Town and Country –City Films and the Wilderness at FNC 2008

Tokyo, midday, the interior of a middle-class family home. The camera tracks right past the dining room table as a sheet of newspaper lifts from its surface and blows to the ground. A window has been left open with a rainstorm raging outside. The woman of the house rushes over to shut the door and mop up some water that has pooled on the hardwood floor. Then, as though called by something intangible beyond the edge of her domestic sphere, she looks outside for a moment – and opens the window again.

One of the highlights of this year’s Festival Nouveau Cinéma was Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Tokyo Sonata, a film that unfolds around a structured tension between domestic space and the world outside. An economic storm is sweeping through Japan, and a typical middle-class family tries to keep the turmoil of the world from crossing over the threshold into their home. Salaryman Sasaki loses his job. Too afraid to tell his wife and two sons, he continues to dress for work and leave the house every morning to hang out in a park where he, and others like him, gather with the destitute in the food bank line. He forbids his adolescent boy from taking piano lessons, but won’t admit to the economic reasons for his decision. Instead he expects his authority as head of the house to be respected without question. But the boy sneaks behind his father’s back, foregoing three months of school lunches to put the money towards lessons where he learns he is a child prodigy. Meanwhile his older brother runs off to join the American military, another act of defiance against the father who wants to keep the young man under his wing. Eventually Sasaki stoops to taking menial jobs, and when discovered by his wife the balance of power in the household is disrupted. From there things veer off in a bit of a strange direction: a hostage taking and car accident force the family apart, only to see them come back together under slightly suspicious circumstances…

Known for his masterful contributions to the J-Horror phenomenon and a favourite son of Montreal’s Fantasia genre-film festival, this year Kurosawa’s absence from Fantasia was keenly felt. After seeing the new film, it is clear that it wouldn’t have been as appropriate in a fantastical setting as previous Fantasia favourites like Cure or Séance. In Tokyo Sonata Kurosawa takes a couple steps back from the supernatural in order to focus on a family disintegrating at the hands of Japan’s social and economic difficulties. But make no mistake: there is real magic here, enough to warrant its inclusion as part of the Temps Zéro programming by Fantasia alumnus Julien Fonfrède.

Whatever one makes of the film’s ending, Kurosawa’s downplay of the overtly supernatural only emphasizes the strangeness that the cold reality of urban life can engender. Indeed, Kurosawa’s masterfully understated approach makes this film a real gem. Fans will recognize approaches to mise-en-scène, montage, and sound that are characteristic of Kurosawa’s previous work, set here a bit more simply than usual so that the richness of the film’s understatement might be elevated to a new level. As an example, consider Kurosawa’s recurring use of sudden moments of absolute silence. In his earlier films these moments of vacuum are always harbingers of supernatural forces at work, as though representing auditory portals into dimensions that occasionally break through into the one that we inhabit. These moments in his previous films have always seemed a bit forced to me, never quite fully integrated into the narrative fabric of their respective films. In Tokyo Sonata Kurosawa has finally found the perfect home for his interest in silence.

Throughout the film he plays with light and sound to control the viewer’s awareness of the world outside the family home, a world that calls his wife and kids out one by one, gradually breaking the family apart despite his efforts to keep the family unit contained. At key moments Kurosawa injects bursts of flashing light through the windows in the dining room and living room. We hear accompanying train sounds that suggest the lights are reflections off the passing commuter trains not far from his front doorstep. But as the film progresses, Kurosawa gently destabilizes the space outside the house by fluctuating the relationship between the lights and their sound. At a crucial moment when Sasaki has just forbidden his older son to run off and join the military, the lights of the train race by the living room window, but their sound only follows afterwards, like distant thunder after a flash of lightening. The level of synchronization between thunder and lightening is a key indicator of a storm’s distance from your listening position, and Kurosawa’s slight separation of the two here suggest the son’s destination for a distant war in a world far removed from the one just outside the house.

During another key scene Sasaki confronts his son about his illicit piano lessons. At one point the train lights illuminate the living room with their sound fully synchronized. A bit later in the scene the lights return, but this time without any sound at all. Having been primed for the connection between light and sound we wait and wait, wondering if Kurosawa is pushing the delay time even further than before. But the train sound never comes, leaving us to question the real source of the lights outside.

As his wife sends her son off to the military, all sound drops completely out as the train pulls away from the station. Silence like this is very rare, and opens up a space of infinite potential. Either the space has become so closed that the distance of audibility is reduced to zero, or it has become so open that the space is free to become anything. As the auditory extension drops to nothing, the mother is letting go of her son. This act brings her closer to him in the end, while her husband’s attempts to keep him close only serves to push him further away. Kurosawa toys with his control over extension, and this is fundamentally connected to the narrative theme of distance: these characters are in the process of pulling apart from forces outside of their domestic sphere.

Kurosawa’s approach to the control of audiovisual extension suggests intangible forces at work without blowing the door open to the world of the supernatural. This style is perfectly supported by Kazumasa Hashimoto’s mournful score. Featuring a striking mix of mellotron and conventional acoustic instrumentation, this score creates a simultaneous sense of grounding and ethereality that suits the not-quite-supernatural quality of the film’s tone perfectly.

The film concludes with the family regrouping at a recital in which the younger son is participating. The scene begins with parents gathered in a gymnasium to listen to their children play, and is marked by a direct sound approach that emphasizes the indiscriminate acoustic reverberations of the space. Between performances the sounds of chairs squeaking and footsteps on the hard floor are very pronounced. Then, as Sasaki’s boy sits down, all ambient sound drops out to one of Kurosawa’s moments of pure silence. As he begins to play, an ethereal wind picks up and lifts the grand curtains in the background without so much as an audible whisper. Another world literally blows into the room, and the boy unleashes a sublime sonata rendered in a studio quality recording that belies the realities of the space visible on the screen. The infinite possibilities of the outside world crystallize in this moment, and provide the formal counterpoint to the film’s opening sequence. The winds of the outside world started by calling the family out of the domestic sphere, separating them from each other in the process. Now these same winds have blown them back together, reunited around a point of narrative tension: the boy’s desire to play the piano despite their economic difficulties. In another film the approach to sound in this scene might simply be heard as a cheap solution to the problem of representing live musical performance on the screen: dub in a clean recording of the performance to make up for the poor acoustic realities of location recording. But here Kurosawa uses this technique as the culmination of a very calculated and deliberate exploration of audiovisual extension throughout the film. The relationship between mise-en-scène and sound has been designed to culminate in this moment, and it works perfectly. Tokyo Sonata clearly marks a new level of maturity in Kurosawa’s work. Though I have loved his films up to this point, I now expect even greater things to come.

Tokyo Sonata turned out to be part of an unofficial celebration of city films at this year’s festival, with many titles positing urban space as one of the main characters in their narratives. As counterweight to Kurosawa’s Tokyo as site of social degeneration, Tokyo Marble Chocolate from Japan’s famed IG studios offered a wonderful anime homage to the city. Though you might not expect it from a cartoon featuring a mini-donkey bent on disrupting a young couple’s budding romance, Tokyo Marble Chocolate quietly tackles the problem of representing what has come to be known as an unrepresentable city. Famous for its unfathomable density and general lack of holistic coherence, Tokyo is here rendered almost quaint with a focus on parks and cafes in which the bulk of the action takes place. What is most striking is that the city takes on an air of definitive manageability through the grounding effect of Tokyo Tower, the central point around which the story of two social misfits trying to find love revolves. Frequently visible in the background, the film maintains a consistent orientation with respect to the tower throughout. Because of the tower’s importance to the development of the plot, its omnipresence serves as a spatial device that drives the narrative forward while creating a sense of core for a city so often described as being without center. And so Tokyo becomes a place where people might find love and companionship within the context of urban sprawl, rather than a bewildering environment that fosters a fragmentation of experience and attendant deterioration of social relationships.

New York City was also featured prominently at this year’s festival. I first encountered it in Nicolas Provost’s short film Plot Point: a methodical study of street-level security on the island of Manhattan. First we see shots of police officers and security guards at various points around the city. As these shots unfold, the film builds increasing tension through editing strategies that highlight facial expressions and radio transmissions that suggest a major event brewing. What first seem to be fragmented views of different parts of the city become increasingly unified through dubbing strategies that suggest increasing communication between the various precincts represented. The result is a slow boil on the streets of NYC that culminates in an epic parade of police vehicles streaming out of the central station towards a catastrophe that remains unspoken – but one that 21st Century New Yorkers can sadly imagine all to well. As such, the film develops a portrait of the intensity of police presence on the streets of New York City as part of the daily routine of life on the island.

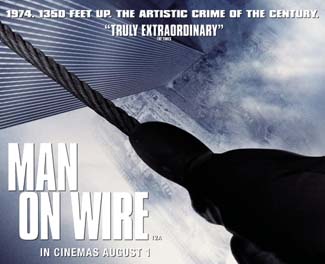

Of course the highest profile representation of New York City at the festival was James Marsh’s highly anticipated Man on Wire, the story of tightrope walker Philippe Petit’s adventure on a thin cable between the twin towers of the World Trade Center in 1974. The film went on to win the 2008 Oscar for Best Documentary, and with good reason. You will not find a more dramatic or entertaining documentary film anywhere; I guarantee it. Just what Hollywood loves most! But there is more to this film than just entertaining drama: it is an homage to the human spirit, and to a city forever changed. Without even a hint of talk about the events of Sept. 11th 2001, Man on Wire is an elegy to the fallen towers – ironically by way of a story about their first major security breach. Made long after the towers were gone, the film deftly mixes interviews with archival footage and newly shot recreations. There is an abundance of footage available of the towers under construction, as well as of Petit’s earlier wirewalking escapades and his back yard preparations for the WTC adventure. In the first half of the film Marsh brings this parallel material together wonderfully to paint simultaneous portraits of the building of the towers and of Petit’s dream to walk between them.

However, despite the amount of film material the filmmakers had access to, the extreme nature of the WTC stunt ensured that there were no spare hands to document the proceedings as they unfolded. So Marsh relies on incredibly passionate interviews with Petit and his cohorts to set the tone of the film, and these interviews are supported by a wonderful series of re-creation scenes boasting fantastic set designs and cinematography that call forth the ghost of the towers from the inside out.

Always highly stylized, these re-creations begin during the film’s opening moments with shots of actors portraying Petit and his crew driving around the streets of Lower Manhattan on their way to the World Trade Center.

The tension builds as the team encounters a series of obstacles on the top floor of the towers before they can reach the rooftops.

The re-enactment scenes then move into a decidedly expressionistic realm once the team makes it up onto the roofs in the dead of night, facing their most difficult challenges as dawn draws ever nearer.

Through the stylized and evolving aesthetics of these re-creations, the film maintains a clear distinction between archival material and dramatization. This distinction works well to evoke the subjective intensity of the events, and to comment on the (perhaps) questionable veracity of Petit’s memory of this emotionally charged journey. Petit and his friends are in tears by the end of the film as they recount the climactic nature of the event, the peak of a group bond that inevitably dissolved after the once-in-a-lifetime stunt was done.

Despite the cinematic skill Marsh demonstrates through his stylish re-enactment scenes, he decided NOT to stage any material for the walk itself. As Petit is about to step out onto the wire, Marsh gives us one simulated POV shot peering over the edge of one tower with a wire extending to the second.

And then the film pulls back, making a dramatic shift in tone from its expressionistic heights. We watch the walk unfold through a series of still photographs set to the sullen solo piano of Erik Satie, a major break from the pulsating Michael Nyman cues and “heist music” by J. Ralph that have driven the bulk of the film.

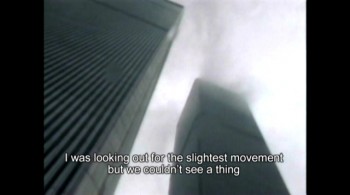

Once in a while we cut to shots from a movie camera on the street below, but all it captures is the air of mystery caught up in the mist gathered at the peak of the towers.

For a film with such a major emphasis on archival footage and dramatic re-enactments, the climax of the film demonstrates remarkable restraint on the part of its director, and makes for an absolutely sublime finish to a riotous tale. In its own way, the film manages to comment on the status of the towers as symbols of the nation by telling the story of a foreigner who conquered them 25 years prior to 2001. At the same time, the film offers a glimpse into the heart of an artist who broke the law to give the world some joy. Amazingly, the authorities respected Petit’s walk as art and he was not charged. Instead they gave him a permanent pass to the WTC observation deck! If he tried this today Petit would be in solitary confinement somewhere on the Cuban coast, the US would be on amber alert, and the CIA would be listening a bit more closely to their French wiretaps. Without breathing a word about world politics, James Marsh has created a film that is as much about the changed nature of the world after Sept. 11th 2001 as it is about the indomitable spirit of an exuberant French acrobat. And all in a format that is accessible enough to garner the director an Academy Award. Rarely do so many strands come together so wonderfully. My hat is off to James Marsh.

Man on Wire was doubly exciting for me because my love of city films is matched by my love of found footage filmmaking. Marsh’s film could easily have been nominated by the Academy alongside Milk for a Best Picture Editing award – if only documentary films were eligible in this category. I’m sad that Milk didn’t win; my favourite part of the film was its loving approach to the combination of archival footage and fictionalized re-creations to capture the spirit of San Francisco’s Castro district in the 1970s. Happily, the long-standing trend of exploring city spaces through the use of archival material seems to be holding strong, with two other festival entries following in the same vein: Luc Bourdon’s La Memoire des Anges sets its sights on our very own Montreal of the 1960s through an eclectic array of archival material, while Terence Davies tackles the Liverpool of his childhood in Of Time and the City. While I missed both of these films during the festival, I had a chance to catch up with the Davies venture upon its Montreal run a few months later.

Like New York City, Liverpool has changed a great deal over the decades. Of Time and the City begins with a shot of a curtained screen rising from the floor of a grand old movie palace. We listen as Davies begins his narration with an A.E. Houseman poem from his 1896 publication of A Shropshire Lad:

INTO my heart on air that kills

From yon far country blows:

What are those blue remembered hills,

What spires, what farms are those?

That is the land of lost content,

I see it shining plain,

The happy highways where I went

And cannot come again.

Then the curtains open, and archival footage of a distant Liverpool fills the screen. Over the course of the film Davies mixes images of Liverpool both old and new, reflecting on his memories while trying to deal with the reality of the changing times. “Home is where one starts,” Davies muses. “But where, oh where are you, the Liverpool I knew and loved? Where have you gone without me? And now I’m an alien in my own land.” But the question is this: does Davies see this alienation as a bad thing? Or is there some good in change that defies nostalgia?

Though there is nostalgia to be found here, Davies’ tone makes it clear that the past he recounts is not an idyllic crystallization of a past that he’d like to hold on to. No, his love for Liverpool is bitter sweet, and his story a genuine coming of age rather than a celebration of golden years gone past. He remembers the days “when football, like life, was still played in black and white…and sports men and women knew how to lose with grace and never to punch the air in victory.” Yet for the people watching this more dignified form of football, life was a product of the “British genius for creating the dismal.” The film dwells on footage of run down housing projects and dilapidated neighborhoods, a situation that Davies places in stark contrast to the luxuries of Church and Royalty. One long montage sequence depicts the residential neighborhoods of the lower class as children play amidst dilapidated surroundings in the shadow of the Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King.

Situated near Lime Street Station, the Cathedral sits at one end of Hope Street facing the Cathedral Church of Christ at Hope’s other end. Boxed in by the Christians, Davies recollects: “I had lived my spiritual and religious life under Popes Pious the XII, John the XXIII, and clitoris the umpteenth, which is enough to turn anyone pagan. As far as I knew, Holy Mother Church still wanted me. But I no longer wanted her, for I was now a very happy, very contented born again atheist. Thank God.” This tongue in cheek tone rules the day throughout Davies’ narration. The Liverpool of his upbringing was rife with contradiction, where the Church presided over poverty while flaunting its excess. Not to mention the trouble they caused for young homosexuals like Davies himself, who recounts his days spent weeping in the pews for some respite from the anti-gay laws of both God and country. In these pews he lost his “girlhood,” and redirected his faith in God to the silver screen – and the wrestling ring. And so he wonders if the recent trend of converting churches into chic restaurants might not be for the best.

Not hailing from Liverpool myself, I found Of Time and the City to be somewhat impenetrable. Davies’ thick commentary is so full of references that perhaps only someone of his age and upbringing might be able to process it all. Nevertheless, the film offers a truly remarkable collection of archival material, bound together through skillful montage, challenging musical accompaniment, and a ceaselessly witty – if pretentious – narration.

Other notable found footage entries included Belgian filmmaker Nicolas Provost’s Gravity exploring Hollywood kissing scenes through a new lens; and Fontage, a nice entry from Mike Hoolboom and Fred Pilon continuing in Hoolboom’s tradition of processing his identity through hand-processed film stock. But the highlight for lovers of found footage was this year’s Bruce Connor retrospective. The program featured 11 films by the acclaimed avant-garde filmmaker known best for his repurposing of appropriated material as epitomized by A Movie and Report. Indeed, seeing these canonical films as they were meant to be seen was a rare treat – the flicker effect in Report really doesn’t cut it on my bootleg VHS. Yet as impressive as his found footage work is, the most interesting parts of the Connor programme were his later films. Looking for Mushrooms and Easter Morning are both relatively recent re-workings of material Connor shot himself in the 60s, and both are structured as series of still images passing quickly enough to suggest movement without succumbing to the illusion of motion that begins somewhere around 16 frames per second. Both set to the music of Terry Riley, these films gesture in a psychedelic direction fostered by Connor’s interest in Peyote at the time the images were captured. Easter Monday, finished just before he died this year, is a probing journey through an unrecognizable San Francisco consisting of abstracted bits of garden flowers and other corners of experience ordinarily neglected by the average passers-by. With their careful attention to the relationships between the formal qualities of all the fragments brought together, Mushrooms and Monday demonstrate how Connor’s understanding of montage – demonstrated so wonderfully in his found footage films – can be applied to more personal material seeking to craft an experience of interiority rather than restructuring the world as projected through the media. Though Connor’s San Francisco likely won’t end up in any tourist videos for its lack of recognizable landmarks, it was a very special take on the city film format.

My pick of the festival this year, however, leaves the city and its found footage representations far, far behind. I cannot overstate the level of my anticipation for Philippe Grandrieux’s Un Lac. His previous films Sombre and La Vie Nouvelle both played this festival in the past and are among the strongest cinematic works of the past decade. Grandrieux has developed an aesthetic that is more genuine and visceral than can be said of most filmmakers, and the experience of his films leaves me breathless every time. But I will admit to having some difficulty with the level of corporeal violence enacted between the characters in his first two outings. And so I have come to wonder how closely his amazing cinematography, montage, and sound design are connected to his penchant for disturbing content. So my big question for the new film was this: can Grandrieux maintain his visceral intensity without having characters come into physical conflict with one another?

My first viewing of Un Lac was thus charged with a bit of anxiety. Set in the rugged winter terrain of Lapland, the film’s first hour slowly introduces us to a family of five –plus one mysterious stranger who threatens to disrupt their tight familial bond. We start by watching a young man, Alexey, as he chops wood for the family fire. Grandrieux frames a close-up on the axe blows repeating with incredible vigour and agitation, the sound of each contact being more felt than heard. Then Alexey falls victim to an epileptic seizure; the camera takes on his uncontrollable shaking, abstracting the already misty environment to an impressionistic palate closer to Brakhage’s Anticipation of the Night than the crystal clarity BBC’s Planet Earth.

So the film begins with a violent charge that could easily set us up for more of what I’ve come to expect from Grandrieux’s previous work. And with the introduction of each new character comes a tremendous potential for violent outbursts, especially when the stranger Jurgen arrives and sets his eyes on Alexey’s sister Hege.

Or when their father Christian returns home from a voyage to find the stranger in their midst.

Is the Jurgen going to hurt Hege? Is Christian going to hurt Jurgen? Is Alexey going to hurt his sister or the stranger? Even without the violence of Grandrieux’s previous work as a primer, the charged nature of this film’s aesthetic makes the potential for violence a tangible reality. Yet instead of developing this tension towards the climax of physical conflict, Grandrieux reveals a family dealing with the stark brutality of their environment by showing each other a remarkable level of gentleness. Some have even described the physical expressions of caring that Alexey and his sister show each other as incestuously inappropriate. But I don’t buy that reading, and prefer to think of their love for each other – and Alexey’s trouble dealing with the stranger’s arrival – as a sign of their close familial bond, keeping them sane in the remote wilderness.

In fact, much of the film operates like an intimate case study of the physicality of human tenderness. Though we spend a lot of time inside the family’s tiny house, we are given no real sense of how this space is laid out or even what it looks like. Within this veritable absence of interior mise-en-scène, Grandrieux concentrates on his characters as they move slowly around their domicile in shallow focus. He emphasizes details of an eye, a hand, a pair of lips, as characters, converse, hold and caress each other in the dark. And the sound design for these scenes is absolutely incredible in its attention to the minutiae of the environment: the stranger’s breath as he sleeps under Alexey’s suspicious gaze; the creaking of the floorboards under inaudible footfalls; and whispers of longing that keep the exterior’s howling wind at bay.

During the Q+A Grandrieux was asked why the new film abdicates his previous commitment to corporeal violence. He answered that the violence is still there, that he’s simply showing a different side of it – here embodied by the film’s setting. The relationship between setting and subject matter is important in the director’s work, for there is a movement outward from the urban environments of the first two films to the wilderness of the third. Un Lac is devoid of the city contexts that allowed for his signature use of incredible outbursts of nightclub sound that fostered the festering misogyny at work in Sombre and La Vie Nouvelle. In the new film the forests of Lapland provide a comparative subtlety that renders the simple act of chopping wood into an experience equally moving in its intensity as anything the director has achieved in the past.

The setting, combined with Grandrieux’s very particular approach to montage, camera movement and sound, ensure an intensely violent physical landscape even in the absence of person to person assault. The real violence inherent to all three films lies in this aesthetic viscerality, and in all three this agitation leads to a kind of transcendence; after a while, you start to see through the density of motion to something beyond. I suspect that his characters in the first two films often feel the same way, as though their physical attacks on each other force open doorways to another world. In Un Lac the harshness of the environment, and Alexey’s epilepsy, offer gateways to the same world. There is an extreme violence to the way a seizure looks from someone on the outside, and yet reports from those who suffer these seizures confirm that they are not in pain and are quite relaxed, often experiencing visions and altered states of consciousness. Alexey’s malady thus seems to be the perfect vehicle for the filmmaker’s signature interest in agitated motion, a character whose exterior violence is part of an interior transcendence.

In the end this is a film about Alexey’s need to transcend the impossibly close bond he shares with his sister, to be able to let her go without anger or jealousy. There is an amazing moment near the end of the film that encapsulates this theme. One night Jurgen and Hege make love, her first sexual experience and one that seems to confirm her destiny to remain with the stranger. The following day, Hege sings for her brother while out on the land. The environmental sound drops away as the melody flows from her lips, an identical strategy to the one used by Kurosawa for the recital at the end of Tokyo Sonata. Out of nowhere, a piano emerges on the soundtrack to accompany her, a dramatic break from the rest of the film’s heavily nuanced treatment of environmental sound and stark absence of musical score. Hearing her sing, Alexey tells Hege that her voice has changed, that it is different now. This is the moment that he realizes he has to give her away, the point around which the whole film revolves. This is the substance of the struggle between the characters in Un Lac; but instead of manifesting itself through acts of physical violence, the film focuses on Alexey’s internal struggle as reflected by the exterior environment. After much anguish, Alexey comes to terms with the genuine quality of the stranger’s affection for Hege, a feeling that Alexey knows all too well. And the film ends with Hege and Jurgen setting off across the lake of the film’s title, the family now divided for the first time.

As with Kurosawa’s new film, Grandrieux’s latest demonstrates that the filmmaker can change his setting and narrative content while keeping his signature tone in tact. So if you found the breast roping and forced coiffure of his first two films difficult, here you can breathe a sigh of relief without worrying that Grandrieux has lost his edge. This is my favourite of his three fiction films, and points towards nothing but greatness for whatever Grandrieux might do next.

Sadly, it seems that whatever Grandrieux brings to future incarnations of FNC, we’ll no longer have the luxury of watching his work unfold across the finest screen in Montreal. Ex-Centris, the media complex that has housed the festival for the past 10 years, has shut down its cinema operations. While they’re keeping the small room open for Cinema Parallel screenings, nothing in the city can compare to Salle Cassavetes, the flagship screening room where so many of the festival’s gems have appeared. Citing the need to use their high-end facilities for bigger and better things, Ex-Centris management announced the closure of the theatre in March of 2009. I have no idea what this means for the future of FNC, but without Salle Cassavetes the festival really won’t be the same. One of the mandates of this festival was to present film of the caliber of Un Lac matched by the highest quality of projection and sound. I recently attended a screening of Un Lac at Mexico City’s Cineteca Nacional and was terribly disappointed, a cold reminder of how material as technically demanding as that of Grandrieux cannot be properly experienced on anything but the finest equipment. I fear for the future of FNC without the Ex-Centris facilities that have gone hand in hand with the festival for so long. So I’m holding onto my memory of those October screenings extra tightly, for these may have been the last time that top-tier cinema will meet first class facilities in Montreal. And that’s a damn shame.