Free Associating Around Whoever Fights Monsters

Semi-Random Thoughts about Improvisation, Jazz, and/or (a) Film in No Real Particular Order (Then Again, Maybe So)

In this essay, Brett Kashmere examines Ryan Tebo’s recent documentary Whoever Fights Monsters, a film which deals with the nature of improvisational music through a unique approach to the filmmaking process itself. Though the film features footage of eight contemporary improvisers doing their thing, which for some filmmakers would satisfy the improv quotient of a documentary on the subject, Tebo has gone many steps further than the standard for the genre: he has created a film that is not only about improvisation, but is itself constructed as an improvisation – or more precisely, as a particular improvisation. Tebo arrived at the structure for the film – right down to details of shot length – by patterning his audiovisual editing strategies after the structure of Ornette Coleman’s classic 1961 album Free Jazz. Kashmere explores Tebo’s process while offering insightful commentary on the relationships between jazz improvisation, filmmaking, and the way they have come together in this film. The result is a marvelous look into the potential for filmmakers to take the idea of “designing a film for sound” to levels rarely glimpsed in cinemas past or present. -RJ

The author wonders about The Gates.

Architecture is not spontaneous.

Holed up a half-block from Central Park on a transcendent October day readymade for outdoor revelry, attempting to appraise a non-fiction film on improvised music, at this writing I feel remarkably un-free. These cramped hotel jottings about ordered celluloid lensings seem at first thought (best thought?) a double act of second-hand “making.” Meantime, memories of Christo and Jean-Claude’s overwrought saffron Gates –erected last February near this same site – alight my mind, and confound. A grand experiment in logistical art, the Gates couldn’t be further from spontaneous creation yet they are dead at the centre of Whoever Fights Monsters (2006), a new experimental doc about free jazz by Boston area artist Ryan Tebo. How could anything so dull and contrived as the Gates be “scene” in the vicinity of mercurial, indeterminate and dynamic free-form jazz? 1 At worst, one wrong note.

“Whoever Fights Monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you” (Nietzsche 1968:279). Patterned after Ornette Coleman’s 1961 landmark recording Free Jazz, Whoever Fights Monsters proffers a cross-cultural side view of contemporary American and European free improvisation. Tensile, spring-loaded, multi-layered, like Coleman’s Free Jazz, Tebo’s Monsters features eight musicians: Tatsuya Nakatani, Ras Moshe, and William Parker from New York; Kent Kessler, Michael Zerang and Ken Vandermark from Chicago; and Dror Feiler and Mats Gustafsson from Stockholm. Like the Coleman ensemble, they’re organized into “double quartets” distinguished aurally on left and right channels respectively. Monsters’ unconventional approach to combining sound and image is the film’s most striking feature. As a point of departure each musician was presented a statement outlining Tebo’s own opinions about free jazz and free thinking, which they expound upon in an interview format. With mixed success, their responses are blended together, arranged and layered out of sync with their diegetic avatars and short musical solos, which were recorded immediately after the interviews. Overlapping dialogue and music on adjacent stereo tracks, for instance, obfuscates much of what the musicians say and which this viewer would like to hear. There’s also something visually infective (read: frustrating) about watching people talk without hearing their voices concurrently in sync. Nonetheless it’s an audacious strategy, ultimately successful, for it denies the omniscient testimony of experts in the same way that group improvisation destroys traditional hierarchies of bandleader and band, solo and assembly. Interspersed amongst the diffracted conversation, solo and collective play we also see these men performing domesticity: frying yummy-looking omelettes, hurriedly sweeping up, excitedly showing off treasured LPs, etc. Indeed, the film’s fun is located in the felt reciprocity between filmmaker and the musicians as they share time, food and discussion.

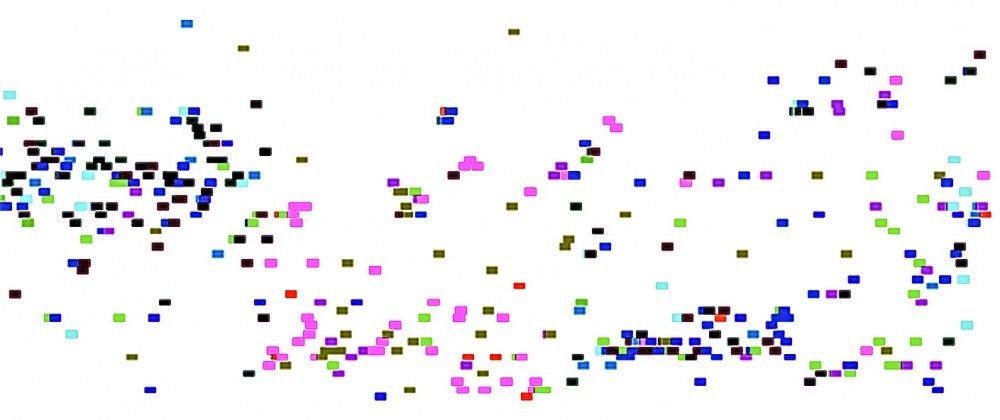

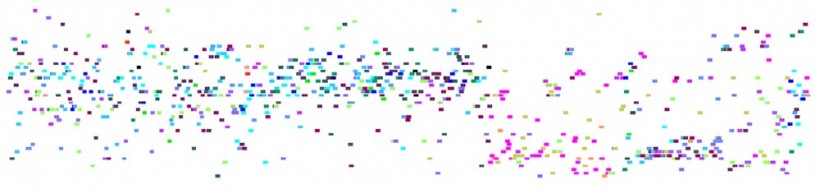

The 37-minute film was photographed on 16mm and Super 8 colour film, digitised, and edited according to the structure and length of Free Jazz. Tebo explains his compositional method: “I input the music [from Coleman’s continuous free group-improvisation] into Max/MSP [a graphical programming environment/interface] and analysed the pitch and amplitude after dividing it into fourteen [14] two-and-three-quarter-minutes [2:45] pieces. This created shapes, placed on a graph; pitch determined Y-axis position and amplitude color… In addition to this, I used the structure of the solos in Free Jazz to provide general solo sections within my film” (Tebo 2006:2). Tebo’s analysis of Coleman’s recording produced a graphical score (see above diagram), which was used in the editing process to determine approximate shot lengths and lengths of musical passages. Consequently, Whoever Fights Monsters is a radial admixture; the sound editing is seamless, the images fluidly interwoven. Each instrument and voice (and/or/as texture) leads naturally to the next, resulting in an uncannily coherent exquisite corpse-like assemblage.

Max/MSP analysis of Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz.

Tebo’s overall formal approach echoes certain technical strategies of free-form jazz, namely its broadened repertoire of expressive elements and individualistic modes of playing. Incorporating a full range of filmic grammar – lens flares and fogging, monochrome head and tail leaders, soft focus, “off” exposure, flicker, sudden zooms, fixed framing¬ and excited camera movements – he marks his presence as a creative collaborator. This is no camera-on-sticks, talking heads record; it turns on the tension of illustrating inspirational sources and getting in on the jam. Importantly, Whoever Fights Monsters is rooted in, and flows from, Tebo’s personal experience as an engaged, active listener. Although these are his heroes represented in collective portraiture, the film intentionally avoids history, negotiating a triangulation between first-person participant-observation, “documentary” information and experimental/improvisational aesthetics. It is made with the musicians rather than about them. This shared commitment to the creative process saves Monsters from the status of facile, de-clawed document of unconventional, insurgent art.

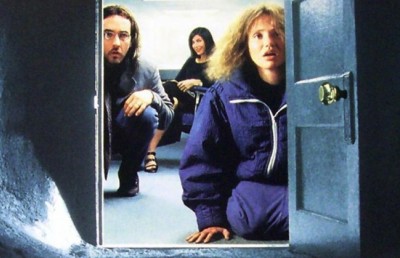

Ken Vandermark

in Whoever Fights Monsters

Improvisation is not a way of playing, but a way of living. Spontaneous activity requires boundless reserves of intuitive concentration, sensitivity, and openness. Letting go of prearranged, contrived patterns and musico-cultural clichés, these acutely tuned and risky sound situationists arm themselves (heart on sleave) with the inner vigilance necessary to destroy borders, divisions, status quos, racisms, and other outmoded ways of thinking (and therefore, challenge instruments of control).

Cinema, like jazz, is time-based. Both are characterized by time, space and rhythm; film is nothing more than music + light. Even when projected silent, film has an inherent pulse of twenty-four beats a second that engenders a haptic effect. Film audiences, too, have voices, are part of the celluloid’s unfurling act, and often make their opinions felt, either through yawns, guffaws, commentary or gasps of amazement. Conversely, music has a visual element; the memorable, visceral physicality of live performance, in concert with album photographs, publicity stills, instantaneous televisual coverage, and archival film and video footage, produces an imaginary/image that is retained in the mind’s-eye, providing listeners with a visual referent.

Improvising musicians and film experimentalists are similar creators. Their time-based, (usually) non-verbal expressions give shape and rhythm to inner landscapes that emanate out of the body. Over the years this similarity of expression has fostered a rich back-and-forth dialogue between jazz and film artists. John Cassavetes’ Shadows (1959), Shirley Clarke’s The Connection (1961), John Whitney’s Catalog (1961) and Michael Snow’s New York Eye and Ear Control (1964) demonstrate the affinity between vanguard filmmakers and modern jazz. 2 Meanwhile, Harry Smith’s improvised projections, presented alongside bebop artists of the 50s, Len Lye’s collaborations with jazz groups at New York’s Five Spot in the mid 50s, and Joyce Wieland’s mixed media presentations featuring free jazz musicians in the 60s, find their echo in recent screenings of silent experimental films with improvised soundtracks. Over the last few years Brakhage’s film The Text of Light (1974) has been projected with live musical accompaniment by guitarists Lee Ranaldo and Alan Licht, turntablists Christian Marclay and DJ Olive, and drummer William Hooker. Chicago’s Boxhead Ensemble (a rotating line-up of musicians that currently includes Michael Krassner, Fred Lonberg-Holm, Scott Tuma and Jim White) improvises soundtracks for silent experimental films by the likes of Phil Solomon, Paula Froehl, David Gatten, Jem Cohen, Julie Murray, Barbara Meter and others. And so on. Light hitting canvas reflecting physiological pulses onto bodies and out of instruments: is this not visual musical thinking?

When it comes to improvisation and performance, structures reinforce but intentions blur. “Performance is always at least slightly different from its plan, map, or orchestration” (Lhamon, Jr. 1990:218). Improvisation is abundantly imperfect, full of “missed” and/or “wrong” notes. Performances are constructed on the edge of failure, decisions are being made right now about it, possibilities are crystallizing out of memory, lights are going on. In need of a framework, improvisation often slips into the same ruts and alleys, re-tracing familiar grooves. Ambivalent and unfixed, repetition can be positive, though; it’s also the risk of working ideas out in public night after night. The difference between musical improvisation and improvised notation (stream-of-conscious writing and filmmaking are still closed forms) is that there’s permanence with the latter (keeping in mind that sound can also be recorded). Misspellings, missed exposures, missed notes: all these so-called mis-takes are not really such at all (speaking now like a damaged record, skipping: Broken music?) Do expectations play a/part of (experiencing) improvised performance? As John Corbett points out, “Improvisation is music to be played… it requires a different kind of listening in which the listener is active, a participant observer of sorts, much like the writerly reader, the ‘writing aloud’ reader that Barthes idealizes” (Corbett 1995:233).

Social forces engender new aesthetics. Back to the future. It is no accident that the two decades following World War II coincide with the most creative cultural period in American history. Art underwent massive renovations after the war, manifesting in a twenty-year period of sustained innovation and experimentation. The effects of this transformation invaded every corner of artistic production. Traces of postwar cultural renewal can be found in the bebop of Parker, Gillespie, Monk, Davis and Powell; the Abstract Expressionism of Pollock, de Kooning, Gottleib, Motherwell, Krasner and Kline; Twombly’s drawings; the projective verse of Olson and the Black Mountain poets; the spontaneous poetics of Kerouac, Ginsberg, Creeley, McClure, and LeRoi Jones; Rauschenberg’s assemblages; the happenings of Kaprow, Oldenberg and Dine; the photography of Robert Frank; the choreography of Cunningham and music of Cage; Malina and Beck’s Living Theatre; the films of Cassavetes, Clarke, Brakhage and Bruce Conner; the free jazz of Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Albert Ayler and Coltrane. Etcetera. The emerging aesthetic common to these and other artists during the 1950s and 1960s was an “all-in-one” model of spontaneous expression: “conception, composition, practice, and performance” as one circular motion or action (Nachmanovitch 1990:6). The cultural attitude expressed in the art of spontaneity was largely determined by a combination of speed, gesture, improvisation and unconscious action. As these new, more urgent forms of personal expression fought to disrupt the status quo of American corporate liberalism and “its techniques of information- and impression-management” (Belgrad 1998:1) spontaneity became not only a guiding formal principle but also a way to absorb, interpret and reshape social phenomena.

In The Culture of Spontaneity Daniel Belgrad claims “A will to explore and record the spontaneous creative act characterized the most significant developments in American art and literature after World War II.” Furthermore, “The social significance of spontaneity can be appreciated only if this aesthetic practice is understood as a crucial site of cultural work” (Belgrad 1998:1). A common ambition to contest mainstream values by circumventing scientific rationality and organizational integration, twin elements of the American technocracy, 3 can be clearly delineated in the avant-garde art of this period. Forgoing pre-planned actions and structures for the energy of the moment and direct experience, these artists pushed spontaneity and improvisation to the center of public consciousness. In this context the boppers speeding experiments can be read as both a retaliation to the cooption of jazz by white musicians, club owners and record executives, as well as a reflection of racial tensions, class conflict and urban expansion, to name a few issues.

The development of free jazz at the turn of the 1960s, arising out of both aesthetic and political necessity, forms an interesting parallel with the emergence of bebop two decades earlier. LeRoi Jones notes, “The period that saw bebop develop, during and after World War II, was a very unstable time for most Americans. There was a need for radical readjustments to the demands of the postwar world. The riots throughout the country appear as directly related to the psychology of that time as the emergence of the “new music” (Jones 1998:210). Coleman’s Free Jazz, released in 1961, was paradigmatic for breaking from the traditional jazz structure of a stated theme followed by individual solos; and for expanding the intimate group size – usually four or five – particular to most bebop and post-bop jazz combos. Free jazz (also referred to as “the new music,” “the new thing” and “The New Black Music”) is characterized by collective, rather than solo improvisation; a more explosive force of emotion; increased atonality; free rhythm; and liberation from the regimen of bar measures and time signatures. Although the term “free jazz” refers to a form in which all conventional pre-planning is supposedly set aside, black writers and jazz critics quickly adopted it as a metaphor for the black situation. 4 In the language of 1960s social philosophy, harmonic freedom for jazz equated to symbolic freedom for African-American citizens.

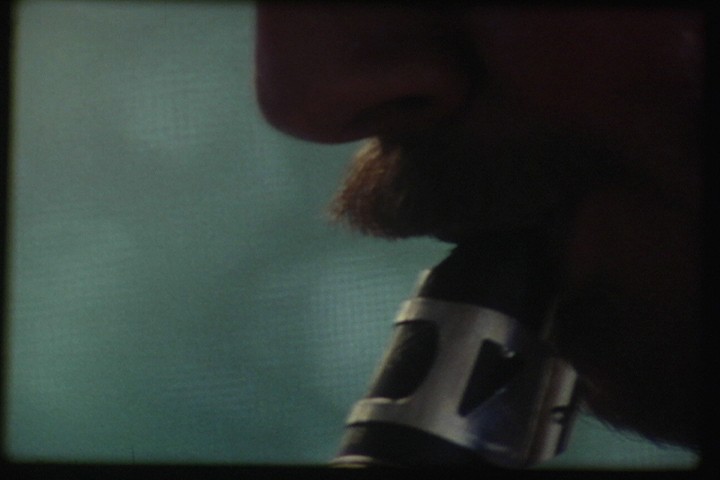

Michael Zerang

in Whoever Fights Monsters

Radical content requires radical form. “Form fascinates when one no longer has the force to understand force from within itself. That is, to create” (Derrida 1978:4-5). Today’s free-form jazz sounds as exciting, chaotic and otherworldly as it did forty years ago… but what does it express about our current environment? Its political imperative – taken for given in the supercharged, desegregated postwar moment¬ – is now less defined, but the underlying spirit of cultural agitation, non-conformity and freethinking remain. Just as new music requires new listening (see below), contemporary concerns require new vision (radical aesthetics, actions). Today’s practitioners of free improvisation have absorbed and internalised the primary sociopolitical vigilance and necessity of 60s free jazz. As one of the musicians in the film, Ras Moshe asserts, “We’re exercising what’s inside ourselves.” Divorced from the precise denotative relationship to civil rights struggle and Black Nationalism, the music’s urgency, passion and revolutionary nature remains: newly rendered spontaneous sonic impulses that reflect the chaos, and reject the conformity of our present (war-riddled) situation. The message I take from it – where the music takes me – is to resist at all costs the safe, the expected. To live at the edge of failure, to exist outside of mainstream taxonomy, to play on the social margins, to forsake technocratic integration and specialization, is to embrace multiplicity, difference and uncertainty, multidisciplinarity and flow. All of these latter preferences embody the open-ended, undone nature of live performance, the flip side of closure, finality, mastery and control.

“New music: new listening. Not an attempt to understand something that is being said, for, if something were being said, the sounds would be given the shape of words. Just an attention to the activity of sound” (Cage 1966:10). How does one mediate the open, performative spontaneity of jazz in a closed, mediated film? In the end, Whoever Fights Monsters is less a free-form jazz documentary as it is a personal exposition on the challenge of registering improvised music’s vicissitudes and vagaries on film. Caught between two impulses (documenting/analyzing and experimenting/creating) Whoever Fights Monsters proves more than a fan’s monument (Tebo is himself a musical improviser). With its loose, liberated structure, circular development and asynchronous approach to sound-image enjambment, Monsters affords an original form and a new model for living out of audio/visual sync. By doing so, the film achieves something remarkable: it enables us to observe the way we hear the world differently.

____________

Sources Cited:

Corbett, John. (1995). Ephemera Underscored: Writing about Free Improvisation. Jazz Among the Discourses, ed. Krin Gabbard. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 217-240.

Belgrad, Daniel. (1998). The Culture of Spontaneity: Improvisation and the Arts in Postwar America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cage, John. (1966). Experimental Music. Silence: Lectures and Writings by John Cage. Cambridge, MA: The M.I.T. Press, 7-12.

Derrida, Jacques. (1978). Writing and Difference. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hebdige, Dick. (2001 Winter). Even Unto Death: Improvisation, Edging and Enframement. Critical Inquiry 27, 2, 333-353.

Jones, LeRoi. (1998). Black Music. New York: Morrow. Reprinted New York: Da Capo, 1998.

Lhamon, Jr., W.T. (1990). Deliberate Speed: The Origins of a Cultural Style in the American 1950s. Washington: Smithsonian Institute Press.

Nachmanovitch, Stephen. (1990). Free Play: Improvisation in Art and Life. Los Angeles: Tarcher.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. (1968). Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future. Basic Writings of Nietzsche, trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Modern Library. Originally published as Jenseits von Gut und Böse, 1891.

Tebo, Ryan. (2006). “The Abyss Looks Into You.” MFA Thesis. New York: Syracuse University.

Author Bio:

Having grown up playing hockey on the Canadian prairies, filmmaker Brett Kashmere now lives in Central New York and writes extensively about avant-garde cinema, music and video, curates international exhibitions, and teaches experimental film.

Kashmere has presented screenings and curated exhibitions at festivals and venues such as the Seoul Film Festival, the D.U.M.B.O. Arts Festival, Cinematheque Ontario, Eyebeam, Cinema Project, Images Festival, and Cinematheque québecoise.

His own work has screened internationally at the London Film Festival, Made in Video: International Video Art Festival in Copenhagen, New York’s Anthology Film Archives, and the Kassel Documentary Film & Video Festival, Germany.

For more information, visit: http://www.brettkashmere.com.

PDF Downloads

- Free Associating Around Whoever Fights Monsters by Brett Kashmere

- The Gates are the least abstruse locational marker in Whoever Fights Monsters, all of which correspond to the musicians’ cities of residence. The former site of Stockholm’s Golden Circle, once an essential European jazz venue (now a family restaurant), and the Chicago River, dyed green for St. Patrick’s Day but shot in shimmering, nondescript close-up, are the others. ↩

- Shadows was scored by Charles Mingus; New York Eye and Ear Control features music by Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, John Tchicai, Roswell Rudd, Gary Peacock and Sonny Murray recorded specifically for the film; The Connection, a feature-length mock documentary about low-life junkies waiting to score, features real-life jazz artists Jackie McLean and Freddie Redd, who composed the film’s soundtrack; while Catalog employs music by Ornette Coleman. ↩

- Theodore Roszak defines the “technocracy” as “that society in which those who govern justify themselves by appeal to technical experts who, in turn, justify themselves by appeal to scientific forms of knowledge” (8). See Roszak, The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and Its Youthful Opposition (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1968). ↩

- See especially Jones, Black Music; Ben Sidran, Black Talk (New York: Da Capo, 1971); Frank Kofsky, Black Nationalism and the Revolution in Music (New York: Pathfinder, 1970). ↩

Notes