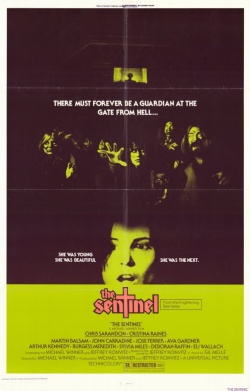

The Sentinel (1977 ): Hell on the 5th Floor

The Sentinel is a supernatural horror film from 1977 that was produced by Universal studios to profit from the recent successes of films such as The Exorcist, Amityville Horror, and The Omen. For Michael Winner, better known for crime films (Death Wish, Death Wish 2, Death Wish 3, The Mechanic, Scorpio, The Big Sleep), The Sentinel was the first and only horror film he directed. I can not remember for sure whether I saw The Sentinel during its initial theatrical run, but I most recently I saw The Sentinel on 16mm at a local Film Society in Montreal (run by local impresario and filmmaker Phillippe Spurrell). Although most people assume The Sentinel was trying to jump on the post-Exorcist demon wave, it is actually more Rosemary’s Baby meets The Freaks, than the contemporary films that immediately influenced it. This is most evident in the ending where, a la Rosemary’s Baby, all the tenants at an apartment building converge on the central female protagonist as hell’s gate opens to unleash a group of (mainly real) physically deformed people.

The film can be referred to as the “Godfather” of horror films, not for its aesthetic merit, but for the way it features a cast of essentially unknown actors who would go on to successful Hollywood careers. The Godfather featured the following then relatively unknown actors who would go on to stardom (or near stardom): Al Pacino, James Caan, Robert Duvall, Diane Keaton, Talia Shire, and John Cazale. The relatively new actors who would go on to successful careers in The Sentinel include: Chris Sarandon as the male lead Michael Lerman; Deborah Raffin as Jennifer; Christopher Walken as Detective Rizzo; Law & Orders’ Jerry Orbach as Michael Dayton; and Beverley D’Angelo as lesbian Sandra. The Sentinel went one further than The Godfather by blending alongside the up and comers a rich cast of has-beens: Arthur Kennedy as the ‘good’ priest Monsignor Franchino who eventually, and very nearly, saves the day; Jose Ferrer as another priest seen briefly in the opening Northern Italy prologue (referencing the Northern Iraq opening of The Exorcist?); Ava Gardner as the real estate agent Miss Logan; Martin Balsam (in a step down from Hitchcock and Psycho) as the absent-minded Latin professor Ruzinsky, who helps decode the Latin phrase that priests Kennedy and Ferrer recite in the opening; Eli Wallach as police detective Gatz with a grudge against a lawyer (played by Chris Sarandon), who’s previous wife and girlfriend committed suicide; John Carradine as Friar Francis Matthew Halliran in his umpteenth horror film; Sylvia Miles in the juicy role as one-half of a lesbian couple, Gerde Engstrom; and, last but not least, Burgess Meredith as Charles Chazen, cast against type as the proverbial eccentric old man who ends up being the malicious evil figure of the piece.

Cristina Raines

The film’s lead is the attractive Cristina Raines as a model/actress Alison Parker and, in the John Cassavetes Rosemary’s Baby role (Guy Woodhouse), Chris Sarandon as her lawyer boyfriend Michael Lerman. Raines is passable, as a Susan Dey look-alike (from the popular 1970s TV show “The Partridge Family”). Strangely enough, Cristina Raines would next star alongside Harvey Keitel and Keith Carradine in Ridley Scott’s The Duellists (1978), but would then feature almost exclusively on television (albiet quite successfully). Deborah Raffin co-stars as Parker’s best friend Jennifer. For feminists who point to today’s media as manipulators of the anorexic female body, look no further than Raffin and Raines, who look like walking carrots with withdrawn, skeletal faces. A large part of the fun of watching The Sentinel today comes in picking out all the soon-to-be stars in bit roles: Jeff Goldblum (Jack) appears as a fashion photographer; Christopher Walken appears as Wallach’s taciturn sidekick Detective Rizzo; Beverly D’Angelo as Sandra, the younger, mute half of the lesbian couple; ??Law and Order??’s Jerry Orbach has a small role as an advertising director; Tom Berenger comes into the fray as the boyfriend in the final scene which repeats the earlier scene of Gardner showing the apartment to prospective tenants/sentinels –a scene which introduces the circularity and open ending so dominant in late 1970’s horror– and Richard Dreyfuss can be spotted as the “man on sidewalk talking to girl in red sweater.”

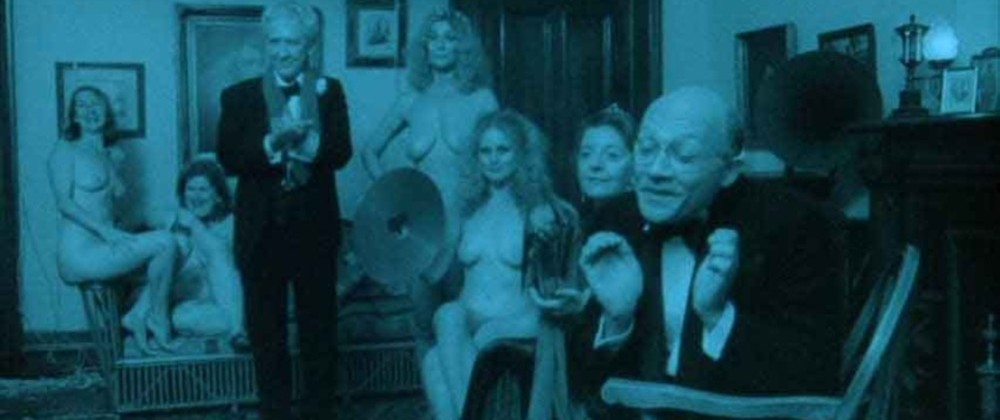

In most horror films you would think the source of any demonic portal would be the basement (as in the similar styled film from 1978, The Evil, or Fulci’s 1980 The Beyond), but in The Sentinel the ‘gates to hell’ are situated in a fifth floor apartment that appears inhabited, except for the presence of horror mega-veteran John Carradine, an old blind priest who spends his days sitting looking out of the apartment’s fifth floor window. (And as Parker quite rightly asks Miss Logan, “If he is blind, what is he looking at?!”) We learn that Carradine is in fact the last in the long line of sentinels whose duty it is to protect the gate of hell, with Alison Parker (Raines) being groomed as his successor. We know things will not end well when newcomer Parker’s introduction to the tenement is a brash lesbian exhibitionist display by Sandra, in what is the film’s best (or worse, depending on your taste?), and certainly most audacious, moment: she masturbates in plain view of Alison, who has come down to introduce herself as a new neighbor!

It’s little wonder this notorious scene is rarely mentioned by queer film theorists, since it is hardly ‘progressive’. Sure it must be liberating for a gay person to see representation, but these two characters are so over-the-top that they don’t represent anything verging on ‘real’ people. And of course it is precisely this non-realist behaviour which makes the scene such a show-stopper. For starters the two are an odd couple, with Sylvia Miles 45 years old and Beverly D’Angelo 26 years old at the time of the film’s release. Miles in a faux Swedish/German accent (her character is Gerde Engstrom) and Sandra waltz into the living room wearing, respectively, a black one-piece swimsuit (Gerde) and red leotards (Sandra). Gerde goes for coffee. Sandra remains mute during the whole scene, staring lasciviously at Alison, who is seems uncomfortable from the get go. The next moment is the one that breaks any pretence of decorum, and signals to the viewer that the gloves are off and we are entering into absurdity. Two shots and one edit signal the rupture and hurdles the viewer into major comedy of embarrassment mode (before it became a common comic foil). The camera aims its lens at a medium close of Gerde’s left hand as it moves along from Sandra’ right knee to her inner thigh. A quick cut to a medium shot of Alison as she quickly spins her head away from the offending sight. From this point on anything goes, and practically does. Gerde leaves the room to answer the phone and then we get a series of shot counter-shots from Sandra squirming as she furiously rubs her loins and Alison squirming (for other reasons) in her seat. Alison, still trying to pretend as if she doesn’t notice, politely coughs and turns her head away again. Sandra achieves orgasm, while Alison stares incredulously. Gerde returns and sits next to Sandra and the following dialogue ensues:

Gerde: “We’re proud of our apartment. It took us a long time to furnish it properly.

Alison: “What do you do for a living?

Gerde: “We fondle each other.”

Alison takes this as her cue to leave, and the conversation continues outside the apartment in the hallway.

Gerde: “It’s rude to eat and run.”

Alison: I didn’t eat, I drank.”

(For an hilarious mash-up of this scene re-scored as a faux television sitcom called “The Dykes Downstairs” click here.)

She is then invited to Chazen’s birthday party for his cat Jezebel (who we later see gleefully eating the bird, a parakeet named Mortimer, seen earlier on Chazen’s shoulder!). Not only are these people odd, they are all dead. Only Alison seems to be able to see them, and has the ability, or the curse, to see things other people do not. One of the film’s most effectively moody centerpieces concerns Parker investigating nighttime noises coming from the above floor, and encountering some of these demon inhabitants, including her own deceased father. In one of the film’s most gruesome moments, she attacks her dead father with a knife and cuts off his nose. In the film’s climax two opposing forces vie for Alison: the demonists, led by Chazen, who want to open the gates of hell; and the priests who want to keep it shut and successfully replace Carradine with Alison as the new sentinel.

But one must wonder about the Christian values of this priesthood, if the Sentinel must commit suicide to become the next guardian. In the final shot of the film we see Parker sitting at the window of a newer apartment complex, with the real estate agent Miss Logan bringing along a new prospective couple. Is this the new house guarding the gates of hell? If so, and if Parker is the new sentinel, why would Miss Logan be attempting to recruit a new sentinel?

What stops the film from scaling the heights of great 1970s horror films, along with the byzantine treatment of the film’s implicit theological questions, is director Michael Winner’s pedestrian style, exemplified by his over-use of the zoom lens (like the frequent zooming in to Carradine at the window). When properly used, like by Mario Bava, Jesus Franco, or Stanley Kubrick in The Shining, the zoom lens can be a great tool in a horror director’s arsenal. But the zoom in Winner’s hands has no pizzazz or sense of thematic resonance. It merely replaces the costlier, more time consuming tracking shot, of which there are only a few, and none attaining the type of objective or authorial assertiveness associated with the uncanny or the supernatural. When Winner wants to suggest something askew he lazily shifts to a wide angle lens, but again, the ultimate result is a foregrounding of the technical rather than heightening of any emotional fear. And yet the climax has a few moments of frisson, like the shot of the physically deformed face that crawls into close-up view at the bottom of the steps surprising us and Parker (the overall effect is similar to the new spider walk scene in The Exorcist, where the blood-filled mouth of Regan comes spurting forth blood right up to the camera lens). More physically deformed people come crawling out of the woodwork to stalk Parker. Her dead father and his two overweight, grotesque prostitute playmates appear sitting naked on the landing. The nude Sandra and Gert Engstrom cannibalize a victim. Parker’s boyfriend Lerman reveals himself as one of the ‘undead.’ Chazen hands her a knife and tries to seduce her to attempt suicide. Monsignor Franchino and father Halliran, brandishing a Van Helsing-style cross, interrupt to save the day. But is their agenda completely honest when it includes the conclusion of the sentinel circle?

John Carradine

The cumulative effect of the climactic scene is one that unsettles for varying reasons. First because the orgy of the ugly and physically deformed takes us completely by surprise. But it is equally unsettling because most of the physical deformities are real and not a product of special effects wizardry (some are the work of make-up genius Dick Smith, who of course also worked on The Exorcist). What takes away from the horrific effect is knowing that many of these ‘evil’ representatives are real ‘freaks.’ Unlike in Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932), where the ‘real’ circus freaks become are strong, central characters with human emotions and feelings, Winner introduces them simply for their shock value. Using their physical deformities (oversized lips, face, etc.) to symbolize the evil of hell is exploitative to say the least. Clearly, The Sentinel is a product of its age, and such audaciousness –for better or for worse– would never fly in today’s more politically sensitive atmosphere, at least not by a major studio such as Universal (click for original trailer). These flaws aside, The Sentinel is remembered fondly by fans who compare its slow-burn style favorably to the faster-paced horror films of today, and it has slowly earned its keep as a minor cult horror classic. If nothing else, it contains one of the most jaw-dropping scenes, of a non-violent variety, in a horror film –Beverly D’Angelo’s in-your-face masturbatory come-on to a very uncomfortable Alison Parker.