Strangers and Friends, Immigration and Power, in the film The Visitor

Haaz Sleiman “radiant”; he and colleagues create believable people

(for Tom Buckman)

Each human existence bears relation to history, and to the culture and politics of its time. In the film The Visitor, an alienated American man of European descent encounters immigrants, from Syria and Senegal; and his assumptions are challenged and his life enriched. The American man is educated, knows about history, culture, and politics, but his own life seems to lack joy and wisdom. There are a lot of paintings in his Connecticut house and New York apartment, but they do not seem to speak to him, nor does the classical European music he is inclined toward seem to speak to him: and he is a lonely figure, until he meets the strangers who become his friends, one of whom introduces him to new music. The principal crisis in the film involves the incarceration of the Syrian musician due to his immigration status. The film The Visitor, directed by Tom McCarthy, allows its appreciative viewers to contemplate the pleasure and rigor of music; the unpredictability of friendship; the indifference of bureaucratic power; the limits of white male privilege; and the irresolvable nature of human experience. One contemplates indifference and sympathy, grief and pleasure, suspicion and recognition, and anger and pain; and the film gives us a story that does not end and yet seems complete. Tom McCarthy, who directed the film The Station Agent, presents in The Visitor a New York that is recognizable to me, a New York of different cultures and classes, of people of differing ages; and yet it is a film that, because it does so, because it does so with depth, seems, somehow, foreign.

Part I, in 5 fragments 1.

The pleasure and rigor of music. The central character in the film, Walter, an economics professor and the husband of a pianist who has died, a pianist whose piano remains in the house and whose music remains a part of his listening, tries to learn how to play piano, though he has no talent for it. He seems not to have the discipline, the gift, or the genuine pleasure required for playing the piano; and he seems compelled by duty or nostalgia to practice, to learn. It is as if he is being true to his wife by doing what she loved, by carrying on her devotion. It is an understandable but shallow commitment (he is trying to observe the form rather than the spirit of her commitment).

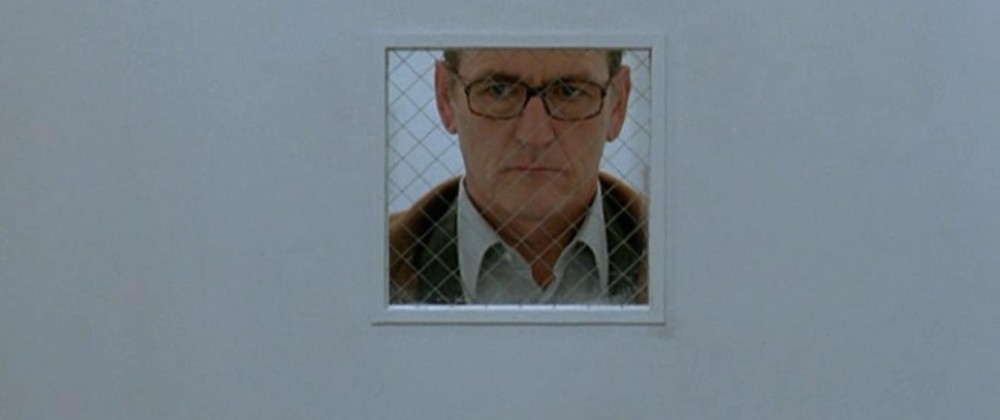

The film begins with piano music (its score), and a man, Walter, at the window of a pleasant, private home—alone, anticipating, possibly anxious: he is not young, and he may be waiting for his life to begin anew. He is, in fact, waiting for his piano teacher, his fifth teacher, following his pianist wife’s death. (He is trying to keep the past alive; and in some of the early scenes he is photographed, often, in the dark.) Walter cannot even hold his playing hands properly, and after his teacher resorts to a simple metaphor, telling him to hold his hands curved so as to leave space for the train (and using a pencil as the stand-in for the train going through a tunnel, an image that might have a sexual connotation), he decides to end his lessons with her.

However, over the course of the film, Walter does come to music: when he arrives in New York for an economics conference and finds an immigrant couple living in his apartment, he befriends them; and the male in the couple, Tarek, is a drummer (his mother is Palestinian and he grew up first in Syria), and Tarek plays the djembe, an African drum. Walter finds himself attracted to the energy and rhythm of drumming—not only in Tarek’s playing but in that of strangers he sees in Washington Square Park (black men ferociously playing, using plastic cans as drums: creativity transcends circumstance). Tarek begins to give Walter lessons; and despite whatever small foreboding Walter feels—the drum is a new instrument for Walter; and the people Tarek introduces him to are often of a culture different from Walter’s (middle-eastern, African, or African-American)—Walter allows the music to transform him into a musician and into a participant in other people’s lives. (It is interesting that when Walter first hears Tarek play in a club, Walter listens while Tarek’s girlfriend draws new designs for the jewelry she makes, jewelry she sells to nice, ignorant Americans, who seem like tourists in parts of the city: is she inspired by the music; or is she ignoring the music?) One of the most captivating scenes in the film is of Tarek and Walter playing as part of a drum line in Central Park, a scene of casual community and spontaneous spirit. Another involves a prison visit, in which Tarek plays a beat against his chest and Walter drums on a table—an inventive intimacy and unpredictable beauty. The film could be about how music is born, out of loneliness and love, out of practice and improvisation—since all we see seems to converge with Walter’s playing.

2.

The unpredictability of friendship. Walter is inclined to communicate with others from a position of authority and distance, when we first observe him. As an established professor, a longtime teacher with three published books to his name and a respectable reputation, he can coast on his reputation—teaching only one class, supposedly to concentrate on a book; and not actually doing work on a book, though no one seems to pursue that fact. It is surprising at the beginning of the film, seeing what a difficult piano pupil (if not bad student) Walter is, to learn that he himself is a teacher, an economics professor; and just as he is a difficult student he is a difficult teacher, refusing to accept excuses for late papers even though he himself has not given his students a syllabus for his course. He is a man alone, adrift, when the film begins. He has allowed his name to be used as co-author of a colleague’s paper, part of his and his college’s support for her tenure quest; and when that colleague’s pregnancy requires bed rest, forbidding her from going to a New York conference, he attends in her place; and, there, the drama commences. Walter lives in a way that doesn’t allow him to be significantly challenged, until he meets the immigrant couple, whose love, whose precarious existence (in terms of money and housing and citizenship), and whose music begin to engage him.

Walter arrives, initially, in his New York apartment with a wine bottle in hand, along with his suitcases (we have seen him drinking alone in his Connecticut house). He notices fresh flowers and a portable table he does not recognize. After all realize that the immigrant couple have been renting Walter’s apartment for two months from someone he does not know (illegally; a scam), Walter allows them into his life—and with simple activities (shared meals, listening to Tarek perform his music in a nightclub and then practicing with Tarek), Walter does become a friend to them, not only in appearance or in word but in deed. The couple may remind him a little of himself and his wife (a photograph of them together, a souvenir of a past moment, seems to be what reminds him). Walter cares about the couple, he shares his resources, and he tries to help them. Walter’s work on economics touches on issues of international relations; and Walter’s life now embodies that concern. When Tarek is arrested, it is Walter who arranges for a lawyer, an efficient Queens-born lawyer of middle-eastern descent, and Walter visits Tarek. With friendship, the couple allows Walter to become a more complete human being again.

3.

The indifference of bureaucratic power. Early in the film, as Walter drives from Connecticut to New York, to deliver the paper he has supposedly co-authored, there is a “support our troops” sign on the highway. The sign is a reflexive affirmation of patriotism, presumptuous, the kind of thing—loyalty, obligation—that governments count on; and it gestures toward American soldiers fighting in Iraq, after the unrelated (or speciously related) September 11, 2001 world trade center attack. The question is not only, What do we owe our government and its mandates; but, also, What is owed to us? Taking the subway, Tarek uses his train card to allow Walter through and is himself entangled in the turnstile, and policemen, waiting and watching policemen, accuse him of jumping the turnstile, of fare-beating, and arrest him: their response to Tarek is cold and suspicious, and, of course, when he is brought to the police precinct and it is learned that his status is not by law, he is detained. (Fear of terrorists makes middle-eastern men particularly suspect, though as Tarek says, terrorists have money and support and are not vulnerable as he is.) Even with the lawyer Walter has hired, Tarek remains vulnerable to government whim; and subject to deportation without concern for his preferences or relationships. The irony is that Tarek’s father had been a journalist, and had run afoul of Syrian authorities, and was jailed; and by the time his father was freed the man was too sick to live: the way power works is often the same, no matter where one finds one’s self (the land of refuge is no refuge).

4.

The limits of white male privilege. Walter uses his authority against a student (refusing to accept a paper) and against Tarek’s mother (refusing to describe his proposed book); and both are moments of insensitive power, lacking concern for the feeling or the need of the other person. Walter’s increasing friendship with Tarek and with Tarek’s mother softens his responses, but, despite Walter’s hospitality to both, his private hospitality, Walter’s empathy and his money do not protect Tarek when it matters most, in his dealings with public or political power. Walter assures Tarek’s girlfriend, Zainab, that they will be able to get Tarek out of detention. Why wouldn’t Walter think that? How often has his own citizenship, his own white male privilege—his money, his security, his status—helped him to get out of or remain out of difficulties?

Walter visits Tarek in detention, in an obscure part of town (a space on the margins, apart from the main life of the city). Walter encounters a bureaucracy, and an indifference to human individuality and reasons, he would not have been faced with otherwise. In the prison, there is no privacy, and the lights are always on; and babies and letters are raised to the glass partition by visitors for viewing by detainees. Control and surveillance are constants. It is humiliating for an individual, and shattering for relationships. Walter learns the limits of his own power: neither the lawyer that Walter has hired nor Walter’s direct (intellectual, emotional, moral) appeal helps Tarek. The rules regarding the powerless, such as Tarek, are what they are. What is ironic is that the guards in the detention center are African-American: so, blacks get to exert a power against foreigners that is otherwise turned against them. (The vulnerability of the immigrants is devastating, but they are also uniquely alive, partly because of it: their joys and griefs are vivid.)

And, when, at one point, Walter confesses to Tarek’s mother Mouna that Walter’s own work is not important—that he doesn’t care about teaching and is not actively writing a book—it is a confession of the now false basis of the assumptions of Walter’s personal authority: it clarifies and diminishes his social power but amplifies his personal appeal—he has become more honest, more human. (To what extent is this another “education of the white man” film?) Walter’s growth is an important step (the film will conclude with Walter embracing passion and leaving behind false privilege); and Walter’s growth is not enough.

5.

The irresolvable nature of human experience. Tarek is charismatic and confident, but his prison experience humiliates him, and challenges his sense of self and safety (his scenes of anger, fear, and pain are quite believable). It is hard for the self to be stable if one’s circumstances are not stable. Tarek’s girlfriend Zainab is a more challenging personality: distrustful, haughty, and with sorrow and possibly anger beneath her disdain. She can be alienating, until one realizes her situation (her illegal immigrant status; and why she needs to protect her privacy) and the motive for her behavior is quite clear. (She herself had been in detention for five months, when she first arrived.) She, as part of her ordinary activity, is forced to know more, to consider more, than someone like Walter does in his own daily life. After Tarek is taken into custody, she remains concerned but there are limits on how she can express that concern, for fear of being arrested too. (The girlfriend has a sense of propriety: not long after Tarek’s arrest, she moves out, going to stay with a friend in the Bronx—possibly for her personal safety and to maintain a suitable distance between herself and Walter.)

When Tarek’s mother arrives, she—also illegal—wants to know more about her son’s life and to be close to him, though she, too, faces constraints. She, Mouna, has come because her son has not called her in five days, and is not answering his cell phone; and she wants to see where he is being held, and know something of what gave him pleasure. She wants to remain in New York, though she has no associates of her own in town. Walter welcomes Mouna; and they share meals and buy each other a preferred newspaper; and Mouna likes the music of Walter’s deceased wife as well, and tells Walter that she, Mouna, likes the Broadway music her son Tarek had sent her (cultural appreciation works both ways). Mouna is surprised by Tarek’s girlfriend’s blackness, and accepts her; and the two women in Tarek’s life share tea and conversation and worry. (The mother is both warm and formal, speaking in a way that is direct and halting; and as the film continues she is a whole person, sweet and wise, and with her own secrets and yearnings.) Walter, the girlfriend, and mother go on the Staten Island ferry, something Tarek enjoyed: and landmarks are pointed out, the absent twin towers of the world trade center, and the Liberty statue. Their individual personalities, and the terms of their existence, all question something fundamental about the political order; but, I wonder, as I’ve wondered elsewhere, if people of color are allowed only political existence and political meaning? Feelings exist, despite social restrictions: as always; and the feelings we see in the film are complex—and they are not comforting.

Part II

The film The Visitor, which begins with a man waiting for a music lesson and finishes with him playing music, does something a bit quaint, and always necessary: it allows us to be part of a complete experience. I had not seen a new film in months, and though I have an inordinate affection for movies, thinking that I could see almost anything, I knew that I could find myself in a theater miserable and angry, repelled by the movements on the screen, and, consequently, I tried to be careful about my choice. The things that were being said about The Visitor made the film seem like something I might like; and luckily I did like it. The Visitor shows a world that is familiar to me; and yet it is a world that seemed strange in the cinema: the film deals with a world of people vulnerable to chance and to power, and the film’s attention to character, to social complexity, and to irresolvable realities renders it a strange work. It is rare to see these people and acts, these emotions and ideas, in an American film; and there were moments when I thought I was watching a film from another country.

The actors in The Visitor are all remarkable; and the people in the film become understandable to us because of them. Richard Jenkins, as Walter, conveys coldness and decency, enthusiasm and self-restraint. Hiam Abbass, as Tarek’s mother Mouna, creates a character that is sensitive, focused, smart, and vulnerable. The actress, Danai Gurira, playing the girlfriend, Zainab, can seem quick to anger or sadden and can look almost impersonally beautiful or ugly. The actor playing Tarek, Haaz Sleiman, is just perfect; and if there is any justice in cinema, he will make many films. Haaz Sleiman’s Tarek could teach a corpse to dance.

What else might Walter do with what he has learned? How might he write or teach differently? Is the answer, really, for each of us to become a musician or an artist?

That The Visitor leaves us with significant questions is an achievement of art, and a compliment to our intelligence. It is not simply a work that entertains our eyes and our nerves, as is much of what Hollywood produces. (I saw the film a few days before seeing a museum screening of Francois Ozon’s Under the Sand, which was similar to The Visitor in that its story seemed simple yet revealed complexity of character and situation the way literature might: in Under the Sand, a contented woman’s possibly unhappy husband disappears at the beach and she refuses to admit he may have drowned. In Under the Sand, Charlotte Rampling, who is aging beautifully, creates a woman whose life has been perfect until the foundation of that life disappears; a woman in whom both reason and madness, and humility and anger, begin to reside.) When The Visitor appeared as part of the Toronto International Film festival, the Hollywood Reporter_’s Kirk Honeycutt wrote that director Tom McCarthy “is a terrific storyteller, letting characters move into a story so naturally that the story develops and deepens his characters while their actions and behavior propel the story” (_The Hollywood Reporter, September 12, 2007). Kirk Honeycutt commended the director’s visual artistry, how he placed Richard Jenkins in large spaces and crowds in Connecticut and more intimately in New York, suggesting a greater humanity. “He both uses real locations unselfconsciously and discovers their pockets of poetry,” asserted Michael Sragow (The Baltimore Sun, April 25, 2008). Truly, while watching the film I kept wondering whether it was a difficult film to make. The attractive, comfortable homes that looked lived in and the inviting cafes, as well as the trash blowing on the streets in one place, and the two trains moving behind the characters (criss-crossing the tracks) in another, suggested verisimilitude: how much conscious choice went into what I was seeing? The director presents a believable world in which his people live; and his people breathe, think, feel, and live, and live naturally, in that world. “Jenkins is extraordinary here, not because he does anything big, but because everything he does is so economical and intuitive,” wrote Stephanie Zacharek in Salon (April 11, 2008). (“He’s always hesitating to do what turns out to be the right thing,” astutely observed the _Baltimore Sun_’s Michael Sragow of Walter.) Haaz Sleiman’s character Tarek was described as a bridge “between the taciturn Walter and the always wary Zainab” by _Variety_’s John Anderson (September 9, 2007); and it is a bridge that one can see more easily in art than in similar situations in life. (The film can be a bridge for us between different kinds of experiences.) How else are many of us to learn about the strangers in our midst? Often, the crudest explanations for other people’s choices and lives are given in our daily lives; and art, such as The Visitor, can help us to resist that stupidity.

When Walter first arrived in his New York apartment for the conference his dean compelled him to attend, and found strangers living there, he might have allowed, or forced, the immigrant couple to leave his apartment and not return, just as many of us turn our faces from strangers in need. “I knew I liked this movie when a single cut shows Tarek and Zainab back in Walter’s apartment. McCarthy could have shown us Walter changing his mind and the three of them trudging back to his place. But the vagueness of their return is actually beautiful in its simplicity,” wrote Wesley Morris of The Boston Globe (April 18, 2008). Many of us fear kindness will be exploited: sometimes it is. By showing us an unplanned kindness, the film allows us to intuit its motive and nature. Sometimes our safe isolation is a living death, as it might be for Walter in The Visitor. Wesley Morris called the film “a melodrama whose dam respectfully refuses breaks.” The film is more likely to register emotion rather than to exploit it. “It’s a film about relationships, their randomness and unpredictability, and what happens when bureaucracy attempts to make life conform to its rigid, parochial and often ignorant standards,” declared Carina Chocano, who called Haaz Sleiman “radiant,” creating a character with “uncommon warmth, openness, and humanity” (The Los Angeles Times, April 11, 2008). Individuals may be able to achieve a freedom and an understanding that it takes institutions longer, if ever, to find; and Tarek is himself an embodiment of many good things. Tarek is an easily seductive character, one not every actor can play: “He loves his art, he loves his life, and he tends to resist acknowledging the daily risks” of his illegal status, wrote Cynthia Fuchs of PopMatters.com (April 17, 2008). Tarek seems free; and that makes his imprisonment truly felt.

Yet, the film has not been welcomed by all: what is? Peter Rainer was skeptical in The Christian Science Monitor (April 11, 2008), wondering about the likelihood of Walter allowing two strangers to stay with him in his apartment; and about the need for a dull, pale man to need the spiritual rehabilitation of people of color. Rainer did appreciate that “the most emotionally piercing moments in the movie belong not to Walter but to Zainab, who cannot even visit Tarek at the immigration detention center for fear of being arrested herself. Zainab is prideful and ferocious but, faced with the loss of her love, she seems to collapse in on herself. Gurira is a marvelous actress who can express more in a glance than most performers can with a full monologue. Abbass, too, has a melancholic dignity that reaches out to us.” Rainer may err on the side of pessimism rather than optimism (sometimes what seems true to people is what seems to negatively implicate humanity). It depends how one reads his comment: is Rainer rejecting idealism or rejecting a stereotype? Rainer’s reservations were shared by Cynthia Fuchs of PopMatters (April 17, 2008): “Walter’s education is achieved by his engagement with this set of brown and black people. It’s a grating conceit, and it’s hard to forget even as the film does work so hard to show the ‘others’ not as objects of his experience, but as subjects who invite his understanding.” I can think, of course, of worse situations and stories: stories in which people of color have no consciousness, no significant talent, no value; stories in which people of color exist for sex and violence.

Part III

The value of people of color, native-born and immigrants, is not something that has been, or can be, positively taken for granted (yet): in fact, both have been subject to great skepticism. Questions regarding culture, morality, economics, and politics have affected how they have been seen and received. Do they share the culture of the dominant society? Are their moral standards lax? Do they aid the economy as able workers or drain it as lazy people taxing social welfare? Do they possess rights that must be obeyed? Do they respect the laws? Arguments can be made, and have been made, from different perspectives. In the 2004 edition of the Thomson/Gale book Immigration, edited by Tamara L. Roleff, a history of immigration in the United States is given by diverse contributors, with some arguing that people with bad characters are being allowed in, and others arguing that immigrants are more grateful, more loyal, and more law-abiding because they have chosen to come to the country; and some writers argue that immigrants contribute to culture and economy and others that they dilute and subvert what they find: the arguments that we hear now are not new. Another book, Michael LeMay’s Illegal Immigration, a reference work published by ABC-CLIO in California in 2007, notes that there are about eleven million illegal immigrants now in the United States. Obviously, such a fact would be of significant concern in the best of times and is a greater, more ominous concern when the country has reason to be concerned about its security. The USA Patriot Act, legislation passed after September 11 and affecting the civil liberties of all American residents, and admission to the country, and surveillance of citizens and residents, has resulted in harassment of people of middle-eastern origins. People are arrested on the slightest provocation and can be detained for years, with some of them deported. Obviously, that is not fair or wise, and it is certainly not efficient, as rules are established not simply to exercise power or express prejudice but to achieve particular effects, ideals and practical goals. What are Americans to do?

What else might Walter do with what he has learned? How might he write or teach differently? Is the answer, really, for each of us to become a musician or an artist?

It would seem to me that Walter could use his encounter with Tarek, Zainab, and Mouna as a source not only of emotion or energy, but as a source for new knowledge, knowledge that could invigorate his writing and teaching, giving him a new or sharper focus and purpose. Walter could actually write about why immigrants come to the United States—the economic and political promise they see in the country; and the economic and political problems they face at home, some of which the United States may be directly implicated in (a connection may exist already between the country they leave and the country to which they flee). Walter could become involved in immigrants rights’ groups, involved in an activism and politics that might directly affect how people such as his new friends are treated. In other words, Walter could use his privileged place in society for transformational work: rather than finding comfort, pleasure, release on the margins, he could have his pleasure and use his power for good in the center of society. It’s a thought.

Often American films give us endings that affirm love, moral judgment, or another ideal, such as art or friendship or maturity or patriotism, but while offering gestures in these directions—with the intimacy between Walter and Mouna, and Walter’s sense of the injustice of Tarek’s treatment, and Walter’s mastery of the drum—The Visitor does not make easy affirmation acceptable: Tarek and Zainab are separated by his detention, and Walter and Mouna say goodbye to each other; Tarek is not freed; and we last see and hear Walter playing his drum ferociously in the subway, the subway being the site of Tarek’s arrest. The film has shown us too much, told us too much, and we understand too much. The familiar life has produced a strange film, and the strange film—with its focus on four truly distinct characters and the pleasure and rigor of music, the unpredictability of friendship, the indifference of bureaucratic power, the limits of white male privilege, and the irresolvable nature of human experience—delivers us not into the consolations of art but into life, into the complexities of life.