Le Mépris: Analysis of mise-en-scène

‘C’est un film simple sur des choses compliquées’

(Jean-Luc Godard)

Godard’s above statement is an appropriate description of his film Le Mépris: the plot of the film is, after all, banal, while at the same time complex. Banal because it develops the dissolution of a couple in a coherent and logical way; complex because the end of love is a matter which concerns psychological sensations and internal emotions, which is work more suitable for a novelist than a film director. To film fading emotions is one of the most difficult things for a director: it means, simply, to make the invisible visible. For that reason, it will be necessary to analyse in detail the mise-en-scène of Le Mépris and the way in which Godard constructs the story of –to quote the words of André Bazin placed as an epigraph at the beginning of the movie– “un monde qui s’accorde à nos désirs” (“the cinema substitutes for our gaze a world more in harmony with our desires”). [1]

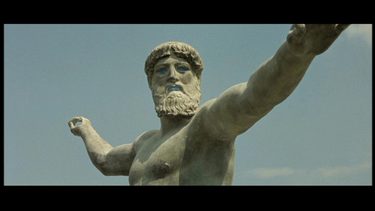

The banal part of story is the end of a marriage, triggered by a wife’s (Camille, played by Brigit Bardot) contempt toward her husband’s (Paul, played by Michel Piccoli) indifference, blended with the meta-narrative of the making of a film based upon Homer’s Odyssey, directed by Fritz Lang (who plays himself). But in Lang’s pessimistic vision, Odyssey is not about the fidelity of Penelope and Ulysses’ will to return home to Ithica, but rather it is about the contempt of a wife towards her husband who has decided not to return. In his modern vision of life, it is a film, as he says in an explicit way (quoting Hölderlin), about ‘the absence of the gods,’ which reflects, as in a mirror, Godard’s opinion on modern society: that nowadays gods are substituted by idols, mere mortals that conventions make near divine (such as a movie producer who throws a film can like an ancient Olympic athlete tossing a diskus, or a movie star, etc.). This struggle between reality and cinema is perhaps the most intriguing part of the film, one which makes it complex and dense in meaning. For example, the representation of divinity is now possible thanks to the cinema, an art which can still be pure and immaculate (as the panoramic shots around enormous statues of gods indicate). Art vs. Industry is another theme of Le Mépris: the purity of cinema, in opposition to a mercantile society embodied by the film-within-a-film producer, Jeremy Prokosch, played by Jack Palance, who hires a writer (Paul) to rewrite the film he is producing, Odyssey, to make it more commercial.

Set entirely in Italy, between Rome and Capri, Le Mépris is full of contradictions: not only of character, especially the female protagonists, but in the way Godard chooses to set a modern tragedy in the centre (Rome) and south (Capri) of Italy, and even in the summer, where light and sunshine reign. Obscurity of feelings and darkness of the soul versus the splendour and majesty of a nature indifferent toward human misery. Not only can Italy stand-in for ancient, epic Greece but in Rome there is the useful Cinecittà studios, where parts of the film were shot: but the strong light of the Italian sunshine does not warm human hearts or enlighten the consciences of the characters. Nevertheless there is nothing epic in this modern world: light remains brilliant but it is no longer a mirror of the soul; it does not clarify the relationship between husband and wife; on the contrary, if ever it dazzles and further blinds their vision and thoughts, they would not recognise each other; in the beginning of the film they are in the (muted) darkness of their welcoming but illusory bedroom. A bedroom which is an alcove of a love but which hides contempt, misunderstanding, and mistrust, much as the darkness hides their faces and expressions from each other. In fact, right from the beginning Paul admits to love Camille “totally, tenderly” but also, with a worrying and ominous adverb, “tragically.” And, of course, she too.

This ironic contrast between light and dark also allows Godard to quote, in an explicit way, one of his favourite directors, Roberto Rossellini, whose Viaggio in Italia, the story of a bourgeois couple in a state of marital decay, can be seen as a neorealist version of Le Mépris. In another curious contrast, Godard showcases Louis Lumière’s well-known pessimistic statement about the cinema, “The cinema is an invention without a future,” in bold letters on the wall of the preview room.

There is more: in Le Mépris, once the characters reach the villa in Capri, the sea becomes very important. The sea is the obvious setting for the Odyssey scene with sirens. And sirens represent temptation, a female enigma that Ulysses himself can not understand and, therefore, prefers to avoid rather than fight. Blonde hair (although we see Bardot donning a black wig in the Rome part, another ‘contradiction’), intriguing sunglasses, fleshy lips, the siren of the modern world described by Le Mépris is Brigitte Bardot, at the same time victim and executioner of love, of her beauty and its power, of male philosophy. Like the sea, she is absolutely inscrutable, an element in an eternal state of movement and turbulence even if she appears constant and determined; however, if just for her contradictions, she is a vital element (as is water), the only one who can take a decision and decide to change her life. For that reason, she will die: no one has understood her because, first of all, she has never understood herself. Her death is something like a catharsis, as all the people who were involved with her have suffered her power: only nature and cinema, it seems that Godard suggests, can survive and will not be corroded by human events.

Fritz Lang will end his film and the last shot of the film (but not of the film-within-the-film) framing the sea, infinitely huge and alive. It is a strong presence in the Homer’s Odyssey and in this cinematic/real odyssey. Nature, often shot with slow, subtle, caressing camera movements, is the secret glue of the plot; it interacts with characters: it is the only thing, together with the cinema and the figure of the artist, to remain pure. They are, in Godard’s opinion, the only real gods of modern times: the rest is, to paraphrase Hamlet, silent. It is by the sea that Paul and Camille see themselves for the last time: she is having a swim, he is sitting on a rock. The vital sea, in this case, represents a barrier: just another of life’s contradictions.

Other sets that are used in Le Mépris, especially in the first Roman part, are the film-within-a-film set and the couple’s house. A film set is the place where pretence is created or, more precisely, a non-site built to create a world that agrees with our desires; but, in this case, this world greatly resembles the real one. But is art to imitate life, or vice versa? This struggle between reality and cinema is already present in the extremely concise prologue, well analysed by Jose Luis Guarner:

In a spacious yard, filled with sunshine, a camera tracks forward. As Raoul Coutard [who plays himself, only his name is spelled R. Kutard] turns the lens towards us, the credits (spoken, like those of The Magnificent Ambersons) end and we hear the words of André Bazin (Jose Luis Guarner, p. 54).

Guarner goes on to say that Godard “presents filming almost as a rite taking place before us” and that “not without a certain irony, the second scene of Le Mépris makes us voyeurs: we watch a long love scene (a love which shows not in gestures but in words) between Paul Javal and his wife Camille… The beginning of Le Mépris, like Rossellini’s Viaggio in Italia, gives us the sensation of discovering lives that existed before the film.”

There are many films that reflect the parallelism between life and fiction (from the silent classic Sherlock Jr. by Buster Keaton to Abel Ferrara’s Dangerous Game), but Godard’s is one of the most intelligent and illuminating. The couple’s conflict reflects another element of the relationship between art and industry within the world of the cinema: because their flat in Rome is unpaid, Paul accepts the re-write job on Lang’s Odyssey for the money. As Guarner brilliantly argues:

The nature of the conflict is expressed almost physically in the long scene in their apartment, an extension of the struggle between Michel and Patricia in ??A bout de souffle??… The décor, deliberately reduced to what is essential (a half-furnished apartment, a very simple palette in which white predominates), focuses all our interest on the faces and feelings of the characters. The painful insecurity which appears little by little in this confrontation as almost intolerable, comes not only from the consciousness of an increasing lack of communication (which Godard expresses very well through the frustrating movements of the characters who come in and out constantly without ever meeting face to face), but from the increasing inscrutability of Camille’s face (p. 57).

Their flat would appear large, if not for the widescreen format, which Godard uses to crush perspective and to always show Paul and Camille separated (by a wall, a door, a lamp, etc.), as if using a split-screen technique. Strongly opposing colours (red sofas, white walls) increase the feeling of anxiety and of the wife’s contempt; light invades the apartment; certain props become useful, such as a door without a panel which Paul and Camille sometimes open and other times leave shut and simply walk through, or the mysterious female statue (representation of the gods returns again) which stands up against the wall with her head bowed down, as if in shame for being privy to the domestic spat.

“The tension of the scene and of their struggle culminates in an interrogation, shown in an anxious shot that pans backwards and forwards [2] between Paul and Camille, who is alternatively switching a lamp on and off” (Guarner, p. 59). This is one of the most beautiful moments of the film: only a prop – a lamp turned on or off – confers rhythm and an internal sense of tragedy to the scene and to the characters, highlighting lights and shadows of their personalities.

Well then, what are these personalities? Evidently Camille is the main character, the engine of the plot; in the screenplay, Godard described her this way:

Calm as a sea of oil most of the time, even absentminded, Camille suddenly becomes stormy, by turns nervous, inexplicable. Throughout the film we wonder what Camille is thinking about and, when suddenly abandons her peculiar passive torpor and acts, this action is always as unpredictable and inexplicable as that of an automobile which, rolling along a fine straight road, suddenly jumps the curb and crashes into a tree. In fact, Camille acts only three or four times in the entire film. And it is these actions that provoke the three or four real surges in the film, as, at the same time, they constitute the film’s principal motor force. But in contrast to her husband, who always acts on the strength of a complicated series of rationalizations, Camille acts nonpsychologically, so to speak, by instinct – a sort of life instinct, like that of a plant that needs water in order to continue living… Though one might wonder about her, as Paul does, she never wonders about herself. She lives full and simple sentiments, and cannot imagine being able to analyze them (Collet, p. 94).

She is the most contradictory character in the film and Godard does not enquire about her beauty, he only casts doubts about her heart, records her perfidy, and only watches her movements. While Prokosch is an exaggerated, caricatured character – who, in his obsessions as an omnipotent god of the modern world, Godard shows us with a benevolent contempt – Lang represents not a god, but a noble and valorous king who, as Godard wrote, “through his monocle, he gazes at the world with a lucid eye.” But what is extraordinary in Godard’s mise-en-scène, is the fact that he avoids judging his characters in any definitive way. He prefers that they live their own lives. Certainly, we understand whom he has sympathy for, but this is also because these stylized characters are nearly transformed into strong archetypes.

Last but not least is Paul, “a character from Marienbad who wants to play the role of a character in Rio Bravo??” (Godard) and who “…embodies the tragic contradictions of Godard’s world: he wants to live in harmony with reality, like the ancients, but without participating in it, without absorbing it fully, in the passive attitude of a spectator watching a film?” (Guarner, pp. 59-60). I’ll quote Guarner again to benefit from the precision of his analysis: “Conscious of Brigitte Bardot’s limitations, he [Godard] has avoided adapting the character of Camille to the personal legend of B.B. and has tried the opposite course, starting from the fact that it is B.B. who plays Camille… During the course of ??Le Mépris, we never forget that we are seeing B.B. and not Camille, but we soon grow accustomed to it: we accept her acting just as we accept that Palance “is” Prokosch and Lang “is” Lang” (p. 59).

Finally, the sentence which encapsulates the meaning of the film and the traits of the protagonists, comes from Godard himself: “Contempt is the story of men cut off from themselves, from the world, from reality. They awkwardly seek their way back to the light, but they are enclosed in a dark room” (Collet, p. 94). Characters are prisoners of their reality, a reality created by Godard’s mise-en-scène: perhaps this time neither death nor the cinema will be able to free them. And the last shot frames the inscrutable sea again…

Endnotes

1 Although Godard cites this as a Bazin quotation, Godard is mistaken. The same quote is used by Godard again in his film series Histoire(s) du cinéma, “1a-Touts les histoires.” In the Histoire(s) du cinéma book the quote is sourced to Michel Mourlet, not Bazin. The exact location for the quote is from Mourlet’s essay “Sur un art ignoré” in Cahiers du cinéma, no. 98. Thanks go to Timothy Barnard for spotting this error and locating its proper allocation.

2 To be more precise, the camera movement Guarner describes tracks (not pans) laterally between Paul and Camille, not backwards and forwards.

Bibliography

Cameron, Ian (ed.), The Films of Jean-Luc Godard, Studio Vista, London, 1967

Collet, Jean. Jean-Luc Godard, Crown Publishers, Inc., New York, 1970

Lesage, Julia. Jean-Luc Godard: A Guide to References and Resources, G.K. Hall & Co., Boston, 1979

Guarner, Jose Luis. Le Mépris (in Ian Cameron, ed., The Films of Jean-Luc Godard, Studio Vista, London, 1967), p. 54

Narboni, Jean and Tom Milne (ed.), Godard on Godard, Secker & Warburg, London, 1968

Roud, Richard. Jean-Luc Godard, Thames and Hudson Limited, London, 1967

Sterritt, David. The Films of Jean-Luc Godard: Seeing the Invisible, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999

Dixon, Wheeler Winston. The Films of Jean-Luc Godard, State University of New York Press, Albany, 1997