Sisyphus and Suburbia: A Contextual Study of David Lynch’s Dumbland

Dadaist Animation

An Introduction to David Lynch and his animated series Dumbland

The last thing most would expect from any three-decade auteur would be the sudden, inexplicable release of a crude, vulgar, and satirical flash-animated comedy series focused unflinchingly upon the obscure goings on of a frighteningly bizarre über-dysfunctional family –but of course, David Lynch is not the average auteur. Staying well-grounded in his self-reflexive themes and motifs –though giddy in his surreal, playful and crass romp through the stereotypes of Americana dynamic– Lynch has released an eight episode animated series appositely and bluntly entitled Dumbland. [1] The series is certainly a work of absurdity, chronicling with zeal the hyper-violent banality of a Neanderthalian alpha-male named Randy, who terrorizes his family, neighbors, and himself, all remaining perpetually enveloped in the meaninglessness and repetition of the suburban everyday and framed within Lynch’s blackly absurd comic lens. Though the series remains rooted in Lynch’s characteristic surrealism, it plunges vastly beyond most Lynch films in its puerile humor and crudeness of medium –all of which deceptively mask the real grit of Lynch’s message: a skewering of the rotted and dysfunctional nature of the American nuclear family– a family immersed in banality, and drowning in absurdity –left only to violently self-destruct. Similar to themes explored in his short film The Grandmother, and in his films Eraserhead, Blue Velvet, and Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me [2] –all of which containing intense and nightmarish studies of the family dynamic– Lynch wishes yet again to examine the nature of absurdity, violence, and primitivism in the human condition, as well as in the family structure, using his characteristic flawless sound design, nightmarish slapstick violence, and esoteric Dadaist character behavior, with an episodic pacing and a very enjoyable disregard for any sort of polite restraint.

It is of course, however, no surprise that most critics –ranging from Lynch cult fans to structuralist cinephiles– totally miss the point of the series’ much necessary raison d’être. While structuralists attack the “crudeness” and alleged “pointlessness” of the series, using the infamous accusation of “weirdness for weirdness’ sake,” supposed Lynch fans simply relish in that alleged “reasonless weirdness,” without care or respect to any sort of real artistry or social commentary. Both camps of critical reception seem to be oblivious to the true brilliance and intensity at work here, and even more oblivious to the message, as well as Lynch’s origins: the Camus-inspired Theatre of the Absurd, the movements of Dada and Anti-Art, and the overall surrealism Lynch is perfecting, following of course in the footsteps of Buñuel and Dali. There is a lot of progression, sincerity, satire, and stark beauty in Lynch’s work –all of which impatiently ignored by critics, under the pretense of “incomprehensibility.” Lynch, however, is strikingly personal when it comes to his work –work that is more often than not extremely self-reflexive– and refuses to let any critic own his interpretation, challenging them to find their own: a radical post-structuralism and audience-trust that should be greatly appreciated, though, unfortunately, results in frustration from those who want immediate answers and understanding to everything they see –a rather languid characteristic very frustrating to the responsible cinephile. Notoriously cagey and hesitant in press conferences, Lynch remains resistant to the culture’s demand to have an easy explanation for everything, opting always to work with intuitional narratives versus logical –a rather eastern and patient approach that reflects his admiration for transcendental meditation– and refusing to fill up those beautiful pockets of vacuous ambiguity with “language” and stilted words. For to Lynch, words can never be film –and they shouldn’t try.

But Lynch’s work is by no means as esoteric as enervated audiences would have one believe. If an individual would just feel Lynch’s work versus trying to deconstruct it, new possibilities would abound, because Lynch likes to roam the hidden, layered lusts and evils of the subconscious, and certainly the meta-conscious, not simply explain them away with turgidity. Often, these pockets of ambiguous horror remain –linger– even after being filmed, which is a beautiful and stunning experience to take part in.

However, a quick look at the history and development of Dada, of Absurdism, and maybe a very surface understanding of the teachings of Freud, and already Lynch’s oeuvre begins to blossom with new meanings, layered meta-texts, and an exciting and challenging density; for though this knowledge is not necessarily needed to enjoy, it is certainly illuminating. In a filmic landscape plagued with post-modern ennui –a landscape catering to the recycling and repetition of b-movie trash (a la Kill Bill, Jackie Brown), a fascination for the visual cliché (this neo-noir phenomenon that won’t desist, e.g. The Black Dahlia), and a love for the irrelevant (art-house sentiment a la Me and You and Everyone We Know) [3] –Lynch’s work stands in stark opposition to all the popular drivel of modern film, not to mention the Hollywood mainstream movie assembly-line. His sincerity is certainly striking, though in a post-modern world where sincerity and truth are lame –and the cliché, self-conscious texts, and apathy are hip– Lynch’s work is often ignored, racked with languorous frustrations, and dismissed, if not publicly lynched –pun fully intended.

But before I go into a look at the many shocking and comical satires and texts Dumbland has to offer, I want to give a brief history of Lynch’s predecessors, which seem to have been all but forgotten in the critical realms of today’s cinematic landscapes. Structuralism and sentiment seem to abound in film today, with no real ambition for the radical and almost violent 20th century philosophical arts of Absurdism, and Dada –art forms that attack and scrutinize the very nature of the human condition. And if we are going to understand Lynch, it is necessary to study him in proper context, and not in comparative critiques to other dissimilar works of art or art genres. Lynch is a rather isolated figure today in his art –a fact that has made the term “Lynchian” a rather common denotation– though he is certainly not without origin and pretext. And while it is true that the characters and themes of Dumbland are crude, vulgar, and no doubt grotesque, we are reminded of absurdist author Eugene Ionesco, who announced, “People drowning in meaningless can only be grotesque,” [4] –and there is certainly ample fragments of meaningless within the suburban world Lynch is attempting to reflect– a world many of his films hint at, though have never penetrated the way Dumbland does. But be careful when critiquing Dumbland, for it is not so much the series that is “crude, stupid, violent and absurd,” [5] but the world it wishes to reflect. And as such, with a successful representation of the series to its absurd focal point, the series must also follow suit –as it certainly does.

A brief history of Dada, Absurdism, and the art of Anti-Art as a very necessary introduction to Dumbland:

“If it’s funny, it’s funny because we see the absurdity of it all,” says David Lynch of his series, [6] and – appropriately– let us familiarize ourselves with absurdity.

In the early 20th century, both during and after World War I, an artistic, avant-garde movement called Dada quickly and suddenly emerged throughout Paris, New York, Berlin, Cologne, and from its starting point, Zurich, Switzerland. The movement peaked between 1916 and 1920. [7] Represented by a core group of prose and theatre writers, as well as musicians and crude sculptors, Dadaism was, essentially, “an international artistic and literary cult” that violently and nihilistically protested against –via art– “all aspects of Western Culture,” especially war, as well as the bourgeois values thought to have caused it. [8] The main inspiration for this violent artistic protest would be, of course, the first World War. The advocates of Dada saw the very existence of this “grotesque” and “evil” war as proof that society had corrupted the inherent moral goodness of the human being, and that the human, who is immersed in this rigidly exploitative and morally vacuous society, must be exorcised and saved from his or her decayed surroundings. [9] As such, this corrupting and rotten Western Society, the origin of evil capable of causing something like the World War, should be destroyed, reexamined, transvalued –hence the attack on all artistic and societal conventions, as well as language and logic. [10]

The Dadaists believed, like the Romantics and the Transcendentalists before them, that humans were inherently “good” beings, and that it was only through a “morally bankrupt” society and culture that this goodness is corrupted and made rotten. [11] Society must then, under these circumstances, be radically altered –and even destroyed– should humanity wish to survive itself. This –the destruction of society through the anti-war and anti-art politic– was the outcome the Dadaists wished to create with their radically transgressive art. The faux definition for the word “Dada” was, according to a popular but potentially false legend, seized upon by a group of people in the Cabaret Café when a paper knife was inserted into a dictionary, pointing randomly to the term “Dada,” a word that once represented in French a children’s word for “hobbyhorse,” which the Dadaists immediately transvalued to signify the “infantile” nihilism and anti-art regression they themselves wanted and represented. [12] Dada was therefore first a state of mind, then an art form –or rather, an anti-art form– seeking to save humanity from a meaningless and decaying immersion in a sullied and banal society. [13]

But how was art’s antithesis, this attack, executed? Marcel Janco, a friend of Dadaist principle founder Tristan Tzara, recalls, “We had lost confidence in our culture. Everything had to be demolished… [and] we began by shocking common sense, public opinion, educations, institutions, museums, good taste, in short, the whole prevailing order.” [14] Dada would thus concern itself with a “shocking” and “bewildering” of its audience to functionalize its attack upon convention, and upon modern rationale, to shock its audience into a reexamination of all aesthetic, societal, and moral values. [15] To do this, they used non-traditional prose, non-sense poetry, found-art, and even music loops. [16] Essentially, the art served to combatant everything rational and traditional –for if reason and logic led people to war, the only route to salvation was to reject logic and embrace anarchy and irrationality, the idea being to shock people somewhere other than where they are. Dada then, in its most condensed definition, served to shock and bewilder, which in the end, became “nothing but an act of sacrilege.” [17] A sacrilege, of course, that is ironically meant to save. However, by 1924, the Dada movement would be so large and inconsistent, that the artists broke off, generally becoming surrealists: a much larger and more expansive movement, though certainly similar to Dada. [18]

Yet by World War II a comparable phenomenon with a similar premise and cause, but a more powerful discipleship, would emerge, principally in Paris. The movement would be called Absurdism: The Theatre of the Absurd. [19] Fostered by Sartre’s proto-Existential work Being and Nothingness, [20] and led primarily by Camus’ The Stranger [21] and The Myth of Sisyphus, [22] Absurdism –a term coined by critic Martin Esslin– [23] was rooted in the avant-garde and nonsense works of Dada, but had a more focused following, and a more singular and better developed message, carried and given force via the phenomenological genius of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. Like Dada before it, it had been another war which would highlight the cruelty, meaninglessness, and alienation of the human race –forcing art and philosophy to answer for it. But while Dada sought to “bewilder and shock” to save human nature, Absurdism sought to bewilder and shock to outline the nature of the human race. The art of the absurdist was not attacking art itself, but simply mimicking what they saw as real life: “The human condition is essentially and ineradicably absurd… this condition can be adequately represented only in works of literature that are themselves absurd.” [24] In a departure from realistic characters, situations, and all accepted convention, Absurdist’s sought to shock people out of their accepted –and false– realities, and force them to see the true nature of both themselves and the world around them. [25]

In the world of absurdism, be it theater, poetry, or prose, the set and plot is darkly surreal –seemingly symbolic– yet holds no meaning or solution to its cryptic code, just as life, to the absurdist, holds no purpose for its being. In these works, time, place and identity are ambiguous and fluid, and even causality often breaks down into bizarre, incoherent –absurd– forms. Meaningless plots, repetitive or inconsequential dialogue and dramatic non-sequiturs are used to create dream or nightmare worlds, and it now can certainly be seen why the movement is relative to David Lynch. It is also shown that everything critics use to attack Lynch –that his art is too “surreal, illogical, plotless, conflictless” – are exactly the forms of narrative an Absurdist strives for. That is not, of course, to say that the Absurdist tries to be as incoherent as possible, without anything to say. It is exactly the opposite. Both Kafka and Camus, both absurdists, wrote very straightforward pieces staged in banal atmospheres, yet, with one or two violent absurdities, filled with social commentary, philosophical progression, and political or self-reflexive critique. And like the films of David Lynch, these works often require a intuitive guidance versus a logical one –though no power seems to be lost in the medium. The popular denotation “Kafkaesque” means exactly this: “mundane yet absurd and surreal circumstances,” [26] and it comes as no surprise that Lynch is an avid fan of Kafka, even drafting a script for Kafka’s seminal work The Metamorphosis. [27] Yet modern critics ignore the nature of this art, holding some sort of pre-art structuralist supposition about how the nature of narrative should be: that it should be easily explained, easily classified. Of course, to an absurdist, such laws are simply absurd.

Unlike Dada, the effects of Surrealism and Absurdism –and especially Existentialism– are still very evident, especially in literature. However, in film, experiments in surrealism and absurdism are somewhat rare, though it could be noticed that some, such as Alejandro Jodorowski, attempted to resurrect surrealist/absurdist values in cinema –perhaps unsuccessfully [28]– though Luis Buñuel has obviously worked in surrealist cinema for decades. It could perhaps be argued that Tarkovsky, Svankmajer, the Quay brothers, and some of Godard were somewhat philosophically surreal or absurd, though not to the extent the former were, as these latter filmmakers were more symbolic or cryptic than purely absurdist. In modern times, some directors such as David Cronenberg, Takashi Miike, Bruno Dumont, Lucile Hadzihalilovic, and a few others, are operating inside radically absurdist or surreal values –though no one seems to execute the same sorts of absurdist dream archetypes as David Lynch, nor works so consistently and passionately with surreal narratives. Lynch is no doubt taking the baton from Buñuel, his trajectory the same lonely and often misunderstood road that Buñuel inhabited, with just as much passion and conviction –and just as much critical distaste. From Eraserhead to Inland Empire, [29] Lynch has continually returned to the absurd, to the bizarre, and to the esoteric in his cinematic attempts, and has continually been misunderstood out of context.

Now that a brief understanding of Dada and Absurdism has been provided, I will take a look at how Dumbland should be understood in light of its artistic context, and argue that it is, in fact, everything the critics say it isn’t: a very relevant, extremely dense –often hilarious– nightmarish satire of the absurd, grotesque side of banal Americana.

An episodic study of the series Dumbland

One of the beautiful things about animation in the hands of a Surrealist, is that animation has no limits, and holds no visual fetters upon the director, in other words, if you can think it, you can draw it. As such, it is almost a better medium for surrealism than that of film because of its seamless ability to violate physics, gravity –or whatever else– without any extra cost or effort. For example, one of the main reasons Lynch has never directed a film version of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis –though he has a script ready and waiting– is because (according to him) of the near impossible task of making and filming a man turn into a beetle in the same matter-of-fact manner that characterized the novella, with the same banal realism. [30] With animation, however, such a task is more than possible. And Dumbland, with its crude nature, makes every ridiculous act totally acceptable within the spaces of the series. In other words, our doubt as an audience is infinitely suspended, because we hold animation to a different standard than film. And for the surrealist, this can be a beautiful thing. There is no doubt that Dumbland could ascend to the heights of any hip cult animation before it, though it doesn’t nearly have the technical appeal of something by, say, Don Hertzfeldt, nor the more subtle satire of Mike Judge –though is easily darker and (in this critic’s opinion) more interesting, as well as far more layered, dense, and esoteric.

And considering the animation of Dumbland –which Lynch drew, voiced, and scored all on his own personal laptop– the first thing that will be obvious to anyone extensively familiar with Lynch’s work is the similarity of art between Dumbland and Lynch’s now defunct comic strip, “The Angriest Dog in the World,” [31] –another experiment in animated absurdity– which was a rather unconventional comic strip that ran on various newspapers between 1983 and 1992, characterized by random non-sequiturs and aphorisms, which some appreciated and others derided as frustrating and frivolous (much like most of Lynch’s art). But both animations have the same black on white crudeness, and both have the same sort of fencing and suburban plotting as a consistent backdrop to frustration. The angry dog who is the main focus of “The Angriest Dog in the World” –who is so angry he stands in a constant state of rigor mortis– has a lot of similarity to Randy, the main character of Dumbland. Both are sectioned off from the rest of the world, and “chained” literally or otherwise to inhabit a small suburban plot, as random, repeating absurdities and banalities drive the two –Randy and the angriest dog– into a state of perpetual rage, violence, and existent immobility. And whether Lynch is operating on complex allegory and microcosm, or simply on personal experience and subconscious self-reflexivity, his work almost demands intense study, for even the absurdism of it all says volumes about the nature of Dumbland –and not the Dumbland series, but Dumbland the real place –be it within Lynch’s mind or America itself.

Episode 1: “The Neighbor”

Each episode on the DVD is announced by a Lynchian assault of sound, in this case, the characteristic electrical buzzing a la Eraserhead which can be found in almost any other Lynch film, followed by a slow panning of Randy –the series’ excuse for a protagonist– who greets us with a perpetual gaping mouth while breathing loudly and orally, a profoundly ugly expression on his apish face. This little intro, complete with Dumbland theme music, which is a sort of proto-punk keyboard preset, always states the episode number, and precedes the episode’s title. The first episode of Dumbland is entitled, “The Neighbor,” and sets the pacing and the artistic climate for the rest of the series, as each episode progressively builds and climaxes both in art –as Lynch seems to perfect his Flash animation skills episode by episode– as well as in plot, leading to a final absurdist onslaught complete with dancing, singing ants and Badalamenti-styled music that will have any Lynch fan squirming with glee.

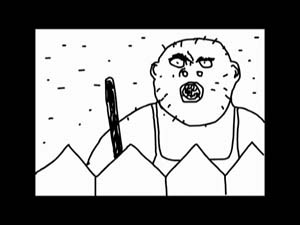

As the series opens, we see a thickly brutish and ugly figure perched rudely over his neighbor’s fence, glaring wide-eyed and wide-mouthed at a wooden shed off in the distance. This fat man is wearing overalls, a white-beater T-shirt, is unshaven, and looks profoundly unattractive –and is our protagonist, Randy. It becomes quickly apparent that Randy, for whatever reason, has decided that he likes the wooden shed in his neighbor’s yard, and no doubt would like to own it himself. Reversing the infamous Frostian line, “Good fences make good neighbors,” [32] a fence in this case seems to both inspire the covetous rage of material possession, and outline the essential alienation of individual families plotted in suburban homes –in other words, Dumbland fences making very bad neighbors. Here we get an initial taste for Randy’s origin of rage. Fenced off from contact and isolated in his yard, Randy, like the angriest dog in the world, seems to be immobilized and vulgarized by his lack of spatial expanse, repetitive captivity (every panel in the comic strip “The Angriest Dog in the World” is exactly identical, and Randy never leaves his home) and by a selfish and absurd longing for owning what is not his –personifying that well-known aphorism “the grass is always greener…” However, in this case the aphorism causes fits of brutish rage…and brutish flatulence.

Recall again the announcement made by Eugene Lonesco: that one drowning in meaninglessness cannot help but to be grotesque, and we here get a pretty defined denotation of the kind of persona Randy possesses. For throughout the entire series Randy does nothing that would defy the definition of “meaningless.” Wandering about his yard, his home, staring stupefied at his television, struck in an incessant rut of repetition, Randy does absolutely nothing of substance, save that of farting, acting violently, drinking alcohol and cursing, which is in of itself a form of repetition. It seems then that in Dumbland it is the banality of it all –the isolation and boredom of suburban nothingness– that has formed the grotesque nature that Randy possesses and projects. As we shall see in later episodes, it is consistently meaningless repetition that causes the fluctuation of stress, violence, and vulgarity. We can thus assume, based on the absurdist claim of Ionesco, that it is the nature of this meaningless repetition that has made Randy the way he is, affecting also his family, as well as anyone else he comes in contact with. Therefore, Randy is driven mad and into violent regression by his repetitive captivity inside a banal plot of space; and here we see that the connection of Dumbland to Dada emerges.

For if it was the nature of the bourgeois society and the moral vacuity of culture that caused the human to degenerate and rot and war with one another in the early 20th century –as is the Dadaists’ perspective, causing them to use their afore mentioned anti-art tactics– then for Lynch it is the banality and the meaningless repetition of modern suburban bourgeois society that has formed the violent and rotted beasts of today: i.e. the Randy’s. And, appropriately, we find Lynch using the same Dadaist tactics of nonsense art and vulgarity –sacrilege??– to reflect and thus attack the rotted society, which, in this case, seems to be a prosaic suburbia. We find the same artistic parallel with the Absurdists as well. Thus the origin of Randy –his nature, and his absurdity– is blamed upon his state of immersion into ??Dumbland, a place of Eraserhead??-esque stress, repetition, and absurd meaninglessness. Enraged at absurdity, Randy’s rage is no less absurd: ??everything is absurd. And, staring down the timid neighbor, who can do nothing but pathetically reply, “I have a false arm,” helplessly tossing it aside, Randy imposes himself as a beast of absurdity, who both acts and causes that said absurdity, for no reason other than the lack of reason itself.

As a helicopter loudly hovers overhead in a mind-numbing, otherworldly roar –a symbol of imperialism, of government superiority, and of Randy and the neighbor’s own miniscule status– Randy can do nothing but shout obscenities and scream violently, pathetic in his vast inability. No less ridiculous is the neighbor himself, who, in his own mundane existence, has taken it upon himself to apprehensively “fuck ducks.” One must wonder what this “duck fucking” neighbor does in the obscurity of his own home, a common Lynch theme that seems to suggest Twin-Peaks??-style that, upon looking over a fence, or under a bush, or through a closet, one might uncover all sorts of bizarre and fetishized behaviors next door, within the hidden underbellies of suburban moral façade, a la ??Blue Velvet??’s severed ear. It also suggests that the same banal circumstances that created Randy also created this timid, “one-armed duck fucker.” A classic and pitifully humorous line –“I am a one armed duck fucker,”– that seems to epitomize the cruelty, absurdity, and self-loathing isolation each character must face in ??Dumbland; a place that renders men vulgar, grotesque beasts and timid, alienated “one-armed duck fuckers.” At least one of them has the wooden shed, and God only knows what’s hiding inside there. And the first episode ends with classic Lynchian theatre curtains, which no doubt would be stark-red, had the series been color.

Episode 2: “The Treadmill”

Dumbland gets increasingly absurd, as well as violent, in the second installment, which opens with Randy taking part in a particularly repetitive stream of behavior, chugging beer and watching football players unremittingly slam heads back and forth, an important connection that ties the violence of Randy’s sport of choice with his own nature. The sudden sound of a treadmill jars him out of his dormant pattern of violent football and gluttonous alcohol consumption, which is of course a rather common “Americana Father” stereotype, this beer and football pastime, and Randy immediately investigates the source of the noise. Appalled and perplexed at the inexplicable presence of this exercising device –the treadmill being again a rather common suburban stereotype– Randy can find no other sensible response but to slap his wife (who we see briefly for the first time) off of the machine and through a wall. It is now apparent that Randy has no problem with beating his wife, as a drunken, bored, and sport-violence-hyped man might. Randy continues to stare dumbfounded at the machine, as his alien-like son (called Sparky on David Lynch’s website) leaps on and flies also through the wall, following closely after his mother. In a rather inane response, Randy steps on the machine, also being propelled by the spinning belt of the treadmill, flying through the wall, only to land outside. Randy stands, and is –again– loudly flatulent.

In a sort of ape-like anger, Randy can find no appropriate behavior other than to attempt to destroy the machine with a hammer, rather than try to investigate its function. Randy seems to only answer perplexing issues with either violence, or with gluttonous vulgarity, a fact that says volumes about how Lynch views these suburban bourgeois. Of course, this attempt at destruction does not work, as Randy is yet again propelled into the yard, landing on the hammer which impales his posterior. Of course, Randy responds by farting out the hammer, finding only afterwards that he has a visitor –a sparkling and effeminate man trying to sell a product that makes homes smell good, appropriately entitled “Smell Gud.” It is interesting to notice that the man is an outsider, and looks far more attractive than any of the suburbanites. True to form, Randy answers with violence, and punches the visitor in the face. In classic and intensely formulaic Absurdism, the man promptly quotes the Gettysburg address, his head dangling on his stretched neck, this act of deformity again displaying the perfect medium that animation is for the genre of Absurdism.

After this, Sparky runs up to Randy, presenting him with two ducks, leaping up and down, holding the apparently dead ducks by the neck. Randy seems to be pleased, and remarks, “Ah, and they said you was stupid,” Lynch fiendishly implying that Randy himself might have taken up that infectious habit of “duck fucking,” which is no surprise, having taken note of Randy’s proclivity to envy the goings on of his neighbor, who we saw in the first episode (this neighbor however not making another appearance). Grandly absurd, and though strangely sensible in the context of the stereotype, Lynch has outlined many themes in this episode: the apparent beauty of those “on the other side,” the proclivity to answer problems with violence or vulgarity, and, of course, the infectious nature of “duck fucking.” We can’t help but to wonder what happened to the timid neighbor next door, and whether or not Randy has taken it upon himself to steal the man’s ducks for his own usage. Somehow –however absurd– we feel the true depravity of Randy’s pathetic existence, an existence drowning in stereotypes and facile confusion, left to violently react, but never solve: and that’s what Dumbland mostly is, a string of violent reactions, without resolution, rendered hopelessly as nothing more than pointless repetition. Is this what life is? We will have to see.

Episode 3: “The Doctor”

The third episode of Dumbland finds Randy staring dumbly out of his living room window, looking as if he has very little to do, completely useless and inactive without some activity to provoke his violence. Never leaving his home, one must wonder if the window, which is outrageously large, taking up much of the entire living room wall, is appealing to Randy at all, and whether he considers leaving his small space, or wishes in futility to do so. After a second, a distant mailman walks past this window, and Randy asks if he has any mail, cursing and giving the mailman the middle finger when the mailman announces that there is none. It is again interesting to notice that the mailman, an obvious outsider, is another one of these bizarre effeminate, “pretty” males, like the man offering Randy the “Smell Gud” product earlier in the series. After cursing the mailman, Randy turns to notice a broken lamp on the floor. Immediately enraged, he screams, “Who broke the fucking lamp!” A timid, shell-shocked wife, perpetually shaking, frazzled, whimpering, and scampering about, appears, and stutters “I-I-I did.” After this shaky confession she runs off through the house panting, leaping off-screen through what sounds like a dog’s door flap. The mother of this three-piece family, her behavior seems to both suggest that she is hesitantly loyal and honest to Randy in traditional subjection, though constantly horrified and in dread of his perpetual beatings and violence. The fact that she uses a dog’s flap more than suggests her place in the family’s chaste system, and her animated state –relentlessly hysterical, shaking, hair-standing-on-ends– says much about her vast and expected history of abuse.

“I’ll fix it my-fucking-self,” says Randy after his wife has scampered out of sight, the woman leaping frantically through the dog flap. Staring at the broken lamp, a strange stupefaction seems to swell in Randy, and then a thought. Randy holds out his finger, slowly moving towards the exposed wires of the broken lamp. What first seems like dumb curiosity may in fact be much more. For the same brutish Randy who spends his time staring out of his ridiculously large living room window, perhaps wanting out, considering more than his violent banality, is now staring deep into a potential cause of death. Moving his finger closer, then away, then closer to the exposed wires, Randy seems to be deliberating between something. Is it pure stupid curiosity, or perhaps a suicide wish? One is tempted to think the latter. For we have already surmised that Randy is drowning in meaninglessness, made grotesque by his own lack of substance. Would not suicide be both the necessary permission of activity to propel Randy out of this absurd existence, as well as a simultaneous epitomizing of Randy’s own grotesque, violent, self-destroying ennui? This dialectic act is perhaps the first action Randy has taken against himself –a numb performance of self-mutilation, of self-harm. Perhaps Randy does not only expel his violent state on others, but also internalizes it, making Randy a being of unlimited violence: to himself, and to others. The act is absurd, though bizarrely, it is absurdly necessary.

Finally Randy slams his finger into the web of wires, and a strobing, blaring electrocution follows. After a barrage of sound and stark, flashing visuals –Randy paralyzed by a current of rushing electricity– Randy ends up a lump of steaming black ash, cartoon-style, but is not dead. A fade-out suggests a passing of time, and we see an ambulance pull up to Randy’s home. A skinny, mustached doctor is met by the hysterical wife, the screaming wife scampering off out of sight again, while the doctor walks into the home to announce plainly, “I am the doctor.” The doctor, sitting opposite a semi-conscious Randy, performs a few routine procedures, checking Randy’s mouth and heartbeat. Suddenly, however, the doctor turns sadistic, sticking Randy’s finger with a needle while turning and twisting it about, slamming Randy over the head with a hammer, and then jamming a knife into the side of Randy’s face. After every act the doctor asks timidly, “Does that hurt you?” Randy replying, “No,” after all of them.

In more than one way it is implied that Randy is not just morally or metaphysically numb, but actually numb to any sort of real physical pain. When Randy suddenly realizes that a knife is jutting out of his face, the realization is not because of the physical pain that the knife has caused him, but because of the doctor’s act against him, or simply because the doctor is in his house in the first place. There are no nerves and is no brain that the knife has impaled while jutting out of Randy’s face: he has no organs to harm, and thus cannot, perhaps, die, living endlessly then in his violent state. After Randy’s realization –in a scene very similar to the violent/sadistic attack of Dorothy Vallens by a disenchanted Jeffrey Beaumont in Blue Velvet– a loud, frightening organ sounds while Randy grabs the doctor, rings and stretches his neck, slams his head to a bloody pulp on a wall (a la Sailor Ripley and Bobby Ray Lemon in Wild at Heart [33]), throws the doctor to the ground –only then to stamp on his stretched, limp body repeatedly, while the organ sounds in a Badalamenti-like frenzy.

After this sudden and rabid violence, the doctor looks up to Randy to remark, “Just what I thought. You are completely normal.” The doctor, announcing that the endless numbness Randy feels is normal, as well as his hyper proclivity for sudden outbursts of irrational violence, causes Randy’s wife to scream hopelessly, ending the episode as Lynch zooms in on her desperate face. Perhaps the most avant-garde of the series, this episode reflects the nature and characteristics of the Absurdist Theatre: reflected especially by the bizarre and violent mannerisms of the doctor. Though the actions presented are absurd and unrealistic, they do say a lot about the kind of person Randy is –a numb, literally brainless beast who operates infinitely in his own violence and lack of successful self-destruction. It must also be realized that this doctor was perhaps the wife’s last hope to escape Randy, though when Randy was declared “normal,” she is suddenly without hope, destined to be victim to Randy’s “normal” behavior. Not only then have we seen the beast-like mannerisms of Randy in a banality-induced stupor, we have also seen that this sort of absurd persona is, according to medical officials, completely normal. The scream at the end of the episode, then, is supremely appropriate: that it is not just Randy who has fallen victim, but all of society –the doctor included.

Suicide also seems to be the first impulse for a human who has realized his own absurdity –a problem that forced Camus to functionalize his work The Myth of Sisyphus. [34] Like Randy, the Greek character Sisyphus is forced to endure unending repetition, banished to a mountain where he must push a boulder up a hill forever. To Camus, this is an absurdist hero. To Lynch, however, there is nothing heroic in this absurd repetition, only the responses of vulgarity, violence, and perhaps suicide. While Camus praised Sisyphus for enduring the repetition, Lynch might surmise that not committing suicide is itself absurd –a paradox that I don’t really have time to cover in this analysis. However, all of this absurdity, this never ending repetition, as the doctor so casually stated, is “completely normal.”

Episode 4: “A Friend Visits”

In episode four, Lynch opens with the wife quietly hanging clothes on a clothesline. Randy charges from the other end of the yard, screaming obscenities, while the wife drops her clothes and holds up her arms in panic. Randy grabs the clothesline and tries to destroy it, concerned that the clothes line could “slice his fucking head off” when he comes out at night in the yard to “take a shit.” The wife continues to scream, and Randy snatches her face and squeezes, letting go to reveal that he has squashed her face to a tiny pulp, her screams now muted, this smashing making her look a lot like the head-swapped Henry in Eraserhead, whose head and neck was dismembered by a smaller head pushing out from the inside of his body. After the wife’s face is squeezed to a tiny pulp, it suddenly gives metamorphosis to a beautiful woman’s face, which says in a sultry voice, “Say what?” Lynch seems to be insinuating that in Dumbland brutish men can mutilate women with abuse and violence into “beautiful” women –an allusion to, among other things, the rampant plastic surgery of suburbanites and the nature of female molding/objectification, as well as the idea that “wife beating” could somehow reform a woman. After the wife’s metamorphosis, Randy continues to tear up the clothesline, throwing it into the street and causing a car accident to occur.

After this chaos, Lynch cuts to Randy and an unnamed Cowboy sitting on stools while having a chat. This conversation resembles very much the mannerisms and tones of the Texans in Wild at Heart –minus the obese, nude women dancing in the street– the Cowboy resembling very much the elusive, albino cowboy in Mulholland Drive [35]. After chuckling for a moment and engaging in some flatulence, the men begin to converse about the many joys of killing, gutting, ripping, and decapitating several animals, including sheep, deer, and fish. The cowboy is holding a beer, and spits after every sentence, rivaling the vulgarity of even Randy. It is revealed that both men find “killing things” to be of great joy, and enjoy hanging decapitated heads on their walls, laughing at each others stories of hunt and dismemberment.

This Cowboy is the first individual who Randy is docile around, ostensibly because the Cowboy is capable of a greater violence than Randy, which Randy dumbly admires, staring at the Cowboy in a sort of reverent stupefaction. They both seem to have a lot in common, both drinking beer, engaging in violent sports, sharing flatulence, both enamored with the thrills of killing and gore. Many obvious “redneck” backwoods stereotypes have been cycled through here: the traditional inferiority of the wife, the joy of hunting and trophy killing, the love of beer and sports, the humor of vulgar behavior, and the relishing of barbaric, primitive lifestyles; and Lynch seems to absurdly demonstrate the truly depraved nature of these men, wherever they are. Lynch ends the episode with a bemused Randy slowly stating, “I like to kill things,” which he certainly does, be it his wife, a treadmill, or a clothesline.

To Lynch, the violence of sports and hunting are not separate joys isolated from everyday life, but actions that both reveal the true nature of a man, and bleed into his regular life, associating themselves with everything the man does. Both men seem to long for the primitive, animalistic times where they could roam and hunt and gore freely, which accounts for the awkwardness of a Cowboy sitting in the fenced backyard of a suburban neighborhood. Aware of their own boredom, it is vulgarity and depravity that seem to them to be saving forces, to free their repressed notions of male superiority and animal dominance. Lynch, no stranger to Freud with his detail of the Oedipal complex in Blue Velvet, and dream wish fulfillment in Mulholland Drive, again takes a Freudian look at man, showing the repressed, animal lusts of Randy made docile by the nature of an enveloping society. And now we have a double conflict: the banal meaningless of a mundane society, and the inner urges of a man wanting to kill. And whether it was society that made man this way, or man who made society because he was this way, a debate that has been going on for some time now, the end result is the same. But, of course, though we see hints of both Dadaist and Freudian outlooks, the final perspective is again nothing short of Absurdist. In other words, perhaps while Sisyphus was pushing that boulder up the hill, he took a break to fart and dismember some poor creature for some relaxation and libido expression.

Episode 5: “Get the Stick”

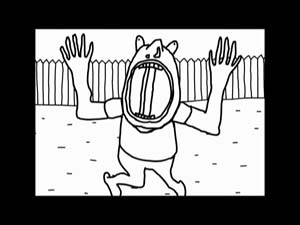

The most violent installment of the series, this episode details the events after a man with a stick wedging his mouth open bursts into Randy’s yard, frantically writhing in futility to dislodge the stick from inside his mouth. As the alien-like son Sparky yells “Get the stick! Get the stick!” Randy attempts, simply, to get the stick. However, instead of simply cutting the stick in half, Randy tries to pull it free, eventually breaking the unfortunate man’s neck, impaling both of his eyes, and finally turning him into a pulpy mess of waddling flesh after yanking the stick out from his throat. An absurd sequence of events that could only really be done in animation, this episode seems to show yet again that Randy answers all perplexing situations with brute violence. One must wonder, of course, given Randy’s conversation with the Cowboy in the previous episode, whether or not he did in fact enjoy this act of “accidental” violence.

Thoroughly absurd, and containing a lot of Dadaist repetition, Lynch never cares to show how the stick got there in the first place, but simply shows that should some problem arise, it will not be answered with a carefully and patiently thought out solution, but with aggravated force and aggression –even revenge. This allegory could be applied to many things, be it politics, war, or simply individual procedure, though Lynch seems to surmise it is how one would find a solution in Dumbland. After “solving” the problem, Randy stares after the man, holding the dislodged, bloody stick, only to remark in an annoyed voice, “Fucker never even said ‘thank you.’” Blackly humorous, the episode is yet again a tribute to the nature of Randy, and whoever it is that Randy represents, made strangely relevant in these times. One could imagine, for instance, a violent Bush administration tearing up Iraq and bombing it to a pulp, leaving the country war-torn and demolished, only to be angered that the “fucker never even said thank you.” But of course, that is another essay.

Episode 6: “My Teeth are Bleeding”

The most layered and Dadaist of all the episodes, episode six of Dumbland opens with a shot of Randy’s living room, which each member of the family sitting together in the same room, though all engaging in very separate activities. Lynch very successfully makes usage of layered sound in this episode, creating a chaotic barrage of audio activity accurately displaying the disarray and disconnection of a family seemingly together. A very blatant and stark portrayal of the American family broken and severed into niches via technology, this scene serves to demonstrate the normality of complete chaos, and of faux togetherness. All in their own plane of operation, Randy is watching loud wrestling on the TV, Sparky is noisily jumping on a trampoline, and the wife is sitting and doing her characteristic acts of hysteria –all while crime, war, and traffic rages outside the family’s large window, perpetually unnoticed. Perhaps a display of post-modern isolation and ennui, each family member seems to be so consumed with themselves and their activity that all the chaos and disorder happening around them go totally unnoticed. Even when Sparky’s teeth begin to bleed, and the wife begins to inexplicably gurgle blood –her tongue whipping around windmill style– nothing is done. It is only until a fly buzzes in front of Randy’s face that he becomes upset, swatting at it and yelling “Fucking flies.” A perfect illustration of self-consumed ignorance, and the ability to filter out realities while consumed with another, Lynch adds another (post-modern) dimension to his skewing of this place called Dumbland.

Episode 7: “Uncle Bob”

To add more dimension to the wife’s obvious hysteria, Lynch presents us with her mother-in-law: a butch, large, vulgar woman who refers to her daughter as “bitch” and who keeps Randy scared and silent qua threats of violent castration. Announcing that she is taking her daughter shopping, the mother-in-law commands Randy and his son to keep watch over uncle Bob while they are gone. Uncle Bob stands shaking in the corner, breathing rapidly, looking very much like the old man who stamps his foot and snaps his fingers at a distant Laura Dern in Wild at Heart. After the mother-in-law and the wife leave, Randy and Sparky stare perplexed and fearful at the esoteric, ostensibly sick old man. Right away, it is apparent that something is very wrong with the old uncle.

In Dadaist tradition, Uncle Bob begins to cycle through repeating patterns of: punching himself in the face, stamping on the floor, making strange oral noises, farting, vomiting, and then finally punching Randy in the face. Awe-struck and confused, Randy and Sparky cannot help but to stare at the bizarre uncle. With all the absurd repetition –a repetition that seems to resemble sickness and a slow death– Randy finally punches Uncle Bob back. “I heard that!” screams the mother-in-law, who charges Randy, in turn punching him. Again a journey into Abstract Theatre, this episode shows the absurdity of death and sickness, and the violence residing in any family structure. Also, of course, we again see that it is repetition that provokes all violence and horror.

After a cut to black, we find rather humorously that Randy has hidden in a tree, waiting for the mother-in-law and the uncle to leave his home. Randy is thus rendered weak and childish when controlled by a mother-figure, though one can imagine that in the absence of the mother-figure, Randy is again puerile and viciously barbaric. Sparky informs Randy that the mother-in-law and the wife had to take Bob to the hospital because he has “bit his foot off.” Another humorously absurd plot device, Uncle Bob seems also to be in need of desperate self-end, much like Randy. For we have noted earlier that Randy is caught in cycles of mundane repetition, drowning in banality and meaninglessness, and we can easily surmise that Uncle Bob is no different, forced into patterns of vulgarity and self-destruction by his own repeating sickness. We have also seen, however, that the doctors of Dumbland consider this state to be the normal manner of existence, which is probably what the doctor will say when the mother-in-law and the wife arrive with a one-footed-uncle Bob. The medical officials will no doubt announce that eating off your foot is “Completely normal.”

Episode 8: “Ants”

In the final and most Lynchian of the eight episodes, we find Randy suddenly perplexed by an onslaught of ants in his home. Acting in typical Randy fashion, he grabs a can of ant pesticide called “KILL” out of his cupboard, and hunches down over the ants, ready to spray. Randy hesitates before spraying, however, and we are meant to notice that the spray can is pointed towards Randy’s face. Similar to the broken lamp sequence in episode three, where Randy touches the exposed wiring of a busted lamp, Randy seems to deliberate between whether or not he should spray himself. Again, we are reminded of Randy’s strange urge to harm himself –if not commit suicide– and Randy is no doubt curious as to whether or not this can of KILL could in fact kill him. Not surprisingly, he sprays the pesticide into his face, and screams in pain.

Randy begins to hallucinate after breathing the pesticide, and is met with dancing ants on a stage singing to Badalamenti-styled music. No denotation can be used to describe the sequence other than “Lynchian.” The ants begin to mock Randy, calling him an “asshole,” a “shit face,” and a “dumb turd.” The ants grow in number, and Randy cannot help but watch as they ridicule him. What can only be a sort of self-realization, Randy, in his own hallucination, has realized that he is nothing less than a shit-faced, dumb-turd asshole. And one cannot really argue with the allocation. However, instead of giving this realization some sort of solution, Randy simply awakes from his hallucinatory state enraged and feral, trying to kill all of the ants with his hands. In his frenzy, he climbs a wall, slapping at the ants, only to fall, snapping his neck and falling over backwards.

In the final sequence of Dumbland, Lynch gives us a microcosm for all of Randy’s life: Randy is stuck in a full body cast, immobile, screaming as a trail of ants enter and crawl across his body, just as Randy is stuck in his suburban banality, unable to leave or function, left only to scream and rage as an unending torrent of annoyances creep into his life without solution, meaning, or end. Blame the cast, blame the ants, or blame Randy, it doesn’t really matter. The same absurdity will not desist.

A Final Conclusion:

After exhausting the nature of Randy, one must only ask: who does Randy represent? Or, perhaps more appropriately, where is Dumbland? Is it America? Is it inside every human? Is it the human condition? Nevertheless, Lynch has, via Absurdist and Dada musings, stimulated thought on the inherent nature of people, of society, and of America. We can all recognize the stereotypes in Dumbland –and perhaps that is not a good thing. For if we resemble this place that Lynch has created, we are certainly in dire circumstance. But we must ask: is human life merely an illogical, inescapable body-cast plagued by never-ending torrents of ants? Perhaps it is just that absurd. But like the Dadaist, Lynch sees society (or perhaps life in general) as a place of banality, of meaninglessness and repetition, forcing vulgarity and violence to surface from the human body. And like Freud, Lynch recognizes the violent lusts and animalism lurking beneath every suburban façade, launched by the nature of this repressing banality. And like Camus, Lynch finds the nature of Randy’s world to be absurd, without meaning, and without solution –where indifference and ennui cannot help but to dominate. Perhaps there is a solution, like the tongue-in-cheek happy robins in Blue Velvet, though Lynch has never really been one for happy endings.

However, if anything is certain, it is that those who wish to simply attack Dumbland, without realizing the relevance of its satire, nor the conviction of its absurdism, nor the necessity of its mockery, are much like Randy ignoring the truth of the ants, only wanting to attack and kill and ignore. In other words, if David Lynch’s Dumbland bothers you –as it did many– be very careful that you are not its subject matter.

Finally we are forced to cram all of the many philosophical and sociological implications of Dumbland into a single, encompassing philosophy: the Philosophy of Dumbland. For we have, with these eight episodes, a sort of map for the depraved human, for the dysfunctional family. We also have a map for the cause, and the end. What is this Philosophy of Dumbland? We find a family, forced into banal repetition, their lives hopelessly absurd, altered only by occasional outbursts of violence, vulgarity, and suicide, left to slowly die in repeating patterns of non-reason, and illogical existence. Now we must ask: is this über-cynicism accurate? What is a human? A human is, then, according to this Lynchian map, a being of repetition, who eats, shits, sleeps, procreates, hunts, etc., all in repeating patterns of meaningless cycle, changed only by the occasional libido joys of violence and fetishized sex, though forced to realize his or her own depravity, and thus required to morally answer for these said “depraved acts” qua suicide. Unprecedented in its pessimism (and perhaps even nihilism), we find that Dumbland may not be the stupid little melodrama we thought it was, but much, much more. We are reminded of that lingering image of a man helpless in his full-body cast, left to scream helplessly as a torrent of ants derail his rest. Is this the allegory of the human condition?

We started this analysis with a contextual study of Dada and Absurdism, leading up to a textual journey into Dumbland. Now we can see that, once put in context, Lynch seems to be picking up where the Absurdists left off: with Sisyphus. Lynch has merely modified Camus’ infamous allegory. For instead of a hero pushing up the boulder (that is life) up the hill (that is absurdity), we have Randy. And this time, the setting for this theory is not a post-war France, but a place that makes banality and mundane repetition, as well as hidden fetishized underbellies beneath moral façade, much more apparent: suburban America. But instead of merely pushing a rock up a hill for all of time, Sisyphus has got other concerns to aggravate him –such as dancing ants who, while singing, repeatedly refer to the ever diligent and ever absurd Sisyphus as a “shit face,” an “asshole,” and a “dumb turd.” Thus, in context, Lynch has, deliberately or otherwise, functionalized a new, modified Absurdism, far more pessimistic and far more hopeless than any of his predecessors, though rather appropriate and unsurprising, in light of Lynch’s cynically dark and comically hopeless oeuvre.

Endnotes

1 Dumbland (David Lynch, USA, 2002).

2 The Grandmother (David Lynch, USA, 1970); Eraserhead (David Lynch, USA, 1976); Blue Velvet (David Lynch, USA, 1986); Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (David Lynch, USA, 1992).

3 Kill Bill (Quentin Tarantino, USA, 2003); Jackie Brown (Quentin Tarantino, USA, 1997); The Black Dahlia (Brian de Palma, USA, 2006) Me and You and Everyone We Know (Miranda July, USA, 2005).

4 Internet Citation: Bohemian Ink: Absurdism.

5 Internet Citation: Lynch’s own words, though I feel he was talking of the place, not so much the series. Lynch was, no doubt, being coy. Lynch Net.

6 Internet Citation: David Lynch.

7 Internet Citation: Information on Dadaism. Secondary source: Wikipedia.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

fn11.Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Internet Citation: Wikipedia.

15 Internet Citation: Information on Dadaism.

16 Internet Citation: Wikipedia.

fn17.Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Internet Citation: Bohemian Ink: Absurdism.

20 Being and Nothingness. An Essay on Phenomenological Ontology By Jean-Paul Sartre. Translated and with an introduction by Hazel E. Barnes. New York: Philosophical Library, 1956. 638 pp.

21 The Stranger. By Albert Camus. Trans. Matthew Ward. New York: Knopf, 1988.

22 The Myth of Sisyphus. By Albert Camus. Vintage Books, New York, 1991.

23 Internet Citation: Absurdism – Wikipedia.

24 Internet Citation: Bohemian Ink: Absurdism.

25 Ibid.

26 Internet Citation: Wikipedia – Franz Kafka.

27 Internet Citation:Wikipedia – David Lynch.

28 See El Topo (Alejandro Jodorowsky, Mexico, 1970) and The Holy Mountain (Alejandro Jodorowsky, Mexico/USA, 1973).

29 Eraserhead (David Lynch, USA, 1976); Inland Empire (David Lynch, USA/Poland, 2006).

30 Internet Citation: Wikipedia – David Lynch.

31 Internet Citation: Wikipedia – “The Angriest Dog in the World”.

32 Internet Citation: See the Robert Frost poem, “Mending Wall”.

33 Wild at Heart (David Lynch, USA, 1990).

34 Internet Citation: Wikipedia – The Myth of Sisyphus.

35 Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, USA, 2000).