything to the child, while the father figure (or superego) serves only to come between mother and child; therefore, the child assumes a bisexual identification with the mother and only assumes the symbolic role of the father (represented by genital likeness in the case of males) in order to reject phallic sexuality by suspending orgasmic gratification. [22] The masochist, like the infant, desires reunification with the oral mother, defying patriarchal superego norms against bisexual identification, non-procreative sexuality, and pleasure in submission. [23] However, that symbiotic reunion is physically impossible, and death, as a complete obliteration of ego, becomes the only fantasy solution to masochistic desire: a fatal state symbolizing final defeat of the father/superego and reunion/rebirth from the oral mother as a nonsexual person who defines self in relation to the powerful female. [24] In its emphasis on submission to the “cold” female, the masochistic aesthetic depends upon fantasy, distance, suspense, and fetishistic repetition––continually disavowing reality, defying classical narrative causality/closure, and prolonging unpleasure through deferral of satisfaction. [25]

Studlar notes that all cinematic texts, even those that are not masochistic on a diegetic level (e.g., male characters whose masculinity is not threatened by submission to females), employ masochism as a spectatorial pleasure. [26] As she explains,

The apparatus provides the grounding that permits multiple partial, shifting, ambivalent identifications. This process defies the rigid superego control expressed in patriarchal society’s standards for carefully defined sex roles and gender identification and points to the importance of bisexuality and a mobile cathexis of desire in understanding cinematic spectatorship. [27]

As in the oral infant’s relationship with the mother, ego boundaries are lost during the viewing experience, but this “frightening loss of control” is made less threatening by its association with the bliss of maternal plentitude. [28] By entering the theatre, the spectator effectively enters into a contract with the film, surrendering control over the fantasy and over his/her own gender identification; “a measure of illusionary ego control” over the fantasies is retained by the spectator, but only through the ability to disavow that the dreamlike fantasies are real, thereby allowing the contract to be broken by walking out. [29] In the darkened theatre, the spectator is positioned as “passive receiving object and active perceiving subject. As subject, the spectator must comprehend the images, must give them coherence, but the spectator cannot control the images, just as the nursing child cannot control the mother.” [30] This unpleasure in the inability to control images is rooted in the primal scene, the infant’s inability to control the father’s sexual interference with the mother. [31] That said, it is important to note that, in the masochistic scenario, the desire for actual suffering may be secondary to the desire to be passive, dependent, and submissive. [32]

Returning to my argument, if cinematic spectatorship in general can be considered masochistic, then unreliable narratives produce especially perverse unpleasures. The defining features of unreliable narratives distinguish them as a type of masochistic narrative fitting Studlar’s theories, so it is my contention that the psychic processes described by Studlar also apply directly to unreliable narratives. Just as Studlar says that the diegetic subject matter of the masochistic text (“disavowal, suspension, fantasy, fetishism”) also becomes its formal qualities [33], I would note that the form of an unreliable narrative film’s syuzhet must inherently be a reflection of the source of subjectivity (e.g., dreams, memory, fantasy) used within the diegesis. As I will continue to explain, these films foreground masochism on both a spectatorial and diegetic level, clearly reminiscent of the masochistic texts described by Studlar. While Bordwell notes that classical Hollywood narration generates satisfaction by fulfilling the spectator’s hypotheses [34], unreliable narration creates pleasure by shattering hypotheses and delaying satisfaction indefinitely through permanent gaps in the fabula and open endings. Studlar writes that classical Hollywood closure restores patriarchal order and results in the fulfillment of an Oedipal (heterosexual) trajectory toward family formation, but masochistic narratives [including unreliable narratives, I would argue] defy this sort of closure by suspending fantasy indefinitely, breaking the illusion of reality created by the cause/effect flow of classical narratives. [35] The spectator endures the spectatorial unpleasure associated with classical narratives (and cinematic spectatorship overall) because he/she knows that the plot predicaments will eventually be resolved, resulting in the pleasures of narrative closure [36], but the absence of closure in masochistic narratives “marks a fetishistic return to the point of loss [of the oral mother].” [37] Just as the cinematic apparatus cannot manifest real objects, a text––but especially an open-ended text that denies the pleasure of narrative resolution––cannot actually reunite the spectator with the oral mother, and the disavowal of separation from her must end with the film as ego boundaries are restored. [38]

Though it could be argued that a self-conscious mode like unreliable narration has a Brechtian alienating effect upon the spectator, Steven Shaviro points out that narrative devices which violate conventional causal logic and temporality actually serve to please spectators all the more since

Brechtian techniques have an entirely different impact when they are transferred from the stage to the screen. The fact is that distancing and alienation-effects serve not to dispel but only to intensify the captivating power of cinematic spectacle. Precisely because film is…already an “alienated” art [due to its simulacral quality in both image and sound], its capacity to affect the spectator is not perturbed by any additional measure of alienation. […] Alienation-effects are already in secret accord with the basic antitheatricality of cinematic presentation. [39]

Spectators enjoy being mislead, being dominated by a narrative that provokes bursts of unpleasure by repeatedly shattering expectations. A masochistic narrative’s illusion of diegetic reality announces itself as a performance through “disavowing acts of memory and imagination” that fuse together past, present, and future, reflecting “the masochistic ‘art of fantasy’” [40], much in the way that unreliable narratives violate temporal continuity to pleasurably expose the workings of the deceptive syuzhet. According to Studlar, the suspension of reality is necessary in the masochistic scenario in order to disavow separation from the oral mother, but the superego threatens to shatter the oral fantasy by exposing that separation [41]; likewise, unreliable narratives must not provide too many cues and expose the narrative’s unreliability until the proper moment (if they do at all), since in a masochistic text “suspension of meaning becomes the narrative equivalent to the masochistic suspension of pleasure.” [42] For characters in masochistic texts to reveal their true emotions or intentions [or, for the sake of my argument, their means of subjective focalization in unreliable narratives] would end the narrative’s suspense and move toward gratification, instead of suffering. [43] Like the masochistic subject, the film spectator “is not permitted the control of knowledge,” says Studlar [44], and in unreliable narratives the spectator is forced to submit to a carefully controlled flow of cues within the syuzhet, as mentioned earlier. Much like the game of fort/da described by Studlar as mimicking the repetition of desire entailed in the union/separation of the oral infant and the breast [45], these cues help the spectator of the unreliable narrative construct the fabula, keeping him/her involved in the film––but the source of subjectivity in unreliable narratives must be carefully concealed to preserve the ambiguities of the text, either through contradictory cues (to shatter hypotheses about the fabula) or a shortage of cues. If this careful balance between revelation/concealment is not kept, the spectator may discover too soon how the narration is unreliable and thus feel a superior sense of satisfaction over the text (when cues are too numerous), or he/she may disengage from the film by feeling too much discomfort (when cues are too few, as in the earlier example of Last Year at Marienbad, a film that Studlar says “seems to consciously play on many conventions and situations that might be considered characteristic of a masochistic text.” [46]) Also like a game of fort/da, the extensive use of flashbacks and repetition of scenes in masochistic texts serves to freeze the narrative, making past and future simultaneous, since the “anticipation of pain and suspension of orgasm creates a paradoxical ontological present that ignores the objective boundaries of linear time.” [47] I would also apply this to unreliable narratives; for example, when a character flashes back to various fabula events after a “twist” in the syuzhet, the difference in how those events are perceived in hindsight allows for the character to masochistically replay the scene on a different level, in a different role—which is what flashbacks and repeated scenes allow in Studlar’s masochistic texts.

The loss of ego boundaries she describes is a particularly marked effect of unreliable narratives due to the unstable sense of reality created by focalizing a story so subjectively. Although Studlar says that oral spectatorial pleasure does not depend upon “conscious identification with a character” [48], diegetic masochism is certainly a norm shared by the films comprising this mode, due in large part to their emphasis on extreme subjectivity and insecure identities. The identities of the predominantly male protagonists in these films are often splintered or fragile via mental processes like memory, dreams, or even psychosis (e.g., Fight Club). This is not surprising, given Studlar’s assertion that symbiosis with the oral mother cannot be achieved “except beyond reality––in madness, death, or fantasy.” [49] Especially telling is her remark that “Like the film spectator suspended in a kind of waking hypnosis, characters in the masochistic text are often not quite sure if they are awake or asleep, perceiving or fantasizing into dream.” [50] Since texts creating characters with “fragmented and transformational psychic identities” produce a liberating dissolution of ego boundaries, Studlar argues that because the cinematic apparatus is already so adept at producing mobile, fragmented identifications, masochistic narratives “may be the most cinematic of all texts” [51]—and this quality, I think, is also the great strength of unreliable narratives in their ability to exploit the fluidity of identification by making cinematic images all the more treacherous. The almost exclusively male protagonists through which the films are subjectively focalized can hardly be said to resemble the sort of “ideal ego” found in classical Hollywood narratives according to the hypotheses of Lacanian film theory. Instead, these men suffer from unstable, radically shifting identities, manifesting paranoia and hysteria due to an inability to make sense of their own world. This lack of ontological knowledge/control is often reflected by a lack of sexual knowledge/control over a femme fatale character, or a loss of other traditionally masculine qualities. [52] As such, the diegetic masochism of these films serves to decenter traditional masculinity, defying a sense of wholeness and power, deferring indefinitely a sense of narrative closure that would help restabilize both the male protagonist and the male spectator. Interestingly, female filmmakers have by and large not utilized unreliable narratives in feature films (with the rare exceptions, such as Mary Lambert’s Siesta [US, 1987], or Mary Harron’s American Psycho [US, 2000]), though the narrational mode could conceivably open a political space within which to use the underlying masochistic aesthetic to subvert the traditional Oedipal trajectory of classical narratives in quite a different way from the feminist anti-narrative films of the 1970’s. One reason for this may be that unreliable narratives indirectly speak to a sense of threatened masculinity; although conscious identification with a character is not required by a masochistic text, for male spectators of these films, it may be a dramatic identification due to the general sense of crisis that abounds in representations of masculinity within this quite contemporary narrational mode.

II. Unreliable narratives as texts of crisis.

Since Bordwell says that “Accepting a historical basis for narrational norms requires recognizing that every mode of narration is tied to a mode of film production and reception” [53], then the emergence of this narrational mode during the 1990’s appears to be a reflection of the purported “crisis of masculinity” which Martin Fradley says “reached its zenith in the 1990’s” and certainly continues to this day as “one of the master narratives in post-1960’s American culture.” [54] The supposed crisis rose out of the “liberation era” of the 1960’s and 1970’s as a reaction against the displacement of white, heterosexual (middle-class) men in a culture in which feminism, civil rights, and gay liberation directly challenged the old order. To distance themselves from being seen as enemies in this culture increasingly hostile toward patriarchal power, men claimed that their own loss of a viable identity left them as victims. As Sally Robinson explains:

Like the dominant model of (male) sexual pleasure as based on building tension and the relief of discharge, so too do representations of crisis draw on the image of a pent-up force seeking relief through release. As this analogy suggests, the language of blockage and release (and the language of crisis and resolution) invokes a bodily economy and helps to explain, at least in part, the centrality of the white male body to explorations of crisis. But the release that men seek, and the release that might be found at the end of a crisis, are always deferred, and this is why we might say, following Gaylyn Studlar, that an aesthetic of masochism rules representations of dominant masculinity in crisis in the post-sixties era. [55]

Robinson finds a parallel between “the psychic economy of masochistic desire” and “the narrative economy of ‘crisis’ evident in individual texts and in the larger cultural landscape,” with masochism’s sense of a lost original plentitude corresponding in fictions of crisis to the same “illusory ‘true’ masculinity whose apparent decline motivates and fuels the crisis.” [56] As Fradley notes, these sorts of masochistic texts, representing a paranoid crisis of masculinity, have increasingly manifested themselves in contemporary Hollywood depictions of masculinity since the 1990’s, especially becoming a “key trope” in the traditionally male-oriented action genre (to which Fight Club belongs) [57]. It is in this light that I wish to look at the unreliable narrational mode as a reflection of that crisis––a crisis that is not limited to mainstream Hollywood films, but rather, like narrational norms themselves, can be said to transcend genres, schools, movements, and entire national cinemas in this post-liberation era. The crisis is “supposed to have affected men in all parts of the Western world,” but is “usually seen as especially pertinent in the U.S. because of that country’s (supposed) historical investment in masculinist individualism.” [58] Just as unreliable narratives continue to proliferate in contemporary cinema, in both art-house and mainstream films, the crisis of masculinity has not ended, and presumably will not cease in the near future.

If it is true that a crisis of masculinity is indeed represented as an underlying structural element of this narrational mode, then following structural genre theory, it could be argued that these films act as processes through which a sense of threatened masculinity attempts to be resolved––but this resolution is of course impossible given the lack of complete narrative closure characteristic of this mode––and therefore unreliable narratives will continue to propagate throughout contemporary cinema as an echo of patriarchal anguish. [59] It is especially in this respect that unreliable narratives bear an important resemblance to film noir (e.g., a handful of them even make allusions to Vertigo, a noir predecessor to the mode). Despite the fact that film noirs reveal their plot secrets at the end, they only create a sense of narrative semi-closure because the fabula is often too convoluted for the (male) protagonist to have pieced together on his own and doubt still lingers; this unresolved anxiety allows for underlying generic processes to continue in subsequent film noirs. Though many unreliable narratives (e.g., Lynch’s films) share iconographic elements with film noir (the most important being the femme fatale), both film styles use highly subjective, self-conscious narration (often featuring flashbacks, memories, or dreams) to examine themes of investigation, paranoia, doubling, masochism, and amoral violence. While it has been argued that characteristic noir elements such as flashbacks and voice-over narration are generic conventions that distance spectators from the confusion of the protagonists [60], unreliable narrative films do not permit that distance because they inject a noir ish (in)sensibility into disparate (or mixed) genres in which fabula information is not traditionally suppressed by the syuzhet (as it is in film noir and crime films in general). My point here is that it seems more than mere coincidence that such notable similarities exist between film noir and unreliable narrative films in terms of syuzhet tactics, themes, and iconography. The unreliable narrational mode blossomed during the height of a crisis bemoaning the displacement of men and a threatened masculinity––just as film noir (in which threats to the male protagonist’s safety are often read as threats to his sexual authority) is widely understood as a reflection of an earlier crisis of masculinity following World War II. The influence of film noir as kindred texts of crisis is less surprising given what Fradley calls the current crisis’s “powerful nostalgia for a prelapsarian homosocial economy of white male centrality…accompanied by a mourning and/or longing for a ‘lost,’ mythic national wholeness and plentitude” [61] commonly associated with the 1940’s and 1950’s, the same period in which the masochistic narratives of film noir subtextually voiced their fears of male disempowerment.

Now I would like to turn to Fight Club specifically, a film that Fradley says is (alongside Joel Schumacher’s Falling Down [US, 1993]) “probably the most explicit cinematic take on the much-vaunted ‘crisis of masculinity’ in post-industrial American culture.” [62] It takes the ideological stance that, in a post-liberation culture opposed to male empowerment or rites of manhood, men must still exert hegemonic power within a patriarchal system, using as little real outward violence as possible, but without losing their traditionally masculine attributes or a male-oriented vision of the future. With this conservative viewpoint, Fight Club raises its anxieties from the subtext and puts them on full display with masochism as its overt subject matter. No surprise then, when Robinson claims that “Masochistic narratives, structured so as to defer closure or resolution, often feature white men displaying their wounds as evidence of disempowerment, and finding pleasure in explorations of pain.” [63] The Narrator in Fight Club is a single middle-class white man who, in the absence of a strong father figure, was never initiated into the ways of traditional phallic manhood. During his adult years, he fails to find self-fulfillment in vainly surrounding himself with the superficial material possessions prescribed by American consumer culture; this lack of fulfillment, springing from the film’s equating of consumerism with femininity, results in his chronic insomnia. He discovers that by visiting support groups in search of a collective sense of pain, he can find an emotional release that allows him to sleep again. However, because this pain is not grounded in a recuperation of a traditional (even primal) masculinity, and with his sense of reality already affected by the bouts of insomnia, he develops a split personality that manifests itself as Tyler Durden, the hypermasculine, anarchistic id to the Narrator’s feminized, consumerist ego. Under the film’s logic, society as superego may still be a patriarchal system, but it is a patriarchy that since the liberation era has replaced its masculine attributes with feminine ones, creating a disempowered “generation of men raised by women,” a generation that has no Great War or Great Depression in which to prove one’s manhood (unlike the romanticized males of the 1940’s and 1950’s). As Alexandra Juhasz says, “In this late-1990’s dystopia, having a penis does not insure masculinity or even what masculinity used to shore up: power.” [64] In order to counter the effects of feminization by consumerism, the Narrator (believing that Tyler is a separate combatant) begins beating himself up and eventually creates Fight Club so that his fellow “slaves with white collars” will be able to experience the liberating power of their own masculine violence. But even when the Narrator is fighting others, he is still beating himself in the sense that they are all Everymen with a common drive for remasculinization—an image driven home later in the film when the nameless combatants shave their heads to become identical troops in Tyler’s private army, “Project Mayhem.” Fighting becomes a (self-destructive) method of self-discovery that frees men from the feminine vanity of self-improvement in gyms. This is a world in which emasculation is a fate worse than death––as the film makes evident through numerous references to castration as the worst possible loss, such as the support group for testicular cancer survivors (“Remaining Men Together”) at which the Narrator first discovers an intimate emotional release in exploring the pains of feminization––but even the emasculated Bob with “bitch-tits” (Meat Loaf Aday) is able to reaffirm his masculinity through the violence of Fight Club.

This male-on-male violence reflects the implicit homosexuality in the “Ozzie and Harriet” relationship between Tyler and the Narrator. As Stacy Thompson observes, “for gay sexuality, framed as a form of intimacy, violence is substituted, with each fight cathected for its participants and concluding with an embrace. In a conventional Hollywood homophobic staging of homosocial and homoerotic desire, men can touch each other intimately only with their fists.” [65] According to Henry A. Giroux and Imre Szeman, “The libidinal economy of repression…rearticulates the male body away from the visceral experiences of pain, coercion, and violence to the more ‘feminized’ notions of empathy, compassion, and trust”—and thus the film’s vision of masochism-as-liberation must celebrate the brutality of masculinity by misogynistically opposing femininity/consumerism. [66] Returning to my Studlar-influenced analysis of the film, the move toward homophobia and misogyny remarked upon by these critics seems regrettably necessary under the film’s logic in order to avoid a contradiction between a) the film’s political position toward remasculinization (taking masculinity as the lost plenitude), and b) the bisexual identification associated with masochism (wherein the child identifies with the feminine oral mother by taking her as the lost plentitude), which is manifested as homoeroticism in the film. We are told from the start that Marla (Helena Bonham Carter), the femme fatale described by Tyler as “a predator posing as a house pet,” has something to do with Project Mayhem’s planned revolution––the fabula thus revolving around an enigmatic woman in true noir fashion––and we learn that her interference in the Narrator’s tour of support groups is what inspires his Tyler persona to create Fight Club in the first place (since her presence as a fellow “tourist” at the groups spoils the emotional release required by the Narrator to curb his insomnia). As Thompson points out, Marla functions in the film as “a narrative necessity to satisfy the Hollywood aesthetic: the creation of a heterosexual couple,” first with Tyler, then with the Narrator at the end. For most of the film the Narrator would rather die than fuck Marla, only “sport fucking” her as Tyler, an act that Thompson considers a parodic portrayal of heterosexuality. [67] However, despite Tyler’s use of Marla as a sexual object, I would argue that, consistent with her role as femme fatale, she retains control and awareness of how she is being used. [68] In both implications, the Narrator is considered weaker than either Tyler or Marla, since throughout most of the film, Marla appears as a stronger character than the Narrator, able to control nearly any situation that he presents her with. As Studlar says of masochistic texts, the femme fatale acts to control and humiliate the superego role that is assumed by the male protagonist in order to reject phallic sexuality [69]; just as the Narrator, accustomed to superego-defined norms of heterosexual romance (e.g., love as a prerequisite for sex), cannot understand the parody of heterosexuality in Marla’s relationship with Tyler (representing the traditionally phallic qualities of the femme fatale), his own understood relationship with her is entirely nonsexual. It is important to note that, in masochism, bad mother traits (e.g., the phallic or intrauterine mother) are projected onto the oral mother and idealized, so phallic qualities of the femme fatale (e.g., emphasized by Marla’s possession of a dildo, or disembodied phallus) can be present within a masochistic text. [70] Likewise, says Studlar, fantasies from other developmental stages are often present in masochistic texts because adult experience reworks infantile desires, but these other fantasies are always undergirded by the primary oral fantasy for reunion with the mother as plentitude [71]; meanwhile, the superego’s attempt to spoil the masochistic fantasy accounts for the aggressive return of the father in Oedipal fantasies within masochistic texts. [72] This allows for the existence of the primal scene (e.g., the Narrator peeking at Tyler and Marla having sex), Oedipal triangles (e.g., the Narrator’s negative Oedipal complex toward Tyler, and positive Oedipal trajectory with Marla), and the rampant castration anxiety throughout Fight Club. Furthermore, because characters in fantasies are subject to dreamwork processes, the presence of fantasies from different developmental periods helps to facilitate the shifting of character identities [73]—which, I would argue, can be seen in Fight Club and other unreliable narratives involving multiple identities within a single protagonist.

If the first part of the film is transgressive in its opposition to consumerism, the second part of the film (after Project Mayhem begins and the Narrator learns that Tyler is part of his imagination) moves in a much more reactionary direction. Although virtually all critics psychoanalyzing Fight Club have correctly observed that Tyler represents the Narrator’s id, some consider the Narrator as ego and others as superego. In his position between adherence to society and loyalty to Tyler, I view the Narrator as ego—but Tyler’s role as id is complicated by something that critics have not remarked upon. As personified id, Tyler’s rebellion against a society/superego that no longer represents his masculine drives evolves into the threat of Tyler himself forming a primitive new society in which men would occupy their “natural” roles in a hunter-gatherer economy. But just as Tyler is repeatedly associated with the Narrator’s absent father, Tyler’s leadership of the subtly fascistic Project Mayhem (formerly Fight Club) makes him less representative of the Narrator’s id, and more a sort of rival superego with a new set of norms (albeit the same contradictory norms shared by the film, celebrating both phallic masculinity and bisexuality). Because Tyler is a large part of the Narrator’s psychic identity that becomes increasingly controlling as the film continues (quite against the Narrator’s will once this fact is discovered), the Narrator is torn between dueling superegos: that of a feminizing society already in existence and that of Tyler’s fascistic movement toward a naively utopian vision. It is not until Tyler assumes this rival superego function, with the advent of Project Mayhem, that the Narrator tries to uphold society’s superego order by stopping Tyler’s plans for “controlled demolition.” The “homework assignments” doled out to members of Fight Club by Tyler only amount to destructive pranks, but Project Mayhem poses a real threat to the structure of society; consequently, instead of embracing Tyler’s plan for chaos, the Narrator would rather save a society/superego that keeps him feeling disempowered and feminized (and thus in a masochistic role). Slavoj Žižek’s discussion of the film provides a possible motivation for the Narrator’s continued masochism: “When we are subjected to a power mechanism, the subjection is always and by definition sustained by some libidinal investment,” manifested in the performative act of masochistically “hitting back at oneself,” thus rebelling against the dominating society by making its domination seem superfluous now that the masochist assumes its power to cause pain and subjection (albeit by causing pain and domination to him/herself). However liberating this adoption of power may seem, true liberation can never be achieved because the pleasure in feeling disempowered always outweighs the potential for actual empowerment since “the only true awareness of our subjection is the awareness of the obscene excessive pleasure (surplus enjoyment) we get from it.” [74] Žižek’s comments would seem to support my argument (not just because they share the same work by Deleuze upon which Studlar based her theories), for the Narrator continues in a masochistic role, no matter which superego (society or Tyler) he is rebelling again, because the superego can never be fully expelled (except in death) from the mind of the masochist, who must defer satisfaction indefinitely.

It is because the film’s tone is so subversive in its first part that so much of its text-specific viewing pleasure is created; consumerism, traditional heterosexual relationships, and pervasive cultural ideologies are all attacked temporarily, but then the film moves into the more reactionary mode as the Narrator learns of his psychosis and attempts to stop Tyler (whose actions have likewise shifted from transgressive acts toward more authoritarian goals). As Bulent Diken and Carsten Bagge Lausten correctly note, “Rather than a political act, Fight Club thus seems to be a trancelike experience, a kind of pseudo-Bakhtinian carnivalesque activity in which the rhythm of everyday life is only temporarily suspended.” [75] The film becomes a sort of cautionary tale about the dangers of unleashing repressed anti-social desires, and because of the film’s carnivalesque approach, its view of gender and sexuality lose their transgressive qualities as well. “Only a psychotic break––[the Narrator’s] internal bifurcation––can free nonindividuated desires from the repression necessary to keep them dormant,” says Thompson. “This logic further demonizes homosexuality and social aims in favor of individuated, personal goals by situating the former in the domain of [the Narrator’s] psychosis.” [76] Thus, the Narrator’s move toward saving society corresponds with a move away from the homosexuality implicit earlier in the film, which, as I mentioned earlier, is regrettably necessary to avoid the contradiction between masculinity as lost plentitude and the powerful oral mother as lost plentitude (since psychic processes would place the masochist in the traditionally “feminine” role of the disempowered). “Even after the establishment of Fight Club,” which restores an awareness of traditional phallic masculinity, the Narrator “continues to disregard Marla as a sexual object,” Juhasz says [77]; however, I must add that it is only after discovering that Tyler is part of his own mind (a discovery resulting in fainting, a traditionally “feminine” symptom of hysteria) that the Narrator begins to build a traditional heterosexual relationship with her, first by taking responsibility for how he treated her as Tyler. This sort of guilty reappropriation of responsibility is the Narrator’s driving force during the latter part of the film, whether in his relationship with Marla or with society in general.

By the end of the film, the Narrator has fallen into the classical narrative formula of trying to save both the girl and society. Marla is brought by Tyler’s troops into the same building as the Narrator, as a means of “tying up loose ends.” In order to save Marla and society from his split personality, the Narrator shoots himself, symbolically killing the Tyler persona. Though it means legitimating society-as-superego, this is perhaps the supreme masochistic act since its proximity to death (the mystical solution to masochistic desire) would seem to expel Tyler-as-rival-superego and secure his reunion with both Marla (the _femme fatale_/oral mother figure) and a feminizing society (which always defers the plentitude of a lost masculinity), ensuring that his masochistic desire will never be fulfilled, except in actual death. Just as the Narrator’s comment that “everything’s going to be fine” is humorously undercut by the subsequent explosion of buildings, the ending of the film denies complete narrative closure. He and Marla join hands as they watch the buildings fall, implying the resolved Oedipal trajectory of a classical narrative, but their future together is highly dubious. The actual lasting effects of Project Mayhem’s “controlled demolition” are never explained, except as a step toward Tyler’s utopian goals, so it is unclear how that action will affect the Narrator’s life with Marla, just as his acceptance of responsibility could easily entail another surrender to authorities––but this is all conjecture, an attempt to construct future fabula events without the cues to do so. With the Narrator/Marla union, the apparent exorcism of the Tyler persona, and the completion of Project Mayhem’s specific goal, Fight Club ends on a note of semi-closure characteristic of major-studio unreliable narratives. In this sense, the conclusion also resembles in many ways a conventional noir ending: a death or loss (especially of the “buddy” character), a sense that the femme fatale has been domesticated into a traditional familial role, an exorcism of the past, and an unresolved anxiety within the protagonist’s mind about how the resolution has been reached. [78] A specific element of ??Fight Club??’s visual style––metacinematic references to the medium of film itself (e.g., visible spindles, “cigarette burns,” etc.)—interrupts the convenient Narrator/Marla union, casting the film’s move toward classical closure into doubt. This element is in the form of a “nice big cock”––the image of a phallus representing Tyler––spliced into the film’s final frames, just as Tyler had spliced it into the classical narratives of family films. As Thompson notes, this image implies that Tyler (and the anti-social, homoerotic desires he champions) can never be completely banished back into the Narrator’s id [79]—though I would argue that it also implies how the superego (i.e., a rival superego with contradictory norms, in this case) can never be completely expelled in the masochistic scenario.

I have already posited that unreliable narratives like Fight Club produce a masochistic pleasure on both a spectatorial and diegetic level, but what does that mean for spectators of various genders? It is my contention that spectators of either gender may experience a masochistic spectatorial pleasure created by the formal narrative strategies of these films (since spectatorial pleasure does not rely on identification with a character), but male spectators may have a more vested interest in the masochistic narratives being played out on the diegetic level. Because unreliable narratives tend to focus on male protagonists with threatened masculinities and unstable identities, male spectators may identify more strongly with these specific protagonists than female spectators. As Studlar says of masochistic texts, “If the male spectator identifies with the masochistic male character, he aligns himself with a position usually assigned to the female.” If this position is not acceptable to the spectator, identifying with either the strong female or an androgynous male character become the only alternatives––in any case, identifying with something associated with the feminine. [80] This is not to say that female spectators cannot identify as strongly with the male protagonists, especially if those protagonists occupy a traditionally feminine position, but my argument rests upon the link between a shared crisis of masculinity felt by male spectators in contemporary society and by the male protagonists reflecting that crisis on the movie screen. The masochistic spectatorial pleasures afforded to female spectators by the form of unreliable narratives may in effect help to sugar the bitter taste that might otherwise result from the male-centered concerns operating within the diegesis itself. Studlar notes that if cinematic fantasies come closer to the spectator’s own fantasies (or, in my argument, the male spectator’s own life), then the enjoyment of the masochistic fantasy is all the more perversely (un)pleasurable. [81] Since a large part of masochism’s appeal relies on its temporary dissolution of ego boundaries (which allows shifting identifications that transgress patriarchal norms), I believe that unreliable narratives especially serve to accomplish that wish for dramatically similar fantasies. Studlar writes that, because the end of any film restores ego boundaries, the spectator’s ego cannot be threatened by the apparatus to the extent that psychosis results and he/she begins living the cinematic fantasy after the film concludes. [82] However, Studlar later admits that a failure to fully separate from the dream screen at film’s end can result in a clouding of one’s waking vision. [83] Therefore I would like to contend that unreliable narratives come closer to creating a psychosis, a clouding of one’s vision, than any other type of film, due to their especially marked use of unstable identities and unclosed narratives. Since the masochistic experiences of the films’ protagonists tend to overlap so significantly with the experiences of contemporary male spectators in regard to a threatened sense of masculinity, the possibility for these films to influence the waking vision of their male spectators is made even greater. [84]

The paranoid aspect of narratives functioning under the logic of a crisis of masculinity is explained by Fradley:

If we posit that power and paranoia are little more than noirish mirrorings of each other, delusions of persecution thus structure the identity of the male subject: paranoid counter-narratives make connections and (re-)order their universe, anxiously re-cohering the world, quite literally, around it self. As such, the grandiose narcissism of the paranoiac can be seen as a form of (over-) compensation for displaced feelings of (personal, cultural, and/or socio-economic) worthlessness and inadequacy. Paranoia thus works in a cyclical double-bind, staging various masochistic fantasies in order to master them. [85]

This paranoia is also attributed in part to “the abjection of the postmodern condition” [86]––fears about losing control in a postmodern world that denies any sort of stable identity formation, but especially frightening for males accustomed to their place of privilege in a patriarchal society. If we apply this logic to unreliable narratives, paranoia then operates in order to focus the narrative toward a desired recuperation of masculine identity. Through the loss of identity/ego boundaries as created by the apparatus and intensified by unreliable narrative strategies, and through identification with the suffering male protagonist, the male spectator temporarily experiences a pleasurably transgressive loss of power. “The sadomasochistic allure of male powerlessness is not subversive of the paternal law of the masculine symbolic,” Fradley continues, “but a mythic, ritualized, and recuperative strategy based on the double-bind of disavowal: the hero knows he will get his ball(s) back, but chooses to believe, albeit briefly, that the lost object is irretrievable. […] Thus, the narrative drive toward remasculinization is structured on a prior feminization.” [87] However, I must specify that unreliable narratives do not provide that remasculinization within the constructs of classical narrative closure like other contemporary depictions of masculinity. Instead, unreliable narratives require that the male spectator take a more active role in the recuperation of his identity. The pleasures of ego fragmentation depend upon the resolidification of a newer, more coherent ego identity, says Studlar [88], and this is achieved in unreliable narratives by the spectator’s active reconstruction of the fragmented fabula after the film’s end. Though this act of reconstruction may be a pleasurable activity for spectators of either gender, for the male spectator it is especially crucial; as a reaction against the crisis of masculinity reflected in the film, he must piece together a sense of ego stable enough to allow proper exercise of his hegemonic duties in a society that is still a patriarchal system, despite the best efforts of the liberation era. It is precisely because white, heterosexual, middle-class men––a demographic, I should point out, comprising both the combatants in Fight Club and a large share of the audience of unreliable narratives––are already so secure in their real hegemonic power that they can find pleasure in fantasies that so radically (and temporarily) destabilize that power, says Fradley. [89] Fabula reconstruction notwithstanding, the lack of resolution inherent in these films serves to perpetuate male anxieties indefinitely, ensuring the continuance of a narrational mode that reflects an ongoing reactionary masculinist zeitgeist destined to pop up again and again from a collective male cultural subconscious with all the thrust of a spliced-in phallus.

I must acknowledge the gracious help of Douglas Park, Martin Fradley, Gaylyn Studlar, and Steven Shaviro in the research and writing of this essay. An earlier version of this essay was presented at the 2005 National Undergraduate Literature Conference at Weber State University.

Endnotes

1 An examination of the cult activities associated with the film is outside the scope of this essay, although the numerous “copycat” Fight Club’s that it inspired, that is actual “underground boxing rings” begun in emulation of the movie, is a phenomenon worth further study.

2 By calling certain films “mainstream,” “Hollywood,” or “major-studio,” I only mean in terms of having wide distribution by the largest Hollywood studios.

3 David Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), p.54.

4 Ibid., p. 39.

5 Ibid., p. 54.

6 These antecedents include The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Robert Wiene, Germany, 1919), Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, US, 1958), Last Year at Marienbad (Alain Renais, France, 1961), La Jeteé (Chris Marker, France, 1963), Belle du Jour (Luis Buñuel, France, 1967), Solaris (Andrei Tarkovsky, Russia, 1972), and Videodrome (David Cronenberg, Canada, 1982).

7 Genre examples include horror (The Sixth Sense [M. Night Shyamalan, US, 1999], The Others [Alejandro Amenábar, US, 2001]); science fiction (The Thirteenth Floor [Josef Rusnak, US, 1999], eXistenZ [David Cronenberg, Canada, 1999], 12 Monkeys [Terry Gilliam, US, 1995]); comedy (Being John Malkovich [Spike Jonze, US, 1999], Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind [Michel Gondry, US, 2004]); action (Fight Club); and all manner of dramas (Mulholland Drive [David Lynch, US, 2001], Spider [David Cronenberg, Canada, 2002], Memento [Christopher Nolan, US, 2001], A Beautiful Mind [Ron Howard, US, 2001]).

8 Examples include Abre Los Ojos (Alejandro Amenábar, Spain, 1998), Suzhou River (Lou Ye, China, 2000), and various earlier films named in note 6. It is interesting to note that several non-American directors (e.g., Hitchcock, Amenábar, Gondry, Nolan) have directed unreliable narrative films especially for the US market (see notes 6 & 7).

9 Bordwell, p. 150.

10 Ibid., p. 162.

11 Ibid., p. 209.

12 Ibid., p. 159.

13 Edward R. Branigan, Narrative Comprehension and Film (London and New York: Routledge, 1992), p. 95.

14 Ibid., p. 105

15 Here a distinction should be made between unreliable narratives and other films with complex syuzhet structures. Many films (especially since the 1990’s) may creatively use the syuzhet in order to generate non-linear stories, but true unreliable narration depends upon a very high degree of subjectivity in order to deceive the spectator. Compare, for example, the unreliable, highly subjective narrative of Memento to the more reliable, highly objective narrative of Irreversible (Gaspar Noé, France, 2002); both films use non-linear structure to tell a story in reverse order, but only Memento frames its story entirely through memory as a subjective device.

16 Bordwell, p. 165.

17 Compare, for example, spectator reactions between Lynch’s Lost Highway and its more accessible counterpart, Mulholland Drive; or the notoriously confusing Last Year at Marienbad, which Bordwell points out as effectively lacking a fabula to interpret since “ambiguity [created by the syuzhet] becomes so pervasive as to be of no consequence” (p. 232-3).

18 Jean-Louis Baudry, “The Apparatus: Metapsychological Approaches to the Impression of Reality in Cinema,” in Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (Eds), Film Theory and Criticism (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 770-772.

19 Gaylyn Studlar, In the Realm of Pleasure: Von Sternberg, Dietrich, and the Masochistic Aesthetic (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988), p. 180.

20 Ibid., p. 31.

21 Ibid., p. 184.

22 Ibid., p. 16-17.

23 Ibid., p. 52.

24 Ibid., p. 26, 43.

25 Ibid., p. 97.

26 Ibid., p. 28.

27 Ibid., p. 185.

28 Ibid., p. 185.

29 Ibid., p. 181.

30 Ibid., p. 183.

31 Ibid., p. 132.

32 Ibid., p. 15.

33 Ibid., p. 97.

34 Bordwell, p. 39

35 Studlar, p. 112, 116.

36 Ibid., p. 181.

37 Ibid., p. 126.

38 Ibid., p. 184.

39 Steven Shaviro, The Cinematic Body (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), p. 43-44.

40 Studlar, p. 111-112.

41 Ibid., p. 93.

42 Ibid., p. 144.

43 Ibid., p. 158.

44 Ibid., p. 170.

45 Ibid., p. 124.

46 Ibid., p. 216, n. 23.

47 Ibid., p. 126-27.

48 Ibid., p. 191.

49 Ibid., p. 188.

50 Ibid., p. 24.

51 Ibid., p. 52.

52 Even in a film with a female protagonist, such as Mulholland Drive, these structural elements are present; for example, if Diane (Naomi Watts) were replaced by a male character and Camilla (Laura Elena Harring) remained the femme fatale, the basic plot would bear many similarities to Lost Highway.

53 Bordwell, p. 154.

54 Martin Fradley, “Maximus Melodramaticus: Masculinity, Masochism and White Male Paranoia in Contemporary Hollywood Cinema,” in Yvonne Tasker (Ed), The Action and Adventure Cinema (London and New York: Routledge, 2004), p. 236, 238.

55 Sally Robinson, Marked Men: White Masculinity in Crisis (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), p. 12-13.

56 Ibid., p. 12-13.

57 Fradley, p. 239.

58 Fradley, personal communication.

59 I am not trying to argue that concern over masculinity in crisis is the only underlying process of these films as a mode, but it is the one process that I am focusing on within the scope of this essay.

60 Douglas Pye, “Film Noir and Suppressive Narrative: Beyond a Reasonable Doubt,” in Ian Cameron (Ed), The Book of Film Noir (New York: Continuum, 1992), p. 99.

61 Fradley, p. 238.

62 Ibid., p. 236.

63 Robinson, p. 11.

64 Alexandra Juhasz, “The Phallus UnFetishized: The End of Masculinity As We Know It in Late-1990s ‘Feminist’ Cinema,” in Jon Lewis (Ed), The End of Cinema As We Know It: American Film in the Nineties (New York and London: New York University Press, 2001), p. 215.

65 Stacy Thompson, “Punk Cinema,” Cinema Journal, Vol. 43, No. 2, Winter 2004, p. 58-59.

66 Henry A. Giroux and Imre Szeman, “Ikea Boy Fights Back: Fight Club, Consumerism, and the Political Limits of Nineties Cinema,” in Jon Lewis (Ed), The End of Cinema As We Know It: American Film in the Nineties (New York and London: New York University Press, 2001), p. 101-102.

67 Thompson, p. 59.

68 This is emphasized in a dialogue between Marla and the Narrator midway through the film (before either of them realize his split personality):

Narrator: Why does a weaker person need to latch onto a stronger person? What is that? [implying that Marla is latching onto “Tyler”]

Marla: What do you get out of it? [implying that the Narrator is weaker and latching onto her, the femme fatale]

Narrator: No…it’s not the same thing at all. I mean, it’s totally different with us. [“us” meaning him and Tyler, as he misinterprets that she is accusing him of latching onto Tyler, despite her being unaware of the Narrator’s two distinct personas]

Marla: Us? What do you mean by “us”? [unaware of the relationship between the Narrator’s split personalities, since he primarily interacts with her as the “Tyler” persona]

69 Studlar, p. 58.

70 Ibid., p. 16.

71 Ibid., p. 57.

72 Ibid., p. 25.

73 Ibid., p. 53.

74 Slavoj Žižek, “The Ambiguity of the Masochist Social Link,” in Molly Anne Rothenberg, Dennis Foster, and Slavoj Žižek (Eds), Perversion and the Social Relation (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003), p. 118-119. Italics in original.

75 Cited in Žižek, p. 121.

76 Thompson, p. 60.

77 Juhasz, p. 212.

78 Deborah Thomas, “How Hollywood Deals With the Deviant Male,” in Ian Cameron (Ed), The Book of Film Noir (New York: Continuum, 1992), p. 68.

79 Thompson, p. 60.

80 Studlar, p. 44-45.

81 Ibid., p. 183.

82 Ibid., p. 181.

83 Ibid., p. 187.

84 Whether or not this was an unconscious factor inspiring the various “copycat” Fight Club’s begun by male fans of the film can only be speculated upon.

85 Fradley, p. 238.

86 Ibid., p. 239.

87 Ibid., p. 239-40.

88 Studlar, p. 190.

89 Fradley, p. 250.