The House of Sand

Western Brazilian Style

From the opening wide shot of other-worldly sand dunes, not unlike the uncanny Alaskan landscape in Christopher Nolan’s Insomnia, The House of Sand (Andrucha Waddington, Brazil, 2005) resembles a meditative science-fiction film. The actress, Fernanda Torres, apparently likened it to Kubrick’s 2001; the sand could be a metaphor for the nothingness of space, and the lingering shots of desultory images may suggest temporal rifts. Amid the generous use of extreme long shots on the minimalist backdrop of the Northern Brazilian desert along with the appearance of doubles, time lapses and motifs on astrophysics and relativity, the evocation of genre is justified. However, also noteworthy is the film’s affinity to another genre: the western. Its iconic imagery of civilized folk seeking opportunity and persisting in the unforgiving wilderness represent a quintessential western theme. Seen as an allegory about the founding of a nation –photographed on or near the Lencois Maranhenses National Park in Maranhao– The House of Sand is thematically a Brazilian western.

As Stephen Prince contends, the western film exhibits the following recurring themes:

1) the tension between civilization and the wilderness,

2) the man of violence, and

3) the mythology of a lawless, incipient nation.

Tension Between Civilization and the Wilderness

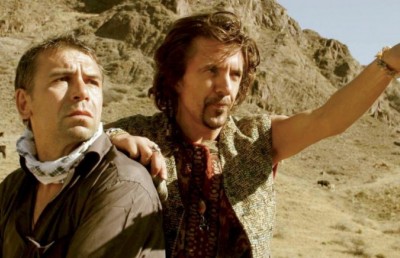

The first theme is introduced in the exposition through the long shot of diminished human figures traversing great sand dunes. Visually, the landscape dominates the frame relative to the dwarfed movements of a caravan, thereby creating a general anxiety for those who appear to be trekking into oblivion. When Vasco (Ruy Guerra) identifies his forsaken lagoon, the preposterous barrenness of his real estate spells his doom. In later scenes, the settlements in the sand resemble homesteads in the West erected in defiance against the elements and other less palpable dangers, like isolation. Waddington’s long shots are informed by Fordian landscape cinematography as seen in Hollywood westerns of the 40s and 50s; the homesteads in Monument Valley and the individuals around them are mere specks within the panoramic canvas of resonant canyons and open ranges. The early scenes in The House of Sand imply that in this oppressive desert the two likely outcomes for settlers are either a hasty exit or a life-long struggle with the elements. The women who stayed behind would remain for several lifetimes.

Aurea (Fernanda Torres) reveals herself as a woman of the city at the turn of the 20th century; she repines her beloved piano and the refined sounds of classical music. Upon arrival at Vasco’s lagoon, Aurea rejects the empty promise of a home in the sand and attempts to abandon the harsh, seemingly uninhabitable environment. Despite the subtle but palpable sexual tension between her and Massu (Seu Jorge) –a black settler she befriends– in the early years of their acquaintance, the strain between her cultured upbringing and the sand (and those of the sand) persists. Even after the consummation of their love 10 years later, that tension is transposed to Maria, her daughter. Maria’s return to her mother’s house in the final sequence is also relevant to this tension because the elderly Aurea has adapted to the wilderness; if the two remain together, either in the city or the sand, the tension between civilization and the wilderness will continue to play out. The women are locked in this fateful cycle because they have embraced the opposing forces of civilization and the sand, respectively.

The Man of Violence

In a classical-style western like George Stevens’s Shane, the protagonist is a man of violence who struggles unsuccessfully to morally rise above his nature in an effort to fit in, or escape a shadowy past. In The House of Sand, similar characteristics are imputed to the lead character, Aurea. Her violence is physically indirect, but its intensity is equally formidable. When Vasco is fatally injured at their settlement, Aurea (and her mother) is horrified, but leaves him for dead; as far as intentions go, in the words of Charles Laughton’s Sir Wilfrid Robarts, she executed him. Further, when she finally succumbs to Massu’s unspoken affections in a visually carnal sequence, Aurea again violates her protracted efforts to return to civilization by initiating sexual intercourse with a man of the sand. That moment also marks her acceptance of what the wilderness has to offer, in violation of her previous convictions. In these two instances, Aurea’s humanity is depicted in the same veins as those in well-established myths of the West. Armed with something other than the gun, she represents a passively aggressive woman of violence who is as deadly as her male counterparts.

The Mythology of a Lawless, Incipient Nation

The House of Sand adopts another western theme in its story of Brazil, the country of Portuguese colonial heritage and black slaves. Of particular interest is the formative period of lawlessness that affects an unfledged society, like those depicted in fictions of the old West. In the westerns of Ford and Hawks (and even the recent Open Range directed by Kevin Costner), the male protagonists are outsiders whose use of violence, though morally justified, matches or exceeds those employed by the bad guys. The tense meetings between Vasco and the intimidating posse of black settlers point in the direction of a stand-off or shoot-out, but it is Aurea’s character who follows through. After resisting her new frontier for a decade, she finally reconciles with her fate and joins the society of an unfamiliar race. Put simply, Aurea’s family saga goes from violence as central to survival, to harmonious assimilation with “the natives,” and by inference the eventual formation of a cohesive multi-racial nation. In the words of the director, “the union of Aurea and Massu tells a little bit about the next step in the Brazilian society.” [1]

Glauber Rocha & Science Fiction

A respectable discussion of Brazilian films, whether overtly political or genre-based, requires some context from their predecessors. In a correspondence with Donato Totaro on the Brazilian western, Glauber Rocha’s Antonio Das Mortes came up. Antonio, winner of Best Director at the 1969 Cannes Film Festival has been misconstrued as a South American political film, according to the late Glauber Rocha. Rocha asserts that Antonio is a socio-political examination of an archetypal Brazilian character, personified by the protagonist, and mystical beliefs predominant in the Northeast. The former bears close resemblance with Aurea’s character in The House of Sand. In an interview published in 1970, Rocha states generally that in the revolutionary history of Latin America –a context for the narrative of ??Antonio??– “the provocation to violence, the contact with everyday bitter reality that may eventually produce violent change… come only from individual people who have suffered themselves and who have realized that a need for change is present.” [2] Aurea and Massu’s union seems to represent such a revolution. More importantly, dramatic character transformation and the choice of violence in basic survival found in both Antonio and Aurea are similar; Rocha says, “Antonio, in my film, reverses his own past, he goes against the man he once was, against the class which he has served in the past, to create his own future.” [3] Therefore, strong western themes are present and embodied in the protagonists of both films.

What of mysticism? Perhaps the science-fiction-like mood in The House of Sand reflects, with great subtlety, the African spirituality that permeates Brazilian religious culture; Waddington implicitly depicts Massu’s character as a descendent of slaves from Africa. Otherwise, there is no room for any serious consideration of such genre classification here.

In an interview with Elvis Mitchell, first-time science-fiction director Danny Boyle described with frisson that a “slower pace” was necessary in his new space movie Sunshine. Boyle described his fictional world as having “that gathering sense of eternity… an endless place, [a] vacuum.” [4] This concept of the sci-fi genre evokes the work of Andrei Tarkovsky, Stanley Kubrick and Ridley Scott, but it doesn’t match the design of The House of Sand. Though Aurea was confined by seemingly limitless sand and the ocean, the physical space in this film is terrestrial, not infinite, while the depiction of time is not eternal but cyclical. Moreover, despite multiple references to cosmic phenomenon, such as Haley’s Comet and solar eclipses, the prominent feature of this generational drama centers on the human struggle in a formative republic; the intentions of the narrative are more down-to-earth than celestial. Still, one similarity holds for both genres in this film: the exploration of frontiers. But the Brazilian desert is terra not outer space.

Endnotes

1 Michael Guillen. The Evening Class. 25 Apr. 2006.

2 Gordon Hitchens. “The Way to Make a Future: A Conversation with Glauber Rocha.” Film Quarterly, Vol 24. No 1 (Autumn, 1970): 27-30.

3 Ibid.

4 “Danny Boyle.” The Treatment. KCRW. 18 Jul. 2007.