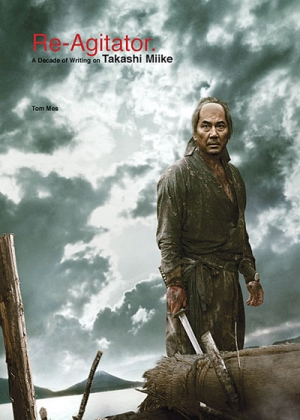

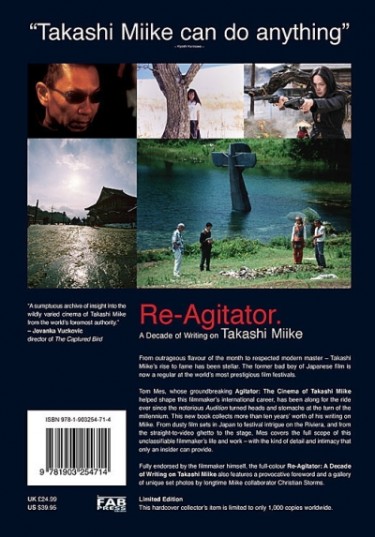

Book Review of Tom Mes’ Re-Agitator: A Decade of Writing on Takashi Miike

Author's Second book on Japan's Highly Idiosyncratic Director

“Damn the Dutch and their perfect English and their 1-nil victory over Japan in the 2010 World Cup!” (8). So ends the opening of Christian Storms’ introduction to Tom Mes’ Re-Agitator: A Decade of Writing on Takashi Miike. Storms has been Miike’s interpreter and collaborator for some time, and this is a bit of tongue-in-cheek praise for Mes, the Dutch author who, Storms claims, is often more eloquent in discussing the films of Takashi Miike than the director himself. But the praise comes with a price: Mes’ eagerness to make sense out of Miike’s oeuvre –clearly on display in his 2003 book _Agitator_— could easily be criticized for reading too much into the work of a director who refers to himself as more hired gun than artist. It is no secret that the auteurist approach to film criticism has fallen into disfavour of late within the field of film studies, and no director would seem to challenge the premises of auteur-based criticism more than Miike with his wildly variable output across a wide variety of production contexts. Yet Mes manages to navigate these troubled conceptual waters expertly, rising to the challenge of accounting for the work of this maddeningly diverse filmmaker without falling into the trappings of over interpretation or overdetermination. This feat is achieved primarily thanks to Mes’ understanding of the filmmaking culture in which Miike has been operating all these years, and an excellent grasp of the reception contexts into which the films have been set loose. In the end, Storms’ evocation of Mes’ mastery of the material seems warranted.

But buyer beware: Mes is clear from the outset that Re-Agitator is not intended to be a sequel to Agitator, and readers going in expecting the same depth of analysis found in the previous volume will be disappointed. Mes’ earlier book, about which I wrote in my review of Miike’s films at Montreal’s Fantasia Film Festival in 2003 (linked below), was the first and still solitary attempt to conduct an exhaustive study of the director’s work. Agitator is an impressive volume, systematic in setting up key themes and stylistic elements in Miike’s first 49 films followed by a through-composed case-by-case study of each film – an outstanding achievement, and still unparalleled in the sparse world of Miike criticism outside of Japan. Re-Agitator is a different beast: a collection of Mes’ writings on Miike over the last ten years drawn from a variety of venues. As such the new book simply cannot offer the same level of analysis found in the earlier one, but it is also free of the burden of the holistic coherence sought by the earlier volume and offers tantalizing insights into a couple dozen of Miike’s films, most of which were made after the publication of Agitator. So, in that way, the book does serve as something of a follow-up to the first volume for anyone interested in Mes’ take on Miike’s more recent output. But the joys of Re-Agitator are of a different order than the earlier book as it offers a great deal that the comprehensive approach taken in Agitator necessarily precludes.

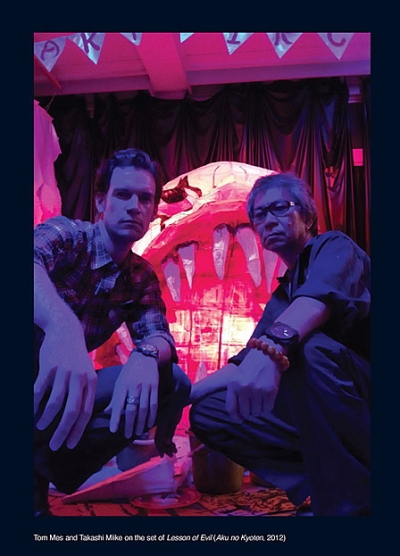

One of the book’s strengths is that it provides several different kinds of writing that allow for varying approaches to the material, including: up to the minute notes for festival catalogues featuring Miike’s film du jour; DVD liner notes for new releases of older films; insider accounts of Miike’s festival appearances; an interview with Miike (though Agitator featured one of those as well); and a variety of commentaries from Mes’ own Midnight-Eye website, Film Comment and various other publications. But given the variety of sources from which this material has been culled, it is necessarily a mixed bag. There are a handful of throwaway pieces that do little more than call attention to the existence of a film. And there are a handful of truly fascinating pieces: a chronicle of Miike’s adventures in Cannes and Berlin; an essay on the V-cinema scene in Japan that made Miike’s early work possible; notes on a Miike tribute CD and a stage production of Zatoichi; and extended multi-faceted coverage of The Great Yokai War, Sukiyaki Western Django and 13 Assassins. In between we find new takes on older staples like Audition and Ichi the Killer, and the book is a gorgeous production with colour plates throughout featuring poster art, film stills and exclusive behind-the-scenes footage of Miike at work. The presentation alone is well worth the cover price, which can be said of pretty much any book from FAB Press. Without a doubt, they’ve done it again.

The most interesting aspect of the book’s organization is that the pieces are presented in the order in which they were written, not the order in which the films under discussion were made. So Mes abandons the compulsively linear trajectory through Miike’s work taken in Agitator, allowing a kind of tango through the films as he jumps forward and back through the director’s catalogue. The most potent benefit of this organization is that we can follow the progression of Mes’ thinking about Miike since the publication of his first book. While Agitator crystallized around Mes’ take on Miike in the early 2000s, Re-Agitator finds Mes changing his take over the years, and these changes say as much about Miike’s continually transforming art as about Mes as a critic. “Films have this wonderful quality of changing along with the person watching them,” Mes writes. “New qualities surface, weaknesses have become strengths” (139). Mes is happy to put his own transformations of thought on display in this collection as he attends to new facets of Miike’s work, offering a level of self-reflection that is rare in criticism of any kind.

The first few sections document Mes’ early obsession with drawing attention to subtler shades of Miike’s work in an age when audiences outside of Japan knew him only for the more extreme elements on display in Dead or Alive and Audition. Here he continually returns to Bird People of China (a personal favourite of mine), Blues Harp, and the Black Society Trilogy consisting of Shinjuku Triad Society, Rainy Dog, and Ley Lines. Here we are close to the tone of Agitator that, as Mes reminds us in his preface, was written to document films that it seemed most of the world would never see. Thanks to the foresight of programmer Tony Rayns, I was lucky enough to discover and fall in love with Miike’s work through several of these films presented at the Vancouver International Film Festival in the late 90s before the director’s explosion on the international scene a couple of years later. So when I first read Agitator, Mes was preaching to the converted in his insistence on these earlier films as necessary to a proper appreciation of Miike’s talents. But since Miike’s subsequent international success has led to wide DVD availability of a good chunk of his output in the years since Agitator, Mes’ goal in writing about Miike has now changed as he is tasked with the increasing challenge that Miike’s newer films pose to any attempts at an auteurist reading. As we travel with Mes along his journey of continually rediscovering Miike, his writing makes it clear that it is increasingly important to evolve with the director and to understand the shifting contexts of his working environment. Thus the latter half of the book is mainly preoccupied with attending to the context of film production in Japan and how it has changed drastically over the last ten years, attempting to account for the perceived changes in Miike’s style (which some would describe as the wholesale abandonment of the elements that early fans fell in love with).

There are a few down sides to a book like this. Reading it straight through results in quite a lot of repetition as consecutive one-off pieces, originally presented at a distance from one another, end up making many of the same points in quick succession –but this can hardly be avoided in a collection like this. Slightly more troubling are the contradictions that emerge when similar pieces destined for different audiences are placed side by side. For example, the book’s early tone of exposing film goers to a more subtle and nuanced Miike regularly invokes the opening and closing sequences of Dead or Alive and the conclusion to Audition as examples of the kind of excess that we need to look past in order to find the Miike that Mes appreciates most. Thus at one point Mes insists that Ley Lines should be the go-to film for an introduction to the well-rounded Miike, a film he describes as being “sheer genius” from start to finish rather than just a container for catchy bookend sequences that prompt extreme reactions (36). But then a few pages later Mes is busy defending Dead or Alive as a film that shouldn’t be “whittled down to an opening and a closing scene” because “both scenes are functional elements of the whole” (42), an argument he later makes about Audition as well. So depending on which piece you read you will find Mes’ emphasis differing in ways that are not always entirely compatible. In part this is simply Mes doing the work he’s commissioned to do: to make whatever film he’s writing about sound as important as possible. Often this means defending work that has been overlooked, underrepresented or maligned by critics and/or fans, sometimes at the expense of more beloved titles. Other times he needs to celebrate that which is already well known by finding something new to say about it. In the end his differing takes on the same films shed light on the role of the critic in a filmmaker’s career as well as the effects of time on one’s own responses to the films.

Mes also reveals something of a selective memory, as when he points to Dead or Alive 2: The Birds as “gentle in terms of story” and decidedly more subdued than the first film in the trilogy (43). To contrast with the explosiveness of the first film’s finale, Mes cites a scene in the second film in which the hit-men protagonists, visiting the island of their youth, don furry animal costumes to perform a play for a group of young children at the school they once attended. “Who still cares about explosions after you’ve seen that?” asks Mes (43). But what the author forgets to mention is that this scene plays out with continual crosscutting between the children’s play and a violent yakuza clash that contains the most explicit violence of the entire film and is here closest to its predecessor. I say “forgets to mention” because in Agitator Mes explains this crosscutting in detail and argues for the importance of this strategy in prompting audience reflection upon how the innocence of childhood could give way to the cold blood required of professional assassins –a reflective moment that sets up the film’s conclusion in which the hit-men decide to continue their profession but donate all the proceeds to charity. These are the kinds of details that get lost with the brevity of the entries and lack of through-composition in Re-Agitator. But they also speak to Mes’ shifting attention as he revisits older Miike films in light of more recent work. And this emphasis on the more joyous side of Miike’s work, while leaving the atrocities aside, is a recurring preoccupation of Mes’ later writings. This is most pronounced in his piece on Ichi the Killer in which, after the detailed analysis of its violence in Agitator (which I consider to be the best criticism in that book), he now focuses on its profound beauty.

On the up side, Re-Agitator is perhaps most valuable as a much-needed (though necessarily fragmented) account of the changes apparent in Miike’s oeuvre over the last decade, and charting these waters is the dominant preoccupation of the latter half of the book. It’s amazing to think of 2003 Miike as being already so heterogeneous that the main task of Mes’ Agitator was to find coherence in the mayhem. Ten years later the director’s heterogeneity has increased exponentially. Looking back, it’s clear that Miike’s first decade was dominated by the yakuza genre, whether full-blown tales of gangland warfare or the myriad related films in which yakuza characters are integral to stories that diverge from genre expectations (like Bird People in China). But as Mes notes, with the 2003 film Yakuza Demon, released just after Mes’ book hit the shelves, Miike seems to have bid adieu to the staple of his formative years. In the chapter on Japan’s V-cinema market, one of the book’s best pieces, Mes explains the shifting market dynamics that have necessitated changes in Miike’s subjects and styles. In the bubble economy of 1990s Japan there were numerous investors helming small production companies that allowed many direct-to-video filmmakers to transition to theatrical productions –as Miike did in 1995 with Shinjuku Triad Society. Here the yakuza genre flourished, and as long as films fulfilled a set of genre expectations then filmmakers were free to treat the material however they wanted. And so we found Miike turning out endless gangster fare with his own particular flair. Mes contends that these conditions have vanished in the austerity of the last decade, and in their wake we find increasing domination by big studios and new market realities. A review of Miike’s later output makes the shift clear as yakuza dominance yields to period Samurai pieces, fantasy and sci-fi outings, films for children, and adaptations of popular Manga and TV series’. Mes rightly finds it remarkable that Miike has managed to keep working and to keep making his authorial voice heard through the demands of the ever-shifting market, and the book is peppered throughout with details that put the author’s expertise in Japanese cinema culture well on display.

For my money, however, the book shines best in its coverage of the mid to late 2000s, the most interesting period in Miike’s career for me, the moment when it seemed that the director’s shift to larger budget studio fare was paralleled with an increasingly experimental bent. For every One Missed Call, Zebraman or Crows Zero there was a Gozu, Izo or Big Bang Love: Juvenile A. Readers of my regular Offscreen coverage of Miike’s entries in the Fantasia Film Festival know that this was the last period that I have been able to get excited about Miike’s work, an increasing sense of uncertainty fueling anticipation as audiences who saw 3 or 4 new Miike films each summer experienced the paradoxical simultaneity of his work in this era. Mes deals admirably with material that is arguably Miike’s most difficult to grasp, and has some fascinating stories along the way. Particularly exciting is his insider coverage of Miike’s first trip to Cannes with Gozu, his direct-to-video transition out of the yakuza era that somehow found its way into the festival’s director’s fortnight. Mes reports on Miike’s pleasure at discovering that a film he thought would be lost to non-Japanese audiences could be appreciated at such a festival as Cannes. The book’s interview with Miike was conducted during this period of heightened experimentation and Mes questions him about his intentions to continue in this vein. As you would expect, Miike brushes the apparent trend off by saying that he doesn’t have a specific preference for the kind of work he takes on, and would be happy simply to continue being offered a diverse range of projects (60-63). Sadly, it would seem the opportunities to experiment have dried up and we are left now with a predominantly industrial Miike.

I must admit that I am one of those early fans now “grumbling from the terraces of late about the recent state of one Takashi Miike” (123). Why can’t we have the Miike that once was? Or at least one that continues to stimulate in the same way? Mes’ answer lies in his unpacking of the industrial realities in which Miike works. If there is one overreaching argument in Re-Agitator it is that Miike is alive and well, continuing to be himself, putting his own spin on whatever material is available for him to direct. “It is not Takashi Miike that has changed, but the industry around him” (123). But this argument is not entirely satisfying to me, especially since one of the justifications for this book is Mes’ emphasis on how his own personal changes over the last ten years have affected his criticism. Mes’ suggestion that Miike hasn’t similarly changed seems overstated, but never mind. Regardless of the extent to which Miike’s own personal changes have interacted with the industrial shifts that surround him, I haven’t as of yet appreciated the newer Miike to the same extent as various former incarnations. Yet in the end Mes says it best: “To wish for Miike to go back to cranking out Dead or Alives and Auditions on a bi-monthly basis is like wishing for tomatoes to still taste the way they did before your country joined the European Union – that era, I’m afraid, has passed” (123). And it is to Mes’ great credit that the insight he provides into Miike’s later work is prompting me to revisit some of the films that I didn’t care for on first viewing, seek out a few that I’ve missed over the years, and go into the new stuff with an open mind. Just as I was feeling okay about leaving the tomatoes off my salad altogether, Re-Agitator comes along and kindles my desire to give the new breed a fair shake. Damn those Dutch indeed! Or at least the one called Tom Mes. Good thing Fantasia 2013 is just around the corner…