Testimonies to Louis

Loved by all

On June 14, 2012, André Habib, professor at the University of Montréal, Canada, organized a tribute to Louis Goyette at the Claude-Jutra theatre at the Cinémathèque québécoise, that included a specially selected program of experimental films that Louis would regularly teach. The evening included some touching tributes by some of his former colleagues, friends and students. The list of films screened that evening was: Mouvement Perpetual (Claude Jutra, 1949), Castro Street (David Rimmer, 1966), a film that Habib quoted Louis as saying was the film he would most want to see before dying), At Land (Maya Deren, 1944), Fireworks (Kenneth Anger, 1947), Moth Light (Stan Brakhage, 1963), and Self Song, Death Song (Stan Brakhage, 1997). Among the people who spoke eloquently about Louis were Jean-Claude Marineau, Paul Landrieu, André Habib, Annie Hardy and Tom Waugh. The tribute was capped off by a beautifully rendered hommage to Louis by some of his former University of Montreal students, who made a short collage film of black and white rendered images from some of Louis’ favorite films. To honor Louis’ love of cinema, unbeknownst to those in the audience, a 16mm projector was reeled into the back of the theatre, the lights were turned down, the projector started, and we were treated to the comforting sound of the whirring projector and stream of white light overhead illuminating the screen with snippets from Louis’s favorite films. I could not think of a better tribute.

Below I’ve made my own little collage of tributes from some of the people who were touched by Louis:

KATIE GILKESKatie Gilkes is currently the Manager of IITS Cinemas at Concordia University. Prior to this position she has served as Event coordinator and also Projectionist in the same department. Katie has a BFA in Film Production (’04) and an MA in Art Education (’09) from Concordia.

In my first year at Concordia as an Undergraduate student in Film, I encountered Louis. At first, I was a little shocked by his enthusiasm – expecting (in my 18 year old naiveté) the dissemination of experimental films to be a calculated, deeply boring affair. But Louis’ enthusiasm was contagious! He obviously took much joy from teaching film. He would often break out into song or dance and had all of us mesmerized and engaged and even sometimes laughing uncontrollably. I especially remember his spontaneous version of “Evil Woman” by Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) as part of discussion on Kenneth Anger’s experimental film Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome. Through his courses I came to see some of my favourite films for the first time; Variations on A Cellophane Wrapper and Real Italian Pizza by David Rimmer and Valentin de las Sierras by Bruce Baillie. In retrospect, Louis had mastered the perfect balance between serious academic discourse and pure unadulterated fun; he truly opened my mind and my heart to these films and very much inspired me throughout my studies.

Shortly after beginning my degree, I became a projectionist at Concordia and had the double pleasure of being Louis’ student and his projectionist. In the many years we worked together, he never came into the projection booth without a smile or a little joke, even in the midst of a technical disaster! He was so great to work for in fact, that the projectionists would fight over who got to work for him…

I’m now into my twelfth September at Concordia and I have to say that Louis’ smile, his warmth and his enthusiasm are truly missed by all of us. He was a wonderful guy, an inspiring teacher and he will not be forgotten.

Sincerely, Katie Gilkes.

ANDRÉ HABIBAndré Habib is a professor in the Department of Art History and Film Studies at Université de Montréal. He is co-editor for the online film journal Hors champ. Habib has co-edited a book on Chris Marker with Viva Pacci, Chris Marker et l’imprimerie du regard, and his writing has appeared Spirale, Substance, Hors champ, Lignes de fuite, Senses of Cinema, Offscreen, Intermédialités, Cinémas, and Post-scriptum. He has also curated film programmes at the Cinémathèque québécoise for many years.

On Brakhage (for Louis Goyette)

“Those who remain”

“Death is a meaningless word.”

(Stan Brakhage, 2001)

In the middle of writing this essay I learned of the death of my friend and colleague Louis Goyette, who was a part-time professor at The University of Montreal, Concordia University, and the University of Sherbrooke, and who influenced a whole generation of film students. His courses on experimental cinema, film history, Quebec cinema, and many others, left an indelible mark on those who had the pleasure of taking them. The news of his passing –we knew he was sick but all thought he would pull through– simply left us stunned.

Through his generosity, refinement, and energy, Louis cultivated a pure passion for cinema, better than a battery of scholarly essays, conferences, and research. Thanks to him, at the University where I teach, a course like “Experimental Cinema” has become untouchable, bearing Louis’ imprint, to which I hope we will remain faithful, by searching for that spark in the eyes, the spirit and the heart, like only Louis knew how. I urge you all to read this wonderful essay which I asked Louis to write for Hors champ several years ago within the framework of a dossier on Michael Snow. [The original French article is here, the English translation here.] In writing about –among many other things– the filmmaker’s pedagogy Louis demonstrated, as always, his own magnificent pedagogical skills. The present text on Brakhage marked by my own long-standing reflections on the work and persona of Brakhage, is impregnated with memories of this fabulous man who was Louis Goyette, and who we miss already. This essay is naturally dedicated to him. [To read Habib’s essay in its original French, click here.]

ANNIE HARDYAnnie Hardy was a former student and teaching assistant of Louis.

Hommage pour Louis Goyette

J’ai été l’étudiante de Louis Goyette ainsi que son auxiliaire d’enseignement, et comme tous les élèves que je connais qui ont eu cette chance, je l’aimais beaucoup. Le côtoyer à l’université de Montréal m’a amené énormément de bonheur et j’aimerais offrir ce petit témoignage à sa mémoire.

Ma rencontre avec Louis s’est faite dans le cadre de son célèbre cours de cinéma expérimental. Découvrir avec lui Maya Deren, Bruce Baillie, Michael Snow, les films-collages de Bruce Conner et d’Arthur Lipsett, aller avec lui au cœur de l’histoire de l’animation expérimentale, voir avec lui mes premiers Stan Brakhage, c’est une expérience qui ne s’oublie pas. Aussi extraordinaire que les films eux-mêmes était la manière qu’avait Louis de nous en transmettre l’amour à travers les longues discussions qu’il entretenait avec nous après chaque projection. Rendre hommage à ce professeur passionné et généreux, c’est d’abord, je crois, garder en mémoire, et tenter de mettre en pratique, cette manière qu’il avait d’inviter ses élèves à s’approprier les films. C’est garder en mémoire la liberté et l’accueil qu’il mettait au centre de son enseignement. Pour moi, ce cours fut un événement marquant, non seulement parce qu’il a été mon introduction à tout un nouveau champ de possibles en cinéma, mais aussi parce qu’il s’est avéré l’occasion de rencontrer cet homme des plus inspirants.

Quelques années plus tard, j’ai eu la chance de côtoyer Louis de nouveau à titre de correctrice pour ce même cours. Ce fut l’occasion de retrouver ces films et cet enseignement qui m’avaient tant marqués, et aussi de découvrir un peu mieux l’être humain si sympathique derrière la figure du professeur. Je m’ennuierai de son enthousiasme, de cette manière qu’il avait de me faire rire et de m’étonner, de sa bonne humeur contagieuse, et de toutes ces discussions sur le cinéma que nous avions. Je lui suis aussi redevable de nombreux conseils et encouragements, et je le remercie du fond du cœur pour sa bienveillance de professeur dévoué.

Louis était très impliqué avec les œuvres qu’il enseignait et une trace de lui reste pour moi dans chaque film qu’il m’a fait connaître. Je me rappellerai notamment d’une chose qu’il avait dite lors d’une de ses classes, juste avant de présenter Castro Street de Bruce Baillie : si ma mémoire est bonne, ses mots exacts étaient, “si j’avais à choisir un seul film à voir avant de mourir, ce serait Castro Street.” Ces paroles m’ont beaucoup marquée et je m’en suis toujours rappelée. Désormais, elles teinteront l’œuvre de son souvenir chaque fois que je la regarderai.

Merci, cher Louis. Je te salue.

JOHANNE LARUEJohanne Larue is a part-time professor in Film Studies at Concordia University

Louis was an especially generous man and teacher. The testimonies that keep coming in, from 3 universities in Quebec, from friends of the Cinémathèque, from around the globe even and across time, it seems, attest to this : 20 years worth of giving and nurturing and inspiring young cinema students in his own unique style, Louis has left an indelible and imperishable mark.

Tous les étudiants qui l’ont connu vous le diront : Louis avait la vocation. Il faisait bien plus que partager son savoir. Il n’avait pas seulement à cœur de former des érudits. À chacun de ses cours, il inspirait. Il confortait ses étudiants du Bac dans le choix audacieux, un peu fou et sans doute téméraire qu’ils avaient fait en s’inscrivant aux Beaux-Arts, en rêvant de cinéma. Louis les a magnifiquement décillé – en démystifiant certains pans de l’histoire du cinéma, avec adresse et humour; en leur récitant, mimant ou chantant, quand il le fallait, les rouages de l’esthétique du cinéma, la poésie du cinéma expérimental ou la nature même du cinéma québécois, des matières qu’il défendait comme nul autre.

I find myself wandering back to a conversation I had with Louis, years ago, about experimental film. We had both been recently exposed, by John Locke, to Arnulf Rainer, the Peter Kubelka short, and were marvelling at the beauty of the film’s ontological purity : such a minimalist work, a succession of white frames and black frames, optical noise then silence – “this 1960 film should have been the first movie ever shot,” we exclaimed ! And then we were floored by a thought : here was a film, here was the ONLY film, in all of cinema’s history, that one could see with their eyes closed. Because the closed lid becomes a screen unto which the light and absence of light can actually be perceived… Well, can we not entertain the same notion about Louis? Louis’ light has not been extinguished. It is simply that we must now close our eyes to see it.

Merci Louis. Tu resteras toujours avec nous.

DAVID GEORGE MENARDDavid George Menard epitomizes the career of a Polymath, well educated and professionally groomed in the Arts and Sciences. He received his Bachelor and Master of Fine Arts from Concordia University Montreal, his Master of Sciences from University of Tennessee Knoxville and his Bachelor of Arts and Sciences from the University of South Florida Tampa. As a Physicist working in optoelectronics for Lockheed Martin Aerospace, he designed thermal imaging and night vision systems. As a Filmmaker producing art films and high definition videos, he formalized the use of and assisted professor Louise Lamarre in the development of a holo-editorial layering process, which allows filmmakers to composite images digitally in-camera during studio production. Since completing his Master’s degree David returned to completing his unfinished PhD in Physics and has pursued screenwriting, film theory and film production.

A Poem Dedicated to Louis

“Ah! Wild Wilde Wilderness”

Horses, horses, me red face bay,

Today we ride all, all the way.

No time to work, no time to idle.

No bit, no spur, not even a bridle.

Horses, horses, forget ye bible,

Today we ride on no sidesaddle.

What wind breathing horses make!

Ride on brethren, ride on win the race.

Horses, red face horses, no time to piddle,

Today we ride merry to yonder bridal.

What day brings us this splendid space!

Astray we ride merry to stuff our face.

Horses, horses, me red face bay,

Tonight we ride all, all the way.

Long tail, big head, too much bride-ale,

Upside down, inside out, there we lay.

Disgrace not horses winning no race,

Unbridled wining horses warm the hay.

Pray me horse tale maiden in jouissance,

Wild Wilde Wilderness in Louis semblance.

George David Maynard, copyright 2012

NICOLAS REANUDNicolas Renaud has an academic background in Film and Sociology and is co-founder of Hors champ (1996), an online film and media journal affiliated with Offscreen. He has published numerous articles on cinema, art and media, in Hors Champ and in other publications. In conjunction with Hors Champ, Renaud organized special screenings and lectures in collaboration with the Cinemathèque québécoise, including an event with Stan Brakhage in 2001. Renaud instructs camera and Super 8 film workshops at Main Film (an independent film center/co-op in Montreal). Since 1998 he is also a practising artist who has made video installations and short films that have been exhibited in Canada and Europe. Renaud also teaches Film Studies part-time at Concordia University.

I met Louis Goyette for my very first teaching experience. Louis and I taught two sections of a same course, so we had to speak regularly to coordinate the material. Two simple things struck me about him in our first few meetings. First, everything he did around a course was with joy, the joy of teaching, of sharing, of re-discovering a film each time. I can’t see Bande à part again without thinking of him. Second, he made it sound natural that I could bother him about every practical question surrounding the logistics of a course. He made it easy for me and I’m grateful. We repeated the experience with a shared course a few years later. Such fun we had choosing films, designing exams, and discussing many other things…Always spreading his joy and generosity, and students told me how much they appreciated him. Merci Louis.

DONATO TOTARODonato Totaro is a part-time professor or Film Studies at Concordia University and editor of Offscreen.

I knew Louis since the mid 1980s, when we were both undergrad film students at Concordia, and then from the 1990s on as colleagues at the same university (Louis started teaching one year before me, in 1989). Being fluently bilingual Louis had the benefit of also teaching in French, therefore extended his teaching to the University of Montreal and the University of Sherbrooke. You can pull out all the clichés about how Louis “did not have a mean bone in his body,” “how he never had a bad word to say about anyone,” [all true for him] but the one thing that characterized Louis to me was the way he took on everything in life with passion and joy. For example, I remember the day he first saw my relatively newly born son on a chance meeting downtown near our work office. He literally jumped in the air, so happy for me and continually complementing on how adorable and cute my son was. I will miss our annual phone calls at the end of summer to discuss our upcoming courses and talk pedagogy. I will miss our chance meetings around work which would always end up with an impromptu coffee or a (usually long) standing chat to ‘catch up.’ I will miss Louis always graciously putting up with my imperfect French. Most of all, Louis was generous, kind, and loving, and I will miss that. I will miss knowing that Louis’ unbridled joy will no longer cross my path.

THOMAS WAUGHThomas Waugh is a Professor of Film Studies & Interdisciplinary Studies in Sexuality at Concordia University, and holds a Concordia Research Chair in Sexual Representation and Documentary. Waugh’s research publications and teaching on documentary have touched on Quebec direct cinema, the National cinema. His interests in sexual representation span queer film and video, pornography and homoeroticism in moving image media as well photography and graphic art, Canadian and Quebec cinema, and HIV/AIDS. Waugh’s books include the anthologies, Show Us Life: Towards a History and Aesthetics of the Committed Documentary (1984) , Challenge for Change: Activist Documentary at the National Film Board of Canada (with Michael Baker and Ezra Winton, 2010), and The Perils of Pedagogy: The Works of John Greyson (in press, with Brenda Longfellow and Scott MacKenzie, 2013); the collections The Fruit Machine: Twenty Years of Writings on Queer Cinema (2000) and The Right to Play Oneself: Looking back on Documentary Film (2011); the monographs Hard to Imagine: Gay Male Eroticism in Photography and Film from their Beginnings to Stonewall (1996), The Romance of Transgression in Canada: Sexualities, Nations, Moving Images (2006), Montreal Main (2010); and the edited art books Outlines: Underground Gay Graphics From Before Stonewall (2002), Lust Unearthed: Vintage Gay Graphics from the Dubek Collection (with Willie Walker, 2004), Gay Art: A Historic Collection (scholarly edition, with Felix Lance Falkon, 2006), and Comin’ At Ya! The Homoerotic 3-D Photographs of Denny Denfield (with David L. Chapman, 2007). Forthcoming is the monograph Joris Ivens: Essays on the Career of a Radical Documentarist, and his current research interests are an interdisciplinary approach to confessionality. He is also co-editor with Matthew Hays of the series of 21 monographs Queer Film Classics (Arsenal Pulp Press, Vancouver).

To mourn a person as fine as Louis is an experience that is unique and individual for everyone, and this is mine. Profs are not supposed to witness their former students’ passing, except in wartime. But past decades have proliferated this experience that we are not supposed to have. Such turnarounds are part of the movie-like lives we all live.

I was tremendously moved by the special screening event at the Cinémathèque this past June, in the presence of adoring and adored colleagues, students and family. I am grateful to André Habib and his group for the heartfelt eloquence of the homage they designed. It was fascinating to see a slightly different Louis than the one I knew—there are many of them—in particular the one experienced by his colleagues and students at Université de Montréal, and with whom he shared his expertise and his love of experimental cinema. There could have been several tributes, and in fact each time one of Louis’s friends catches a movie where a moment resonates with one of Louis’s ideas or obsessions, that moment will turn into yet another cinematic tribute. My own tribute evening would have been stuffed with the trashy art feature films and the not-so-art and not-so-trashy films that Louis and I loved to see together (usually after fries at La Paryse with his bosom buddy Denis tagging along), and Il était une fois dans l’Est, that-over-the-top 1973 Michel Tremblay melo screamer, my favorite Quebec movie and one of Louis’s, would have pride of place. There might also have been a few clips from selected Oscar award ceremonies that Louis and I had the tradition of shrieking at together year after year.

The priest at the Grand’mère funeral in April offered the humourous reflection that Louis the cinephile would no doubt be receiving an Oscar in heaven, but little he seemed to know… If I spoke that June evening, surrounded by Louis’s blood family, it was to affirm Louis’s other family, his chosen other family, an alternative family of friends and lovers, his belonging to a gay network and community in which both his work and leisure were rooted, as well as many of his personal relationships. This community is also in mourning and must not be passed over in silence in the sphere of public official memorialization. He loved his family and his cinemas, experimental or trashy, but he also adored friendship, intimacy, desire and the flesh, and we his “other” friends, friends of Dorothy also, of Judy, shared his loves and loved him in return. For this reason, I was happy that the choice of experimental filmmakers screened that June evening at least reflected this minority identity and this affirmation of sexual diversity—on screen as well as off screen: Maya Deren, Kenneth Anger and Claude Jutra.

I met Louis when I taught him in the fall of 1986 in my seminar on English Canadian film, and twenty-five years later we were still the best of friends. We had already planned our annual date for the awards evening at the Mel School in May, but Louis suddenly left the building and I went alone. In my 1986 seminar, Louis worked with great enthusiasm on Claude Jutra, and it is not recognized, I believe, that it was Louis who did the last interview with Jutra –a very lucid Jutra by the way– three weeks before his suicide in November of that same year.

I was proud to translate Louis’s essay on Jutra’s English Canadian films for the memorial issue of Cinema Canada, an essay strikingly original, passionate and accomplished for a BFA student. I take the room here to cite a few lines –well more than a few– including a brief citation from the interview with Jutra:

On several occasions, Jutra declared that he “had to express himself in filmmaking whatever the cost,” because it was like a drug, a veritable passion. Directing for the CBC gave him this chance to express himself. His acceptance of several projects in Toronto was due to the fact that nothing interesting was available in Quebec. In my interview with him on October 14 1986, Jutra offered this clarification: “Every Québécois filmmaker who spoke English and who was interested in working in English was welcome to participate in this project. I very often went from one side to the other, that is, carrying out projects at the same time in Quebec and elsewhere. I was doing the Montreal-Toronto shuttle. I took the train to go to Toronto but I would come back regularly to Montreal to work on other projects. People thought that I had been in exile in Toronto for years but that’s false. In Toronto, everything went well. I really like working with the actors I had. As for the films, they were suggested by the CBC people. They came looking for me.”

….With Dreamspeaker, Claude Jutra renewed a theme that he had long given special emphasis: youth. On this subject, he explained in 1970: “Youth. I am the prisoner of my youth. There’s nothing I can do about it. I think I will be always talking about it in one way or another. The more I move ahead the more I regress. When I was 30, I made À tout prendre about myself at 27. With Wow, it’s 18-year-olds. In Mon oncle Antoine, they’re 14.” Strangely enough, this phenomenon of regression with time Jutra refers to is verified all the more in his last films. Dreamspeaker features a young boy of 11, while La dame en couleurs recountgs the life in an orphanage for children between 8 and 15.

The death of an artist always involves the reconsideration of his/her work. In this article, I hope to have shed new light on certain films by Jutra that have been unfairly neglected by critics. In addition, as tribute is paid to Jutra more and more regularly in future retrospectives and repertory screenings, I hope I will have encouraged filmgoers to discover or rediscover a body of work tied together by Jutra’s personal preoccupations. The filmmaker’s English Canadian films and the various paths they reflect, taken by Jutra between 1976 and 1980, must be a part of this discovery.

Finally, in conclusion, I would like to cite a second essay published two years later on sexuality in cinema. Written while Louis was in the MA in film studies at the Université de Montréal, it specifically addresses the work of the Spanish director Luis Buñuel, and fetishism on screen. Louis had these two subjects close to his heart. The film in question was Tristana (1970), in which poor Catherine Deneuve has her leg amputated for some irrelevant reason, which nevertheless increases her attraction for her boss/husband Don Lope in the story, and outside of the story both for Buñuel and for Louis as a film critic. I quote Louis at length:

Lope renie toutes ses réflexions passées de libre-penseur, acceptant même d’épouser Tristana pour régulariser leur relation. Envers elle, il se conduit en véritable gentleman. Toutefois Tristana ne fait que le ridiculiser car, comme elle le dit elle-même, « Mieux il se conduit et moins je l’aime. » Le mariage ne sera d’ailleurs jamais consommé, Tristana refusant de partager sa couche avec Lope.

La jambe droite amputée, la prothèse… tous ces éléments iconographiques connotent la sexualité. Il y a, bien sûr, le fétichisme du pied, récurrent dans toute l’œuvre de Buñuel, que l’on se réfère à L’âge d’or ou au ??Journal d’une femme de chambre??…. On a dit de Buñuel qu’il était le cinéaste des « images-chocs », en ce sens il utilise avec efficacité la jambe mutilée de même que la prothèse. Référons-nous à la séquence où Tristana interprète au piano une étude de Chopin. Le spectateur peut en effet y découvrir en gros plan, sous le piano, l’unique jambe de Tristana manipulant la pédale…. Et que dire de ce gros plan de la prothèse mise sur le lit et sur laquelle Tristana dépose ses dessous. La jambe et la sexualité étant mutilées, la prothèse devient un vulgaire support pour les sous-vêtements de Tristana.

Le corps certes mutilé à jamais, Tristana s’enferme tout-de-même dans un véritable culte de la beauté. De plus en plus complimentée sur la beauté de son visage, elle devient vaniteuse comme le démontre bien la séance de maquillage dans sa chambre. Tristana combat son handicap physique en se faisant plus belle chaque jour. Sa vie ayant été un désastre monumental, elle tente de récupérer ce désastre par le culte de sa beauté. Si elle refuse aux hommes l’accès à son corps, elle accepte cependant d’assouvir les désirs de Saturno, sourd-met obsédé, passant la majorité de son temps enfermé dans les placards à se masturber. Certes elle lui refuse sa couche; toutefois Saturno sera le seul homme qui pourra contempler le corps mutilé de Tristana. Celle-ci apparaît rayonnante sur le balcon de sa chambre. Saturno lui fait signe d’ouvrir le peignoir, Tristana s’exécute et c’est avec un sourire extatique aux lèvres qu’elle comblera les désirs du sourd-muet. Saturno, à la fois fasciné, intimidé et effrayé, se retire derrière le feuillage des arbres.

Better than many, Louis understood both Buñuel’s perversity and his wisdom. Now that you have withdrawn behind the foliage, my dear radiant Louis, it is with your ecstatic smile that we remember you and will always remember you.

Articles by Louis Goyette.

“Jutra’s English Films.” Cinema Canada 142 (June 1987): 25-27.

« Tristana de Luis Buñuel : une iconographie riche en connotations sexuelles ou la sexualité mutilée. » In Claude Chabot and Denise Pérusse, eds., Cinéma et sexualité : actes du septième colloque [Montréal : Association québécoise des études cinématographiques/Prospec Inc., 1988, 42-51.)

CAROLE ZUCKERCarole Zucker is internationally known for her work on performance studies, and has lectured and published in Europe, the U.S. and Canada on this subject. Her areas of research interest also include the horror and fantasy genre; contemporary film theory; narrative theory; New German cinema; Japanese Cinema; aesthetics; Irish Studies; concepts of excess; adaptation, and film script analysis. She also teaches private acting workshops in Canada, the US and the UK. Her research has been supported on numerous occasions by grants from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. She has published extensively on women and the Gothic; narrative theory; postmodern fairy tales; performance theory and the history of Irish Cinema for various U.S., Canadian, and UK journals, as well as having her work extracted in The London Times. Zucker’s publications include: The Idea of the Image: Josef von Sternberg’s Dietrich Films (1988), Making Visible the Invisible: An Anthology of Original Essays on Film Acting (1993), Figures of Light: Actors and Directors Illuminate the Art of Film Acting (1995), In the Company of Actors (1999) with a foreword by Sir Richard Eyre, Conversations with Actors on Film, Television, and Stage Performance (2002), and the recently published The Cinema of Neil Jordan: Dark Carnival(2008), with a foreword written by Stephen Rea. Her latest book, Neil Jordan: Interviews is forthcoming from University of Mississippi Press, in early 2013. She has also recently completed her first feature script, Lamia.

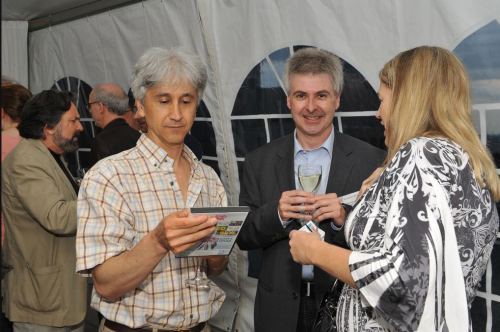

Louis Goyette was my student and then my colleague of many years. I don’t know too many people who were as generous, non-judgmental, loyal, and kind as Louis. He was a radiant presence who affected everyone he came into contact with. I know that people sometimes use the expression: “He didn’t have a mean bone in his body,” but this was really true of Louis. I never, in all the years I knew him, heard him utter a hurtful word about anyone. Louis was a great hugger, as anyone who knew him would say [see photo below for evidence, ed.!]. I know that his students felt his passion for all kinds of cinema. Louis was equally excited about music and singing, and one of the few genuine readers of poetry and fiction (rather than theories about poetry and fiction) still around. His passing will leave a huge void in the Film Studies program. We will all miss him terribly. Carole Zucker, friend and colleague.

Louis embracing fellow alumni Andrea Sadler, at Concordia University Cinema Dept. 35th Anniversary Reunion, June 9, 2011

Donato Totaro, Louis Goyette, Andrea Sadler, at Concordia University Cinema Dept. 35th Anniversary Reunion, June 9, 2011

All Concordia Reunion Photos taken by Ryan Blau

Concordia University: In Memoriam, Louis Goyette.