The City Without Windows

Melancholic SF

La Dernière Voix (The City without Windows) is a short science-fiction film [12’43”] written and directed by Montreal-based filmmakers Karim Hussain and Julien Fonfrède. The film is set in a post-apocalyptic future where there is no escape from a constantly falling acidic rain. The rain has brought along a fatal virus which first attacks the vocal chords and then leads to death. As a result technology as we have come to know it is a thing of the past, and with it all forms of human communication. The only “medium” of communication in this dying world is the human body, with people using a scalpel or razor to carve words onto human skin. Within this vast global apocalypse is a tale of love lost between a black man (Marc-Andy Henry) and a black woman (Mahalia Verna), with a white woman (Lexei Bacci) used as the man’s medium of communication. The film, shot on 35mm without sync sound, contains a voice-over narration and sound and music composed by longtime Karim Hussain collaborator David Kristian.

The City without Windows was financed by the Québec provincial funding bodies SODEC (Société de développement des entreprises culturelles) and Télé-Québec and was subsequently nominated for a Claude Jutra Award in the best short category of 2003. Although the film was released in 2002 this interview nicely coincides with its DVD release on a German produced special edition DVD of Karim Hussain’s first feature film Subconscious Cruelty (which has already been treated in an in-depth interview on Offscreen), which also includes the award winning short film by Mitch Davis Divided Into Zero (who also produced Subconscious Cruelty), a documentary and a making of.

In the same year as The City without Windows, 2002, Karim made his second feature film, Ascension, on which Julien Fonfrède worked as Associate Producer and First Assistant Director. The film, a darkly comic, prophetic and philosophical science-fiction film, has unfortunately not fared as well as The City without Windows in terms of exposure. After winning the New Vision Award in the 2003 Official Selection at the prestigious Sitges Film Festival, the film has languished in limbo due to political complications with the Japanese investors. It has yet to be released anywhere in North America. The film is due for DVD release in Japan in August. However, things look bright for the near future for both Hussain and Fonfrède, who are scheduled to begin shooting their second feature film, entitled La belle bête, in August 2005 (also funded by a production grant from SODEC). La belle bête is being produced by Hussain, Fonfrède, Anne Cusson, co-produced with Equinox Productions. The film, described by Hussain as a “dark love triangle,” is based on the well known Québécois novel by Marie Claire Blais, La Belle Bête (Mad Shadows), published in 1959. As if all this were not enough, Hussain will also see a script which he co-wrote with Nacho Cerdá slated for production at the end of the summer. The film is entitled Bloodline and will be directed by Cerdá (who was interviewed on Offscreen years ago about his gut wrenching short film Aftermath, 1994).

This interview was conducted in Montreal on October 17, 2002 during the Festival of New Film and New Media, where the film showed.

Offscreen: There are many ways one can read La Dernière Voix (The City Without Windows). It is an intricate film designed as an open text. In one sense it is metaphorical. In another sense it is strictly science-fiction. Even the voice-over, which is an important component of the film, relates in that it gives you exposition in terms of what happened and has a poetic side as well. Can you talk a little bit about how you see those two styles the science-fiction and the poetic or metaphorical working together?

Julien Fonfrède: The fantasy aspect definitely comes naturally as soon as you invent another world. We really didn’t want to do a science-fiction movie. We wanted to create another world that has its own rules, which is what gives it the fantasy element, but at the same time it is like a drama, a poetic love story, or a cynical relationship story. These things came quite naturally without much thought.

Karim Hussain: The movie is a dual narrative where at a certain level you have an intimate love story or the end of a love story which is the consequences of this status quo of what everything has become. Whereas at the same time, because it is a “science-fiction” universe, we had to reinvent the rules for the audience. So it was very important to keep things relatively ambiguous up until the end and not give all the answers from the beginning. We wanted you thinking, why is this man here? why is he going through all these ritualistic things? why is he cutting into this woman? and at the same time we have a more global view of this apocalypse. So there would always be the question of what is going on to motivate the audience to go from one scene to another, which accounts for the unfolding dual narrative. There are a lot of ambiguous elements in the film, like the question of race, communication, and of how far people are willing to go to retain an illusion of humanity, an illusion of civilization. Even though, left on their own they will go into complete and total insanity and distortion of a basic hysterical reaction, which is certainly something we are seeing in the world today, people hysterically overreacting and then suddenly seeing everything in “black and white” terms. This is one of the metaphorical things about the film in terms of race, that when people are pushed to that extreme of fear and hysteria and become less able to maintain control they will push into very bizarre and somewhat obscene and insane rituals to remotely retain any illusion of humanity. So it is really a film about, amongst other things, struggling: the struggle to relate to emotions and to retain some sense of order, some sense of religion and personal self-worth. Even if that self-worth means people are going to cut into your body and you are going to be walking around like human paper, well at least that means something, that you are not just a dying creature. You have a purpose.

Julien Fonfrède: Yes the desperate need to have a purpose is also a part of the dual aspect. There are two levels to the story, the narration and the actual actions which happen in the film, which work on a different level, a bigger than life level of a universe where you explain what is going on a little by little. And under that you have a very simple story that has no existence outside of these 13 or so minutes. That is also how we worked the fantasy and the metaphor into the actual storytelling to make it more dynamic.

Offscreen: One of the ways that I read the film is that, while it is obviously about memory, it is also about how history is written and recorded. How we keep sense of ourselves and our past, with the truism that “history is written by the winners,” as Winston Churchill said. If that is the case, the question is, who was the winner in this scenario? To add a second question: is it a coincidence that the central character is black? Or is it like Night of Living Dead (1968), were it was simply a coincidence.

KH: No it was not a coincidence.

Offscreen: Let me just follow up. If the black character is the one doing the writing, if he is the winner in this scenario, the irony is that, in a sense, the white people are still in a superior position because they have the necessary pigmentation to be written on because the blood would not show as well on dark skin. Is that an intended irony?

KH: Yes it is and there is plenty of irony in the film. Basically no one will win when they are pushed into such an extreme direction.

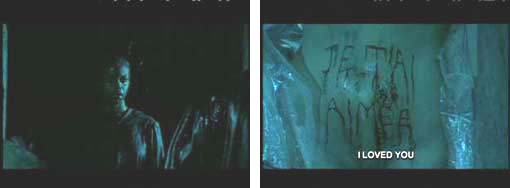

JF: The woman is actually the one who has a kind of strength and purpose and is the important person within the text. She has the pride of carrying the man’s message, that the two lovers, the black man and the black woman, lost something. Yes the man can tell her ex-lover “I loved you,” but it is just accepting the fact that something is gone, something is dead already. The white woman has the pride of carrying the message of love. So there is a lot of irony in those two characters.

Offscreen: She is also very pale, with white hair.

JF: The racial politics as it is written is more a consequence of the practical aspects in that white flesh would be better to write on and not that it is something very political.

KH: That they are willing to see communication on human flesh as practical is a completely insane and terrifying idea. That is one of the ironies of how people will push themselves to extremes. If you were going to take that saying today, “that history is written by winners,” then obviously no one has won here and history is going to be written in something that is going to die and rot anyway. It is really a film about this quite frightening “black and white-ism” which creates a scenario where people are going to push and invent or reinvent their own frightening and dangerous religion at the end of the world. Of course everyone is going to die anyway, so what can be dangerous when there is death in a very short period of time? These are some of the questions we wanted to raise with this movie and leave it relatively ambiguous. We wanted to leave it so there would be things people could talk about.

Offscreen: In terms of the religious aspect, when we see the black man showering from behind the framing with the bar behind him forms a cross which makes him look like a Christ figure.

KH: You are the first one to have said that and it certainly was not our intent when we shot it, but that is cool that you saw that.

JF: It must be a sign!

KH: Maybe, but it was completely not intended.

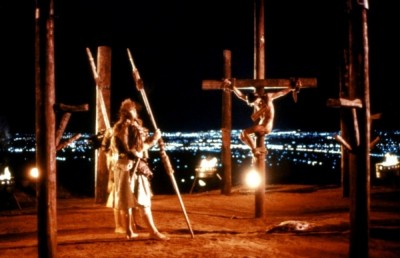

Offscreen: Is he the same character that we see in between the man (actor Chris Piggins) and the woman near the end?

KH: No that is a priest (actor Adrien Lacroix).

Offscreen: To me that image seemed like Adam and Eve in a new beginning and that maybe there is a bit of hope in the sense of a new genesis, because in the voice over there is mention of a new future.

KH: Yes, and the new future is of course the end of the world for them. No it is not meant to be an image of hope. It is just a case of another marriage taking place which gives a bit of a back story of how these white and black people are matched up and how they don’t make the decision of who will be their “paper” and “communicator.” That is done by an above power, some form of hierarchy, like a “priest.”

JF: It was a very practical thing for us to show that it is not just women who are written on.

Offscreen: All the constant rain of course also recalls the Biblical passage of raining for 40 days and 40 nights in the Old Testament, with the coming of the apocalypse and then something new being reborn.

KH: Sure.

JF: I don’t think we went that far. It was more accepting the fact that things were ending in many ways, whether it was love or the world. The film is about the acceptance of the end. With the contradiction that the writing on the body is something that stays.

Offscreen: I imagine that the film looks the way it does because of the sadness and sense of elegy in the story, theme and characters?

KH: Yes of course, with the images as well as the music, which is a very very important component to the film. When we got together with David Kristian that was one of the principal vibes, because we always work on the music before we start shooting a movie. The script came first and then the music. It was done about a week or two before the shoot and that way we had to perfectly express the sense of melancholy and sadness. We would often play the music on the set as well so people would understand. It is interesting that you mention this raining for 40 days and 40 nights because these are things that may have been in our unconscious, so even though we were not aware of it you never know where your ideas are coming from.

JF: The aspect of the constant rain actually came first. Our first thought for the story was, what would happen if it rained all the time and windows disappeared, making the distinction between inside and outside disappear. From that we added the aspect of the virus being spread with the water. So the rain came first as an image and after that came the story.

Offscreen: In the beginning of the film there is the shot of the man inside his house looking out and it looks like the water is coming straight down in a sheet.

KH: No, that is concrete. It is a reflection of light that makes it look like a wall of water. It is a very beautiful effect that was all done through reflections and the angle of where the lights were placed. It was intended to look that way which is why in many ways the film is a visual poem. It is a fairy tale or an adult fable about the end of the world because we are now faced with a similar impending apocalypse. It is a reflection on that certainly. We conceived the movie before 9/11 and the idea of the apocalypse wasn’t as present as it is now, but movies find their audiences and find their time, and time finds their movies to be made within. It just ended up being exceptionally ironic that this very apocalyptic movie ended up being made and shot during a very apocalyptic time. To the point where the Vancouver Film Festival that programmed the movie put it into the documentary section, which was a very strange thing; and it was considered to be a non-Canadian film! It was considered to be a foreign documentary!

Offscreen: The audience must have been quite shocked?

KH: Confused. It makes you think, “do the people in Vancouver know something we don’t know!”

JF: About Québec!

KH: Exactly! It is just ironic that it was programmed as a documentary because it is such a fictional fantasy movie… or is it?

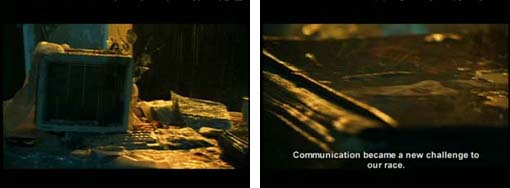

Offscreen: To get back to David Kristian, who wrote and composed the music. One thing I liked a lot about this soundscape is the constant sound of what seemed to be the scratching of an LP record on a turntable, because it creates an effect of constant revolution. This is or sounds like old analog technology. Is the film at all anti-technology or implying that technology was part of what led to the problem?

KH: What is really ironic about a movie that sounds very analog and old school is that absolutely everything in the soundtrack, including the sound of the record player, was done digitally and was done off a computer. So it is not that technology is evil or bad, but that the rain has effectively destroyed technology. So that amongst love being lost, and technology being lost, there is a sense of melancholy and nostalgia permeating every frame of the movie. We wanted to make a movie where there is nothing but rain in the movie, without ever hearing the sound of rain. That was a very specific request we had made to David and David came up with the great idea of the sound of the record player. David makes everything good.

JF: The idea was to not use the sound of any actual rain, but that the sound of the scratch on the record being looped gave the sensation of something dripping. I think it is a very subliminal thing and if you see the film on a big screen you get a very organic reaction to it which is very interesting. There is something on that subliminal level with those sounds.

Offscreen: The sound and rain imagery makes me think of a film I know you, Karim, like a lot, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), not that we have to go into that too much.

KH: No we don’t, but hey Tarkovsky is the best. We did not think of Tarkovsky or any specific filmmaker or movies when we made this movie. It was just a question of meeting the demands of what the movie needed. Obviously those kinds of feelings and visual motifs that Tarkovsky was into are also ones that moved us as well. He is not the only one that uses them, even though we use them in very different ways.

JF: The only thing we used as a reference in talking to each other or to other people to understand what we wanted was The Element of Crime (1984) by Lars von Trier, with the rain and the lighting, but beyond that there is no direct inspiration. A lot of people say it reminds them of The Hole (1998) by Tsai Ming-liang, or La Jetée (Chris Marker, 1963) Memento (Christopher Nolan, 2000), Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982), Tarkovsky ofcourse…

KH: Baudelaire, J.G. Ballard, which was the one I like the most because I really love Ballard.

Offscreen: Not exactly bad company to be in. Once a film gets made it becomes part of this vast image archive and people access it however they can depending on where they’re coming from.

KH: But it is good too of course. I would rather those comparisons than to Ghost Ship (Steve Beck, 2002) or something like that.

Offscreen: Actually there was 1943 film by that title produced by Val Lewton and directed by Mark Robson which is very good but you’re not referring to that one of course. There is a line in the film that is quite telling. It is when they are talking about writing on the body and because you can not erase it: “We became honest again.” I would like to know, when were we ever honest!

JF: I could explain that but….it seemed very poetic. There probably was a time –way back– when we must have been honest.

KH: I don’t think we were ever purely honest, but now lies are being spread through hysteria in mass media from governments to such extreme proportions and to levels that were never done before. Propaganda has been taken to a level that was never possible before, when there was still a certain lack of power in being able to spread a message without any sense of proof or justification. But now a government can say anything and not really back it up. So it is not that we are more or less honest than before but we have more of a wide spread capability to lie now. Certainly after this technology has disappeared you can no longer cover yourself up with fancy words or visual lies and very trickily worded press releases. If the message is cut into the flesh it has to be honest again.

Offscreen: Well part of what the film may be saying is that modernity and technology has given us the tools to become dishonest, like a lie detector machine which is supposed to the detect whether a person is lying or not.

JF: It could work on many levels in terms of honesty. For example, through nudity the honesty was rediscovered.

KH: I would be surprised if people all thought the same way about the film. I just put in a possible theory about that phrase but we wanted to have something that was pretty open ended and that could be interpreted in many different ways. Look at the Pope’s recent visit to Toronto. He was saying the most banal and simple things that were completely misappropriated by everybody into these hidden subliminal messages, as if the Pope were speaking some form of binary code which was only decipherable by good Catholics. These mysterious “1’s” and “0’s” were popping out of these moaning phrases and, if you are a good Catholic who believes, “Eureka,” it will be suddenly like deciphering a 400 page discourse from a simple sentence. Something like, “you must go with Jesus” suddenly became a discourse on abstinence from sex. That kind of hysteria is not present in the movie but you can appropriate it on many levels. But again these things are up to the audience.

JF: Remember if you want to get to a utopian state you have to have the faith that it once existed.

Offscreen: Just from a very pragmatic point, the more intermediation you have between the communicator and the communicatee, the more room there is for misinterpretation. Just look at how easily an e-mail can be misinterpreted. So when you are going back to communicating literally on the body it is a final and very direct process.

KH: Even a simple speech! Speech is getting pretty tough and people are acting hysterically over things which they might not completely understand. You can make a mistake in what you say and not have time to correct yourself before people go on a rampage. Communication is now more fallible than ever to even unintentional lies and mistakes just because we are so bombarded with information that misappropriation is more present. Which makes this a very fragile reality. Again one of the small metaphors in the movie can be applied to our every day lives, which is one of the things we wanted to do with this, a film which is very modern and very actual while being in a world that does not exist….yet.

Offscreen: A Canadian cultural critic called Harold A. Innis wrote a book called The Bias of Communication in 1951 which is still one of best studies on communication. He went back to the 10th century and studied how people communicated and the evolution of that communication. Basically, his main point was that each system of communication had its own ‘bias’ based on how quickly or slowly the communication was transmitted, and that as the means of communication changed so did society. With the oldest forms of communication people used to write on very heavy mediums like parchment, clay and stone. He called that a technology with a temporal bias because it took a long time for the message to get a cross and there was a certain truth there and less room for error. Then when technology became lighter and faster, when it moved to papyrus, paper, print, and electronics it became ‘faster’ and moved toward a spatial bias. Like now of course with digital communication it is instantaneous, and as this happens it changes what we think about, what we think with, and how we think. When I saw your film it made me think of Innis and I thought it was going back to the beginnings of communication, literally starting from scratch, using the human body as a Tabla Rosa and learning how to re-communicate.

KH: Well that is the idea but at the same time they are learning to re-communicate when everyone knows they are going to die. It becomes more of a reassurance than anything else.

JF: Or a desperate act.

Offscreen: The voice-over never does say that they are going to die, only that they are going to get sick and lose their voice.

KH: Well when it says “everything will be drowned by eternal rain,” we mean literally, drowned. However it can be appropriated in other ways, especially with the last communicator. But when she is talking she does not talk about new beginnings. Unfortunately I wish we were that optimistic and nice but we are actually horrible and mean boys! In the English translation drowned means dead. So unfortunately the rain will take over to a point where you will not be able to escape it.

Offscreen: How was the constant rain achieved from a technical standpoint?

KH: We used rained towers and all of the water came from fire hydrants. Unfortunately it was exceptionally cold water. The whole film was shot in the dead of night during a very cold September. A few days after September 11th actually. The shooting of the film was a surrealistic thing in that it did seem as if we were making the movie at the end of the world. The film was shot in two and a half days, to accommodate a very small budget.

Offscreen: How large was the crew?

JF: About 10 or 15 including craft.

KH: We had a very good crew. We used a lot of the same crew on Ascension, the new feature film that we are finishing now. It was quite difficult on the lead actress Lexei Bacci, who is also a very well known porno actress in Montreal. She was naked and getting very cold under the freezing cold rain, to the point where she began hallucinating and could not finish some shots. The shoot did take a toll on her. I think any one less strong than her would not have being able to do it.

JF: It was very very difficult for the actors that is for sure. We thought it would be very difficult for us also but because the company we used for the rain effects, Les Productions de L’intrigue, were so good it was no problem. We were afraid about wetting the equipment, about getting electrocuted but everything was very well planned.

Offscreen: Was this story boarded?

KH: No. We had a shot list in advance because I was also the cinematographer, but this was a co-direction in every single aspect. Julien and I were pretty much on the same page with the movie. The content of each shot and the placement of objects in the frame was all pre-planned on paper between us so that we would go on the set and just carry on with what we needed to do.

Offscreen: Julien, I know you have worked on some documentaries but this is your first fiction film.

JF: Yes I did a few TV documentaries, and I worked as a production manager on a documentary on Hong Kong cinema.

Offscreen: How was the experience of co-directing your first fiction film?

JF: The co-direction makes things easier because Karim is an ultra professional and knows exactly what he is doing and knows how to improvise. It is a little bit like being on the set with Clint Eastwood on Heartbreak Ridge where they teach you to adapt, improvise, and dominate. I was Mario Van Peebles and he was Clint Eastwood. I cannot say it was tough because the funding of the film went very well. We had little money but we had enough to do the film so there were no horror stories on making the film. Maybe if I direct the next one alone I will have more horror stories to tell you.

KH: That is really our philosophy when we shoot something: to be very well prepared and to know how much film you can use for “X” shot. So as not to do too many takes, you rehearse a lot and make sure that everything is well planned in advance, which is something that a lot of directors can not do. I’m not saying that as a good or bad thing but a lot of directors need to find the movie as they make it, whereas we have to know the movie before we make it. Mainly because our budgets tend to be very low and we have very few days to shoot our movie. In Québec if your film is not about beer swilling guys playing hockey you can not get a lot of money or time to make your movie. Basically no one has done movies like this before in Québec. Thankfully there is a new generation of young people who are trying to make original films, not just horror/slasher movies, but trying to do fantasy and poetic films.

Offscreen: I wanted to get back to the film and discuss some specific shots. There is one I like quite a bit when the black character is standing in front of a mirror and he has to wipe the rain from the mirror.

KH: That’s a joke of course!

Offscreen: The camera dollies in slowly and there is a jitter effect in the movement…. was that just the mirror moving?

KH: Yes

Offscreen: It was really a nice effect.

JF: It was not planned but when we saw it we left it in.

Offscreen: At the end of Michael’s Snow’s film Back and Forth (1969) we have a camera panning back and forth slowly and quickly but every time it reaches the end of its arc you hear the sound of it hitting against the tripod. It is a real physical connection between the camera and tripod. And there too you have that very real, physical connection between the camera movement, the mirror, and the character’s hand.

KH: Well that is the kind of fun little thing you discover when you shoot a movie. The image of the guy looking into the mirror was supposed to be a joke on how in so many art house movies there is the shot of the person looking at their eyes in the mirror. Every student film seems to have that. Most of our stuff has a strong undercurrent of humor that a lot of people do not really get. Like in our first movie Subconscious Cruelty when the hippies are fucking the ground; it is kind of funny and is supposed to be funny.

Offscreen: Which shot took you the most time to choreograph and execute?

KH: The one at the end with Lexei Bacci standing at the door with the water coming down was very difficult. This with the last thing we had to shoot with the actress who was getting very cold and nearly paralyzed.

Offscreen: Does that explain why she seemed very stiff?

JF: Yes.

KH: Certainly when they built the forest with the priest in the tunnel that was difficult and complicated, but definitely the ending when they had that scene at the doorway was one of the most difficult. That was the first thing we shot on the last day. Bacci was at her wit’s end. Because of the pouring water her makeup began to peel and on a big screen you can see that under the make-up her lips are pitch blue. She was going into hypothermia. At that point we played the good cop, bad cop thing were Julien becomes the good cop, the one who they can all go to to bitch about me, and I become bad cop, the guy behind the camera with the big lens. It was a similar thing on our first feature together Ascension because Julien was first AD on that and I was the cinematographer and sole director. I was the evil guy who asked them to do stuff and Julien was the nice Frenchmen, with the nice soft eyes.

JF: We expected some of the problems on that film but in the end it was a very easy shoot because of the crew and the preparations. We actually finished about an hour-and-a-half early on both days, which made everyone happy of course.

Offscreen: The actress Lexei Bacci has a very odd physical look; her body type is strange.

JF: When we saw her we were very happy because she was exactly what we were looking for, someone who had a body that does not say “submission.” She has a very strong body language so there was a strength there with her character, which we were very happy with. If we had a very sexy body it would not have been the same.

Offscreen: She actually looks to me like Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) at the end of Blade Runner.

KH: Yes, almost. One of the interesting things about her is that she has no eyebrows and her face is almost a blank canvas, other than her piercing eyes. She gives the impression of someone who, before this revelation took place, had been very body conscious and very much into body modification, with her breasts and things like that. To take someone with such a theatrical and startling body can maybe shock some people. At the same time some people will see the body as a work of art. The fact that she had obviously done things to her body goes into the subliminal psychosis of the character, and the subliminal makeup of the character: someone who is willing to submit her body to an ideal and willing to go through a physical process of pain in order to achieve a goal.

Offscreen: Sorry to interrupt but you said that the priest character is the one who selects the person whose body will be used as a writing tablet. How does he make the selection?

KH: It is in your imagination

JF: The priest is a matchmaker… maybe white people who he did not like before…

Offscreen: Given the black and white duality and the “body politics,” where do mulatto people fit in?

KH: They are in trouble, and that is the big question. All other ethnicities unfortunately get grouped into either black or white or dark or light. That is something that we leave up to you to design.

Offscreen: Has anyone raised that as an issue, that there aren’t any other ethnicities?

KH: It was intended for there to be other ethnicities originally but it ended up being a question of practicality. We could not get good actors under “X” other ethnicities within our time frame. We thought of some people but we just could not get them. It became black and white for practical reasons.

Offscreen: In the film’s scenario, geopolitically, Africa would become the first continent to die… and other white nations might survive because they have so much more “writing material!”

KH: But then possibly… a poem does not have geography, necessarily. It is also a fantasy world and maybe things have become more globalized, more integrated, prior to this apocalypse.

Offscreen: To confess, the first time I saw this movie on video I had trouble understanding the voice-over. Maybe it takes a few viewings to understand the function of the voice-over. To me the images are of one piece. There is no difference from the first to the last in terms of the texture and the tone, whereas the voice-over is different. Sometimes it is on, some times it is not; sometimes it is pragmatic and narrational and other times very poetic. So it takes a bit of adjusting.

KH: It is a different kind of movie, for sure. I think it would have been boring if it was just the same thing. The voice-over was always meant to be something that you had to pay close attention to.

JF: It was really like having the two levels working independently yet complementing each other. We did know this could be a problem for an audience, the concentration and having to link the elements but at the same time it is OK if you do not get it. Maybe at the end you connect the dots and get it, or you watch it a second time. This was something we felt it definitely needed to make it more dynamic, to enrich what we wanted to get at.

KH: Both elements do come together at the end. It is very important for the film that during the process of watching it the first time you wonder about what is going on, but if you see it two or three times suddenly you understand what this world is and you get more into the beat of thing. Certainly the voice-over and the images were separate from the beginning, then the idea was to have them slowly come together, not necessarily into a logical mold but an emotional mold.

Offscreen: One of the connections I made to myself is that the voice-over narrator is a character and is part of that world where the poeticism is something they are doing to make sense of the world or to adjust to it. But the first time I saw it this omniscient, poetic narrator felt forced and sometimes too powerful for the images. But by the second, third, and fourth time she became a character.

KH: She was always meant to be a character in the film. She is the last one who can speak. It was meant to be part of the dual narrative where you have the consequences of a world and we have a history lesson at the same time of what this world is. But not necessarily one presented before the other. They are both being presented at the same time, which is one of the new and different things we are trying to do with the film, and maybe people are not used to seeing that.

JF: Some people told us that it would have been more easily understood or accepted if the voice-over was male, because they could have related it to the main character because there is this function right at the beginning where people do not know who that voice belongs to and that makes some people very reticent. But at the same time we really want to have that effect of a disconnect.

Offscreen: How did you direct the actors since they are not speaking?

JF: We had a meeting before shooting so that they could understand their characters. The parts were very difficult physically and you need a certain concentration for sure so, but I do not think they were very difficult parts to play. All the actors did begin with a sense of their character and what they should do and after that it was more on the set giving them the choreography, the acting and after that it was up to Karim because he was behind the camera telling them what to do.

KH: Yes, when you have physically difficult elements you then have to become very technical with your instructions. One of the things is that there are emotions that are easy to understand in the film. In order to play their role they did not need to know all of the political and metaphorical possibilities but just to feel an emotion. I think everyone has loved and lost and had the sense of nostalgia and sadness.

JF: You are the messenger of love… be strong!

Offscreen: You mentioned this earlier, but did you have the music on during the set?

KH: Yes sometimes but the rain and the rain machines were very loud. It was a miracle I did not lose my voice because of me shouting directions with the rain machines and the camera noise.

Offscreen: What was of the shooting ratio?

K: Five to one. We used Fuji film, very good film. And we used an Arriflex 3 camera, an MOS (without sound) camera because there was no live sound.

Offscreen: How was the post-production done? Was it edited the old way?

KH: No I stopped doing that. It was done on an AVID. I don’t think I will ever be able to cut a movie on film again. We cut it in one day and then went back to tweak a few things.

Offscreen: So it was transferred to digital and then you added sound?

KH: Yes we did everything on the AVID. We put most of the sound on it in one day too and recorded the voice-over after with Pascale Montpetit. You take the files from the AVID and using the edge numbers you cut the negative and do an answer print.

Offscreen: How long did all the post-production work take?

KH: We had to take a break because we did Ascension in the middle of it so we got our print after in August, 2001.

Offscreen: Do you and Julien plan to work together in the future?

KH: Probably not as co-directors but certainly in terms of producing films together.

JH: We have our own production company called Screen Machine.

Offscreen: Well I hope you all the best with your future projects together.