Play it Again: Tequila Sunrise

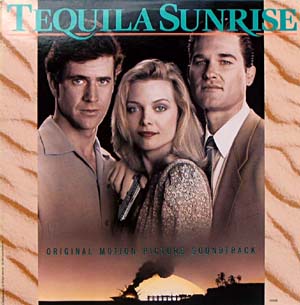

Tequila Sunrise

Cast: Mel Gibson (Dale ‘Mac’ McKussic), Michelle Pfeiffer (Jo Ann Vallenari), Kurt Russell (Det. Lt. Nicholas ‘Nick’ Frescia), Raul Julia (Carlos / Comandante Xavier Escalante), J.T. Walsh (DEA Agent Hal Maguire), Gabriel Damon (Cody McKussic), Arliss Howard (Gregg Lindroff), Arye Gross (Andy Leonard), Daniel Zacapa (Arturo, Bartender at Vallenari’s (as Garret Pearson), Eric Thiele (Vittorio Vallenari)

Tom Nolan (Leland)

Crew: Director/Writer (Robert Towne), Cinematographer (Conrad Hall), Editing (Claire Simpson), Original Music (Dave Grusin), Production Design (Richard Sylbert), Art Direction (Peter Landsdown Smith), Costume Design (Julie Weiss), Set Decoration (Rick Simpson)

TEQUILA SUNRISE (1988) is a hybrid of the romance, action and the police/detective movie genre. It might be more generically precise to call it a romantic thriller. Perhaps the clearest template for TEQUILA SUNRISE as a drama is that proposed by CASABLANCA: a romantic drama about friendship, loyalty and love, set against a backdrop of intense action, the Second World War, when lives were truly at risk and the subtext of the action is ‘what is a human lift worth?’ A melodrama, in other words. This allusion is verified by the film’s director of photography, Conrad Hall. [1]

Robert [Towne] wanted a romantic film … and I of course wanted to give it to him. I thought it should have the tone of a film like CASABLANCA. Robert is an incredible story teller. He acquaints you with a certain story and setting and opens up your juices so you are able to give it back to him with appropriate images. [2]

The screenplay for CASABLANCA was mostly written on set, from the original screenplay by the Epstein brothers and Howard Koch (and, allegedly, Casey Robinson), based on the play, ‘Everybody Comes to Rick’s’ by Murray Burnett and Joan Allison. From day to day the cast didn’t know what scenes they were shooting and nobody knew the ending until the day of shooting. However it remains, if decidedly post hoc, a masterpiece of screenwriting, blending war heroics and suspense with romance, wit and thrilling character studies. Rick is a perfect blend of epic and romantic hero, holding to blame what Andrew Horton calls his ‘core experience’ –the liaison in Paris with Ilsa, who dumped him– for his present non-committal nature. [3] The screenplay boasts some of the greatest lines written for cinema, including probably the most widely misquoted film dialogue of all time (‘Play it, Sam. Play ‘As Time Goes By.’). In terms of construction, it is based on two lines of action: the ‘letters of transit’ which helps European émigrés leave Africa and Rick’s supposedly dispassionate interest in the cause of the French Resistance, and his relationship with Ilse, the wife of Laszlo. It also boasts five subplots, all of which are introduced in Act One, helping to draw attention away from its stage origins –virtually the entire first thirty-five minutes of the films take place in Rick’s– a potentially fatal flaw.

In the same way that CASABLANCA is constructed around shifting triangular relationships (and many of their encounters take place in a public space –Rick’s Café Americain in CASABLANCA, Vallenari’s in TEQUILA SUNRISE), TEQUILA SUNRISE has a constantly moving paradigm: Mac (Mel Gibson) and Nick (Kurt Russell), Nick and Jo Ann (Michelle Pfieffer), Jo Ann and Mac, Mac and Carlos (Raul Julia). In all of these relationships truth, loyalty, friendship and love are being tested, constantly being rearranged in series and having knock-on effects on the next relationship. To this we might also add the triangle proposed by Mac, Jo Ann and Sandy Leonard (renamed Andy in the film, played by Arye Gross), whose dealings with both of them lead Nick to presume the restaurant is a front for drug smuggling; Mac, his cousin and the Sin Sisters; Mac, his ex-wife Shaleen and their son, Cody; and so forth. In other words, this structure lends itself to conflict and greater permutations of conflict in various directions. This is a hallmark of Towne’s writing, as far back as his first screenplay, THE LAST WOMAN ON EARTH, written when he was just twenty-two years old.

Narrative

The entire film is constructed on two levels: the forward movement of the investigation and Mac’s decision to act; and the backward motion to a past crime, when Mac and Nick’s friendship was replaced by that of Mac and Carlos –when Mac took the fall for a minor marijuana arrest in Mexico. It is this debt –to a friend– that dictates the constant rearranging of contemporary relationships in the film. Thus the film is posited on an unravelling double spiral, DNA-like, hinged on the possibility of love with a beautiful woman. (Towne’s second wife, Luisa Selveggio had been the proprietor of a venue called Valentino’s which the writer had frequented in the midst of his divorce from Julie Payne.) The main line of the film is complicated by the subplot, which introduces conflict for the principal characters. This could be said to occur when J.T. Walsh brings in Jo Ann to question her about the goings-on she might have witnessed at her restaurant:

We thought you’d tell us. Have you ever seen Sandy Leonard in your restaurant with a Mr. Dale McKussic?

Well, yes. They’re both very good customers.

What’s that?

bq. What’s that?

bq. A ‘good customer.’

bq. Oh, someone who’s on time and doesn’t make personal requests or demands for unusual dishes.

bq. In other words you’re telling us you never have to satisfy any personal requests from Mr. McKussic.

The implication, however vague, is unsavoury. Jo Ann’s face becomes a mask.

No, Mr. Maguire. He usually orders right off the menu …who are you and what’s this all about?

(TEQUILA SUNRISE, pages 27-28)

Critic Stephen Schiff rationalises Jo Ann’s choice between the two men (which on the surface would not appear to be a terribly enviable decision):

… the romantic triangle at the center of the movie is like a working model of Towne’s moral principles. Jo Ann cares no more for the customary definitions of right and wrong than Towne does; between cop and drug dealer, whom will she choose? The answer is: the man who, as the writer puts it, ‘lies the least.’ Towne’s characters always invent their own morality, and part of what makes his work at once utterly compelling and utterly true to the American grain is the way his people persuade us of that morality… Towne’s characters shrug off conventional mores in favor of a code that is somehow loftier and more stringent, an unarticulated ethic that reveals itself only in its heroes’ day-to-day behavior –in their deeds. His people aren’t made of the same stuff as the larger-than-life figures who now dominate the movies –they don’t save the world like Schwarzenegger or Eastwood or Stallone; they aren’t Supermen or James Bonds: ‘I don’t believe most of us have the capacity to make a change in the world,’ says Towne. ‘That’s unrealistic. And my idea in all the screenplays was to bring a different level of reality into a movie.’ [4]

Character Relationship to Structure

A key device for analysing narrative –and indeed for analysing a screenplay– is the relationship of character to structure. Let us remind ourselves of John Howard Lawson’s classic advice for all dramatic writers:

What does the character want?

Why does the character want it?

What does the character need?

By asking these questions of our three romantic leads and their roles we can understand the complex motivations and weblike structure of TEQUILA SUNRISE.

It is the sometimes conflicting dynamic between what a character acknowledges to be his goal and his unconscious motivation that drives a story forward. [5]

Screenplay analyst Linda Cowgill states that

bq. If the character’s want doesn’t drive the story, his need must.

In using this concept to analyse the construction of CASABLANCA, Cowgill finds that Rick Blane, while a superficially passive character, is actively pursuing his supposed neutrality while desiring to discover the truth of what happened between himself and Ilsa in Paris before the war began. She says,

Until he knows it, he is incapable of moving on, of becoming involved with other people, of returning to his true, former self. This need drives Rick within the plot. [6]

Rick wants to pursue his neutral role but his need for the truth alters his course of action. His discovery that Ilsa was already married to Laszlo in Paris drives him (and the plot) to the climax which sees Rick display his partisan role. Similarly, Nick wants to pursue the drugs line leading from Mac to Carlos but in doing so encounters both Jo Ann and his own loyalty to a dear friend. Ultimately, he makes a sacrifice which both counters Jo Ann’s cold-eyed view of him and confronts the audience’s preconception of him as a policeman on the make. We can see that both Ilsa and Jo Ann are the respective moral centres of their films, the pivots around whom the principals make extreme and life-changing decisions. Linda Cowgill explains:

What a character needs is often the psychological key to understanding his inner obstacles; it therefore deepens the levels and meaning of the story. How the character copes with these inner obstacles forms the basis of his development through the film because the psychological or emotional problems force the character into corners which demand new and different responses if he is to conquer the outer obstacles and attain his goal. [7]

Of course the urbane, sardonic and dispassionate (even cynical) Rick Blane in CASABLANCA is revealed to be an enormously compassionate, politically motivated, humane man capable of enormous sacrifice –even risking his life, and losing the love of his life– for other people. Cowgill describes the effect:

At its best, drama examines the costs of the protagonist’s actions, usually in terms of personal relationships. Part of the drama comes from what he leaves behind or forsakes in order to gain his goal… In CASABLANCA, Rick recommits to life and the good fight, but loses Ilsa. These costs are trade-offs; gains come from losses, losses from gains. Audiences then ask of these trade-offs: ‘Are they worth it?’

…In CASABLANCA, Rick is reborn: he changes from a bitter ex-partisan to a recommitted patriot. [8]

Cowgill correctly identifies Ilsa as a strong agent for change in CASABLANCA. [9] In TEQUILA SUNRISE, Jo Ann doesn’t have quite the same role, since Mac has already made the decision to quit drug dealing. However she has a symbolic role in that she acts in the role of benefactor and supporter, as well as lover, and takes his son Cory angel hair pasta when the boy is ill and home alone. In simple story function terms, she is an ally. The influence of Howard Hawks and his work can be seen in the way that Jo Ann comes between Nick and Mac. Jo Ann, however, is much feistier and probably cleverer than any of Hawks’ heroines and her wordplay is on a par with anyone conceived by Towne for the screen. If we view Jo Ann’s role in relation to Nick, we see that her capacity as agent for change is enhanced, which then leads to the conclusion that we are dealing with a split protagonist: Mac and Nick –who are literally split apart since Mac befriended Carlos, after the drug bust in Mexico all those years ago– and this eases our understanding of the screenplay’s construction, which is after all about the nature of broken friendship, and how it might best be repaired.

One Last Favour

The entire screenplay is constructed around Mac’s need to do his old drug buddy Carlos one last favour. This need is replaced by his need for Jo Ann –he wants to reject her and even hits her several times in the cigarette boat, so desperate is he to try to deny his love for her. He is responding to her in the same way that he has responded to drink and drugs –like another addiction that he doesn’t want to acknowledge. The empathy we have for Mac may stem from the identification that the author had for his protagonist:

Anytime you’re involved in legal matters, as I was with my divorce and PERSONAL BEST, you feel like a criminal, which made it particularly easy to identify with McKussic. [10]

The film of course is constructed as a melodrama –the form preferred by Hal Ashby, and the one which Thomas Schatz identifies as probably the most classically ‘realist’ of generic forms. [11]

Towne commented to Kenneth Turan:

I think melodrama is always a splendid occasion to entertain an audience and say things you want to say without rubbing their noses in it. With melodramas, as in dreams, you’re always flirting with the disparity between appearance and reality, which is a great deal of fun. And that’s also not unrelated to my perception of life working in Hollywood, where you’re always wondering, ‘What does that guy really mean?’ [12]

Location and Californication

TEQUILA SUNRISE can be read as another phase of Towne’s love affair with Southern California, specifically South Beach. If CHINATOWN could be read as an elegy, then TEQUILA SUNRISE is his Valentine. Towne had spent much of his childhood around Manhattan Beach on South Bay, which is the more exclusive area close to his home town of San Pedro. It’s a picturesque place, rundown in parts, but blazing sunshine and spectacular scenery in the nearby wealthy suburbs provide a stunning cinematic backdrop, with the opening and closing montages of stunning orange and yellow glimmering sunlight casting a glorious spell over the narrative, an aesthetic choice that might well have been governed by Brian Wilson’s evocative hymns to Southern California.

A Star Vehicle

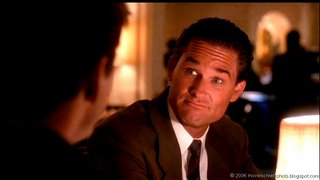

TEQUILA SUNRISE was the latest in the vanguard of features to star Mel Gibson, whose LETHAL WEAPON lead (good cop/sometimes insane bad cop) had catapulted him into the stratosphere of leading-man roles in Hollywood. He was perfect casting as an honest criminal liable to explode into drink- or drug-fuelled rage. However, he wasn’t the first choice –that was Harrison Ford, who turned it down. Likewise, Kurt Russell had been working steadily in varying action and thriller roles, most pertinently in SILKWOOD and THE MEAN SEASON, as well as proving his romantic chops opposite long-term girlfriend Goldie Hawn in OVERBOARD the previous summer. Cast as the ambiguously motivated cop who’s jealous of the loss of friendship with his former high school buddy, he shines. He should –the role was written for him. Stephen Schiff comments that, “as you read Frescia’s dialogue in the TEQUILA SUNRISE screenplay, you can hear Kurt Russell’s sneaky cadences sizzle in your head.” [13] Towne says of Russell: “In his life, he is buoyant and mischievous, a good-hearted bad boy.” [14] Russell returned the compliment at a WGA event: “it was the first time that I had read a screenplay and thought I understood it, then after spending hours with Bob, realized I understood very little about the screenplay. I had to dissect, an entirely different kind of approach to writing a screenplay. Bob demanded of the actors and of the audience that they know the character so well that when they didn’t speak it actually turned the plot. It demands the best of you, in all aspects of working in the film.” It is important to recall that his role was also partly based on the Lakers coach, Pat Riley, a friend of Towne’s. Towne said that one of his favourite scenes in his film is when Frescia clears a tray of Cokes in an explosive rage. That was based on an incident when Riley did the same to Kareem Abdul Jabbar. “’Like Frescia, he’s both calculating and emotional.’” [15] The other influence on his character was Towne’s real-life Redondo Union High school friend, who had become a narcotics officer. [16] Towne commented of the role, “He is the hero, while Gibson’s Mac is the film’s emotional center. Kurt has the Bogart part: he loses the girl, saves his friend, and he’s the one with the last line in the movie.” [17]

Michelle Pfeiffer, meanwhile, was long tagged as a superstar in waiting and her performance here followed THE WITCHES OF EASTWICK and MARRIED TO THE MOB. Her delivery of Towne’s diamond-hard dialogue surely surprised many critics who might have found it difficult to ignore her looks, which make her perfectly suited to the aggressive-passive role of restaurant proprietor. Towne said of Jo Ann that he was looking for “someone with that kind of sang froid, that kind of infuriating beauty. You wonder if this girl ever gets upset at anything. I wanted what [the newscaster] Connie Chung used to do to me with her perfect hair, saying, ‘Eight thousand people were crushed to death in Caracas.’” [18] Towne was therefore continuing his infatuation not merely with classical Hollywood generic forms but with the star system itself. Thus the film was armed with a powerhouse trio of romantic leads, aided by superb support in the form of J.T. Walsh as Hal (formerly Al) Maguire and Raul Julia as Carlos/Escalante. Maguire (as cop/villain), Carlos/Escalante (as friend/villain), Andy/Sandy Leonard (failed drug dealer and lawyer to both Mac and Jo Ann) and Lindroff (Mac’s cousin, Carlos’ victim) form a rich, dualistic array of supporting characters whose roles and traits are well-served in this complex narrative. Likewise, Arturo, Nino and the Judge (played by legendary director Budd Boetticher, presumably Towne’s form of payback for his lost role in TWO JAKES) each has startling functions and lines to perform. To quote Andrew Horton,

Each minor character exists in her/his own right but acts as a means of further defining/expanding/exploring the main determining character. They

thus enrich and complicate the main narrative. [19]

Metaphor and Theme

Just as CHINATOWN features water as a major metaphor and part of the narrative, there are very few scenes in TEQUILA SUNRISE that don’t allude to or include this element, which forms a subtext to the entire story. The film is set in the South Beach area of Los Angeles and takes place variously at Hermosa Beach, Redondo Beach and Manhattan Beach, concluding at San Pedro Harbour, a location familiar from Towne’s childhood. The entire film might be read as a recasting of his own private dramas. That the film is about drug dealing obviously gave Warner Bros. pause for thought, but as Towne reasons, “I needed an unsavoury profession for a man who was trying to escape it. The film is set in Southern California; what can you do, a stock swindle? The frightening thing is that nice and charming people do terrible things. Life would be a lot easier if every drug dealer looked like the Night Stalker.” [20]

Dialogue: ‘Whatever you’re doing, do it somewhere else’

Despite the generic construction of the screenplay for TEQUILA SUNRISE, which owes much of its structure to the 1940s melodrama, Towne’s leisurely approach allows for excellent, layered dialogue, with more than a hint of sarcasm and byplay between the actors, particularly Nick and Jo Ann. Nick’s somewhat superior attitude to Mac also gives him the opportunity to trade one-liners, such as:

You’re white. When they put your picture in the paper they’ll be able to see it.

The film contains some of Towne’s most brilliant and brittle exchanges, allowing for an expansiveness of character that is all too rare in contemporary Hollywood cinema. Director of Cinematography Conrad Hall says that,

TEQUILA SUNRISE is a story told primarily in words rather than images. The story comes out through the dialogue between the characters. Robert wrote such exquisite words for the characters to use. I felt that it was a picture that should be shot from the waist up –or even tighter. It’s basically people talking to one another. [21]

This breadth of expression gives Nick Frescia one of the longest monologues outside of Ron Shelton’s BULL DURHAM (in which Kevin Costner eulogises the beautiful things in life) and gives an insight into a man torn between duty to the law and loyalty to a friend:

Mac knows what he feels –he’s crazy about you and he doesn’t want to get caught. For a crook, it’s crystal clear. On the other hand, for a cop it’s confusing. Mac’s my friend and I like him. Maguire’s my associate and I hate him. I probably have to bust my friend if I’m gonna do my job. Now I hate that, but I hate drug dealers, too, and somebody’s gotta get rid of Carlos. How do I do that? Maguire, the creep, wants me to bust Mac any way I can, even if it means manufacturing evidence. Then he wants to coerce Mac into turning over Carlos –I don’t approve of this approach. I think I’ll stay away from blackmail and try ‘selective surveillance.’ What the hell is that? Well it’s not too complicated.

With my powers of deduction, I walk into your restaurant, take one look at you, and realize that no matter how good the food is, Mac’s not here to eat. He’s in love. He’s always been piss-poor at hiding his feelings and you’re gorgeous. [22] Then I have to wonder if you’re not feeling as smooth about concealing your feelings as you are at taking care of your customers. I know you’re not in the drug business, but maybe you’ve got guilty knowledge that can help me do my job. I check you out –you’ve had, as near as I can tell, three affairs in the last seven years– one with a lifeguard who was more a high school buddy than anything else, the other a painter from Venice, who did some frescoes in your restaurant, and the third a married man where you broke off the relationship almost immediately. You are not exactly wild and unpredictable in this area. So I figure if you’re willing to get involved with Mac, but given his interest in you you’re likely to find out what’s going on in his life as anybody else –whether you cater a party, or he brings people in here [23] –what I didn’t figure is that you’re not like me. You’re not devious. You’re honest and kind and principled and I trust you –suddenly I’m ashamed. You’re the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen, I’m nuts about you. Now …I’ve only got one question… and it’s not about Mac. I don’t want to know what you know about Mac. I just want to see you tonight. Will you? See me?

(TEQUILA SUNRISE pp.82-3)

This speech, lengthy as it is, embodies those things that Linda Cowgill states are necessary to screenplay structure:

A screenwriter uses the answers to the questions of want, why and need to define the protagonist, antagonist and other main characters as well as to build a plot. The other main characters’ wants and needs should conflict to various degrees with the protagonists’ wants and needs; they should become obstacles and complications for the protagonist to deal with and overcome. [24]

It is worth noting with reference to the length of this ‘speech’ as written and shot by Towne and Kevin Costner’s declaration of love and the sweet things in life (‘I believe…,’ a take on the American Constitution) to Susan Sarandon in BULL DURHAM (1988), that the only contemporary filmmaker writing dialogue (or to be more precise, monologues) of this nature could be deemed to be Ron Shelton –another writer who occasionally directs his own material. We might conclude that it may well be the privilege of writer/directors such as Towne and Shelton to exceed the normal boundaries of film dialogue only when they are helming their own screenplays.

Towne acknowledges his rare ability to write great dialogue:

If I have a gift, it’s that I’m very sensitive to the sounds of different voices… My wife’s voice – it’s a beautiful voice, but I’m just astonished by how much expression it carries. The movement that I hear in people’s voices affects me emotionally – it excites me; it drives me mad. [25]

It is clear from Nick’s speech that he is driven both by his want (for Jo Ann, who is falling in love with Mac) and his need to do his duty, despite his loyalty to Mac. He also has a deep need for truth. This conflict –the obvious disparity between what he wants and what he needs– is at the heart of the screenplay. As Towne himself states, “… those cases where people are sometimes talking and you realize it’s not good and you change the nature of the scene into something that is … that involves some sort of conflict and that creates compression all by itself. Just the use of conflict.” [26] Hence the importance of the speech, despite its unconventional length. It also enhances Nick’s character: although he is ostensibly the good guy and Mac is the bad guy, it is he, Nick, who is physically more suspect and oleaginous, and he also denies to Mac that he told Jo Ann about the party (which he thought was for Carlos but is actually for Cody):

bq. By the way – you told Jo Ann about the party.

bq. No, Mac. You got it backwards. She told me.

bq. Yeah? Then she got it backwards.

Well, it’s understandable – you confronting her like that – she probably got flustered. After all she’s not used to that sort of thing. She’s a very traditional girl. Wish Cody happy birthday for me.

p>. (TEQUILA SUNRISE p. 62)

This exchange exemplifies the shifting pattern of loyalties, cross and double cross, which characterises the narrative, culminating in Maguire breaking his word to Frescia and attempting to murder McKussic in cold blood, and Carlos’ attempted betrayal of McKussic. Ultimately, we see that Frescia mends his ways at the film’s conclusion, when he brings Mac and Jo Ann together courtesy of Woody in Harbour Patrol (played by longtime Towne crony and co-writer on WITHOUT LIMITS, Kenny Moore.) Towne commented: “Critics failed to see that Mac is sympathetic only to make Nick more heroic. The drug dealer is the exemplar of decency, which makes it difficult for the cop to make a choice. Nick is corrupted by his profession; the girl chooses the man who is least corrupted, the caring drug dealer.” [27]

The Scene Sequence

TEQUILA SUNRISE is built along the lines of a classical Hollywood screenplay of cause and effect linearity. “… Suddenly you’re back in a ‘40s movie, with grown-ups dressed up. There you are without even trying. I backed into it.” [28]

The story has a forward movement which involves an investigation by the LAPD and the DEA, and a backward motion averting to a past crime in Mexico, which led to Carlos substituting for Nick as Mac’s best friend. This structure is the centre of the screenplay’s unravelling double spiral hinged on Nick and Mac’s love for Jo Ann, as well as the concurrent spiral of friendship involving Carlos/Escalante. There is a series of triangular relationships constantly rearranging themselves according to the various internal dynamics and conflicts, and shifting the paradigm (and meaning) of friendship. Mark Finch, in his review for the Monthly Film Bulletin, finds that the film’s generic underpinnings are not difficult to locate:

Certain genre foundations are clearly visible, like Mel Gibson’s drug dealer who, as has many a gunfighter before him, wants to give up the business but is trapped by other people’s expectations. And the triangle has that old Hawksian characteristic of two men who can’t disentangle themselves from their own friendship sufficiently to be sure what they feel about Michelle Pfeiffer’s restaurateur – updated only to the extent that she is more impatient with the situation than any Hawks woman would have been. [29]

A key structuring element in Towne’s screenplay construction is that of the scene sequence:

Scene sequences are similar to action sequences but do not usually involve violent confrontation. Generally, they do not put the protagonist in direct conflict with the antagonist. But there is still a problem that must be faced. The scenes are structured in cause and effect relationships, showing the protagonist of the sequence trying to accomplish something. They are also structured around the meeting of an obstacle, complication or problem that the character has to deal with in the course of the plot. [30]

In TEQUILA SUNRISE, as in many of his other screenplays, Towne orders sequences around the fetish objects that tie the characters and story together: water, drugs, a lighter, a highly decorative trophy gun.

In order to explain this, let’s look at one particular sequence in the film which lasts approximately 16 minutes onscreen and commences on page 48 of the screenplay with Jo Ann in a booth at Vallenari’s with Frescia. He still suspects her of criminal behaviour and a relationship with Mac. He is shocked when she says Mac has never even asked her out.

Frescia picks up a Zippo and lights a cigarette. When he sets it down, the raised brass lettering that is worn nearly to the aluminium surface boldly reads R.U.H.S.

What’s that mean?

Redondo Union High.

You smoked in high school?

We were a bunch of rowdies, Jo Ann –-

He touches her wrist. She jumps a little.

How about an espresso?

She goes over to the bar and the espresso machine.

bq. I’ve got to lock up and I’ll never do it like this…

She doesn’t see the rain-spattered envelope by the cash register. She’s just gotten smacked in the eye with a water drop. She looks up toward the roof.

(TEQUILA SUNRISE pp.50-51)

The sequence continues to the cellar where the skylight falls in and drenches Nick. He and Jo Ann embrace in the raindrops. Meanwhile, back at Mac’s, he watches the rain with a picture of Nick and himself at Redondo Union High as a backdrop (explaining the ‘McGuffin’ Zippo which triggers the meaning of this entire sequence –friendship and loyalty.) At Lomita Station, Maguire asks Frescia where Mac’s party is being held –he doesn’t know. At the restaurant Arturo observes with suspicion when Jo Ann takes Frescia’s call and she agrees to lunch with him at the weekend. The next three parts of this montage are cut –they include restaurants where Jo Ann can dine as well as ‘checking out the competition.’ She and Frescia have lunch at a taco stand. Later at Mac’s back yard a children’s party is taking place, complete with magician. Jo Ann arrives and notes the ping-pong table set up on the second floor [this being the equivalent of ‘As Time Goes By’ in CASABLANCA –a paean to a time impossible to recapture; here, it bears meaning for the impossible friendship between Mac and Carlos.] Mac is aware that the place is being watched from the beach by twenty-five cops.

bq. Are you going to tell me that’s a surprise?

No. Mr. Frescia said there was a possibility the police would be watching you.

Did he say why?

Jo Ann finally looks at McKussic.

bq. Do you want me to be specific?

bq. I’d appreciate that.

Mac steps back inside and Jo Ann follows.

He said… you were a serious drug dealer and that you promised to quit but that you lied and were –still doing it–

bq. He called me a liar? What a bummer –well, I can’t blame you.

p>. (TEQUILA SUNRISE page 57)

Page 76 was dropped from the filmed version –Jo Ann loses her temper and says “it would have been more insulting if I’d refused to cater the party. I didn’t know it was your child’s birthday, you didn’t order the cake from us, I didn’t even know you had a child.” She wishes Cody a happy birthday. Mac and Lindroff pace the beach wondering how Frescia knew about the party before Jo Ann. Frescia can’t believe that Maguire has enlisted the Harbour Patrol in the operation. Mac calls Frescia from the beach and asks for a meeting. At dusk Mac and Frescia are sitting on a child’s swing set at the beach – and the sequence involving the lighter, the issues of truth, loyalty and friendship are explored in a dialogue that takes place silhouetted against the warmth of the evening sun. Mac says that if Frescia wants to go after Carlos, ‘be my guest. Just don’t let me catch you using me to do it.’

bq. By the way –- you told Jo Ann about the party.

bq. No, Mac. You got it backwards. She told me.

bq. Yeah? Then she got it backwards.

Well, it’s understandable –you confronting her like that– she probably got flustered. After all she’s not used to that sort of thing. She’s a very traditional girl. Wish Cody happy birthday for me.

p>. (TEQUILA SUNRISE page 62A)

A Musical Theme: The Symbolic Sounds of the Southern Californian Summer

Take another shot of courage

Wonder why the right words never come

You just get numb

It’s another Tequila Sunrise, this old world

still looks the same,

Another frame, mm…

‘Tequila Sunrise’ by The Eagles

Towne’s loyalty to his friends might be challenged by Nicholson, Evans and even Warren Beatty, but composer Dave Grusin is a constant in Towne’s work, going back to THE YAKUZA (1975.) His contribution to TEQUILA SUNRISE is to ‘fill’ those moments not embellished by the quintessential Southern California sounds that Towne chose to delineate his film. Grusin composed two songs for the soundtrack – ‘Tequila Dreams’ featuring Lee Ritenour and a theme for Jo Ann –‘Jo Ann’s Song,’ which features a solo by saxophonist David Sanborn. The film’s title is, of course, inspired by The Eagles’ eulogy to the early 1970s California lifestyle –ironically, the line that gives rise to the film’s name is dropped from page 50:

bq. Sooner or later you hear everything in a restaurant. [31]

bq. He’s never asked you out?

The only thing he’s ever asked me for is another shot of Tequila Sunrise, you’re still suspicious!

p>. (TEQUILA SUNRISE page 50)

Earlier, Frescia walks in on Mac at Vallenari’s:

Is in the midst of downing his second Tequila Sunrise. Frescia walks up.

bq. What’s good here?

bq. Everything. Why, you hungry?

bq. I missed dinner. What’re you having?

bq. A little pasta.

bq. Something like rigatoni quattro formaggi.

Almost on cue a waiter sets the enticing dish in front of McKussic, along with another Tequila Sunrise.

bq. Good guess.

p>. (TEQUILA SUNRISE p. 14)

Several pages later, Mac wants to drown his sorrows (with the eponymous drink) at home following Cody’s surfing accident:

McKussic breaks away from her and lurches toward the kitchen.

I just need some gold.

He grabs the bottle of tequila on the counter and pours it – into three shot glasses. He promptly downs one after another.

bq. Sit down, Mr McKussic.

He allows himself to be seated by her. Jo Ann kneels beside him, checks her watch. She looks at McKussic’s bowed head, trying to decide what to do.

bq. Your boy lives with you?

McKussic looks up, smiles.

bq. Depends.

bq. On what?

bq. Money and his mama’s mood –

McKussic rises and heads back for tequila, pours another shot.

Don’t you think you’ve had enough? I mean you want to hear Cody if he wakes up and needs something, don’t you?

p>. (TEQUILA SUNRISE, p. 50)

The dangers of liquid – all kinds of liquid – provide a strong thematic undertow to the material and are never far from the surface story. The soundtrack is built around the sounds of the summer –Southern Californian music is at the root of the film’s attractiveness and the songs reflect the story’s themes. Opening the film is Bobby Darin’s recording of the Charles Trenet song, ‘Beyond the Sea’ (‘La Mer’) which not only introduces us to the South Beach location, it also heralds the film’s dénouement, at a body of water in full tide. Its lyric represents Mac’s aspiration to a life beyond that which he has been trying in vain to escape. Later, ‘Don’t Worry Baby,’ a Beach Boys song sung here by the band with the Everly Brothers, underscores Mac’s fear when he can’t see Cody on the surfboard by the pier and dives straight into the ocean to save his life. Other songs have less obvious significance because of their lesser familiarity but are nonetheless thematically important – ‘Surrender To Me,’ by Ann Wilson & Robin Zander (formerly of the band Cheap Trick); ‘Do You Believe in Shame?’ by Duran Duran; ‘Recurring Dream,’ by Crowded House; ‘Give a Little Love’ by Ziggy Marley and the Melody Makers; and ‘Dead on the Money’ by Andy Taylor. The Church also contributed the song, ‘Unsubstantiated’ while El Mariachi Vargas perform ‘Las Mananitas.’ Not on the official soundtrack, but perhaps the most important musical item of all in terms of its symbolic significance, is ‘The Star Spangled Banner.’ This is playing on the radio during the standoff between Mac and Carlos on the cigarette boat – after the clock sounds three A.M. The Biblical reference is inescapable – Carlos is Judas to Mac’s Jesus. (This scene is on page 131A of the screenplay.) It alludes to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s declaration that, “in a real dark night of the soul it is always three o’clock in the morning.” Not only that, but the song emphasises that if Mac hasn’t made a decision over his ‘retirement’ from the drugs scene, he has made a patriotic choice –the United States over Mexico, the new life [and what is America but the opportunity to remake an old life in the land of the free, home of the brave] over the old-world lure of Mexico with its connotations of drug-smuggling, revolution [already essayed by Towne with Peckinpah] and gun-running.

The mythical resonance of the screenplay is completed when Mac escapes from the ocean’s life-threatening riptide (again, a warning issued on radio) and ‘walks on water’ to be born again with Jo Ann (pp.136-142), in a change to the original ending by forces outside of Towne’s control –Towne wanted Mac to die. He said to Michael Sragow, “Gibson’s character was supposed to be a moth in the flame. The real high for him was never doing the drugs but the danger of dealing the drugs. I made the guy too earnest and hangdog. He should have been more like the race horse attached to the milk truck – he hears a bell and he’s off!” [32] Instead, Mac is not only born again, ‘baptised’ as it were in the Pacific Ocean, he gets the girl. This is a highly ironic outcome, given Towne’s original opposition to Polanski’s fatalistic resolution in CHINATOWN. However, it is not true to say that this is a happy ending, per se. More correctly, it is a bittersweet or ‘mixed-emotion’ ending (as Andrew Horton says, “The cliché is that Hollywood likes happy endings. But most of the films we like best have mixed-emotion endings and fall somewhere in the middle between a ‘closed’ (completed) ending and an ‘open’ (life goes on, and we are not sure how it will work out) closing. In CASABLANCA Rick loses his true love and gains himself, and in CINEMA PARADISO Toto gains a perspective on his youth, but he realizes his youth has gone as well as his innocence about the joy and mystery of the cinema. Both of these examples suggest something lost and something gained.”) [33] We are unsure as to whether Mac has quit drug dealing –like Frescia, he is a character torn by the disparity between what he wants and what he needs, and this drives his story –his way out from the job is to sell leaky irrigation; and for Frescia, it is not an unqualified success, despite his involvement in the set up (rather like Rick at the conclusion of CASABLANCA – losing his true love but regaining a sense of self.) Water as symbol is crucial in the sexual narrative drive too: the pipe bursting in Vallenari’s, christening Nick and Jo Ann’s first clinch; the hot tub scene at Mac’s beach house, where he and Jo Ann are watched and eavesdropped, Playboy Channel-style by the police; the final, romantic embrace in the ocean when Mac is picked up by Woody and Jo Ann runs into the surf to meet him, watched by Nick. Mac’s ‘resurrection’ is complete.

Directing: The Time, the Place, the Cinematography

Once again, a Robert Towne screenplay set in Los Angeles would have a special resonance for the writer. For Towne, TEQUILA SUNRISE enabled him to return to the surroundings of Redondo Beach, where he spent much of his childhood: the entire film is set in South Bay, that stretch of coast lying between Terminal Island and Santa Monica, featuring crucial scenes at San Pedro Harbour, where Towne would have docked as a Navy man in the 1950s, returning to his home town.

bq. You know I always felt that the South Bay was like a different country…I felt that these characters belonged in that setting. [34]

Cinematographer Conrad Hall was also familiar with the area, having spent much of his student years at USC surfing on Hermosa Beach.

The whole area along the South Bay has a dazzle of light created by things like smog and aerial haze from the ocean… I wanted that incredible atmosphere on the screen. [35]

He and Towne enjoyed a particularly close collaboration with the result that the film is suffused with an unusual level of warm, sunny tones and black contrasts to bring out the light. Towne stated that:

I wanted to feel the daytime atmosphere in these funky beachy backyards… Conrad is able to capture it so well. He is a master of a desaturated daytime look. [36]

American Cinematographer reported that:

While Hall wanted the night scenes to be black and dark he wanted at the same time for the daylight scenes to be blindingly bright, like California beaches… ‘We wanted California to look hot so that the audience could feel the glow of light that the beach creates,’ Hall maintained. ‘I felt at first that the colors were too bright for the California beaches. By overexposing them some more in the printing, I was able to pale them out. I’m not sure that California will look as hot as I might have liked, but at the same time I know that it won’t look so clean and well saturated either.’ [37]

When the pair recced the coastal locations, Hall said,

The whole area down there is unclipped. It was very beautiful yet unattractive at the same time. It comes from people not mowing their lawns. I’m talking about things like weeds growing through the cracks in the sidewalk. That kind of thing. The people down there concentrate on other things they find more important. They aren’t concerned with forcing something to look beautiful. [38]

Hall explains the rationale behind the decision to employ the Color Contrast Enhancement process in American Cinematographer as follows :

The CCE process is wonderful because it allowed us to see into the shadows. By putting black into the picture, it gave the print more contrast without destroying the clarity. By picking up the silver iodides, the process eliminates whatever grey coating there is over the shadows. You can now see whatever was visible in the black before it was covered over by the grey. We did a lot of tests with the CCE process and found that it could correct things that we couldn’t do in the timing. For example, the ending of the picture takes place at night in the fog. Unfortunately we found out that fog turns out to be sort of a blue color at night. If you take the blue out of it in the timing you are liable to hurt the skin tones. I wanted the fog to look romantic and this meant it needed to be white. The tests we did with the CCE process were absolutely stunning because the fog came out white –exactly what we wanted. For me, the CCE process improved the visual impact of the film at least 30 per cent. [39]

However, as an addendum to this reportage, the magazine’s Editor says that “at the last moment, the producers decided not to use the CCE process in the release prints.” However it demonstrates Towne’s commitment to the film’s pictorial quality, which inevitably plays a part in expressing the film’s point of view – nostalgia, in its traditional, Greek, meaning, a desire for home.

The production designer, Richard Sylbert –another associate from years ago on CHINATOWN– built Vallenari’s, the restaurant where much of the action takes place, in a warehouse in Santa Monica. The film expressed yet another phase in Californian mythology for Towne:

The road houses and places like Lowry’s had collapsed, just in the last five to seven years. The advent of these restaurants is almost emblematic of a way of life. [40]

Hall comments:

The restaurant was absolutely wonderful to shoot in … Dick Sylbert built a remarkable set. It was a place I would have loved to have eaten in. The colors were wonderful. Dick painted the walls his favorite color – a sort of sandy yellowish tan [a reference to the colour scheme on CHINATOWN]. It was the same color he used to paint Paramount Studios. The room was done in browns. It was simple to light because there were enough places to hide things. I devised the lighting for the restaurant all from the floor. We didn’t have any parallels or grids so you couldn’t light anything from above. When I read the script I knew that there wasn’t a lot I could do in the restaurant without drawing attention to the camerawork. For me it became a question of how complete the coverage was going to be. I tried to figure out questions like whether we wanted to begin the scene at a waist size and then move into a shoulder size because of what was happening in the drama. I can only think in terms of the camera after I have seen the actors and how they are performing the scene. I can’t really predict where the wonderful moments are going to be because it’s all in the performances. Only the drama can mandate how the camera is to be used… .

It could be argued that Hall’s contribution to the film mirrored the influence that we can detect in Towne’s work from his years with Hal Ashby, the ‘non-directing’ director: allowing the actors to dictate the scene,

For the most part I felt that a quiet camera was important … I didn’t want to be dollying around or any of that kind of thing. I wanted to save movement for times when there was a particular reason. I used movement to try to get to know someone better by moving closer to them, as you would see in real life. In TEQUILA SUNRISE there is hardly any movement with the camera at all. I learned that lack of movement doesn’t necessarily make for a static picture. The drama is always moving forward. It’s a visually quiet picture and that’s good for this material.’ [41]

Towne illustrates Hall’s approach with an on-set anecdote:

I’ll never forget the day we shot a scene in which Mel and Michelle are sitting next to the steel mobile home in McKussic’s back yard. Conrad had beautifully lit a bed of pink bougainvillea that was very hot on camera-left during Mel’s close-up. We went through a couple of takes on it and it seemed that Mel didn’t completely hit his mark each time. At the end of the day Conrad looked pretty forlorn and I asked him what was wrong. He told me that the bougainvillea was never in the shot. Mel was doing so well that he just couldn’t say anything. Conrad didn’t want to disturb the performance. Conrad had worked so hard to have the aura of bougainvillea that we had talked about. He was very upset when it wasn’t there. [42]

Critical Response

The film was released 2nd December, 1988, the same month that Towne delivered his second version of TWO JAKES, now entitled THE TWO JAKES. Richard Combs, writing in the Monthly Film Bulletin, echoes a number of critical voices in his commentary on the film:

TEQUILA SUNRISE gives the disquieting impression of a film that has been much worked over by a script doctor, but the original premises or possibilities of which have long ago been lost sight of, or were too slight to begin with. This kind of groundless elaboration, with characters and plot detail treated with loving circumspection, but basically floating in a void of their own, was noticeable over ten years ago in SHAMPOO. There it had some thematic justification…But TEQUILA SUNRISE promises something more integrated, a romantic triangle in the specific environment of Los Angeles’ South Bay, with two of the characters negotiating an old friendship from opposite sides of the law, an old debt turning in new guise, and some bittersweet reflections on the manipulative or inscrutable nature of love. [43]

Combs complains that “Towne writes each of these characters to death, giving them endless scenes in which to mull over, or hover over, their feelings, he never establishes a compelling romantic context for them.” Furthermore, he claims that Mac remains “an amiable blur.” [44]

As for Towne the director, Combs writes, he “does no more than indulge his seafront locations as much as he does his characters.” Roger Ebert, while offering some generous appreciation, also has this to say:

[There are] so many devious plot developments that at times we miss what’s on the screen because we’re still trying to figure out what the previous scene was revealing…The Gibson character is especially intriguing because he presents such a mystery; even at the end of the movie, we’re not quite sure whether he had really retired from the drug business, or not. But there are times when the movie seems to be complicated simply for the purpose of puzzlement, when additional layers of confusion are added as a sort of exercise having nothing to do with the plot. And the central surprise in the movie –the one big amazing revelation that stuns everybody– is so unlikely that you start scratching your head. TEQUILA SUNRISE is an intriguing movie with interesting characters, but it might have worked better if it had found a cleaner narrative line from beginning to end. It’s hard to surrender yourself to a film that seems to be toying with you. [45]

His review contains an astute analysis of Towne as writer:

In his movies, the plots turn and twist upon themselves. Nothing is as it seems. No character can be taken at face value. We learn more about the characters when they’re not on the screen than when they are. And even when we think we’ve got everything nailed down, he pulls another rabbit out of his hat, showing us what fools we were to trust the magician. [46]

The TIME OUT FILM GUIDE reviewer appreciates the writing strengths behind the film before issuing a caveat:

The set-up has the precision of fine needlepoint, picking out the plot outline before embroidering it with a complex pattern of interwoven relationships… Sadly, when [Raul] Julia shows up, this fascinating exploration of the limits of friendship, loyalty and trust gives way to explosive action and empty pyrotechnics. [47]

The film would eventually gross a highly respectable $41,292,551.

AUTHORSHIP

TEQUILA SUNRISE may well be the quintessential Towne script – a meditation on the value of true friendship between men, both trapped and ultimately compromised by their respective occupations; a hymn to a place the writer loves; a reworking of a genre infused with great character detail, metaphors and motifs; and expansive sequences that elaborate on textual concepts, slowly but surely building up to a mission statement: be true to yourself. In a strange way, the film’s subject matter is a throwback to Towne’s earliest filmed screenplay, THE LAST WOMAN ON EARTH –a woman comes between two possessive men in an area filled with danger: what is South Beach if not fraught with danger both natural (the riptides washing both Cody and McKussic offshore) and unnatural (drugs and guns)? The watery ending, in every sense, may have been foisted upon him by the studio but it continues to link his filmmaking with that of Hal Ashby –in her review of EIGHT MILLION WAYS TO DIE, Pauline Kael refers to Ashby’s penchant for ‘visionary, watery finales.’ [48] The ‘noir love triangle’ in LAST WOMAN ON EARTH (1960) was filled out with the actor Edward Wain (aka Robert Towne) playing a lawyer. In TEQUILA SUNRISE, not one, but two characters feature who look like the young Robert Towne in that film – Arye Gross as drug-dealing lawyer Andy/Sandy Leonard and Arliss Howard, playing McKussic’s cousin, Lindroff (which at the very least causes the viewer some momentary confusion). At the time of the film’s release, Towne claimed to be writing two screenplays –a third instalment in the CHINATOWN trilogy, and another, about no-fault divorce in California, a traumatic experience in Towne’s own recent past. The entire story of TEQUILA SUNRISE betrayed Towne’s bewildered hurt at the price paid for lost loyalties and friendships, however misguided. Sometimes art imitates life, imitates art.

Complicating the issue of Towne’s authorial signature in his homage to Forties Hollywood, Howard Hawks and THE BIG SLEEP, and the concept of the screenwriter as author in general, is the fact that Towne allegedly did not in fact originate the idea for TEQUILA??… on his own. The first treatment and twenty-five pages of the screenplay were written in 1980 in collaboration with Peter Peyton, who successfully sued Towne and Warner Brothers in Los Angeles Superior Court, shortly after the film’s production commenced in March 1988, for $250,000, the amount he claimed he was promised in an oral agreement with Towne in exchange for a producing credit (which he never received). The issue of authorship is further complicated by the emergence of the script doctor’s script doctor –on New Year’s Day 2006 The Los Angeles Times carried an interview with an lecturer in English at Orange Coast College, Anna Waterhouse, by Dana Parsons, under the headline, ‘This Reward Wasn’t in the Script.’ [49] Ms Waterhouse, it transpired, had worked for several years as a consultant to Robert Towne. Specifically, she had consulted initially on ??TEQUILA SUNRISE and subsequently, MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE and WITHOUT LIMITS. She said of the screenplay for TEQUILA, “I found things in it that needed to be fixed,” Waterhouse says. “Lines that didn’t quite go, some technical things I didn’t think would happen in those circumstances.”

In a letter to this author, Ms Waterhouse, also a working screenwriter, states:

I think to use the term ‘script doctor,’ when it comes to my work on Robert’s scripts, is to be a bit misleading. He didn’t need surgery —simply, as I stated in the interview, someone to serve as editor (to cut and restructure) so he could focus on writing without immediately engaging his own internal editor. It gave him the freedom to, for example, write dialogue without worrying if it went on too long, or even if said dialogue would be better placed elsewhere. He was always active in the process –he never simply handed me his work to do with as I chose. He wrote, I read, then I suggested– and he agreed, disagreed, or came up with other ideas, which we would then discuss.

The truth is, Robert is a fascinating combination of the solitary writer and the ultimate collaborator. What he creates, he creates on his own. But he loves nothing better than to share his writing (reading scripts out loud, for example, to friends, co-workers and family) in order to get that immediate input (where do they seem rapt? where does he lose them?) that a stage actor is privy to. In the same way, he prefers to have someone he trusts read over his scenes. Since I left (in 2001), his favorite collaborator has been his wife, Luisa. (She would, no doubt, have been his favorite collaborator all along, were it not for the fact that their daughter was small, and it was hard for Luisa to have the time and focus that the work necessitates.) [50]

Whilst not forthcoming about the precise nature of her contribution to Towne’s screenplays, presumably because of its confidential nature, Ms Waterhouse points to an aspect of Towne’s professional character which might be traced throughout his oeuvre: his willingness to take on board outside opinion and integrate the audience’s need for story logic into his writing. The collaboration with Luisa Towne certainly can be verified by her presence and participation in the story meetings for EIGHT MILLION WAYS TO DIE, according to the production memos seen by this author at the Margaret Herrick Library. [51] This of course adds weight to the debate against the singularity of any claim that might be made for his unique authorship.

Rumours abound that this film was recut against Towne’s wishes. The ending was certainly altered: Mac did not disappear into the deep blue yonder in order to allow Frescia to get the girl. It is, as can be seen, a highly complex piece of mythic and character-centred writing, thematically rich and awash with astringent dialogue. It may well be his masterpiece. A director’s cut would be something to relish.

Primary Sources

TEQUILA SUNRISE shooting script by Robert Towne dated January 14, 1988. The cover indicates that there were 12 revisions, the first dated 02/08/88, the last is recorded on 03/04/88.

Thanks to Greg Walsh at the Margaret Herrick Library, AMPAS, for article research.

Endnotes

1 Hall shared Towne’s TV history, since both men worked on THE OUTER LIMITS series in the 1960s.

2 Marc Daniel Shiller,‘Triangle of Mistrust in TEQUILA SUNRISE,’ American Cinematographer, January 1989: 49.

3 Andrew Horton WRITING THE CHARACTER-CENTERED SCREENPLAY. Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1999: 9-11.

Fn4. Stephen Schiff, op.cit.: 41

5 John Howard Lawson, THE THEORY AND TECHNIQUE OF PLAYWRITING AND SCREENWRITING. New York, Garland Publishers,1985: 168.

6 Linda Cowgill, SECRETS OF SCREENPLAY STRUCTURE How to Recognize and Emulate the Structural Frameworks of Great Films. Los Angeles, Lone Eagle Publishing, 1999: 46.

7 Cowgill, op.cit.: 47.

8 Cowgill, op.cit.: 49-50.

9 Cowgill, op.cit.: 58.

10 Turan, ibid.

11 Schatz, 1983: 276.

12 Turan, ibid.

13 Schiff, op.cit: 41-2.

14 Turan, ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Anne Thompson, ibid.

17 Turan, ibid..

18 Turan, ibid..

19 Horton, op.cit.: 56.

20 Turan, ibid.

21 Shiller, op.cit:: 49

22 Kurt Russell doesn’t say this line in the film.

23 This phrase is not in the film.

24 Linda Cowgill op.cit.: 46.

25 Schiff, ibid.

26 Speaking at the AFI’s Harold Lloyd Master Seminar, as before.

27 Towne in Anne Thompson, ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Mark Finch, ‘Tequila Sunrise,’ Monthly Film Bulletin, Vol. 56, No. 664, May 1989: 153.

30 Cowgill, op.cit.: 174.

31 This might well be Jo Ann’s echoing of Rick’s classic world-weary line of feigned indifference in CASABLANCA, “I stick my neck out for nobody.”

32 Michael Sragow, ‘Return of the Native,’ New Times Los Angeles, 3-9 September 1998:. 17. He said to Joel Engel on the same subject, “It had great tone, because the tone that was lost came from this guy who wanted out of the dealing game, but at the same time, like an old race horse tied to a milk wagon, the bell rings and he wants to run. There was excitement, and the action was fun; he couldn’t help himself. That meant that, in the end, either he or the girl was going to get killed. There’s no other way out. It would have been a great movie. ..[Warners] will always feel that they made more money because of it, and I will always feel that they would have made more money if they hadn’t. He would have been a more romantic figure had he died. After his death, the character played by Michelle Pfeiffer takes care of his kid.” (Joel Engel, SCREENWRITERS ON SCREENWRITING. New York, Hyperion, 1995: 220-1.)

33 Horton, op.cit.: 128.

34 Shiller, op.c