Science Fiction Soviet Style

As part of its ongoing mandate to unearth the past as well as the future of fantastic cinema, Fantasia 2007 programmed a wonderful retrospective of Russian Science Fiction cinema which included Cosmic Voyage (1936, Vasili Zhuravlev), Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1979), Planet of the Storms (1961, Pavel Klushantsev), To the Stars by Hard Ways (Richard Viktorov, 1985/2001 is 20 minute reedit), Amphibian Man (1962, Vladimir Chebotaryov, Gennadi Kazansky) and Zero City (1988, Karen Shakhnazarov). All of these films are part of a larger initiative organized by Seagull Films called “From the Tsars to the Stars: A Journey Through Russian Fantastik Cinema,” a series of 16 films programmed by New York based Ally Verlotsky, which has been touring North America since 2006. The Fantasia programmers met Verlotsky last year when they invited her to introduce Viy, featured at last year’s Fantasia. The screening of a few Russian fantasy films last year snowballed into this year’s major retrospective, which was made even more lip smacking by the fact that many of the films were screened in new 35mm prints. My survey of these films will include one film in the series which ended up not showing at Fantasia, First on the Moon (2005 Alexei Fedorchenko).

By far the best and most famous of the films in this series is Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker. If there is one film that a fan of Russian or science fiction cinema will have heard of it is Stalker, based on the classic science-fiction novel by the Strugatsky brothers (Boris and Arkadi), Roadside Picnic. In the film a trio of men, comprising the titular Stalker, a Professor and a Writer, travel into a mysterious, sanctioned area called the Zone, where, according to legend, there is a wish fulfilling room. However, we learn that you enter at your own risk, since the room fulfills your deepest inner wish, which is not necessarily what you may think your deepest inner wish is (how well do you know yourself?). Whereas the novel makes it clear that the Zone is a result of alien visitation, the film leaves open other possibilities (divine intervention? Government experiment?). In the novel aliens landed briefly on earth and left behind artifacts of their advanced civilization. The whole area where the aliens landed, called the Zone, is not only declared off-limits by the government but is a place where normal laws of physics do not apply, making it a minefield of perceptual illusions, booby traps and shifting geography. The novel’s title is metaphorical, echoing humans who go on a picnic and leave behind food and debris for forest animals. In the novel humans become the equivalent of animals, entering the zone in search of potentially valuable artifacts left behind by the aliens.

Stalker is a landmark film which defies genre categorization by eschewing the usual trappings of the science fiction genre. Tarkovsky himself railed against the very idea of genre, arguing instead that the great directors are a genre unto themselves. But while Stalker shows little evidence of the conventions of science fiction (future technologies, space travel, SF hardware, etc.) it does contain science fiction thematics in its formal treatment of time-space, represented through the ‘zone’s’ non-rational treatment of physical space and time. As the guide says, time and space do not move in a linear fashion within the zone, and you can never trace your steps back because what was once may not be anymore. Temporality is one of the science fiction genre’s most popular subjects, only here Tarkovsky treats it in a more philosophical sense than the usual ‘time travel’ quandaries usually found in science fiction films. And his formal treatment of time through agonizingly slow dolly shots, long takes that defy rational time-space, and oddly elliptical editing does not produce the sort of exciting, puzzle-like plots of the time travel science fiction.

Rick Altman’s theoretical breakdown of genre into its semantic and syntactical elements sheds light on how Stalker can still be considered science fiction, even when it doesn’t necessarily look like one. In Altman’s breakdown, each genre can be broken down into its semantic (surface elements such as conventions, visual iconography, etc. ) and syntactic (relational patterns such as plot, theme, meaning) elements. This helps explain hybrid genre films, like Star Wars, which has the semantics of a science fiction film but the syntactics of a Western. Or the evolution of a genre, such as the pre and post-Code Gangster film, with the post-Code Gangster film continuing the same semantics as the Pre-Code gangster film (tough guys such as Cagney, Robinson, Bogart in fedoras, dark sedans, sporting Tommy guns) but with a changed syntactics (now the gun-toting, tough guy character is a G-man on the side of the law). In this respect Stalker has very little of the usual science fiction semantics but does concern itself with many science fiction syntactics (mainly the philosophical exploration of the relationship between humanity/art and technology/science). In short, the sociological implications of advanced technology and the loss of spiritual values, which are the sort of ideas often dealt with in science fiction literature, if not often film. Stalker also shares another popular science fiction thematic: a concern for the earth’s environment. Seen from today’s perspective, it is one of the first films to treat the toll of materialism and 40 years of Soviet Communism on the environment.

A theme common to all the Russian SF films in the Fantasia series, on a general level, is travel. In a few cases the travel is of the classic SF variety: space travel to far away planets or interstellar travel (Planet of the Storms, To the Stars By Hard Ways, Cosmic Voyage), while with Stalker there is some physical travel –three men ride a trolley car from the inner city to an area known as the Zone on the city’s outer limits– but the real travel is of the internal kind (characters in varying states of self-questioning, spiritual or moral investigation); small scale physical travel has grave consequences in the dystopian Zero City, where a Moscow engineer travels on official duty to a bizarre small town to investigate the alteration of air conditioners, and Amphibian Man, where a scientist’s part-human, part-fish son sneaks away from his father’s secretive underwater lair to experience the temptations of a small coastal town.

It is interesting that two of the space travel films, Cosmic Voyage and Planet of the Storms, harbor messages of individual self-drive that would seem more fitting in an capitalist American film than in a Communist Soviet film, where the collective (i.e. the state) is valued above the individual. In Cosmic Voyage an astronaut feels weighted down by Soviet governmental bureaucracy, so decides to fly to space without the approval of the “Moscow Institute for Interplanetary Travel.” In Planet of the Storms, the second Soviet science fiction film to involve Venusian travel (after Road to the Stars, released in 1958), one of the main cosmonaut characters spouts the revealing line, “My life is my own.”

In Planet of the Storms a meteorite destroys one of three spaceships, the Capello, on their way to explore Venus. This puts the remaining two three-manned spaceships, Sirius and Vega, in the difficult position of waiting for the necessary third ship, which is slated to arrive in four months, or landing one ship onto the planet while the other remains in orbit. They send one ship down, but it crash lands, which complicates their mission. They now send two of the cosmonauts from the sole orbiting spaceship down on a rescue mission, with a single cosmonaut woman named Masha, chosen to remain alone in orbit (not a sissy task given the difficult decisions she will have to face). Although the film does contain the requisite love interest between Masha and one of the astronauts, it is hardly played up and is inconsequential.

Before they land on the planet’s surface the cosmonauts turn on the external microphones which pick up the usual eerie SF sounds, but also what appears to be human-like chanting, possibly of a female voice. This is an important moment because it establishes a key element in the mood of the planet —sounds and sound effects which add an ethereal quality to the proceedings— but also sets up the finale, when the source of the voice is sighted. It may be opportune to note that the science fiction genre has been at the forefront of sound film innovation, with such films as Them, Day the Earth Stood Still, Planet of the Apes, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Solaris expanding the horizon of instrumentation and the use of electronic sounds.

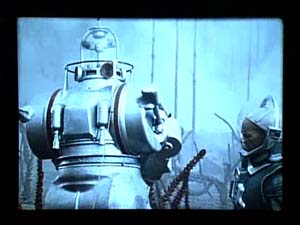

Twenty minutes into the 83 minute film the cosmonauts land on planet Venus, at which point the film alternates between interesting visual landscapes and tepid action scenes for the balance of its remaining hour. One of the bodies on Venus is the crew robot, John, an obvious copy of Robbie the Robot from Forbidden Planet. But parts of his behaviour also foreshadows 2001 (and other SF literature stories of the android who goes adrift and causes potential harm to the humans). In this case the humans rely on John the robot for a great deal –spatial co-ordinates, temperature and mass locations, giving out medication to the astronauts after they become delirious, etc. In one scene the robot ties a rope around its body to pull down a huge tree that forms a bridge that enables them to walk over a gulley (an image that recalls a similar moment in King Kong, 1933).

Only moments after landing, one of the cosmonauts is attacked by a not too convincing oversized Venus fly trap plant. Another alien attack comes from a pack of miniature (men in suits) Godzilla-like reptiles, which are easily gunned down. The other alien sighting is a brontosaurus (a more convincing visual effect than the other creatures).

The inclusion of species that once roamed on earth is an odd plot point, since the logistical-evolutional reason for this is never mentioned (not to mention the extremely rare chance of such a thing happening). Even within historical context, the special visual effects of all the ‘creatures’ encountered on the planet are not nearly as convincing as other visual elements of the planet (lighting, sets), which remain atmospheric and engaging. The film stands the test of time through its moody and evocative visuals. The constant fog, low key lighting, bluish tint, shadows, and craggy mountains give the film a gothic feel more in line with Mario Bava’s later Planet of the Vampires (1966) than earlier American SF films. The planet first seen from afar is enshrouded in fog –the first of several vague connections that can be made to Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1971). Another hint of Solaris, in terms of thematic, is how the presence of ‘earth’ (through nature, like the animal life below water, the plants, trees, vegetation) co-exists on this alien planet. At times the natural environment looks as it would on earth, while at other times it looks off, as if it were created by someone working from vague memory. There is also a sense of indeterminacy in how the landscape and climate changes from one scene to another: a water drenched site in one moment, dry and mountainous in another moment, culminating in an impressive volcanic explosion of molten red lava, which causes the robot to short circuit itself as it carries two men across a lava bed (this is treated as a form of sacrifice, with the musical score and the close-up of the teary-eyed cosmonaut Kern, who was closest to the John the robot). (One wonders whether Tarkovsky may have been influenced by this changing geo and biosphere and mannered depiction of nature for Stalker?) All of this, coupled with the atonal and experimental music, gives the planet its weird atmosphere.

Another less than convincing alien threat comes from a swooping pterodactyl that causes the cosmonauts to sink their hovercraft below water. This action scene leads to an important plot revelation which will bear meaning at the film’s conclusion: the discovery of an underwater cave which houses the remnants of an earlier intelligent species evidenced in a sculpture of a dragon with a red ruby as an eye (foreshadowing the mask found in the cave in Last Wave, Peter Weir, 1978). With their ship drowned, the men now appear stranded on the planet. Cosmonaut Masha must now decide whether to adhere to orders from Earth to remain in orbit, or drop down below to rescue her crew from the planet. The cosmonauts manage to return to the ship and find a tape recorded message left behind by Masha announcing her plan to land on the planet’s surface (reminiscent of the filmed suicide message left behind for Kelvin by Satorious in Solaris); however, the cosmonauts soon realize that, based on the timing of the message, she could not have landed on the planet’s surface.

The film ends with a pregnant moment of poetic beauty (somewhat foreshadowing the ending of Solaris). As they are about to set off from the planet’s surface, one of the cosmonauts cracks open a rock and finds within it a white porcelain like sculpture formed in the image of a female face with a vague Egyptian-styled head.

The man begins to yell that they can’t leave because “they are like us”… he boards the spaceship moments before blast off. The film then cuts to a small body of water on the planet’s surface. A water reflection moves into the camera’s view, giving us a clear yet abstracted image of the planet’s life form: we can make out a long white gown, the protruding head, and long arms which raise themselves as if saluting the space ship (a reference to the God Narcissism?). We also hear the same distanced, ethereal female voice from earlier. It is interesting how art plays a role in this finale –first in the sculpture found in the underwater cave and then in the figurine hidden in the rock– by being the signifier of an advanced civilization.

There are clearly moments in Planet of Storms which will produce laughter and snickers from contemporary audiences: a Soviet sing song which thanks the planet for its knowledge; the jazzy/poppy music played by the robot; the sentimentality accorded to the robot’s death scene; and the moment of ‘zero gravity’ when Masha takes off her magnetic boots and floats in the ship as an expression of her joy over the safety of the men.

But when compared to other American science fiction films of the time Planet of Storms holds up remarkably well on the back of its visual atmosphere and overall attention to scientific detail.

First on the Moon (2005 Alexei Fedorchenko) –the one film covered here that did not play at Fantasia– was a real revelation. First on the Moon does for pioneering in space travel what Forgotten Silver (Peter Jackson, 1995) did for pioneering in filmmaking: introduce a fictional figure/moment that rewrites its history. In this case through the machinations of plot, montage and stylistic complexity, this mockumentary demonstrates that the Russians beat the Americans to the moon by a good 30 years (1938 to be exact, right smack in the middle of the Stalinist purges). If you thought that the mockumentary was an exhausted form, well think again with this wonderful Russian film that mixes real archival footage with faked Soviet styled newsreel and propaganda footage from the Socialist Realist period (although Stalin only appears once briefly in the film). The replication of the 1930s style of Soviet newsreel and propaganda ‘agitprop’ is remarkable; only on a few occasions does director Fedorchenko’s style get the better of his conceit, with, for example, very long lateral tracking shots inside a space design factory or the Sokorovian sequence the night before the astronauts fly off, where the camera remains high angled and static looking at the five chosen cosmonauts (one woman, one midget) drinking and living their final tense minutes together before blast off.

The film opens with a newsreel about a meteorite that fell in the mountains of North Chile in 1938 (the use of a Latin American setting and a conspiracy theory makes this a distant cousin to Craig Baldwin’s Tribulations 99). This wrap-around scene catches up with itself about 60 minutes into the narrative, where it becomes loaded with more historical meaning in the full breadth of the film’s conspiratorial narrative: a cover-up over a Soviet spaceship that crashed on a return flight from the moon. Director Fedorchenko intercuts between key historical figures represented in the faux documentary footage, mixed with some authentic material and contemporary color interview footage with some of the same people or witnesses. In some cases they are filmed viewing the newsreels in preparation for their interview. A brief exposition on the pre-modern history of space flight leads to the first and most important figure, the equivalent of ??Forgotten Silver??’s neglected film pioneer Colin McKenzie, ‘observation object #1’: Ivan Kharlamov, the pilot of the first manned Soviet spaceship. Key points that reference the Soviet propaganda films are the sports footage –sports and healthy bodies being an instrumental factor in the Socialist Realist society (exemplified by the strikingly beautiful female pilot, Nadezhda).

Color footage of a camera dollying backwards along a government film archive rack establishes a sense of formality. We see footage of the astronauts in training. The plot thickens when we get the news line: ‘classified space rocket project employed 1.5 million people,’ and the scene cuts to classic Soviet propaganda ‘factory work-is-good’ footage. Fedorchenko intercuts footage from one of the first and most important Soviet SF films, Flight into Space (Cosmic Voyage by Vasili Zhuravlev, 1936, which also showed at Fantasia), creating a sense of historical validity for the mostly faux footage, and sets up the implication that the film itself spurned the Soviet government to initiate a real space probe. The seemingly successful blastoff of the rocket ship is followed by a sublimely convincing montage of celebrating Soviet Communists: people cheering with manic smiles, shot in low angle, perfectly replicating the mode of classic Soviet Socialist Realist art.

After the euphoria, a dissenting voice enters the fray through a Tarkovskian line spoken by the bed-ridden camera operator of the 1930s footage: “There is no such thing as progress, technical or moral.”

We now shift to the conspiracy side of the mockumentary, as the KGB become involved in a world wide search for evidence leading to the possible sighting of the ill-fated rocket’s ship pilot, Ivan Kharlamov. Film footage is confiscated and burned. People who knew Ivan are interrogated. In one harrowing scene, a ‘hidden’ camera –one section shows us a silent, tiny camera that easily escapes notice– reveals poison gas leaked into a room, hooded military men entering the room, taking a body out on a stretcher. We discover that one of the older men died during the making of the film –implication being that he may have been killed.

We discover that the whole rocket ship project was covered up, nearly successfully if not for one thing: the evidence of found pieces of the rocket ship. One of the people interviewed, the midget astronaut, reminisces about a circus performer who went by the name of Alexander Nevsky (the Grand Prince who led Russia’s military defense and saved Russia from Teutonic attacks). Which links the film back to the 1938 fallen meteorite (1938 also being the release date of Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky), an event to which the film now returns. The crash was not a meteorite, as told in the cover-up, but the rocket ship landing back on earth. Some debris was found (after the government cleaned the area), including a portion of the ship, which solidifies the conspiracy theory. The time from the blastoff to the landing was only 8 days –but is that long enough for the revelation at the end to even be possible? We find out that Ivan did not die in the crash but survived, living in Chile, after being placed in a psychiatric ward for a short while in the Philippines, where he may have married. The KGB only get a trace of Ivan in 1968, one year before the US Apollo 11 moon landing. The film ends, like Solaris and Planet of the Storms, with a ‘wow’ effect. The final scene is the conceit played to its end point: we see the film footage which was recovered in the crash in Chile and now preserved in the “Natural History Museum of Antofagasta”: shaky aerial footage of a lunar landscape landing. The camera cuts to another spatial location, unclear where, what, but what is clearly visible is the silhouetted backs of the original rocket ship crew of the 1938 flight: the midget, the woman, and three other men. The image is stark and oddly framed. The image looks like a smooth, flattened floor with odd round white markings, and a darkened, round halo filling in the extreme background. Is this the moon? (It looks more like the finale to The Beyond.) How did Ivan get back? The film ends with this narrative ambiguity which keeps the fallacy of the whole film alive.

To the Stars by Hard Ways (Richard Viktorov) was first released in 1985, but the print screened at Fantasia was the newly restored version that was shorn of 20 minutes and re-edited by the director’s son Nikolai Viktorov in 2001. Viewers may be familiar with the film through the neo-camp treatment given to it by the Mystery Science Theatre in its truncated version, Humanoid Woman, but To the Stars by Hard Ways has gained a cult-classic status among Russian youths who were attuned to the film’s marvelous blend of pop social commentary and stunning visual alchemy. To the Stars by Hard Ways is a space opera that has something for everything, managing to shift tones from camp, to hard science, to message film (on the environment and vitro-genetic engineering), to poetic touches of Tarkovskian influenced naturalism (and wonderful 1980’s synth/Tangerine Dream style instrumental music).

The film can be divided into seven distinct parts. In part 1 The Soviet Starship Pushkin comes across an abandoned spaceship. They investigate and discover a single living humanoid among many dead fetuses hanging in incubators –a wiry, white-haired gynoid named Neeya (played by the stunning model-turned-actress Yelena Metyolkina). This scene lasts about 6 minutes.

Part 2 can be referred to as “debating Neeya,” as Dr. Sergei Lebedev (Uldis Lieldidz) and a group of scientists and officials debate what to do with the female humanoid. Everything about the way the scene is staged, with the scientists on one side and the family/Neeya on the other, the earthy, ‘organic’ set design –the wood cabin, and natural colors of the cabin, the dacha setting– recalls the beginning of Solaris, where cosmonaut Berton is grilled by officials over his Solaris report. Doctor Lebedev convinces the officials that the best plan is for him to ‘adopt’ Neeya into his family so that he can better study Neeya. Lebedev is aided by the benevolent Professor Nadezhda Ivanova (Nadezhda Semyontsova), who straps Neeya to a brain reading machine.

Part 3, which deals with Neeya’s ‘immersion’ into Soviet family life and presents some ‘fish out of water’ humor, is by far the ‘campiest’ section of the film (and lives up to the soap opera aspect of space opera). Neeya learns about human behaviour through doctor Lebedev’s family –his father, his goofy son Stepan (Vadim Ledogorov), his mother, his daughter Tanya, and the family’s robot maid, who provides much of the campy humor; as does the scene at the beach where Stepan’s female admirer competes with Neeya for his attention. In this scene the Dr. Lebedev scolds Neeya for raising her arm at a human, recalling Isaac Asimov’s 1st Law of Robotics: “A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.” Showing her human side, Neeya is emotionally hurt and attempts suicide by jumping into a lake. A camp moment of Soviet-styled patriarchy comes when Stepan learns that Neeya was designed to be obedient, and then says, “she would make a good wife.”

The overall bluish tint of this section gives way at times to sepia colored memory flashes, as certain actions trigger Neeya’s memory of her past, which seems to be blocked from her immediate memory recall. Nature is depicted in its most splendid, vivid colors, unlike the bluish tone of the domestic scenes.

Neeya –who seems to possess the power to control nature–causes a wind storm to increase in ferocity (although the change in color may suggest a fantasy state) and then we see a Tarkovskian trick of the eye as Neeya seems to materialize and disappear in a reflected mirror shot (I’m thinking here of the disappearing vapor on the table in Mirror).

Nature seems to trigger her memory, as when her suicide attempt cuts away to a series of sepia shots of her creator/father. In one scene there appears to be a homage to L’avventura, which would make sense thematically with the idea of a woman caught in an ‘alien’ place (a working class woman mingling with the bourgeois class in L’avventura and a humanoid mingling with humans –interspecies alienation– in To the Stars by Hard Ways. A clever deception opens a scene with what looks like a behind the shoulder two-shot of a blonde and black haired woman. The camera pulls back to reveal Neeya wearing a black wig and holding up a blond wig in her other hand. She then sits down at a desk in front of a mirror and looks at herself as she tries on different colored wigs, as does the Vitti character Victoria in the Antonioni film.

Part 4 deals with Dr. Lebedev, his son Stepan, and few others preparing for a space flight. Once on board we see that Neeya, who was refused permission to join them on the flight, usurps their authority after receiving a premonition to return to her home planet, Dessa. Like Solaris, the actual space travel is handled in a few brief shots, including a reverse shot of Neeya being sucked back along a corridor, away from the camera.

Part 5 concerns the actions of the crew members while in orbit before landing on planet Dessa, and lasts about 25 minutes. We see the different crew quarters, the ship’s corridors, the transport areas, the medical bay, and the gadgetry-filled walls.

The scene includes some forced comic relief in the form of a hypochondriac alien life force, a fish-amphibian-like creature housed in a water container, that Stepan has been given the unenviable task of caring after. At roughly the 40 minute mark the space orbit setting gives way to a flashback (sepia again) of a white haired figure, Ambassador Rakan (Igor Ledogorovather), surrounded by a slew of android-children –Neeya being one of them– who have been created for the sole purpose of helping rectify the planet’s environmental disaster.

This scene has one of the most Tarkovskian moments: a 60 second long take of scientists walking in and out of frame, their backs facing each other and criss-crossing spatially as they debate the ethical ramifications of a decision taken.

Part 6 is the longest part of the film, running from approximately 76 minutes to the end (115 minutes) and is the highlight from a purely visual standpoint. In this section the ship lands on Neeya’s home planet Dessa, and we discover first hand the extent of the planet’s environmental destruction. The planet’s eco-system is so polluted that the inhabitants must live underground and can only surface wearing masks, which are controlled by a despotic midget capitalist (Kiki) who exploits the inhabitants at every turn. The cosmonauts begin to clean the planet’s eco-system, transforming acid to a purifying rain. One of the astronauts begins to jump for joy in the rain shower, a pure camp-retro propaganda moment in the style of the 1940s Socialist Realist World War 2 films. In this section the film dishes out its strongest propaganda message against rampant, resource-wasting industrialism and the value of team work over individualism. In a last ditch effort to derail the collective efforts to repair the planet’s eco-system, the despot Kiki uses mind control to coerce Neeya into destroying the Astyra spaceship which is spearheading the environmental repairs. The death of Professor Nadezhda Ivanova, the scientist/mother figure who treated Neeya during the earth family scenes, gives her the extra strength to break free from Kiki’s mind control and help complete the planet’s regeneration. This is achieved in a singular poetic ‘synecdochic’ moment when a threatening amorphous ‘biomass’ is magically transformed by the collective touch of Neeya and the others into a positive energy force. As the ‘blob’ nears the group the scene cuts to an overhead shot where we see pairs of hands reaching out and grabbing at the amorphous blob, stretching it like dough, and transforming its energy into positive, regenerative force. In fact, the blob symbolically changes into a bowl of wheat, recalling the classic Socialist Realist collective farm films, only here technology is replaced by an alien monster. The film concludes with Stepan trying to convince Neeya to leave with him, but she decides to stay on her natal planet; the camera cranes up and away as she raises her hands in a gesture of goodwill –and transmittance of her powers?– for their journey home (also recalling the final images in Planet of Storms).

Amphibian Man (1962, Vladimir Chebotaryov, Gennadi Kazansky) opens with a montage of a small Latin American fishing community’s alarmist reactions to sightings of a ‘sea devil’ that has been terrorizing the local community. On board a small ship a pearl king, Captain Don Pedro Zurita (Mikhail Kozakov) mistreats his workers, which alienates him from the attractive woman he desires, Gutiere Baltazar (Anastasiya Vertinskaya). When Gutiere jumps into the water to evade Pedro’s advances, a shark sighting alarms the boat workers, but only Pedro jumps in after her. The supposed sea devil –a humanoid dressed in shimmering silver body suit and oddly shaped headpiece– saves the woman from the shark attack.

Pedro, who has been skeptical of the sea monster, now becomes a believer when he sees the sea devil return Gutiere to the boat. Taking credit for killing the shark, Pedro uses this as leverage to coerce the woman’s father, Old Baltazar (Anatoly Smiranin), into giving consent for his daughter’s hand in marriage. Meanwhile a newspaper journalist, Olsen (Vladlen Davydov), visits the reclusive Dr. Salvatore (Nikolai Simonov), who lives in an ivory tower laboratory, decked out in cubist/art deco design.

We learn that the sea devil is indeed the doctor’s son, Ichtyander Salvator (Vladimir Korenev), who had a fatal lung disease as a boy which the father cured with a shark’s gill transplant. The transplant gave his son the ability to swim underwater for long periods of time. (For the underwater scenes Korenev was played by Leningrad underwater swimming champion Rem Stukalov.) The doctor tells Olsen of his plans to build a ‘classless’ utopian, underwater society by giving all humans a shark gill transplant! Olsen, who plays the level-headed socialist to the doctor’s utopianist, doubts that human nature –greed– will be any different underwater.

The doctor (who has been referred to by Old Man Baltazar as ‘god’ for his ability to cure the villagers of illnesses) here plays the role of a Socialist Dr. Frankenstein: ‘creating’ a son who is isolated and alienated from the world by his ‘difference’ (some have compared the son to Edward Scissorhands). The four central characters each represent an ideological position: Ichtyander is the Candide-like innocent communist who reacts with common sense to what is around him (emotional Communism); Dr. Salvatore is the autocratic, single-minded scientist willing to sacrifice his family for his ideals; Olsen is the level-headed communist; and Don Pedro is the rampant, bottom line capitalist. Each of the first three characters wants to help society in their own way (Olsen’s being the most rational and commonsensical).

As an interesting side note, the geo-political stratification represented in the film is a common science fiction thematic/convention. There are many classic science fiction films and/or novels in which the rich/poor duality is dramaticized literally and figuratively in physical terms, with the poor and the rich being set-off geographically (usually down/up). Think of the slave workers living underground and the owners living in their celestial palaces in Metropolis; the peace loving Elois who live above ground and the cannibalistic Morlocks who live underground in Welles’ The Time Machine (and the film versions); the remaining humans who are forced to live underground in opposition to the all-powerful apes who live above ground in The Planet of the Apes series; the remaining humans who live below ground in La Jetée; the select rich who live in floating cities above the poor and the replicants living below in overcrowded cities in Blade runner; plus such utopias as Plato’s Lost Underwater City of Atlantis, the mountain-hidden Shangri-la in James Hilton’s fantasy novel Lost Horizon, etc. Hence Dr. Salvatore’s utopian dream of a classless, underwater society, while ludicrous on paper, is well within the tradition of science fiction and fantasy.

After saving Gutiere, Ichtyander is stung by the love bug. His desire to see Gutiere again draws him away from his father’s teachings to visit the outside world for the first time in his life. This leads to one of the best scenes in the film: Ichtynder’s walk through the city –a literal ‘fish out of water’ moment where the city (at first at night) feels overwhelmingly tactile, visceral and alien to his virgin eyes. His social awkwardness and ignorance of human reality is evident as he stares at every woman in search of Gutiere.

This is where the Cuban setting is put to good use, with the bold, Western-styled neon lights and brand name marquees –remnants of the pre-Cuban Revolution era– stick out like an alien landscape to both him and us. While he slickers through the city at night, with mouth agape, we hear a female voice singing a song about, essentially, himself, the famous ‘sea devil,’ the voice being given a body for a brief moment when a torch singer is sighted through the night club store front. Night gives way to day –the transition made odd by an extended shot into the distorted city imagery of a concave mirror, which opens on a Mercedes Benz insignia.

The surrealism of these events as seen through his eyes continues when he seems overwhelmed by the sight of a cow being transported off a ship by a crane. He rushes off to where he feels most comfortable, the sea.

The other odd trappings in the setting is the Christian iconography (Gutiere always wears a cross and we see them at the church where she marries Pedro). While this Christian iconography makes sense with the Mexican (or Latin American setting), I wondered whether this Christian iconography was found on-location or whether it was a result of set dressing.

Much of the ideological meaning in Amphibian Man comes in the daytime town scenes, when we see Ichtyander shocked by the poverty he sees around him (street urchins, gypsies, nervous street vendors) and solves the problem by taking immediate action: stealing fresh fish off a vendor’s cart and giving it to the people. This leads to chants of ‘he’s crazy’ which are replaced by ‘he’s a crazy millionaire’ after he gives the vendor a wad of bills. This leads to a chase through the city by the local police, who he eludes by jumping along rooftops and back into the ocean.

Don Pedro exploits Ichystander’s underwater skills by getting him to swim for pearls, and then conspires to have Dr. Salvatore and his son arrested. The scene where Don Pedro visits Dr. Salvatore in his prison cell is the most striking manifestation of the film’s communist demonization of capitalism: Don Pedro is framed to look like the devil, with striking lighting/high angle to emphasize his pointy beard, dark eyes and eyebrows, and horn-like hair.

The prison is one of the most interesting sets in the film, a cross between William Cameron Menzies’ art direction in Invaders From Mars and the art direction in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Justice is served when Pedro dies at the hands of the poor, stabbed by Old Baltazar. Olsen rescues Ichtyander from prison, but his long stay in a prison water tank has affected his lungs and he must now live the rest of his life underwater. This leads to the typically tragic/sad ending common to Russian cinema, as he bids a farewell kiss to Gutiere and then walks away slowly into the sea, with sunlight reflecting and glowing off the water’s surface. This is a classic image of the ‘monster’ (Godzilla, The Creature from the Black Lagoon) returning to its natural habitat. Like in To the Stars by Hard Ways, the villain of the piece is a rapacious capitalist who lives to exploit for money. However, this film is more nuanced in its ideological characterisations than To the Stars by Hard Ways, with science and naive Communism both coming in for at least some mild critique or skepticism. In the end it is Olsen’s more down to earth approach to poverty that wins out. Being left alone at the shore with Gutiere, there is also the suggestion that with Don Pedro and Ichtyander out of the way, he may end up with Gutiere.

The Amphibian Man, which was released in the same ‘thaw’ period (1957-1962) as such classics as The Ballad of a Soldier, The Cranes are Flying and Ivan’s Childhood, was a huge hit in the Soviet Union in 1962. It is one of the most unusual films to come out of the Soviet Union, a tragic love story that is equal parts Frankenstein, Creature of the Black Lagoon, and The Little Mermaid. Although the film has clear elements of Communist propaganda –epitomized ideologically by the demonization of the capitalist Don Pedro– it is also a wondrous fantasy filled with charm, enchantment and imagination. This latter quality is particularly evident during the many underwater scenes, like moment when Ichtyander fantasizes a life with Gutiere, swimming together like a pair of dolphins; and in the scene of Ichtyander’s first ever contact with society, where the town’s neon signs, architecture, and activities are given a surreal patina to reflect Ichtyander’s sense of amazement and new found freedom. Though thematically unusual, Amphibian Man comes closer than any of the other films at recalling the aesthetic qualities of the great Post-Revolution Soviet classics. For example, throughout the film we are treated to some striking Soviet styled framing, with actors often shot in bold close-ups, with top heavy, low angle framing and objects intruding into the edge of the frame.

Taken as a group, the science fiction films featured at Fantasia 2007 showcase a diversity of style, subject and theme. The range is perhaps best expressed in the two films not discussed in this essay, Cosmic Voyage (1936) and Zero Days (1988). The period in question (1936 to 1988) symbolically marks the journey from the heady, idealist days of Soviet Communism, reflected in ??Cosmic Voyage??’s faith in scientific endeavor, to the gloom and doom days of the end of Communism, expressed in ??Zero City??’s Kafkaesque dystopian vision.