Warren Kiefer: The Man Who Wasn’t There

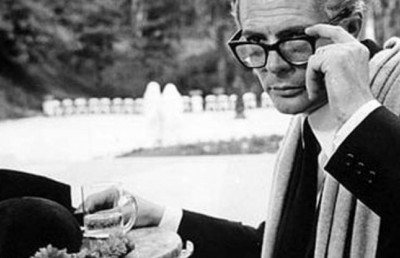

He wrote seven novels, directed at least three films and scripted “perhaps twenty more, some forgettable and most forgotten,” to quote his own words. Donald Sutherland, who was one of his best friends and even named his son after him, pictured him as “a lovely cigar smoking whiskey drinking mystery writing rogue of a man.” Yet, if you digit the name “Warren Kiefer” on the Internet Movie DataBase search tab, you will be redirected to a page stating that Warren Kiefer was just a nom de plume for Italian filmmaker Lorenzo Sabatini. The more you search on Kiefer on the web, the more you will find this very same notion repeated over and over. Which is quite amusing, since Lorenzo Sabatini did not exist in the first place.

So, what we have now, according to the world’s most complete database plus thousands of other sites, is a real man – a writer, and a filmmaker – being cancelled and overtaken by his alter ego. Imagine a parallel universe where Stephen King was an a.k.a. for Richard Bachman, or that the name “Jorge Luis Borges” was just a pseudonym conceived by Mr. Honorio Bustos Domecq. It’s a curious paradox, which perhaps says something about our world and the way we are living it, on the overload of information we are presented with in today’s “computer age,” which we are often only too glad to embrace without any critical distance. If the IMDb, or Wikipedia, or Google says so, well so be it. That’s ipse dixit for the third millennium.

So, how did all this happen? How did Warren Kiefer disappear, and let Lorenzo Sabatini take over? It’s a story that deserves to be told.

Mystery Man

Warren D. Kiefer was born in New Jersey in 1929. He was educated at the University of New Mexico, and the University of Maryland, where he also served on the faculty. His longtime friend Paul C. Mims recalls: “Warren and I first met in the autumn of 1949. We were students at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, I a 26 year old grad student from the University of Wisconsin, he a 20-year old under graduate from the Chicago suburbs. The Kiefer I knew was 20 years old, of medium height; say about five-foot eight inches tall, weighing approximately 160 pounds. He had a well muscled frame. His hair was light brown, close cropped but given to being wavy. Although not a rich boy he was from the upper middle class and used to the “good life”. Even as an under graduate he had extravagant tastes for food, liquor and girls. One of the great dilemmas in his life was how to combine both the “good life” and the artist’s bohemian life style. You see, one part of Kiefer, although quite capable of performing in the world of public relations and advertising, loathed its suffocating, mundane ethos. [1]

Kiefer loved all things literary. For a time he was an editor of the university literary magazine, The Thunderbird. According to Mims, “he had a romantic concept of the writer’s life and a naïve fancy that just over the horizon was the Promised Land.” His heroes were Hemingway and Francis Scott Fitzgerald. Mims and Kiefer were also close friends with another New Mexico graduate: Edward Abbey, who would become one of America’s most accomplished writers and whose 1956 novel The Lonely Cowboy [2] may have influenced Kiefer’s later works as scriptwriter and novelist. During his graduate years, however, Kiefer didn’t show any particular interest in movies. “Not until several years later, when he was doing public relation in Kalamazoo, Michigan” Mims recalls, “did he mention possibly writing a script for a film.” It was, to be precise, a documentary about guided missiles – not exactly Citizen Kane, that is.

In 1954 Kiefer married Ann, a girl from Kalamazoo, and enrolled as a graduate student at the University of Maryland. His intent was to take a Master of Arts degree in South American History. In the meanwhile he was made an Instructor and assigned two classes – one in photography and the other in Journalism. Warren soon became bored and resigned. He and Ann headed to New York City.

Funny enough, Kiefer’s tendency to use pseudonyms was evident since his very first novel. In 1958 Random House published Pax, written by “Middleton Kiefer,” an alias for Warren and his colleague Harry Middleton. A hard-boiled novel about “false promises and misleading advertising in the pharmaceuticals business,” as one reviewer put it, Pax benefited from the authors’ previous experience as a PR man for Pfizer. It’s the story of a huge pharmaceutical company, Raven, releasing an antihistamine tablet named Sneezone which has the side-effect of lulling people into a state bordering upon blubbering idiocy. Since Sneezone has been approved by the Pure Food and Drug investigators for over-the-counter sale without a prescription, Raven plans – by renaming it Pax, “the peace of mind pill” – to by-pass the prescription requirement for genuine tranquilizers and steal the market. What happens thereafter is, to quote another reviewer, “like the results from lighting a match to a pile of Chinese firecrackers.”

As Kiefer himself admitted, “Pax was written to pay for Alden, and it has. [3] Alden was Warren and Ann’s son, born in that same year, 1958. Kiefer told Paul Mims that he and his wife were planning at least two more children, therefore “there will have to be at least two more books, and then I suppose there will have to be a trilogy to put them all through college.” It didn’t go that way. As Mims recalls, suddenly Warren apparently dumped everything – wife, child, job, the lot – and made a run for the Promised Land.

Kiefer’s Promised Land turned out to be Italy. He relocated to Rome, where he carved himself a niche in the boiling cauldron that in those days was Cinecittà. Due to production facilities and costs, the so-called “Hollywood on the Tiber” became a powerful magnet for big time production and small ones alike, paving the way for a US-based community that savored the delights of “La Dolce Vita” and tried to make some money in the process.

Nineteen-sixty three was the year Kiefer made the big jump and had the chance to direct his feature film debut. It was quite a lucky combination of events, in which a big part was played by 30 year old, New York-born Paul Maslansky. “We met in Rome when he was production manager on a hokey Irving Allen epic called The Long Ships, being shot in he Cinecitta tank” Kiefer explained. “I was working the Middle East and Africa as a director-producer of TV Specials and documentaries.” [4] Kiefer shot a documentary for Esso in Lybia, but it’s likely that his experience in Africa also comprised a trip to Congo, as his 1972 novel The Lingala Code – set in the period after the killing of Patrice Lumumba – opens with Kiefer’s statement that “The Congo background is represented substantially as it was during the author’s time there.” He and Maslansky met at the Cinecittà tank, where Kiefer was shooting additional footage for his Esso documentary: they liked each other, got along well, and talked about making a movie together. According to Maslansky, Kiefer had married again at that time, with a beautiful Argentinian woman. His former self – Kiefer the businessman, trying to make ends meet and struggling to be a writer – had been left behind, and so his first wife and son. The new Kiefer, writer and filmmaker, was born.

In those years, after the success of Hammer Films Horror of Dracula (1958), America rediscovered horror movies. Universal picked up the Terence Fisher film, which was a surprise hit, and soon every independent U.S. distribution company was striving for low-budget horror flicks. Italy was quite a profitable source, after the success of Mario Bava’s Black Sunday (La maschera del demonio, 1960), which had been picked up by AIP. Many Italian horror films – which did very little at the domestic box office – ended up overseas: not just Bava, Freda and Margheriti’s classics, but also obscure low-budget flicks such as Piero Regnoli’s Playgirls and the Vampire (L’ultima preda del vampiro, 1960) and Antonio Boccacci’s Tomb of Torture (Metempsyco, 1963).

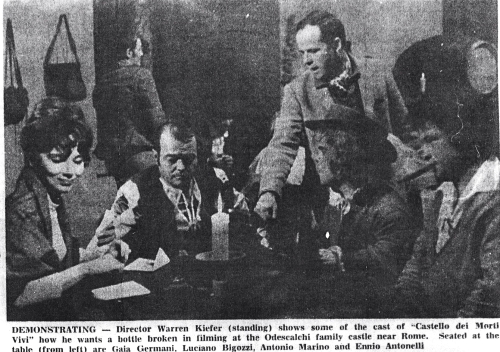

That’s how Castle of the Living Dead (Il castello dei morti vivi) was born. Kiefer provided a script about a bunch of street comedians who, in early 19th century, are summoned to the castle of Count Drago, who has perfected a rather unnerving embalming method and is looking for human beings to add to his collection, while Maslansky acted as producer. “We both wanted to make a feature, and Rome was a good place then to try. We each put up $10,000, plus my script” Kiefer recalled. “With those elements we contacted Chris Lee for 10 working days, and shot the film in five weeks at a splendid old castle [the Odescalchi castle] overlooking Lake Bracciano.” [5] A few scenes – which would provide for the film’s most memorable images – were shot at the Parco dei Mostri, Bomarzo.

So, why did Mr. Warren D. Kiefer, U.S. citizen, disappear from sight and become Lorenzo Sabatini? The name was made up by Kiefer, paying homage to Italian mannerist painter Lorenzo Sabatini (1530-1576). It was economically convenient for Warren to pass as an Italian, and for the film to receive law subsidies according to Italian cinema laws. “Angelo Rizzoli’s Cineriz came up with the main financing, and qualified the film as an official Italo-French co-production. This complicated my credit because to receive state subsidies, an Italian director was required,” Kiefer explained. “Thus, the Italian version of the film carried me only as scriptwriter and story originator, listing “Herbert Wise” as the director. “Wise” was an American-sounding pseudonym registered in Italy by my first A.D., Luciano Ricci. In my Cineriz contract, however, my name had to appear full card, last credit, as sole director on ALL other versions.” [6]

A comparison between different prints of the film confirms Kiefer’s words. On the Italian language copy [7] immediately after the title, a card says “un film di Warren Kiefer” (a film by…), but in the end another card says “regia di Herbert Wise” (directed by…). Whereas on the English language print, script and direction are credited to Warren Kiefer, while Maslansky is credited to co-writer. The name “Herbert Wise” does not appear nor does Luciano Ricci. It must be noted, however, that ??Castle??’s assistant director Frederick Muller states that Ricci never showed up on the set.

However, in Italian movie industry of the period it was a common practice for filmmakers to use foreign pseudonyms. Riccardo Freda repeatedly claimed that he was the first to do this when, after I vampiri??’s commercial failure, he signed his next horror film ??Caltiki the Immortal Monster as “Robert Hampton.” Italians, he used to say, wouldn’t pay the ticket for a horror film made by an Italian filmmaker, because they thought the horror genre was a British thing. That’s why many started thinking that the name “Warren Kiefer” might actually refer to an Italian filmmaker. Where the devil cannot put his head, he puts his tail: according to a publicity article on a movie magazine, at the time of ??Castle??’s release, the directors were “two young Italian filmmakers, Luciano Ricci and 32 year old Lorenzo Sabatini, born in Florence.” Perhaps the unknown writer simply took this bit from film’s press kit, or just made it up. However, hence came the notion that Sabatini was an Italian director born in 1932, whose pseudonym was Warren Kiefer, which can be found on Italian film dictionaries and reference books. [8] At the time of the film’s release, however, Italian reviewers usually didn’t seem to care who the director was. In a rather comical review, an unnamed film critic on La Notte even identified Herbert Wise with Riccardo Freda, writing: “Bomarzo is one of Central Italy’s architectural wonders […] Riccardo Freda degraded it to the setting of a bad vampire movie […]. Clumsily directed by the filmmaker, who this time is hiding under the fraudulent pseudonym Herbert Wise (previously it had been Robert Hampton) Philippe Leroy and Gaia Germani try their best to look terrorized […].”9 The one exception was the reviewer on La Stampa, who wrote: “Signed by Herbert Wise, the pseudonym of Italian Luciano Ricci (such mysteries are typical of French-Italian co-productions) the film was actually directed by an American, Warren Kiefer, who also wrote the story and screenplay.” [10]

Castle of the Living Dead was shot in 24 days on a cost which Kiefer recalled as approximately $ 135.000 dollars ($ 116,000 according to an article on the Daily American, [11] while Maslansky’s approximation was 125,000). Maslansky and Kiefer managed to average four minutes of film on the screen each day: an impressive achievement, even though something rather common in the world of Italian b-movie industry, considering that Riccardo Freda’s I vampiri was shot in 12 days, not to mention Roger Corman’s 3-day wonders. Each night after shooting they hurried to Rome to watch the rushes of the day’s filming, selected what they wanted and were on the set the following day at 7 a.m.

The dynamic duo devised all sort of speed-up techniques, no doubt advantaged by the fact of shooting most of the film in one location. They devised a floor plan of the Odescalchi castle so as to shoot in one room and then in the next; a second set was ready to go at all times so that as soon as one scene was completed the next would be ready (or in case something wouldn’t work on the first set); filming most scenes in one take and getting three different shots (short, medium, long) simultaneously. To save time, Maslansky and Kiefer gave up their idea of recording an original sound track. “Changes in the cast which brought in several non-English speaking actors made this impossible, and even if it hadn’t the acoustics of the castle would have, said Kiefer. And getting original sound wouldn’t have been as time-saving as the moviemakers at first thought.” [12]

Another mystery regarding Castle of the Living Dead – centers on the entity of the contribution to the finished film on behalf of a then unknown, nineteen year old Brit by the name of Michael Reeves, who had become friends with Maslansky on the Yugoslavian set of The Long Ships, where the former worked as production assistant. Struck by the young man’s enthusiasm, Maslansky hired him on Castle. Reeves would make his own debut as a director the following year, on another Maslansky-produced little horror movie shot in Italy and starring (well, not quite so) Barbara Steele, She-Beast (Il lago di Satana, 1965). [13]

During the years, Reeves’ work on Castle of the Living Dead has been wildly overpraised. Italian prints of the film do not even credit Reeves’ name, who is listed as a.d. with Fritz [Frederick] Muller on the American International Television English language print. Yet rumours that Reeves had been the true director all along would spread. In his celebratory piece In Memoriam Michael Reeves, [14] written soon after the young director’s premature death, Robin Wood claimed that Reeves had shot all the sequences at the Parco dei Mostri, while according to others, Kiefer fell ill after nine days and Reeves took over the whole production. On the revised edition of his classic book on English Gothic cinema A New Heritage of Horror, David Pirie writes: “Maslansky corrected this for me while I was writing the first edition of Heritage, explaining it was quite untrue. Reeves remained on the second unit for the entire picture, but the work he was doing with a scratch crew turned out so much better than Kiefer’s that his contribution was enlarged and he was allowed to make some additions to the script, including the introduction of a rather Bergmanesque dwarf.” [15]

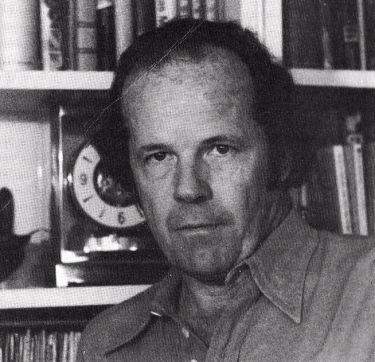

However, this contradicts what Maslansky stated in a 1999 interview, that the dwarf character was planned since the beginning: hoping to find an English-language speaking little person for their film, Kiefer and Maslansky flew to England to visit Billy Barty’s circus, but to no avail. One night they went to see a Lindsay Anderson’s Royal Court production of Spoon River Anthology, where they spotted an incredibly talented young man, tall, lanky and with a prominent Adam’s apple, who played five or six roles in the play. They paid him a visit backstage and asked him if he wanted to make a horror movie in Italy for 50 bucks a week. The young thesp accepted. That’s how Warren met one of his closest friends, Donald Sutherland, who would pay homage to him by naming Kiefer one of the twins his girlfriend Shirley Douglas gave birth to a couple of years later.

According to Benjamin Halligan, “Back in Rome, Maslansky had advertised for an actor of restricted growth for the role of the dwarf and fifteen arrived outside his flat on the morning of the audition. The first was called up (from the flat window) and, after four storeys of stairs and a disconcerting amount of time later, Anthony Martin arrived in a state of some physical exhaustion. Maslansky was mortified and to save further embarrassment awarded Martin the part. Martin, a tobacconist and part-time actor, would go on to appear in Corman’s The Masque of the Red Death, Horror Hospital, Vampire Circus (as Skip Martin) and Fellini’s Casanova among many other uncredited roles.” [16] Actually, the diminutive actor was an Italian man with a very similar name, Antonio De Martino, not the English-born Anthony “Skip” Martin. De Martino appeared in several other Italian films, including Piero Regnoli’s erotic fairytale La principessa sul pisello, where he plays one of the seven dwarves. [16]

While it is true that Jim Duncan’s piece on the Daily American mentions “a second unit under the two assistant directors filming less important action while the main crew was at work on another scene,” conceived in order to create a speed-up technique, Kiefer’s assistant director Frederick Muller was adamant with this writer that all the film was shot by Kiefer without Reeves ever being present. Kiefer himself, in a 1990 letter to U.S. film critic Steve Johnson, stated that “Michael Reeves hung around as an unpaid gofer during the production and had nothing whatever to do with the direction or anything else. He was English, rich and bright, and later went on to make one or two films with his own money before dying of a drug overdose.”

It’s likely Maslansky asked Reeves to shoot a few missing shots without the cast being present (for instance, shots of a carriage in the woods). As Benjamin Halligan puts it in his excellent book on Michael Reeves, “Mike oversaw some pick-ups, cutaways and, once principal photography was complete, missing shots. In some circumstances this would have been considered “Second Unit” material – but nothing that would ultimately make for any discernable authorial imprint on the finished film.” [17] Later on, Reeves would initially talk up his involvement in Castle but, as Halligan recalls, “only occasionally referred to this period as one of ‘some rewriting’ on a script that was being made by a director friend.” [18]

In his mammoth book on Mario Bava, All the Colors of the Dark, Tim Lucas reports Luciano Pigozzi’s assertion that Bava worked on Castle of the Living Dead based on an interview he did with the actor:

“Another time, he [Bava] was up on the mountain, and asked for three or four white sheets – I don’t know what for – and he painted. The scenery was very bad, but after he made the special effects… my God! You could see a ship, all the time making with this special glass, and you see the ship on this postcard – and he put it very close to the water, and you could see this ship going up and down, up and down, and afterward, it disappeared.” Which film was this? It was, it was… Il castello dei morti vivi. The Castle of the Living Dead. Bava worked on that film, too? Yeah. He came to make that scene, that special effect.” [19]

As anybody who has seen Castle of the Living Dead can agree, there are no scenes featuring ships. It’s likely Pigozzi got confused with another film on which Bava worked on the special effects, yet Lucas takes his words for granted, concluding that “it is possible that Bava’s effect appeared on the periphery of a scene and would only be visible when the film was shown in its correct 1:85 ratio” [!!!] or perhaps it didn’t make the final cut, and feels the need to devote a full three page to Kiefer’s film (which on a 1100-plus page book isn’t that much, but anyway….). Had Lucas bothered to dig a litttle deeper, he may have changed his mind. When asked about Bava’s contribution to the film, Frederick Muller has no hesitation whatsoever. “Certainly I don’t remember Mario Bava coming to the set ever. And I should know because few years later I produced a film directed by Mario Bava [Muller was production manager on the additional scenes Bava shot for Alfredo Leone on what would become The House of Exorcism]. No, this is pure invention… I wonder why people make such things up.” [20]

Lucas also states that Kiefer was actually a pseudonym of Lorenzo Sabatini, and goes even further, developing Pirie’s and Wood’s theory that Michael Reeves shot a portion of the film: “Michael Reeves’ specific contributions to the film would appear to include the scenes involving Dart, such as the gallows skit, the tavern fight, the scaling of the castle wall to Laura’s bedroom window, and his death-by-scythe. […] Another patently obvious Reeves contribution is the film’s opening narration […] which shows an attention to historical timing extremely uncharacteristic of Italian horror, and strongly parallels the opening narration of his final, and finest, film Witchfinder General.” [21] The least said, the better.

The film’s Italian-language script, conserved at Rome’s CSC, titled Il castello dei morti vivi – House of Blood (almost 200 pages long and with a timbre dated April 13, 1964 – could be misleading. First of all, one notes the presence of a voice-over (absent from the final film) of the dwarf Dart (who will become Pic in Italian language prints) which gives the proceedings an almost picaresque tone, and further dismisses Maslansky’s confidences to Pirie, as the dwarf character was obviously a central element of the film since the very beginning. The script – which is very precise in specifying camera movements and angles in almost every scene – displays a number of differences from the final film. All the scenes set in Bomarzo are missing, and the action takes place almost entirely in the castle. What’s more, the old hag who lives in the “Mouth of Hell,” played in the film by Donald Sutherland, is absent. According to Frederick Muller, this was an embryonic version of the script, whereas the ones given on the set already included the scenes at the Parco dei Mostri as well as Sutherland’s second character. It must be excluded, then, that Kiefer improvised new scenes during shooting: it’s likely that he and Maslansky visited Bomarzo while scouting locations, and that the director added a few more scenes in a last-minute rewriting before shooting started in order to take advantage of such a fascinating set. Muller also confirms that all the scenes in Bomarzo were shot by Kiefer alone. [22] The script also contradicts Mel Welles’ assertions, as reported by Halligan: “during post-synch in Phono Roma, a furious Lee discovered that there was no soundtrack at all, and that all the continuity sheets had been mislaid. Fireworks ensued, but Paul [Maslansky] won him over and the film was dubbed in its entirety as well as possible. […] Mel Welles, who oversaw the post-synching, claims the lost continuity sheets was partly a ruse to improve the dialogue.” [23] Yet what can be read on the script is virtually identical to what can be heard in the finished film.

Other differences are the names of a number of characters (Count Drago is named Baron Ippo, his servant Hans is Fausto) and, most remarkably, the ending, which is much more humorous – and better – than the definitive one. After Baron Ippo has accidentally died, transfixed by the sword held by one of his human statues, the dumb Sergent Pogue and his colleague show up and arrest Laura and Eric, the two surviving actors, for the baron’s murder; then (while outside Dart helps the prisoners escape) Pogue and his companion drink a toast with the Baron’s cognac, unaware that it’s actually the embalming fluid, thus getting immediately petrified.

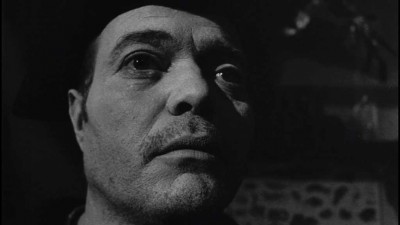

Beautifully photographed by Aldo Tonti and starring Christopher Lee (looking less bored than in his other Italian forays of the period), Philippe Leroy and Gaia Germani, plus a few Italian character actors (including Luciano Pigozzi and Ennio Antonelli), Castle of the Living Dead was a modest success in Italy and a rather profitable entry in the U.S. horror market. However as Kiefer stated, “the dividend for me on Castle became my enduring friendship with Don Sutherland.” The debuting Canadian actor slept at Kiefer’s home during shooting and played two roles in the movie: the dumb, self-important sergeant Pogue and an old ugly witch, in keeping with the mood of the film.

As Steve Johnson brilliantly synthesizes in an in-depth essay on the film [24] – Castle of the living Dead shares several stock characters (or “masks”) with 17th and 18th century “Commedia dell’Arte”: the protagonists are specialized in a variation of a classic 17th century performance starring Harlequin, who tricks his own executioner into hanging himself in Harlequin’s place, and the plot of the film itself unrolls as a variation of a classical “Commedia” play. Philippe Leroy and Gaia Germani embody the figures of Harlequin and Columbine beyond their theatrical roles, the folly Sergeant Pogue is reminiscent of the fearful and pompous Captain and the awkward Hans (Mirko Valentin) is the zanni, the antagonist’s servant whom Kiefer brings back to the original demonic figure, while count Drago is a more malevolent and less luxurious Pantalone, the elderly antagonist.

The plot broadly follows the plot of the Commedia dell’Arte as well: at the center of the story there are two opposing male figures (evil Count Drago and clever hero Philippe Leroy) fighting for a woman, who passively suffers the advances of the hero as the attentions of the villain, and in the end, while the two contenders are fighting for her, they narrow the aphasic Columbine into a corner, leaving the stage to the men, just like in a commedia. In the end Drago suffers the inevitable retaliation, accidentally ending up petrified as his own human statues: a bizarre accident which recalls Harlequin’s play at the film’s beginning, where the hangman falls victim of his own instrument. It’s no wonder Kiefer revealed that he had originally written Castle of the Living Dead as a horror comedy, but Italian financers asked him to play it straight, making it into a “fairy tale for grownups.” [25]

Although the Daily American announced the director’s next film as a western called The Outrider, to be shot in Lybia in November ’64 and co-produced by Kiefer himself, the project never materialized. Without a doubt, the American filmmaker was a victim of the industry crisis that since 1963 displayed the economical fragility of many small production companies that specialized in low-budget flicks. As film historian Simone Venturini wrote, “the extreme fragmentation of production companies, the increased production costs, cinema’s progressive loss of centrality compared to other entertainment activities and the companies’ recurring economical speculations” [26] are all factors that made many small fish sink in the troubled sea that was the Italian movie industry of the period.

Kiefer’s subsequent works were mostly screenplays for other directors, which were basically comprised into the western genre, which he had always loved. In 1950 Kiefer wrote a short story on Billy the Kid, and eventually tried his hand at it as a novelist, with Outlaw (1989). While he is credited on Beyond the Law (Al di là della legge, 1967), starring Van Cleef and Stander and directed by Giorgio Stegani, [27] there is no trace of him in the credits of the little-known Jessy non perdona…. Uccide a.k.a. Tierra de fuego (1965, known in the U.S. as Sunscorched), directed by and starring Mark Stevens and Mario Adorf, which he nevertheless claimed as based on his own script. [28] Another Kiefer-penned western was the dreadful The Last Rebel (1971), directed by Denys McCoy, starring former football star Joe Namath and Jack Elam and graced by an unbelievable rock score by Ashton, Gardner and Dyke, and featuring keyboardist Jon Lord of Deep Purple fame.

In his correspondence with Steven Johnson, he claims having directed “half a dozen films after Castle??” and mentions scripts “for perhaps twenty more,” adding that “all this work was done in Italy and various Italian directors got the credit (because under Italian subsidy laws the producer could only collect if the film was signed by an Italian) while I got the paychecks.” This makes things even more cloudy, as Kiefer’s official output as a director includes only two more titles, the idiosyncratic film noir ??Defeat of the Mafia (Scacco alla mafia, shot in late 1968 but released only in late 1970) and the erotic Juliette De Sade (Mademoiselle De Sade e i suoi vizi, shot in 1969 but released in Italy in late 1971), [29] a spurious adaptation of De Sade’s work. It may well be that the number of films he scripted and directed was a creative addition by Kiefer’s part. After all, reading Kiefer’s own bio on The Lingala Code makes one suspect that the author had the same creative knack for mixing fact and fiction regarding his own life as he had for his novels. [30]

Kiefer’s following efforts behind the camera were nowhere near as successful as Castle. On the contrary, they remain barely seen as of today. [31] Produced by Kiefer for his own company Afilm (funded with Alvaro Alfredo Tassani on March 2nd, 1965, it apparently produced only this movie), the director’s second feature film had the shooting title Sulle tracce di Susan Palmer (On the Trail of Susan Palmer) and then Morte improvvisa (Sudden Death) but it was eventually released as Defeat of the Mafia. Curiously, it was initially conceived as an Italian-Argentinian co-production – which is interesting, considering that Argentina is the country where Kiefer would move to for the rest of his life. It gets even more interesting when one considers that the Argentinian production company which was to finance the pic was called “Alden Film S.A.C.I.M.” – Alden, like Kiefer’s first son… [32]

Furthermore, as usual the film’s official credits are nothing short of puzzling. On legal papers for Defeat of the Mafia deposited at the Ministry of Spectacle in Rome, “Lorenzo Sabatini” is credited as both director and editor (!), while screenplay is credited to Tassani and Marian Doebbeling. Yet it’s likely that these were only fronts and Kiefer himself wrote the script on his own, given the pic’s offbeat tone, including the use of hard-boiled first person narration. The name Lorenzo Sabatini pops up in the end credits as well, this time credited as camera operator, while editing is credited to Piera Gabutti. What’s more, the English language copy is “a Warren Kiefer – Norton L. Bloom production,” whereas Bloom is nowhere to be found neither on legal papers nor anywhere else.

Defeat of the Mafia is a weird little film noir about the search for a batch of heroin which disappeared in Rome before getting to its recipient, crippled mafia boss Frankie Agostino (Luciano Pigozzi). The courier, drug addict Susan Turner, delivers the stuff to her accomplice instead, and later is found dead. Narcotics agent Scott Luce (Pier Paolo Capponi) investigates, while a member of the Agostino family arrives in Rome, posing as Susan’s cousin, to find out what happened. The fact that this latter character is played with icy aplomb by Welsh comedian Victor Spinetti (A Hard Day’s Night) [33] showcases Kiefer’s idiosyncratic approach to genre, which is also evident in the film’s style and editing. Rhythm is fragmented, direction at times haphazard. The opening sequence jarringly mixes flashes from Susan’s happy past – photographs, the sight of a spinning wheel at a luna park – with the present, as simplified by a close-up of a needle, while many scenes are shot with a nervous, hand-held camera, as both a means to cut short on budget and schedule – quicker set-ups, no dolly or traveling shots etc., – and a stylistic trait to suggest a wild, unpredictable world.

Defeat of the Mafia opens with Susan’s voice-over, who soon turns up to be a voice from the dead, ??Sunset Boulevard??-style. “All of a sudden, I had the most interesting body in Rome” she quips. The off-putting use of voice-over continues throughout the film, as the dead Susan comments, contradicts, mocks what other characters say. It’s a rather intrusive trick – and totally absent from the Italian language print [34]– yet it’s not gratuitous at all. First, it shows how in his heart Kiefer was more a novelist than a filmmaker, constructing scripts as if they were books, with an elaborate domino structure (“Push one and they all fall down. But I didn’t know anything about that at the time” Susan mutters, and the image of a falling domino chain appears under the title) and labyrinthine plot. Second, it displays the director’s weird – and at times rather self-sabotaging – sense of humour.

Defeat of the Mafia often borders on the grotesque. In one scene Spinetti and Maria Pia Conte visit a funeral home to choose a coffin for poor Susan to be brought back to the States, and Kiefer displays the kind of macabre jokes as seen in the coffin exhibition sequence in Dario Argento’s Four Flies On Grey Velvet (1971). Another scene displaying an exhibit of sculptor John Dahlia (Néstor Garay) looks like something out of a Mario Bava film: Dahlia’s sculptures consist of mannequins arranged in macabre poses, handling knives or looking like dead bodies (and Kiefer plays on the analogy by showing a victim arranged just like one of the artist’s “masterpieces”), with arms and legs protruding everywhere. Kiefer plays – it’s dubious whether self-consciously or not – on Bava’s idea of dummies equal people and vice versa, but the way he depicts Dahlia is even more disquieting: the disgusting, obese gay sculptor who turns out to be a drug dealer is easily the film’s most impressive creation, especially in the scene where he strangles his partner in cold blood.

The way Kiefer portrays the art exhibition is even more interesting as it somehow gives us the director’s view on Roman high life. If the subjective wide-angle shots of the sculptor meeting a parade of grotesque ladies and gentlemen look like an outtake from Fellini’s Toby Dammit, Kiefer generally depicts Rome in a rather idiosyncratic way. Aside from the obligatory scene at the Leonardo Da Vinci airport in Fiumicino (which, since its inauguration in 1960 became a common sight in Italian films, giving them an international flair), Defeat of the Mafia is a far cry from the tourist-friendly Rome as seen by many U.S. filmmakers, and rather showcases a disenchanted approach to the Eternal City. A meeting between Luce and his informer takes place in a seedy corner near the Colosseum, between pools of piss and wild cats, while the ending is set in a catacomb, in a surprising, neat Gothic touch.

Kiefer’s third – and by all records final – film was Juliette De Sade, produced by Paul Maslansky’s wife Ninki. Starring Maria Pia Conte, Angela De Leo, John Karlsen and Lars Bloch, it is a contemporary variation on De Sade set in a context that plays like a sort of Psychedelic riff on La Dolce Vita, just like Radley Metzger’s Camille 2000 did with Dumas’ The Lady of the Camellias in the same period. It remains unseen by this viewer, to this day. In an interview on Italian mag Nocturno, Lars Bloch recalled: “We took a pianist who used to play in Trastevere, at the Scarabocchio, and asked him to write the score. Guess what his name was? Bill Conti! That was his very first score.” [35]

However, in the early ‘70s Kiefer’s work in the movie business was already a thing of the past. Nineteen seventy-two saw the release of his second novel, The Lingala Code, published by Random House. Dedicated to Don [Donald] Sutherland and written in Rome, the book is an engrossing spy/mystery story told in first person by a former embassy employee in early ‘60s Congo, who finds out there’s something wrong with the death of his longtime friend, assassinated in his bed by a thief who then commits “suicide” in prison. The title refers to a CIA code system disguised as a local Congolese dialect, which has a fatal importance in the plot. The Lingala Code won the prestigious 1973 Edgar Award for Best Mystery Novel, awarded by the Mystery Writers of America. [36]

Kiefer followed it up with The Pontius Pilate Papers (1976, Harper), a fast-paced adventure yarn concerning the recovery of recently acquired Roman scrolls – which are said to contain eye-witness accounts of the trial and crucifiction of Christ – stolen from a museum in Jerusalem, with the scene shifting from Israel to Venice, Paris, London and Oxford, plus theological undertones which predate Dan Brown by a few decades. Warren’s fourth novel The Kidnappers, published in 1977, was set in Argentina, the country where he had relocated after his Italian experience. Perhaps Argentina was a refuge to the “suffocating, mundane ethos” which he intimately loathed; it was also his second wife’s home country. What’s more, Kiefer’s knowledge of South American history possibly influenced his choice. He would spent the rest of his days in Buenos Aires, where he wrote three more novels.

Outlaw (1989, Signet), a western saga spanning from 1870s to 1968 which many reviewers favourably compared to Larry McMurtry and Thomas Berger, would prove to be his best work to date. It finally marked Kiefer’s return to his favourite genre. Next came the witty The Perpignon Exchange (1990, Donald I. Fine), billed as “a novel of International intrigue.” Its main character – a French/Palestinian man named David Perpignon, who is mistaken for the mastermind of a hijacking in Lybia – is a stateless person with a dual identity who survives through his skills and wit, a figure that somehow relates to Kiefer’s real self, including the joke on Perpignon’s surname, which David’s drunken father gave him after misreading the label of a Dom Perignon bottle. The book’s inner jacket features a more recent picture of a balding Kiefer, plus a brief resumé which describes the author as “a former Marine and commercial pilot who has worked as a television journalist, film writer and producer.” Note how the word “director” is absent.

Despite the mention of Kiefer working on a novel about the life and times of General Benedict Arnold, his seventh and final novel The Stanton Succession (1992, Dutton) was a thriller set among stockholders and legal sharks at Wall Street, and somehow similar to John Grisham’s works. Aside from the sparse clues to be found on these first editions, no other informations are known about Kiefer’s late years. It’s reasonably sure that he passed away in early 2000s, in Buenos Aires, but to this day I was not able to find when and how in local newspaper’s archive. It’s quite a fitting ending, after all: like a character from his novels, Warren D. Kiefer just disappeared, leaving behind a riddle of red herrings and quite a lot of people believing he was someone else. He would have loved it.

Very, very, very special thanks to: Alessio Di Rocco, Benjamin Halligan, Robert Monell, Frederick Muller, Pete Tombs. And especially Steve Johnson (who kindly provided me with his private correspondance with the late Warren Kiefer, the Delirious issue with his writings on Castle of the Living Dead and the Daily American excerpt) and Mr. Paul C. Mims, a true gentleman and a great friend of Kiefer’s, without whom this piece of writing would never have been made in the first place. This one’s for you, Paul.

Addendum (June 18, 2019):After writing this essay I managed to get in touch with a few more people who knew or were related to Warren Kiefer, and some more pieces of the puzzle have fallen into place. So, it seemed just right to add a post-scriptum for the reader.

The “beautiful Argentinian woman” Kiefer had married in Italy was Marian (or Mariana) Doebbeling, whose credit on the script for Defeat of the Mafia is in all likelihood a front for Kiefer. Mariana was of Argentinian origins and came from the Chaco region. Her family had made their money from cotton. During Kiefer’s stay in Italy he and Doebbeling lived ay Isola Farnese on the via Cassia, north of Rome. According to Mr. Keith Richmond, Kiefer was a close friend of Victor Wolfgang von Hagen, a noted explorer, anthropologist and archaeologist who wrote many popular books such as Highway of the Sun and Roads that Led to Rome. Von Hagen had relocated in Italy in the mid-1960s and stayed in Trevignano Romano, near Rome, on the lake Bracciano.

Mr. Thomas Holladay told me: “I knew Warren in Buenos Aires, 1986-90. I lost contact after that. He lived well in an apartment downtown and had a country place in Punta Del Este. He divorced the Argentine and was with a younger English woman, and had a son, Johnny, with her. He entertained generously and always had a passel of US press people in attendance. I never delved into his past. […] It was the period during which Outlaw was being published.” Actually, Kiefer’s third wife was an American woman named Ann-Marie. They had two children, Johnny and Kathleen.

Some time after writing the essay, I had the pleasure of getting in touch with Warren Kiefer’s daughter, Kathleen Alexandra Kiefer. She confirmed to me that her father died of a massive heart attack in 1995 in Buenos Aires. His ashes rest on a river bank in Northern Wisconsin, U.S.A.

Endnotes

1 This and the following excerpts come from the author’s email interviews with Paul Mims, July-August 2010. Mr. Mims kindly provided his private correspondence with Kiefer, which is referred to where noted.

2 Adapted for the screen by Dalton Trumbo in 1962’s Lonely Are the Brave, directed by David Miller and starring Kirk Douglas, Gena Rowlands and Walter Matthau.

3 Warren Kiefer, letter to Paul C. Mims, October 10, 1958.

4 Warren Kiefer, letter to Steve Johnson, July 24, 1989.

5 Ibidem.

6 Ibidem.

7 Released on dvd in November 2010 by Passworld.

8 See Roberto Poppi, Mario Pecorari, Dizionario del cinema italiano. I film (1960-1969), Gremese, Roma, 1993; Roberto Poppi, Dizionario del cinema italiano. I registi, Gremese, Roma 2002.

9 Anonymous, “Il vampiro di Bomarzo” [The Vampire of Bomarzo],La Notte, August 8, 1964.

10 Anonymous, “Dracula si rinnova: da vampiro a imbalsamatore” [Dracula updates: from Vampire to Embalmer] La Stampa, August 6, 1964.

11 Jim Duncan, “Horror-For-Fun Pays Off,” Daily American, August 30-31, 1964.

12 Ibidem.

13 Even though she is top-billed, Steele appears on screen for a minimum time.

14 Robin Wood, “In Memoriam Michael Reeves,” Movie, 17, Winter 1969/70.

15 David Pirie, A New Heritage of Horror. The English Gothic Cinema, I. B. Tauris, London 2008, p. 168.

16 Email to the author, November 2011.

17 Halligan, Michael Reeves, p. 41.

18 Ibidem.

19 Tim Lucas, Mario Bava. All the Colors of the Dark, Video Watchdog, Cincinnati OH, 2007, p. 575.

20 Email to the author, July 2010.

21 Lucas, Mario Bava cit.

22 Email to the author, January 2012.

23 Benjamin Halligan, Michael Reeves, Manchester University Press, Manchester 2003, p. 41, pp. 40-41.

24 Steve Johnson, “Italian American Reconciliation: Waking ‘Castle of the Living Dead,’” Delirious – The Fantasy Film Magazine no. 5, 1991.

25 Duncan, “Horror-For-Fun Pays Off.”

26 Simone Venturini, Galatea Spa (1952-1965): storia di una casa di produzione cinematografica, Associazione italiana per le ricerche di storia del cinema, Rome 2001, p. 30.

27 The fim’s opening titles credit the story by Warren D. Kiefer and the screenplay to “Mino Roli, Giorgio Stegani, Fernando di Leo and Warren D. Kiefer.”

28 In a letter to Steven Johnson dated March 1st 1990, Kiefer mentions “two westerns with Lee Van Cleef and Lionel Stander, another with Mark Stevens and Mario Adorf.”

29 The film was released in Uk as Heterosexual, in 1970.

30 In his bio for The Lingala Code, Kiefer claimed that he had served active duty with the Marines during the Korean War. As Mims recalls, “He was only in the Marine Corps for a few weeks before been discharged for medical reasons. The Korean War was fought in the 1950s, at which time both Keefer and I lived either in Albuquerque or in or around the Chicago area and saw each other from time to time. By 1953, both of us had moved to the East Coast, I to attend graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania and Kiefer to make a brief appearance at Quantico, Virginia as a Marine officer candidate.” Another misinformation in the bio has Kiefer claim that he studied at Andover, a private prep school for boys. “Kiefer did say his dad entered him there, but he claimed to have been kicked out for misbehavior,” Mims recalls.

31 While Defeat of the Mafia was released in homevideo and was shown on Italian TV in early 2000s, there are rumours of a Swiss VHS release of Juliette De Sade, which unfortunately this writer hasn’t been able to track down.

32 Alden Fims’ administrator was Armando Petruccelli. According to legal papers, the agreement between the two companies involved the production of two films: Defeat of the Mafia, with a majority Italian quote, and El asado, with a majority Argentinian quote. Budget for Kiefer’s film was 65 million liras (45.500,000 on behalf of the Italian society), with a five-week schooting schedule.

33 Spinetti’s is not the only odd choice in the cast, which features stage actress Carmen Scarpitta as a countess and Angela Goodwin as a U.S. vice consul, side by side with Italian B-movie habituées such as Luciano Pigozzi, Aldo Berti and Enzo Fiermonte.

34 The Italian TV print is also heavily cut. A long fight scene between Capponi and Agostino’s sidekicks is missing, as well as a rape/sex scene between Paolo Giusti and Micaela Pignatelli and another where Néstor Garay is in bed with two men.

35 Roger A. Fratter, “Lars Bloch – E il corvo disse a Caino…,” Nocturno dossier 62, september 2007, p. 65.

36 Other nominees were Five Pieces of Jade by John Ball, Tied Up In Tinsel by Ngaio Marsh, The Shooting Gallery by Hugh C. Rae and Canto for a Gypsy by Martin Cruz Smith.