The Vertical Topography of the Science Fiction Film

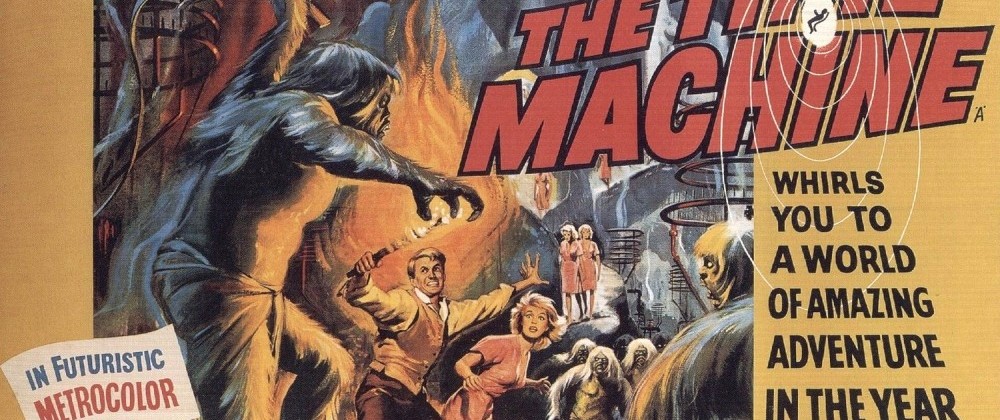

The study of genre looks for recurring tropes and patterns across like for like films, usually broken down into iconography (which includes visual style, conventions, props, characterization, etc.), or into what Rick Altman calls semantic (the surface elements such as iconography and conventions) and syntactic (the relational patterns in plot and theme that constitutes meaning). For years I have kept a running mental note of semantic instances in science fiction films where the physical spaces represented are cross-aligned vertically, that is where narrative action moves between up/down, above/below, high/low, skyward/earthbound, above ground/below ground. Once these instances became too many, in number and variance, I began to write them down and began to see parallels, similarities, and connections. One of the most striking connections is when the physical spaces represent a literal reflection of political and/or class distinction or some form of hierarchical stratification –a geo-political use of space and movement. This symbolic equation of physical distance with class representation is evident in some of the most seminal science fiction films of all time (and of course literature). For example, in Fritz Lang’s monumental Metropolis (1927) the slave-like working class live and work in the catacombs below the earth and the ruling class live high above in luxury skyscrapers. In George Pal’s adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine (1960) future society is segregated spatially between the violent, apelike Morlocks who live in the perpetual subterranean dark, and the peaceful all-blond Eloi, who live above ground. In Wells’ novel (but less so in the film) the two groups represent the evolution of the class system, with the Morlocks representing the working class and the Eloi the leisure class. Like Metropolis, the underground houses the machinery and technology necessary to make the leisurely lifestyle of the Eloi possible. Jump ahead to 1982 and another monumental science fiction film, Blade Runner (Ridley Scott), and you have a similar class division through physical, vertical distance. In this case the rich live high above in the ‘Off world’ and the working class and poor live down on a perpetually dark, wet, toxic earth. A similar inflection on the class system occurs in John Boorman’s Zardox (1971). Zardox takes place in the year 2293, after an apocalyptic cataclysm which has seemingly left the earth destitute. Barbarian foot soldiers (The Exterminators, the working class) worship a huge floating stone head called Zardox, which bellows orders to the Exterminators to kill the inferior scavenger humans, the “Brutals” (slaves). One of the ‘barbarian’ leaders of the Exterminators, Zed (Sean Connery), begins to question the social structure, and stows away inside the Stone Head while it is on one of its usual landings to fill up with harvest. The Stone head takes Zed into uncharted territory, flying over gorgeous, verdant countryside and then lands in an area called the Vortex where the Eternals, the elite ruling class, live.

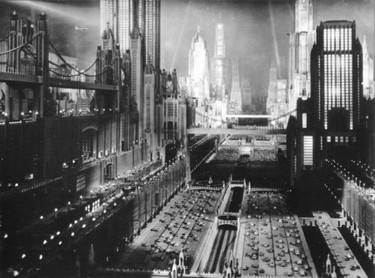

The workers below

The rich above, in Metropolis

The Morlocks

And the Eloi

The Flying Godhead in Zardox

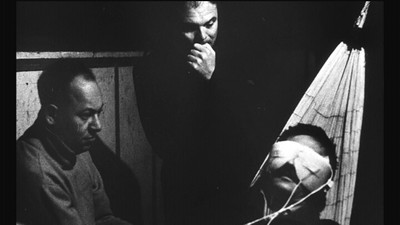

Plato’s Allegory of the CaveIndeed the image of a people or society living below earth level (as in Metropolis, Time Machine, La Jetée, Saving Grace, etc.) has its roots in Plato’s template for a ‘utopian’ society, The Republic, and the contained allegory of the cave. In this timeless allegory about Appearance and Reality a group of people have lived all their life chained in a cave watching shadows cast on a wall in front of them by things moving past a fire behind them. For the cave dwellers what they see in front of them, these shadows, is reality because it is all they have ever known. But when one of them escapes from the cave to learn about another reality above them they come to realize the difference between what appeared to be real and what is real (the Truth). In some respects Plato’s Allegory of the Cave has served as a template for much science-fiction: a society (or person) forced to live underground (or in a trapped society) and then realizes that there is another reality beyond their existence. We see this most clearly in Zardox, described above, but in many other films, like George Lucas’ THX-1138 (1971). In Lucas’ dystopia humanity lives in underground police-city states, until a man, THX-1138 (Robert Duvall), rebels. He first stops taking the stultifying drugs that make everyone passive subjects, then eventually escapes the ‘borderless’ prison into an unknown future. A similar narrative path takes place in Logan’s Run (1976, Michael Anderson), only the ‘cave’ in this case is a giant domed city that is cut off from the rest of the world. When citizens of this utopian prison reach the age of 30 they are “reborn” in a ritualistic ascent in a carrousel. The equivalent character to THX-1138 is Logan (Michael York), a ‘sandman’ whose job is to chase after 30 year olds who try to elude their fate by escaping the domed city (‘runners’), in search of a mythical world beyond called the “Sanctuary”. When Logan learns that these young people are being killed, he becomes a renegade and (with girlfriend in tow, like Duval), escapes to the splendorous sanctuary.

The underground survivors in La Jetée

Even Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979) has echoes of Plato’s “The Cave,” as the titular character defines his existence in the drab city outside the ‘zone’ as “like living in a prison.” Only when the three men, the Stalker, the Writer and the Scientist, pass into the physical space of the zone (demarcated by a shift to color) do they come to realize their ‘true’ selves.

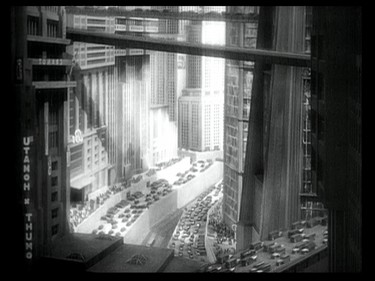

Vertical Movement as Utopia and SpectacleAt a purely visual level, this vertical stratification of space is an ideal way to exploit a certain aesthetic which is integral to the science fiction film, namely a mise en scène of extravagant art and set design, architecture and travel vehicles. Some of the most lasting imagery from Metropolis, Shapes of Things to Come (1936), and Blade Runner are the impressive aerial vistas of skyscrapers, connecting transport passageways, urban night lights, and futuristic advertisement.

Metropolis

Just Imagine

Much of this futuristic urban planning has its roots in developments like the art of Soviet post-Revolution Constructivism. In Constructivism art the euphoria of the Communist revolution (bolstered by propaganda) led artists such as Vladimir Tatlin, Leonid Pavlov, and Vladimir Krinsky to design experimental and utopian architectural designs and urban planning that were far removed from reality and appear science-fiction like even today. Architectural designs and drawings existed for celestial cities that would hover above ground. This euphoria stemmed from the artistic urge to replace the old Russia with the new. To quote Russian Futurist poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, “The twin fires of war and revolution have taken hold of our souls and cities. The palaces of yesterday’s pomp stand as burnt-out skeletons. The ruined cities await new builders….The revolution of content…is unthinkable without a revolution of form.” [1]

One of the most famous architectural designs of the period was Vladimir Tatlin’s “Monument to the Third International” (1918). The Monument was designed as an enormous spiral architecture, inspired by the Eiffel Tower, made out of steel, glass, and iron that was meant as a Monument to the Workers and the spirit of the Machine Age. The structure was intended to rotate at different levels, have suspended geometrical forms, house different venues and have a communication tower at the top of the spiral which would project communist slogans onto the sky. Intended to be twice as high as the Eiffel Tower, it was never built (scale models did exist), but you can see some of these ideas filtering down to Metropolis (the aerial passageways and floating geometrical objects) and Blade Runner (the celestial ‘off world’ society, the animated billboards projected against buildings).

Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International

Eiffel Tower in opening montage of La Jetée

The Eiffel Tower as an emblem of the Modern Age plays a central role in René Clair’s whimsical science-fiction fantasy, Paris Qui Dort (The Crazy Ray, 1925). A scientist invents a beam that stops time, putting all of Paris in a state of deep freeze, except for a group of five people and a worker who were atop the Eiffel Tower when the beam hit. Clair’s camera often films the sole people unaffected by the beam from the vantage of the Tower, looking down at the still city below. The camera also accentuates the distance and height with vertical movements down the Tower. The aerial views and movements from atop the Eiffel Tower encapsulate what J.P. Telotte describes as “[an] effort to explore the distances that attend the modern, technological world view” [2].

Atop the Eiffel Tower in Paris Qui Dort

While the Russian Constructivists dreamed of cities above ground, the mythology of the lost continent of Atlantis (also first envisioned by Plato) posits an advanced civilization living at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean, sunken by a violent earthquake (there are still people who believe that this is fact and not fable). In the Russian science fiction film Amphibian Man (1962, Vladimir Chebotaryov, Gennadi Kazansky) the myth of Atlantis is a strong influence. The reclusive Dr. Salvatore (Nikolai Simonov) lives in an ivory tower laboratory with his half-human/half-fish son Ichtyander Salvator (Vladimir Korenev). In a review written for my Fantasia International Film Festival 2009 report, I wrote, “[the son] had a fatal lung disease as a boy which the father cured with a shark’s gill transplant. The transplant gave his son the ability to swim underwater for long periods of time.” The successful operation on his son gives the doctor the idea of creating “a ‘classless’ utopian, underwater society by giving all humans a shark gill transplant!” [3] John Baxter describes the German Der Tunnel (1933, Curtis Bernhardt) as “a compelling picture of an attempt to drive a tunnel under the Atlantic, and its sets are among the most remarkable ever created for a science fiction film.” [4] In early versions of the Atlantic myth, based on the 1919 novel by Pierre Benoit L’Atlantide, Feyder’s (1920) and Pabst’s (1932) L’Atlantide the lost continent of Atlantis is not undersea but in the Sahara desert, while it returns to its proper underwater lair in the George Pal’s, Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961).

In the classic Forbidden Planet (1956, Fred Wilcox) an ancient, highly advanced future society, the Krells, designed their technology in miles of underground tunnels and cylindrical shafts. Made a year before, Joseph Newman’s Not of this Earth also deals with a dying alien planet, Metaluna, whose iconic looking aliens (their heads look like upside pear shaped brains) take refuge in elaborate underground rooms that house their sophisticated technology.

At times the vertical mise en scène I am according a thematic significance is simply a product of the adventurous spirit of exploration and colonial conquest that was typical of early science fiction. One of the masters of ‘adventure’ science fiction was the French writer Jules Verne. At least four of his most famous novels (all made into films) depict vertical movement from earth to below land, earth to sky, or earth to underwater: A Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864), From the Earth to the Moon (1865), _Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1869–1870), and Around the World in Eighty Days (1873). Alongside Vernes is American author Edgar Rice Burroughs, whose novel At Earth’s Core was made into a film in 1976 (Kevin Connor); and Wells’ novel The First Men in the Moon which was first made into a silent film in 1919.

In other instances the geo-political subtext associated with the science fiction films that I have outlined above is set aside for extravagant visual effects and one of the narrative constants of science fiction: space and interplanetary travel (Conquest of Space, 1955, Byron Haskin). As noted by Susan Sontag in her classic essay, “The Imagination of Disaster,” “Science fiction films are not about science. They are about disaster, which is one of the oldest subjects of art.” [5] In these dozens of cases the cinema frame becomes a playground for vertical movement. Any film where aliens attack earth will feature such movement, for example, Earth vs. the Flying Saucers (1956, Fred F. Sears), War of the Worlds (1953, Byron Haskin, 2005, Steven Spielberg), The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951, Robert Wise), Battle in Outer Space (1959, Ishiro Honda) The Mysterians (1957, Ishiro Honda), or Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977, S. Spielberg). In some cases the movement of flight (from earth to another planet, or the reverse) occurs as a revelation at the end of the film and holds more dramatic weight, as in Invaders from Mars (1953, Byron Haskell), Mario Bava’s Planet of the Vampires (1965), the Japanese Goke: Body Snatcher from Hell (1968, Hajime Sato)or Red Planet Mars (1952, Harry Horner).

Alien vampires target earth in Planet of the Vampires

On the other hand, there are also many cases where the ‘attack/invasion’ has a quasi political overtone –Communist infiltration/takeover, colonialism, anti-War message– as in many 1950s Cold War films, Godzilla (1956, Ishiro Honda), where the threat comes from below sea level rather than aerial, or The Thing from another world (1951, Christian Nyby) and its remake The Thing (1982, John Carpenter), where the threat also originates from below ground, from the alien ship buried underground; or the satirical found footage film from Craig Baldwin, Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies under America (1991), which uses clips from dozens of B-movies, horror and science fiction films to imagine an Alien colonialist empire, the Quetzals, living at the center of the earth. At the film’s core (excuse the pun) is a critique of US imperialist, disruptive foreign policy governing the Third World and Latin America. As Michael Zyrd notes, “As the film progresses, Baldwin’s allegory becomes clear: Quetzals stand in for communists, as the film suggests that American political policy was motivated by a racist, paranoid, and apocalyptic fear more appropriate as a response to a threat from reptilian space invaders than to the presence of democratically elected governments in the region. Just as George W. Bush employs the rhetoric of an “axis of evil” to vilify his enemies, so Baldwin suggests post-World War II U.S. administrations have literally demonized leftist governments in Latin America to justify covert operations, assassinations, support for military coups, the training of right-wing death squads, and human rights abuses.” [6] In a novel twist, in Val Guest’s Cold War The Day the Earth Caught Fire, the threat is not from a distant alien planet, but from human made nuclear interference (by the US and the Soviet Union of course) which causes the planet earth to pull out of its orbit and hurdle toward the sun.

Solaris, by Tarkovsky

In some of the more dramatic instances it is the camera which takes off in a vertical ascent or descent that delineates a sense of wonderment. One of the most profound examples is the finale of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972), where (MAJOR SPOILER if you have not seen the film) an aerial image of the central character seemingly back on earth pulls back to reveal the location as an island on an alien planet, Solaris. This ‘cosmic’ movement was inverted in Contact (1997, Robert Zemeckis) by having the movement at the beginning of the film, and the perspective start from an planetary view of the earth and then zoom out into the universe, only to end up in a human eye.

Opening shot from Contact

Vertical Space Below Ground ZeroPeople or society forced to live below ground because of an apocalyptical event (nuclear attack, nuclear contamination, destructive world war, natural catastrophe, etc.) is a common science fiction theme, already cited in a few titles above (Not of this Earth, Forbidden Planet). In La Jetée the remaining humans live below ground like moles and use a man’s memories to travel in time; in parts of the Planet of the Apes films humans (or mutations) live in what was the underground subway system; in the recent Canadian science fiction film Saving Grace (2010, Chris Pickle) a man named Clayton (Jason Barbeck) kidnaps an injured woman, Grace (Many Bo), from the hospital and keeps her imprisoned in his underground basement home because of his claim that the outside world has been devastated by a series of terrorist bombings that have made the air toxic to human survivors. But, is the outside world as unsafe and dangerous as Clayton claims, or his story a ruse to keep Grace confined? Clayton’s reliability underscores the central dramatic tension in the film. As viewer’s we have the same reason to doubt Clayton’s story as the skeptical Grace because there is little external evidence of Clayton’s claims, until the end of the film. Because of this doubt about what is real and what is an illusion, Saving Grace is yet another science fiction film that invokes Plato’s Cave Allegory. In many ways director Pickle’s mise en scène suggests such a reading, in the way he often places his camera looking through a wall-sized plastic sheet hanging from the wall of Clayton’s living space, which produces an unclear, ‘smeared’ visual field. Like Plato’s captive prisoners, Grace will only know TRUTH if and when she escapes from her dungeon prison into the ‘real’ world, a moment which results in a disturbing ending reminiscent of Night of the Living Dead (1968, G. Romero)

Saving Grace invoking Plato

In the recent post-apocalyptic/punk science-fiction film Bottled Fool (aka Hellevator), which was featured of Offscreen, a ravaged Tokyo necessitates city levels built below ground level, accessed by huge freight elevators. The film begins with a group of people entering the elevator at ‘Level 138,’ and then stopping at ‘Level 99’ (the Penal Colony) to pick up two violent convicts to transport to ‘Level 0’ (the prison). The convicts overpower their police escorts, leading to a tense, claustrophobic , and violent cat and mouse game between the psychotic convicts and the trapped passengers.

Outside…..

And inside views of the elevator in Hellevator

In Richard Stanley’s Hardware (1990) the earth is an arid and polluted desert wasteland, populated by scavengers and vagabonds. The central female character, Jill (Stacey Travis) is an artist who lives secluded in her high security apartment block. Even in the recent The Road (2009, John Hillcoat) the survivalist team of father and son seek a semblance of safety and domestic bliss by taking temporary refuge in an underground bunker.

Prison-like apartment and underground tunnel in Hardware

Vertical Distance as an Effect of the Mind

The Loneliness of space (Moon)

In some more subtle uses of vertical space/living, the film may not even feature any actual vertical space travel (or very little), but instead the gulf between earth and space is felt emotionally by the emphasis on a sparse mise en scène and character loneliness and isolation. In other words, the distance is both physical but emotional and psychological. The above mentioned Solaris (which reduces the space travel to one brief inconsequential shot) as well as its modulated remake by Steve Soderbergh, is an excellent example which has served as a sort of template for later more ‘contemplative’ and ‘somber’ science-fiction films. In contrast to the Stanislaw Lem novel (which begins on the Solaris space station) Tarkovsky opens with a long (45 minute) pastoral prelude on astronaut Kris Kelvin’s family dacha, which sets up the intense ‘nostalgia’ for earth, home and family that Kelvin will experience for the rest of the film. Made the same year as Solaris, Silent Running (1972, Douglas Trumbull) features a similar character isolated in space. Bruce Dern plays a glorified Park Ranger in custody of planet earth’s last vegetation, conserved in interstellar greenhouses. When he is ordered by the government to terminate the greenhouse he takes extreme measures to conserve earth’s natural heritage. He decides to kill his crew members and hijack the spaceship to spend the rest of his life in solitude floating in deep space tending to his plants. In Moon (2009, Duncan Jones) astronaut Sam Bell (Sam Rockwell) longs for the end of his solitary three year space so he can return home to his wife and daughter. The isolation begins to play on his fragile state of mind; he begins to imagine people on the ship, even his double, before coming to the realization that his (and our) version of reality was only a simulacrum. A similar sense of loneliness and thematic of cloning but with a more rigorous, Tarkovskian aesthetic, is played out in the outstanding Japanese science-fiction film, The Clone Returns Home (2008, Kanji Nakajima). In all of these films, the vertical gulf between space and earth may not be played out visually, but is nonetheless integral to the thematic shift to memory and nostalgia.

Alone in space (Moon)

At this point my essay has turned into (devolved?) a diachronic exercise in outlining both major and minor modes across what is an expansive element in science-fiction, shifting from a hierarchical use of physical space (rich vs. poor, working class vs. elite, mutants vs. humans) to an inescapable trope inherent to certain narrative ‘movements’ (earth to sky, earth to universe, outer space to earth). And while this may dilute my initial focus (the strict geo-political use of space in Metropolis, The Time Machine and Blade Runner) it opens the area up to more complex, and nuanced aspects of science-fiction and demonstrates that science-fiction can be more than ‘space operas’ or glorified action films. It also demonstrates a certain limitation in existing genre theory which attempts to separate semantic and syntactic elements because the use of physical separation and vertical movement, which can impact across many aspects of a film –art design, set design, props, camera movement, editing– can in one instance be nothing more than an aspect of spectacle (disaster from above/below, special effects) or an unavoidable convention (planetary travel, space flight), while in another instance be embedded in a film’s theme, meaning, or political subtext.

Endnotes

1 “Architectural Drawings of the Russian Avant-Garde,” Catalogue from The Museum of Modern Art, June 28-September 4, 1990.

2 J.P. Telotte, A Distant Technology: Science Fiction Film and the Machine Age, Wesleyan University Press: Hanover and London, 1999, p. 86.

3 Donato Totaro. “Science Fiction Soviet Style.” Offscreen. Volume 12, Issue 3, March 31, 2008.

4 John Baxter. Science Fiction in the Cinema. New York: Paperback Library, 1970, p. 37.

5 Susan Sontag, “The Imagination of Disaster,” Against Interpretation, and other essays. Dell Publishing, New York, 1961, p. 215.

6 Michael Zyrd. “Found Footage Film as Discursive Metahistory: Craig Baldwin’s Tribulation 99,” The Moving Image 3.2 (2003) 40-61