The Sister of Ursula & the Terza Visione

PS: This analysis of the film/DVD contains spoilers.

In his excellent essay “A forkful of westerns: industry, audiences and the Italian western,” Christopher Wagstaff defines the particularities of the Italian film industry during the heyday of popular genre in Italy: the 1960s, and 1970s. During this period Italian theatres were broken down into the prima visione, seconda visione and terza visione (first, second and third run). The A pictures in Italy played in the prima visione (first run) which meant a larger number of prints playing in the best theatres across the major cities. The seconda and terza visione played in less prestigious theatres in major cities, or theatres in less populated areas, with lower ticket prices, and (usually) with much longer playing runs than in the prima visione. Wagstaff notes that the terza visione audience was more like a television audience, going to the theatre after dinner, without any particular film in mind, arriving without respect to start time, and often using the outing as a social event, to talk during the screening, meet with friends, etc. Whereas the audiences for the prima visione were middle-class, and, generally speaking, more sophisticated in terms of selecting a particular film, the terza visione audience went out to go to a theatre (253). The viewing culture also reflected the films that screened in these theatres, with the more formulaic and popular films playing at the second and terza visione. The popular filone (though there is no direct English translation, genre comes closest), such as peplum, mondo, spaghetti western, giallo, comedy, poliziesco (crime), and horror are the sort of films that played at the terza visione, films which relied on more of an exploitation angle (sex, violence, sensationalist subject matter) to draw in their spectators. Wagstaff describes the type of emotions that were normally elicited in the more successful films at the terza visione as follows: “The peaks in the electrocardiogram of the terza visione viewer’s attention and gratification were supplied by the three ‘physiological’ responses (sex, laughter, thrill/suspense) that were interchangeable as plot lines, and that a cinema would dose according to the cultural expectations of its audience: in the south, comedies were more common that erotic films” (254).

Hence films that played in the terza visione understood that to gain the full attention of their audience often required scenes that stimulated these psychological responses. The best way to get the attention of a person on a full stomach with a few glasses of wine in them, chatting with his or her friend, was to show a woman undressing, or a knife penetrating a body. In the giallo this meant that violence, sex, nudity (mainly female), and perversion of all colors (sexual, psychological) became staples. Hence if a woman was to be victimized, the director would be sure to include a scene of her undressing, showering, and readying for bed before she was killed. A little sexual titillation before murder went a long way. For many North American viewers these scenes of women undressing appear gratuitous, and in some cases misogynist, but they are merely mechanisms to regain (or ensure) an audience’s attention. Of course not everyone attending these films were men, but Laura Mulvey’s reading of the ‘visual pleasures’ of classical Hollywood cinema being geared toward a patriarchal, male gaze is in evidence here. Which does not mean that certain enterprising directors did not take advantage of this ideological nature of terza visione spectatorship and challenge, question or subvert these very same mechanisms and the emotional pleasures involved.

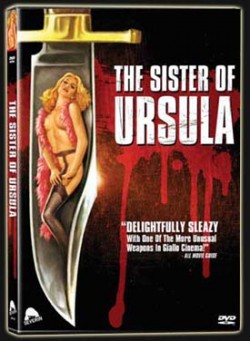

The Sister of Ursula is one of the most transparent terza visione films on offer, a textbook recipe in such mechanisms, but with an irony that suggests a certain reflexive awareness of the conditions. As the pull quote states on the cover of the Severin DVD box, “Delightfully sleazy. With one of the more unusual weapons in giallo cinema.” The later point –unusual weapons– reflects a play on words which brings to the forefront the prime values of sex and violence to the terza visione. The killer’s ‘weapon’ in question is not the archetypical knife, or a rope, or chainsaw, but a penis of huge proportion. Although the said weapon is revealed at the end to be a large penis-shaped medieval wooden sculpture, the die has been cast. The murder weapon actually makes an innocuous introduction ten minutes into the film, seen on the night table in the hotel room of the two central characters, sisters Ursula (Barbara Magnolfi) and Dagmar’s (Stefania D’Amario). Hence it is a clue to the killer’s identity, though impossible to know at this point in the film.

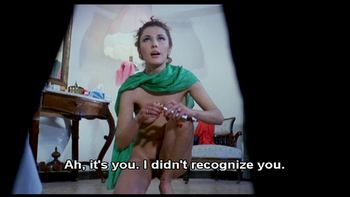

Barbara Magnolfi (who appeared in Argento’s Suspiria as one of the hissing ballet students) and Dagmar Beyne (Stefania D’Amario, pictured above, who also appeared in Lucio Fulci’s Zombie, Gates of Hell, and the nunsploitation flick Behind Convent Walls) star as two Austrian sisters, Ursula and Dagmar Beyne, who travel to a beautiful seaside Mediterranean vacation resort to get over the recent suicidal death of their father. While Dagmar seems hell bent on a relaxing vacation with the possibility of romance, Ursula is a neurotic mess. Not only does she suffer from religious delusion but experiences traumatic violent visions which may be either from her past, or prophecies of the future. Once in their hotel room Dagmar strips in front of her sister, in a purely exploitative moment meant for the sheer titillation of her amazingly lithe body. Director and writer Enzo Milioni ‘aestheticizes’ the proceedings with his harmonious mise en scene, with the beautiful clear blue color of the Mediterranean sea invoked by the blue interior colors of their hotel room, the hotel veranda, and the deep blue sky.

The owner of the hotel nightclub is a suave middle-aged man named Roberto (Vanni Materassi). In the first nightclub scene we are introduced to the blonde performer, Stella Shining (Yvonne Harlow), and a young stud, Filippo/Gianni Nardi (Marc Porel), Stella’s drug addicted former lover. Roberto’s estranged wife Vanessa wants to divorce him in favor of her new flavor of the month, a female lover, but Roberto, who has designs on Stella, fears that losing Vanessa (who is the couple’s main source of income) would also mean losing the hotel which, based on how sparsely populated the nightclub was, is doing poor business.

The first murder scene begins as a soft-core sex scene. A prostitute picks up a client with a preference for voyeurism, so to appease his fetish she calls on a lover and the client watches them make love secretly (for the man) through a peephole. The sex scene goes on for several minutes, including implied oral sex and intercourse. The sex is intercut with close-ups of the ‘watcher’s’ eyes, framed as if peering from behind a hole or mask. This inclusion of the killer’s ‘third’ gaze (in addition to the viewer’s and the camera’s) that prefers to secretly watch the lovemaking before killing one (or both) of the lovers becomes an important motif that is cleverly punctuated in the scene where the killer’s identity is revealed. After sex the prostitute tells her lover to leave, at which point her client enters the room from behind a curtain. The scene assumes the killer’s POV, framing the woman’s shocked expression as she looks in the direction of his groin. The romantic music gives way to a frenetic, agitated ??Halloween??-esque score. The shot cuts to what looks like the shadow of a huge erect penis cast onto the room’s television screen. The black-gloved killer knocks the prostitute onto the bed, then attacks and suffocates her. The scene cuts to a brief close-up of the killer’s (?) disfigured face (an image which is never shown again or explained). A clever sound edit on a woman’s scream shifts the location back to Ursula in her hotel room, waking up from a terrible nightmare. Did she ‘see’ the murder? Or was it just a bad dream?

The next murder occurs about twenty minutes later, with the same set-up: a protracted soft-core sex scene between a young vacationing couple stopping for a sexual liaison in a castle. Like the first sex scene/murder there is a person watching the lovers –we get the same close-ups of the voyeuristic eyes– only now the people involved are unaware of the gaze. The killer murders the young man with a knife, but reserves the woman’s death to a more misogynist and sexually provocative method: death by his huge member. The murder of Vanessa’s lover Jenny is edited in the same way as the first death of the prostitute, with Jenny accepting money to arrange her lesbian lovemaking for the voyeuristic gaze of the unidentified paying customer, who in turn murders Jenny after Vanessa leaves the bedroom. The murder occurs off-screen, but when her body is discovered by Roberto (who had intended to pay her off to leave his wife) the splattered blood around her groin area indicates the sexual (misogynist) nature of the attack (Stella’s murdered corpse is later discovered in a similar state, laying on the floor of her bedroom).

At the seventy-five minute mark a doctor discusses Ursula’s psychological state with Dagmar. We learn that the suicidal death of their father may have triggered Ursula’s telepathic/psychic powers as a defense mechanism against the trauma. Dagmar claims that the circumstances behind their father’s suicide –their mother leaving him for another man– was withheld from her, but that Ursula somehow still seemed to understand what had happened (her psychic powers?). It also provides a clue to the identity of the killer, which is revealed a few minutes before the end when Dagmar sees Ursula standing in her room dressed like their father, wearing black from head to foot. Taking a cue from Psycho, the twist is that Ursula suffers from a split identity, imagining herself to be her father, and Dagmar his wife (their mother) Martha. The murder weapon is revealed to be a gift that Martha gave her husband as a final gesture of contempt before she left him. The scene provides a psychological justification for the murders: Ursula has internalized her father’s pain (which led to his suicide) over his wife’s infidelities and enacts vengeance by ‘killing’ all of her wife’s imagined lovers, before attempting to kill Martha, who she continually refers to as a ‘whore.’ Director Milioni even interjects a possible reference to Peeping Tom when Ursula says, “I saw terror in the other women’s eyes too, before I killed them with this” (the phallic wood sculpture she holds in her hand). Filippi hears Dagmar’s screams and comes to her rescue; after a brief scuffle, Ursula backs away from Filippi, yelling “don’t touch me, don’t touch me,” and accidentally falls out of an open window to her death.

What is odd about this final scene is that we still get the coded intercuts to the voyeuristic ‘third gaze’ eyes, but in this scene they can not be assigned to any point of view in the narrative space, as they were in the previous murder scenes (where the killer, Ursula, was hiding somewhere in the narrative space, looking at the lovemaking). In this case there is no ‘watcher’ observing the lovers. Which suggests that by leaving in this unassigned point of view, director/writer Enzo Milioni is making a reflexive commentary on horror/thriller spectatorship –aren’t we also watching without being seen? (Which would also give some credence to the Peeping Tom allusion.)

With every murder (the prostitute, the tourists, Jenny, Stella) the victims die immediately after sex (Stella dying a few scenes after having had sex with Roberto), which foreshadows the stalker film convention which connected promiscuity with victimization. Only in this case, like the phallic murder weapon, the connection between female sexual expression (of any kind) and violent death has the stench of a misogynist morality to it.

The Sister of Ursula earns its designation as being ‘sleazy’ largely because the number of sex scenes outnumber the murders, and director Milioni places more screen time on sex (or erotic) scenes which have nothing to do with advancing the plot (which the sex scenes leading to the murders do nominally). An example is the ludicrous scene where Dagmar masturbates with a gold chain while lying in bed next to her sleeping sister (complete with breezy porn style music). Milioni makes sure to include a broad range of sex scenes: straight sex, lesbian sex, and female masturbation, with both male and female full frontal nudity. On top of the outright sex scenes, there are many scenes where a woman simply undresses for the camera, like the scene leading to the lesbian encounter between Vanessa and her new lover Jenny (Antiniska Nemour). While waiting for Vanessa, Jenny undresses in front of a mirror, joyfully dancing to music playing in her room while applying perfume. With no one in the room, her nudity plays directly to the viewer’s gaze, one which in the initial terza visione setting would have been predominantly male.

Like most gialli, there is always something of interest on hand, whether it be stylistic flourishes, music, or general mise en scene. In this case the music by Mimi Uva is particularly engaging for how it alternates between languid, forgettable muzak for the sex scenes, and more offbeat, abstract music for the exposition and murder moments.

Though not a classic giallo by any means, Eurohorror and Eurocult fans will be happy that Severin has made this unique film available in such an excellent transfer. The 16×9 anamorphic, 1.85 transfer showcases the lovely coastal, mountain-side location, including many picturesque wide shots of the hotel’s cliffside vantage. The print source is strong, with good color and contrast and little dirt or scratches in evidence. Also a plus is the choice of Italian language with English subtitles. Along with a trailer, the main featurette is a 30 minute piece entitled “Father of Ursula,” an interview with writer/director Milioni. The film’s terza visione heritage is confirmed by Milioni’s statement that the film played for three months at the Tiffany theatre in Rome. The Tiffany Cine was built as an adult cinema in the 1970s, and closed in around 2003-2004. [1] Milioni also identifies the prop that served as the film’s phallic weapon as a 17th century Magellano sculpture of a monk, which he proudly holds up to the camera. The irony of selecting a valued art object as such a vile murder weapon is not lost on this viewer!

Endnotes

Bibliography

Christopher Wagstaff. “A forkful of westerns: industry, audiences and the Italian western,” Popular European Cinema. Eds. Richard Dyer & Ginette Vincendeau. London, New York: Routledge, 1992, 245-261