The effects of Kabuki on Akira Kurosawa’s Auteurism, Part 1

Introduction and Background

Abstract

The idea behind this research, sub-divided across these two essays, is derived from establishing the connection between kabuki, one of the principal forms of Japanese theatre, and Akira Kurosawa’s period drama films. Kurosawa is recognised by many Japanese scholars and Westerners alike as an auteur. The intriguing point which I discovered during the research was that although Kurosawa dislikes kabuki, his cinematic texts are influenced by its conventions. The reason for this ambiguity is not farfetched, for kabuki heavily influenced the Japanese cinema. Kurosawa, as a studio director, follows the general rules of kabuki, but in order to preserve his personal style, utilises kabuki elements modulated and tailored to suit his subjective inclination.

Introduction: Focus and significance of the study

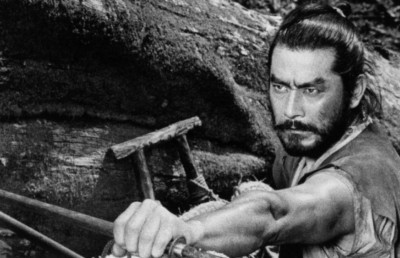

Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998) epitomises Japanese cinema for many Western film scholars over the last half-century. Some of the books on Kurosawa’s oeuvre focus on the link between Kurosawa and auteurism. However, hitherto, none of these books examined this link by studying the influence of kabuki as a form of Japanese classic theatre on Kurosawa’s films, or the extent to which Kurosawa permits his works to be influenced by kabuki’s conventions. Indeed there have been attempts to illustrate kabuki characteristics of Kurosawa’s film for aesthetics reasons; this notwithstanding, they did not consider it as an aspect of Kurosawa’s auteurism. I found during my research that Kurosawa personally did not like kabuki; indeed, he was sceptical towards the concept and did his best to separate his works from kabuki conventions. The problem is that kabuki, as one the most influential sources on the Japanese cinema, leaves a limited space for Kurosawa to preserve his personal style. I hope this text helps readers to reconceptualise Kurosawa’s auteurism and rethink the way that he treated kabuki conventions while making his films.

Methodology

There are a multitude of discussions and debates on auteur theory; however, one of the fundamental similarities in different understandings of the notion is that each auteur has his personal motifs, which can be seen as a directorial signature in his or her films. Kurosawa a director considered to be an auteur by many scholars, thus there are aspects of his films that make a cinematic text a Kurosawa film. The objective of this research is to develop an innovative argument on Kurosawa’s auteurism, and investigate if he utilises kabuki’s conventions in his directing style, and if so, in what way he engages with those conventions.

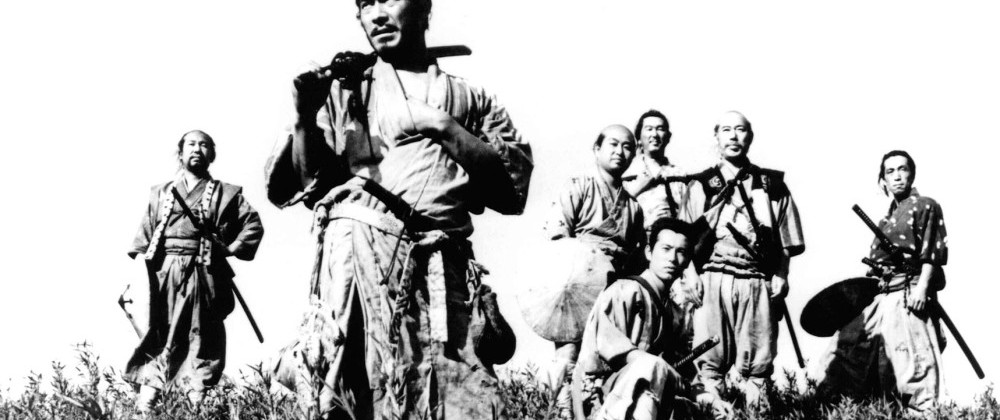

In order to research the above areas, I will analyse one of Kurosawa’s films: Tora no o wo fumu otoko (1945). The English translation is The men who tread on the tiger’s tail or The men who step on the tiger’s tail. Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto’s book Kurosawa: film studies and Japanese cinema contains a chapter on this film, which will be the primary source for the research discussion; in addition, Donald Richie’s books will function as supporting academic texts to create a more in-depth argument and debate on the matter. Furthermore, Keiko I. McDonald’s book Japanese Classical Theatre in Films (1994) will provide extra information for the case study on The men who tread on the tiger’s tail.

The chosen film is by no means the magnum opus of Kurosawa or his sole work with elements adopted from kabuki. [1] He has created other cinematic texts which are influenced by kabuki; however, three significant points make this film a suitable case for academic research:

1. The film is based on the play Kanijincho. Yoshimoto (2000, p.107) describes this play as one of Kabuki Juhachiban, which means it is one of eighteen favourite kabuki plays, from an artistic perspective.

2. Kurosawa added two new characters to the plot. The most controversial one is a porter, played by the comedian Kenichi Enomoto (1904-1970), known as Enoken in Japan. According to Richie (2005), the result of this change was the ‘total alteration of the concept of drama’ in Japanese cinema.

3. This film was banned until 1952. At first by Japanese censors, because it was ‘too democratic,’ and in post-war Japan by American authorities, for being ‘too feudal, too Japanese’ (2005, p.168); therefore, this film can be seen as a controversial case that merits scrutiny.

Reviewing Auteurism

There is a substantial amount of literature dedicated to Kurosawa’s career. One of the early writings by a Western critic on Kurosawa is Noël Burch’s To the distant observer (1979). Burch, whilst describing Japanese cinema as presentational (meaning that there is no attempt to disguise the mechanics of the art, in opposition to representational), distinguishes Kurosawa’s filmmaking style from the typical mode of Japanese cinema by claiming that Kurosawa created a personal representational cinema based on the Western tradition of filmmaking. Burch’s reasoning here is that a Kurosawa cinematic text is merely a Western film with a Japanese façade. Burch is not the sole Western writer with this idea; in fact, other Western scholars, most notably Donald Richie, consent with this argument on the presentational nature of Japanese cinema. However, Richie, in two of his books, The films of Akira Kurosawa (1984) and A hundred years of Japanese cinema (2005), presents an innovative perspective on the Japanese identity of Kurosawa’s works, which controverts Burch’s ideas. Richie tries to establish Kurosawa as an auteur who represents his Japanese mentality and identity through film. Kurosawa: film studies and Japanese cinema by Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto (2000) takes a similar critical approach towards Burch’s ideas; nevertheless, Yoshimoto is more critical of Burch’s ideas than Richie. He tries to clarify that not only is Kurosawa an auteur of representational cinema, but he also follows the traditional rules of Japanese cinema. That is, Japanese cinema is not presentational as Burch or his promoters suggest, but representational.

In order to study the auteur theory in depth, in addition to Yoshimoto’s book, two other written texts including Theories of Authorship (1981) edited by John Caughie and Auteur and Authorship (2008) edited by Barry Keith Grant have been studied. These books include many (if not all) of the key texts that have been written on auteur theory, since its conception in the early 1950s. I chose these books because they help the reader to learn more about the developments of the theory, and the positions which this research will reference and rely on. Besides these books, Peter Wollen’s Signs and meaning in the cinema (1972), and Roland Barthes’ Image, music, text (1977) will provide additional discussion for the literature review. The final books that I used in writing the literature review are Akira Kurosawa’s Something like an autobiography (1983), and Carl Gustav Jung’s reprint of Dreams (2002). Kurosawa’s account of his early years as a film director is a helpful source for readers to understand his mentality and vision, and why he is considered to be an auteur.

Peter Wollen (1972) observes the foundations of auteurism in connection with the political conditions of France in the Second World War. The Vichy government (1940-1944), under occupation by Nazi Germany, was ruling the country at the time. The result was harsh interdiction on different aspects of social, political and cultural freedom. The hegemony of these two political systems practised its authority through actions such as banning Hollywood films. As is common, severe censorship often builds cultural curiosity in the masses. After France’s liberation, many American films were imported. The great appetite for Hollywood films, coupled with their sudden and newfound freedom, resulted in an excessive emotional impact on French audiences.

The high degree of attention paid by the audience required a new approach to the American films. Wollen (1972, p.74) believes, “[auteur theory] sprang from the conviction that American cinema was worth studying in depth, that masterpieces were made […] by a whole range of auteurs, whose works had previously been dismissed and consigned to oblivion.” As with any new theory, auteurism condemned the ways of the past, and offered redemption for the future. Cahiers du Cinéma [2] and its young critics [3] undertook this task. As one of the pioneers of the movement, François Truffaut, in his inspiring essay “A certain tendency of French cinema” (“Une certaine tendance du cinéma Français,” January 1954) cited in Grant (2008, p.9), argues that in the French cinema of the time there was nothing but a handful of films per year, with no artistic quality worth mentioning. He sarcastically labels the directors of these films as “followers of tradition of quality.” By quality, Truffaut did not refer to artistic values, but rather, over-the-top sets, costumes and aristocratic atmosphere in films borrowed from French literary traditions of the nineteenth century. [4]

Auteurism as a notable theory in film studies creates a site for academic debates and intellectual writings. The theory, initially, did not contain a cinematic nature. Edward Buscombe (in Caughie 1981, p.22) writes, “the auteur theory was never, in itself, a theory of the cinema, though its originators did not claim that it was.” The writers of Cahiers du Cinéma always spoke of “La Politique des Auteurs.” One of the early attempts of the theory was to discuss works of Hollywood directors such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock and others in a scholarly tradition. However, this policy soon turned out to be more of an obsession rather than a scholarly crusade. Grant (2008, p.20) mentions that André Bazin in his 1957 essay “De la Politique des Auteurs,” criticises the young writers of the Cahiers by writing, “they always see in their favourite directors the manifestation of the same specific qualities.” There are two points in Bazin’s idea: ‘favouritism among directors’ and ‘specific qualities.’ The latter constrains cinema and deviates it from a secular concept to a series of dogmatic codes, i.e. how to make a good film. The former creates an atmosphere of discrimination and stigma towards non-auteur directors. The ‘Politique des Auteurs,’ despite its lack of perfection and clarity, survived and even flourished.

It was Andrew Sarris who for the first time used the term ‘auteur theory’ in his 1962 essay “Notes on the Auteur theory.” Sarris condemned early critics of the theory; cited in Grant (2008, p.37), he argues: “unfortunately some critics have embraced the auteur theory as a short-cut to film scholarship […] without the necessary research and analysis, the theory can degenerate into the kind of snobbish racket.” It can be reasoned that Sarris is worried about accepting the theory based on some general assumptions without contemplating the details of the concept. In addition, he attacks the idea of ‘specific qualities’ by referring to a relation between how each director, due to his personal mentality and filmmaking style, distinguishes himself from others. This means auteur theory is not a guidebook for young directors for making films, but rather how different directors reflect their individuality in their films.

Andrew Sarris’ ideas contributed to the evolution of the theory, but failed to come up with a perfect definition. Peter Wollen (1972, p.77) writes: “The auteur theory grew up rather haphazardly; it was never elaborated in programmatic terms in a manifesto or collective statement. As a result, it could be interpreted and applied in broad lines.” It can be conjectured that the lack of definite structure takes away the chance of a coherent evolution and jeopardises the future of auteurism.

The next point is that critics and scholars have contrasting views on the theory, with varying definitions. Andrew Sarris in Yoshimoto (2000, p.55) defines what an auteur is as follows: “certain film directors are called auteurs precisely because they overcome economic, cultural and historical constraints and limitations.” It seems that Sarris ignores two important concepts: artistic quality and the term ‘noise’ (elaborated by Wollen). A film can be made in the most difficult of situations conceivable. However, the epithet that saves the film from neglect is artistic quality. This concept applies to both context (visual aspect) and content (the message of the film). A film with little or no quality in these respects is like a love-less liaison, to be gradually forgotten.

The other issue that Sarris left completely unexplored is ‘noise.’ The idea of ‘noise’ is driven from communication studies. John Fiske (1982, p.8) defines ‘noise’ as “anything that makes the intended signal harder to decode accurately.” The pivotal point is that with noise, directors cannot have all the elements they require. They need to compromise at all levels of filmmaking to pull the film together and encode their messages. According to Wollen (1972), it is impossible for a director to have full control over a film. The problem is hidden in the “concept of noise.” It can be concluded that ‘full control’ does not exist or is hard to achieve, and therefore it cannot be recognised as one of the auteurist trends.

Sarris defines the auteur as a director with a personal vision of the world. Janet Staiger develops the definition of auteur. She suggests that “consistency and coherence of statement” are other characteristics of an auteur. When human beings encounter an original situation, their mind is not altogether helpless; indeed, they benefit from their schemas. [5] According to Aaron Beck (1990, p.4), “Schema provides the instructions to guide the focus, direction, and qualities of daily life and special contingencies.” The ‘personal vision,’ which Staiger speaks about, can be thought about in terms of schemas. Also, ‘the consistency’ that she describes is the disciple to ‘personal vision.’ A human’s ideas are changeable. In fact, they need to change periodically to help the person cope with social changes that happen all the time. In spite of this point, as long as the ‘personal vision’ is not fundamentally changed, the ‘consistency’ would remain untouched.

Many critics support auteurism. Wollen (1972, p.78) places auteur critics into two main schools: “…those who insisted on revealing a core of meanings, of thematic motifs, and those who stressed style and mise en scène.” Wollen expresses his consent for the former opinion by writing: “The work of the auteur has a semantic dimension; the work of the metteur en scène, on the other hand, does not go beyond the realm of performance of transposing into the special complex of cinematic codes” (p.78). It can be surmised that the notion of ‘semantic dimension’ is an attempt to display the auteur as a semiologist who obtains his reputation in deciphering visual codes. Further on, Wollen (1972) emphasises a great deal in the ‘personal structure’ of the auteur. He describes the idea as “a structure which underlies the film and shapes it, gives it a certain pattern of energy cathexis.” Yoshimoto (2000) disagrees with this definition. He argues that Wollen’s mode of auteurism does not explain the ‘reason’ why a certain director has a certain structure in his films. Wollen, by not searching deeply for the ‘reason,’ simply accepts ‘personal structure’ as the product of the unconscious mind.

According to Jung (2002, p.75), “The unconscious, the matrix of dreams, has an independent function.” Jung describes the matter in greater depth, but still leaves it not well-explored. Yoshimoto, on the other hand, seeks explanation elsewhere: in Michel Foucault’s teachings, who writes in Yoshimoto (2000, p.58), “The auteur serves to neutralize the contradictions that are found in a series of texts […] at a particular level of auteur’s thought.” It can be suggested that Foucault and subsequently Yoshimoto try to reason that the auteur, in fact, is a mediator. This vocation causes the auteur unconsciously to isolate his judgment in order to be able to compare different ideas for creating an artistic point. Kant’s teachings can be a sophisticated support for Foucault’s and Yoshimoto’s arguments. According to Kant cited in Jung (2002, p.36) “to comprehend a concept is to cognize it to the extent necessary for our purpose”; the ‘extent necessary’ is the level that an auteur would not allow his ‘personal judgment’ to distort his ‘neutralization.’

The next critical doctrine of auteurism was embodied by Roland Barthes, summarized in his well-known essay from 1968, “Death of the Author” (“La mort de l’auteur”). Barthes (1977, p.142-143) defines auteur as “…a modern figure of our society insofar as, emerging from the middle ages with English empiricism, French rationalism and the personal faith of reformation. It discovered the prestige of the individual.” It can be argued that ‘the death of the auteur’ is like a ‘communist manifesto’ for art. The initial claims of both texts are in condemning the past for paying too much attention to individuals.

Barthes (1977, p.146) expands his ideas by writing: “…a text is not a line of words releasing a single ‘theological’ meaning…but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of meanings, blend and clash.” The redundant meaning of Barthes’ message contains the antithesis between an artistic text and an ecclesial one. There are no dogmatic, unbreakable rules in art as the emancipation of human vision and emotions. On the other hand the entropic meaning of his message is that the text is not original. The reason for this claim can be found in intertextuality. There are endless numbers of texts, and they are all intermixed and consequently affect each other. A text cannot be created without the help of other texts. There are scholars and critics who believe intertextuality is the sign of lack of personal attitude of the artist in creating his or her work. Barthes (1977, p.148) explains intertextuality as follows: “…a text […] is drawn from many cultures and entering into mutual relations of dialogue, […] but there is one place where this multiplicity is focused and place is the reader, not as was hitherto said, the auteur.” Nevertheless, in contrast with this idea, critics like Brian Henderson believe that intertextuality is one of the finest aspects of creating a new artistic text. He writes in Caughie (1981, p.123): “The exact value of a text lies in its integration and destruction of other texts.”

Barthes focuses a great deal on the role of the reader in understanding intertextuality, partly because of his Marxist ideas. After all, from a Marxist point of view, the whole community of people is the reader. The genuine effect of Barthes’ ideas is not the destruction or invalidation of the auteur idea. The function is in portraying the fundamental faults of the concept. It is virtually certain that the auteur theory shows little interest in the subject of a text’s reader. The theory divorces the director of a film from everybody else in the universe, and positions him as an untouchable dictator.

Barthes’ ideas faced some critical debates as well. According to Foucault cited in Yoshimoto (2000, p.59), “the notion of work as a unity implies the presence of the auteur, which prevents the unity of a work from disintegrating into a random collection of texts (novels, letters, contracts, etc.)”. Later on, he continues arguing (2000, p.60): “any unevenness of production is ascribed to changes caused by evolution, maturation, or outside influences. It is the auteur that gives unity and coherence to a body of work.” It can be suggested that Foucault tries to study the subject from an objective view; thus, in his teachings, the auteur is not an impervious heroic figure but a mediator who resolves obstacles, allowing the larger system to run smoothly. In contrast to Barthes, he does not daringly pray for the destruction of the auteur; he knows it can be very damaging to an artistic text. A cinematic text with no auteur is like a garden with no gardener; it goes to waste.

Section II. Akira Kurosawa’s works from an auteurist perspective

Yoshimoto (2000, p.59) writes: “in Kurosawa criticism, auteurism has not been the focus of any extended debate.” The idea he implies is that many Anglo-American scholars and critics like Noël Burch or Donald Richie do not study Kurosawa’s works based on auteur theory’s norms. They confuse the auteur perception with socio-political and historical elements of Kurosawa’s works.

Yoshimoto (2000) writes in-depth about the above discussions in his book and tries to define Kurosawa as an auteur. Yoshimoto believes that there is no general view on the roots of Kurosawa’s filmmaking approach, so he divides the critics and scholars who work on the subject as follows: the first school believes that Kurosawa maintains a very Japanese perspective in his style. He portrays various aspects of different characters in accordance with Japanese cultural views. However, these critics complain that Kurosawa does not have enough mental strength to decipher Japan’s social issues. They reason that this problem arises because of Kurosawa’s great desire for his own isolation. The epiphenomenon is the lack of communication between him and ordinary people. These critics and scholars go so far as to call him ‘Tenno.’ [6] His autobiography is a proper source for responding to these allegations.

Kurosawa (1983, xii) writes: “Jean Renoir said: We do not exist through ourselves but through the environment that shaped us….”; later on, Kurosawa announces his strong agreement with Renoir’s ideas. The first reason for this acceptance is Renoir’s theory on social influences on the lives of humans, inspired by Karl Marx’s doctrines. As young men in the 1920s and 1930s, Renoir and Kurosawa (as was the fashion of the time) showed great sympathy towards Marxist philosophy and were followers. Kurosawa, by predicating his consent to Renoir’s ideas, suggests that even years after the social movements of the 1930s, he agreed with leftist teachings.

The second reason for Kurosawa’s agreement is that he was self-consciously aware of his surrounding society. He accepts the fact that he is only a syntagm of a bigger paradigm. He does not claim to be different from rest of the society. Later on, he writes (1983, p.83) about his constant encounter with people’s difficulties since his childhood and how he suffers for not being “able to help them.” It can be observed in his films how he perpetually goes on about humans’ mentalities and demons in their lives; by doing so, he gives an explanation as to why Japanese society (and on greater scale, human society) constantly suffers from its own wrongdoings.

The next doctrine on the nature of Kurosawa’s works is adapted from Noёl Burch’s teachings. The critics and scholars who are his promoters believe that Kurosawa follows a non-Japanese tradition in filmmaking. Burch, in Yoshimoto (2000, p.2), proclaims: “Kurosawa, after thoroughly assimilating the western mode of representation, went on to build upon it.” Further on, this group of critics continues their argument by idolising Kurosawa as “the most westernized Japanese director” (2000). It is true that in comparison to other famous Japanese directors, Kurosawa focuses less on Japanese customs in his films. Directors like Ozu devote the message of their works solely towards Japanese audiences. On the other hand, Kurosawa has a world-wide view in his cinematic texts. Although Japanese values have a supporting role in his films, this does not mean that his films do not have Japanese roots. Yoshimoto (2000, p.54) suggests, “It is too often the case that critics’ feelings toward Kurosawa as a director are unnecessarily intermixed with their interpretations of his films.” It can be reasoned from Yoshimoto’s ideas that critics conceptualise the nature of Kurosawa’s works as non-Japanese based on personal standpoints. The result of such an act is the narrowcasting of studies on the subject. This might be the reason for Kurosawa’s pessimistic view towards critics. He (1983, p.126) writes: “nothing can be done about critics, but we cannot have such people among film directors.”

Akira Kurosawa (1983) writes that his career in the film industry began by passing the entrance exam of Toho Studios, becoming an assistant director in 1935. [7] He describes the dominant mentality of Japanese studios as old-organisation (director-oriented), and young-organisation (star-oriented). He then claims that he belongs to the former. Nevertheless, he confesses in his short handbook (1975) for young directors about his filmmaking methods that although he is a studio director, “I have never taken a project offered to me by a producer or production company.” This means he always followed his vision in filmmaking and kept his individuality untarnished.

Kurosawa (1983) expresses his personality as a fighter and survivor. He suffered throughout his life from mild epileptic seizures. He overcame the severe censoring of pre-war and post-war Japan. In order to make films, he encountered many constraints. It could be observed, based on Andrew Sarris’ classic definition, that Kurosawa is an auteur. He is also an auteur based on Janet Staiger’s views, because there is a consistency in his films about the authentic nature of human beings’ hearts. This argument does not hypocritically mean Kurosawa is one of the gods with definite originality and no fault. He is fully aware of other texts in his work. He (1975, p.1) describes cinema thusly: “[cinema] resembles so many other arts. It has literary characteristics as well as theatrical qualities.” It can be reasoned that he knows that intertextuality fundamentally affects cinema. These effects can be seen in the structure of his films.

As mentioned above, Kurosawa brings a Japanese mentality to his filmmaking. But what is this mentality and how can it be defined in the case of Japanese cinema? The answer to these questions will be dealt with in part two of this essay, with support from Conrad Schirokauer’s Brief History of Japanese Civilization (1993).

Part two of this essay will begin with a brief history of kabuki theatre and its evolution, i.e. how kabuki, as an artistic product of its own time, survived and developed over time and how this style of theatre motions in parallel with Japanese society and its changes in different epochs of history. Further on, the second part will explore Kurosawa’s personal doctrine on kabuki, and the objective reasons that led him to develop a particular doctrine on kabuki. Benito Ortolani’s book The Japanese theatre: from shamanistic ritual to contemporary pluralism (1990a) will be the main source of information presented in this section.

Part two will conclude with a close reading of The men who step on the tiger’s tail (1945, dir. Akira Kurosawa), and how the director mingles his personal style with kabuki’s conventions through a series of objective and purposeful vicissitudes for making the film fit within his style.

The final point which might arise concerns the purpose of writing about Japanese cinema or films, since I myself have no knowledge of the language, nor extensive knowledge of the culture. In order to answer this critical but objective question, Yoshimoto’s book can be reliable source. He writes:

There is a definite difference in the degree of mediation between a translated Japanese novel and a Japanese film with English subtitles. Whereas in the former almost no aspect of the novel escapes from the effect of translation, in the latter the original sound and image remain intact. This is why it is possible for non–Japanese speaking scholars to watch and study Japanese films in the academic context of film studies and to produce a significant body of scholarly works (2000, p.43).

It should be mentioned that this text is not wholly sufficient, nor is it without its own faults with regards to the subject, although there is a personal hope that the outcome of this research will act as a prologue for more extensive debates.

Endnotes

1 His other films influenced by Kabuki conventions include: Rashomon (1950), Yojimbo (1964), Kagemusha (1980), etc.

2 This famous film magazine has been published since 1951 in France. The founders are André Bazin, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and Joseph- Marie lo Duca.

3 Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol and Jacques Rivette were among the well-known writers of Cahiers.

4 Like the works of writers such as Honore De Balzac and Alexander Dumas.

5 Schemas or schemata are the plural for schema.

6 Yoshimoto (2000, p.380) describes the dual metaphorical meaning of ‘Tenno’ as “the man of power and authority or a man with great distance from his subjects.”Those who criticise Kurosawa refer to the latter meaning of the word. The literary meaning is emperor.

7 Akira Kurosawa worked as assistant director for famous filmmakers, most notably Kajiro Yamamoto (1902- 1974) known as Yama-san.

Bibliography

Barthes, Roland (1977) Image, music, text, London: Harper Collins Publishers.

Beck, Aaron. (1990) Cognitive therapy of personality disorders, New York: Guilford Press.

Caughie, John (1981) Theories of Authorship, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Fiske, John. (1982) Introduction to communication, London: Methuen Publishers.

Grant, Barry Keith (2008) Auteur and Authorship: A Film Reader, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Jung, Carl Gustav (2002) Dreams, London: Routledge.

Kurosawa, Akira (1975) Some Random Notes on Filmmaking, Tokyo: Toho Company Ltd.

Kurosawa, Akira (1983) Something like an autobiography, New York: Vintage Books.

McDonald, Kieko I. (1994) Japanese Classical Theatre, London: Associated University Press.

Ortolani, Benito (1990) The Japanese theatre: from shamanistic ritual to contemporary pluralism, New York: E.J. Brill.

Richie, Donald (1984) The films of Akira Kurosawa, Berkeley: The University of California Press.

Richie, Donald (2005) A hundred years of Japanese Film, Tokyo: Kodansha Publishing.

Sarris, Andrew (1968) The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968, New York: Da Capo Press.

Schirokauer, Conrad. Brief History of Japanese Civilization (1993). Toronto: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning.

Yoshimoto, Mitsuhiro (2000) Kurosawa: film studies and Japanese cinema, Durham, N.C: Duke University Press.

Wollen, Peter (1972) Signs and meaning in the cinema, 3rd Edition, London: Secker and Warburg.