The Work of Hildegard Westerkamp in the Films of Gus Van Sant*

An Interview with the Soundscape Composer (and some added thoughts of my own)

Editor’s Intro:

This piece centers upon a discussion with Hildegard Westerkamp about the use of her soundscape compositions in the films of Gus Van Sant. My questions to her reflect my interest in how her work operates on two simultaneous levels within these films: that of appropriated material originally designed for a non-cinematic context, and that of sound design which could easily be mistaken for material produced especially for these films. The result of this dual-layered positioning is an intriguing hybrid of the effects of a compilation soundtrack and dedicated sound design, and her answers to my questions offer valuable insights into the re-positioning of her work within this context. I then draw on these insights as I examine two important shots from the end of Last Days which I believe are reflective of Van Sant’s “Death” trilogy as a whole. Ultimately my aim here is to illustrate how certain concepts that Westerkamp deals with in her own work are similar to those explored by Van Sant, making his appropriation of her work decidedly appropriate. As such, Van Sant’s engagement with Westerkamp’s work offers a very special example of how films might be designed with sound in mind. -RJ

__________

One of the most common functions of sound design in the cinema is to contextualize the environments presented on screen: the adding of sonic depth to visual surface. In Gus Van Sant’s “Death” trilogy, consisting of Gerry, Elephant and Last Days, he has explored sound’s potential to invert this relationship: what we hear often becomes a surface which frustrates a coherent understanding of the spaces given to us on the image track. In so doing, Van Sant has meticulously crafted a series of films that employ the disenfranchising of sound from conventional relationships to the cinematic image as a foundation for exploring the cultural environment of disenfranchised youth. Much of this is the result of his collaborations with sound designer Leslie Shatz. But there is another figure whose contribution to the latter two of these films is of paramount importance: Canadian soundscape composer Hildegard Westerkamp.

Hildegard Westerkamp

One of the founding members of the World Soundscape Project with R. Murray Schafer, father of acoustic ecology, Westerkamp’s work draws on a long history of interest in soundscape research and the emerging tradition of using field recordings as the basic elements of sound composition. Her work is often concerned with the changing nature of our sonic environments, how they engage with us, and how we engage with them (if at all). Of particular importance to acoustic ecologists is the role of context when considering the individual in relation to her environment, and Westerkamp’s work reflects this. As such her compositions are ideally suited for helping to flesh out Van Sant’s portraits of young people adrift in worlds from which they are seemingly detached, but who might well be pointing towards alternative modes of environmental awareness. These films thus provide a new angle from which to examine the role of de-contextualization as both a practical component of, and thematic element within Westerkamp’s soundscape compositions. In turn, the presence of her work in these films offers a valuable entryway to the examination of Van Sant’s aesthetic and thematic concerns.

There are interesting relationships to be drawn between Van Sant’s use of Westerkamp’s work and the themes of de-contextualization and disengagement that are apparent in these films. Of particular importance is how Westerkamp’s inclusion in the soundtracks to Elephant and Last Days relates to the now familiar category of the compilation soundtrack: the adoption of pre-existing music for use in a film. The concept of the compilation soundtrack poses a fundamental question of ecology: how does the removal of a piece of music from its original context and re-situation within the environment of a film affect the music itself, its point of origin, and the new cinematic world in which it comes to rest? It doesn’t take long to trace permutations of this question throughout the discourse of fidelity that has flourished in the age of mechanical reproduction. And there are some powerful examples to be found in the realm of cinema: Tarantino’s use of “Miserlou” for the opening credits of Pulp Fiction is a high watermark for the fusion of song and film to the point that to think of them separately becomes almost unfathomable. For some people such examples suggest a deplorable situation in which great pieces of music are forced into bastardized associations from which they can rarely be freed. Indeed, many have suggested that the likes of Tarantino should be reprimanded for their arrogant lack of respect in the act of appropriation. Just think of all the legions of ageing surfers who can no longer hear one of the defining tracks of their generation without thinking of John Travolta catching an enormous millennial wave long after he was thought to be washed-up on the shores of his success of decades past. Good for him. But perhaps good for “Miserlou” as well. Times change, cultural associations change, and there is nothing more contemporary than to look to the past to help thread the disparate patches of our postmodern society together. Or so some would say.

Without making a value judgment concerning what makes an appropriate approach to appropriation, I suggest that the use of Hildegard Westerkamp’s work in the films of Gus Van Sant offers an intriguing model for the re-contextualization of existing music within the cinematic environment. The use of her compositions “Beneath the Forest Floor” and “Türen der Wahrnehmung” (“Doors of Perception”) in Elephant and Last Days provides a powerful example of the simultaneous strangeness and familiarity that results from situating existing material in the context of new work. The difference here, compared with the use of pop songs as part of a film’s compilation soundtrack, is that Westerkamp’s soundscape compositions are not pieces of “music” in the conventional sense. Within the films they operate more on the level of “sound effects” than of “music” or “score.” One could easily go through the entirety of these two films and believe that the sounds of Westerkamp’s work were actually elements created by sound designer Leslie Shatz, or perhaps even recorded on location. “Miserlou” will never be thusly mistaken. And yet there is a prevailing sense that when we hear Westerkamp’s work in these films, we are hearing something decidedly unsettling in its appropriate-but-not-quite-perfect bond with the audiovisual elements that surround them. In other words, her pieces point to their origin from outside the film while simultaneously becoming inextricably enmeshed within their new habitats.

The intrigue created by this re-situation of Westerkamp’s work lies somewhere between her compositional intent and Van Sant’s tap into this intent, a tap that brings the substance of her work forth while draining the vessel that once gave it shape. Things get even more interesting when we learn that “Doors of Perception” was originally created for exhibition in a space that Westerkamp had never experienced for herself. As such, a lack of coherent context is inherent to the composition, on the levels of both creation and exhibition. So its first life was lived as a re-contextualiztion that was already out of Westerkamp’s hands from the start, a situation then exacerbated by the work’s transposition into a cinematic environment. Yet it is this second-order re-contextualization that resulted in Westerkamp’s feeling that the piece had finally found a home which it could call its own. It is on this note that my conversation with her begins.

R.J. When we talked briefly two summers ago you mentioned that upon completion of “Doors of Perception” you were somewhat unsatisfied with the way it turned out. But when you saw Elephant all these years later, and heard how it was incorporated into the sound design, you felt as though this film is what it had always been intended for, that “the excerpts of the piece used suddenly had a context that made sense.” What was it that you felt didn’t sit properly in the piece as originally conceived? What were you trying to accomplish, and what aspects of it didn’t work? What is it about the film that makes the piece work in a way that it failed to do on its own?

H.W. When I composed the piece I was composing for a specific context: outdoor locations like bus stops, public entrance ways, etc. in Linz, Austria during one of the first Ars Acoustica festivals there. These locations were described to me by the commissioners of the piece, ORF (Austrian Radio), but I did not know them from personal experience. I had never been in Linz, plus I never got any feedback on how the finished piece ended up sounding in its locations. I chose the idea of ““Doors of Perception”” because it gave me a freedom – in this unfamiliar arena where I had to imagine the spaces for which I composed – of moving sonically into all sorts of different spaces through the literal use of the door sound. To feel a little more connected to the location, I had asked them to send me some sounds from Linz, which do appear at the beginning of the piece. I also used some other European soundscapes that we had in the collection of the World Soundscape Project’s archives. But the simple fact that I never experienced the piece in the place for which it was intended disconnected me from it. Its use in Elephant reconnected me to it, but in a totally unexpected way. The fact that Gus van Sant and Leslie Shatz picked the piece and applied it to their context, and made it work, delighted me!

R.J. Your compositions are clearly not devoid of structural organization and work very well when heard as uninterrupted wholes. When they appear in excerpted form in these films, do you think they suffer? Or do they, perhaps, benefit from some structural reorganization within the films? Can you comment on any ideas you have about the ways in which your work has been changed to suit these films?

H.W. I do not think my pieces suffer from this use – at least I do not perceive it that way. The cinematic context is so different and is as much its own thing as my pieces are. And I think that is precisely why it works. The excerpts were applied in the film with a very sensitive compositional ear in conjunction with all the other sounds in the film, i.e. within its own strong context, so that they take on a life of their own – quite apart from, and without destroying, how they exist in the original composition. I am fascinated by how someone else with a sensitive ear can take my work and apply it in a place where I would never have thought of putting it! I know I would react very differently if my work had been applied thoughtlessly and superficially. But this has not been the case here. I feel lucky in that regard.

R.J. I’m interested in the relationship between the tone inherent to your work, and how this might fit, and/or be altered by, the way that Van Sant and Shatz use it in these films. You once mentioned that the use of “Beneath the Forest Floor” in Elephant tapped into the darkness underlying that piece. Can you talk a little bit about this idea of darkness as you had originally envisioned it for the piece? And how do you think this idea of darkness translates into the subject matter and/or tone of the film?

H.W. The darkness was quite unintended when I was composing the piece originally. It simply emerged as I worked with the materials and it began to make sense. The title “Beneath the Forest Floor” emerged out of what I began to hear in the piece while working on it. I think Gus and Leslie simply heard that darkness (without knowing or being attached to my ‘story’ or context) and could apply it to the worst moment in the film, right after the first shootings. The inherent tension of peace/silence and darkness in the piece works perfectly well for that dramatic, horrible moment! I would have never been able to use it in that moment myself, had I been the designer, as I am too close to my own concepts and ideas. But they were distanced from those and could easily use it. Luckily they did it tastefully and in a non-sensational way.

R.J. This distance between the filmmakers and your work does indeed seem important to how they were able to make use of your compositions in contexts that you wouldn’t have imagined. My sense is that part of the success of the sense of alienation that they achieve in these films, with respect to characters within their environments as well as for the audience in relation to the films themselves, comes from the re-contextualization of these compositions through a certain measure of distance from the material. I’m interested in how this alienation might relate to the motif of walking which is very strong in Elephant, as well as Gerry and Last Days. I know that soundwalking is a major premise underlying many of your works. Soundwalks are usually associated with an interest in becoming more aware of one’s environment, with a process of contextualization and familiarization. Yet when your pieces appear in Elephant, for example, they seem more related to a de-familiarization of the space we see on screen.

So, I have three questions relating to this issue. Firstly, can you comment on how the idea of the soundwalk relates to “Beneath the Forest Floor”, if at all?

H.W. There is no conscious direct connection. But the recording process is of course a movement through the forest space, an exploration of the soundscape, a capturing of what is there. There is the type of walking that opens the environment up to us and connects us to our inner selves. That ideally is what a soundwalk is. But a soundwalk does not necessarily mean that we connect directly/socially to the environment through which we walk, as the emphasis is on listening and not on speaking. We may recognize and get to know it better, but we are not responding. However, there is no trace of alienation in this. It is the opposite: it is an openness to the place in which we are letting it in, acknowledging a relationship, but feeling no obligation to respond. And then there is the type of walking through a space that comes from a place of inner desolation/isolation (through empty institutional corridors and wide open suburban spaces in Elephant) or disconnect (through natural environments or even into the town/social environment in Last Days), where there is no connection to the environment other than perhaps a few not very meaningful meetings with people. In this walking situation the senses are not open to the place in which one walks. The place has no power to enter one’s inner world, there is no relationship, no dialogue.

R.J. Second, what do you make of the presence of extended walking shots in van Sant’s films?

H.W. The presence of extended walking shots in Van Sant’s films is a brilliant way of connecting inner worlds between the people on the screen and us viewers. The close-up shots of a person moving, sometimes only the head from the back, together with the accompanying sounds/soundscapes, create that inner connectedness from viewer to person on screen. I find the establishment of this connection less successful in Last Days, perhaps because the characters are too culturally alien to me. The film took me back a bit too much to the days of when I first arrived in Vancouver as a very straight young immigrant from Germany (1968) and could not make head or tails out of the stoned ‘vibes’ that surrounded me. But the fact that my soundscapes work extremely well with this film is perhaps precisely because of the cultural ‘otherness’ of the sounds – sounds that would in fact be quite alien to the main character. But I am only guessing here, as I’m still puzzled about the fact that my piece works so horribly well in the film!

R.J. Finally, do you see any correlation between Van Sant’s interest in walking and your own?

H.W. Only in the sense that we all know both ways of walking as described above and whatever variations of the two are in between these extremes. Since the environment is present in both types of walking scenarios, as a type of sounding witness, no matter whether we notice it or not, the use of environmental sounds in Van Sant’s films plays a similar but heightened (more consciously applied and designed) accompanying role to the visuals.

_____

As Westerkamp’s comments suggest, the variations between the extremes of engagement and alienation within the environments that Van Sant’s characters inhabit creates the very particular relationship that these films enable with their audiences. It is easy to attack the “Death” trilogy as offering little in the way of psychological motivation for that which the characters enact onscreen. Yet their actions are there, and we are placed in the position of being either open to engagement or maintaining a position of distance. The appearance of Westerkamp’s compositions in the latter two films of the trilogy operates in much the same way: her work can be heard as sitting upon the surface of Van Sant’s worlds, hovering somewhere in the ether; or they can be heard as material which reaches through this ether and touches the earth, healing the breach between engagement and alienation by demonstrating how something as simple as a shift in our attention can position us deep within the ecology of these films. So it is for Van Sant’s characters as well.

Near the end of Last Days, there is a single shot lasting three and a half minutes in which Blake is shown wandering along the driveway of his estate, approaching and then entering the greenhouse in which he will be found dead the next morning. In addition to the sound of his own footsteps and unintelligible mumbling, for the duration of this shot we also hear an unaltered section of “Doors of Perception” involving trickling water, chimes, doors banging, orchestral music playing, someone whistling, and reverberant footfalls on a hard interior surface. 1 Most of what is heard here seems incongruous with the image of Blake walking in the environment pictured on screen, and thus the bulk of these sounds appear to be coming from somewhere else. Yet just before entering the greenhouse he suddenly turns to look over his shoulder as though reacting to something heard from behind. This is a moment where the sounds of Westerkamp’s piece might be said to enter the realm of Blake’s awareness for the first time, indicating a point of connection between his individuality and the larger context of the environment in which he is moving. So we might understand this moment as a shift between the closed and open models of environmental engagement that Westerkamp identifies above. In choosing to read Blake’s reactions this way, we can come closer to accessing the significance of his death shortly thereafter.

It is of great importance that Blake’s first reaction occurs just after we hear an orchestra begin a phrase which is completed by a lone whistler. In fact, he turns to look behind him just after the first note of the whistler’s phrase has sounded, as though it were this whistler that has caught his attention amidst a sea of floating noises. The shift from orchestra to lone whistler is a move from macrocosm to microcosm, a call to shift from the ether to the earth. Like the whistler’s engagement with the orchestra, Blake has adjusted his attention to become aware of his own larger environment. This adjustment reflects an essential aesthetic and thematic model upon which these films are based, and which is also inherent to Westerkamp’s work: the constant negotiation between the very small and the very large, between the personal and the larger context in which the individual exists.

After his reaction to something that ultimately remains unseen, the shot continues with a series of actions which gain significance when considered in relation to the sounds we hear from Westerkamp’s piece: Blake approaches the greenhouse, reaches for the doorknob, turns the handle, opens the door, enters the room, sits down, and then looks around until suddenly locking onto something we don’t see, finally holding that position until the shot ends. As he turns the handle, opens the door, and moves into the greenhouse, we hear an equivalent series of sounds appropriately synchronized: a door latch being turned, some related creaking and banging, and a subsequent shift in ambient sound that reflects a move from one space to the next. In fact, most of the sounds we hear as Blake moves from outside to inside are taken from “Doors of Perception” (with just a couple of additions provided by Leslie Shatz). The precise point of synchronization between the image of Blake opening the door and the equivalent sounds from Westerkamp’s piece suggests without a doubt that this soundscape excerpt has been positioned in such a way that Blake’s move into the greenhouse becomes the point at which Westerkamp’s piece makes contact with the physical plane of Blake’s environment. His prior reaction to the unseen whistler can therefore be understood as a harbinger of the inevitable concretization of “Doors of Perception” within the physical environment that surrounds him. The sound of the door becomes a symbol of Blake’s own shift in perception.

Finally he sits down, staring into a void while appearing to be listening intently to the chorus of church bells that are now audible in Westerkamp’s piece. Again it is no coincidence that he becomes transfixed at precisely the moment that the bells appear on the soundtrack, indicating once again that his actions throughout this shot have been synchronized to the excerpt from “Doors of Perception” that has been responsible for most of what has been heard. The bells seem at once distant and impossibly close, suggesting a merge between different planes of experience, allowing Blake to make contact with an environment that has remained otherwise elusive. At long last he now seems engaged with an impossible soundscape that is, nevertheless, the one in which he has been living. The separation between himself and his surroundings has collapsed. He is finally ready to return to that from which he came (regardless of whether it is by his own hand or through that of another), a transcendence of the body that is inherently ecological in its acknowledgment of the relationship between life as he knows it, that which came before, and that which awaits him afterward.

I suggest that it is towards Blake’s emergence from alienation that Van Sant’s entire “Death” trilogy points. The use of Westerkamp’s work in the context of these films, remaining firmly rooted within the worlds that play out on screen while extending outward to realms that lie beyond, might also be a cue to read her work as a point of entry to the spirit of Van Sant’s characters; that which might keep us at a distance from these films is that which might also allow us access to their profound depth. Just as a soundwalker can shift from alienation to engagement within a foreign environment, so too do Blake’s final moments demonstrate a change in his state of mind. Perhaps this change suggests the logical conclusion of his extreme alienation which, when its peak is reached, turns inside out and opens him up to the world.

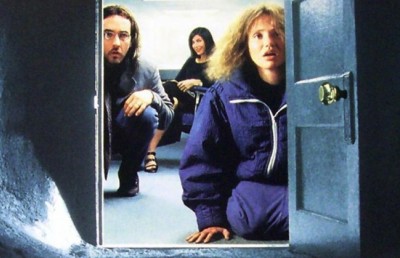

A short while later Blake is shown one last time. In the film’s climactic shot – significantly the only superimposition found in the entire trilogy – his naked body is seen climbing out of the frame to a point unknown while his corpse remains behind. In this shot Blake is at once transcendent and grounded, a fact reflected by his existence on two planes of the film’s surface being presented as one, their separation distinguishable only due to his ghostly translucence while rising from the body on the floor. This translucence is suggestive of Westerkamp’s auditory equivalent: sounds that merge with Van Sant’s environments, at once seeming a part of these worlds while remaining quite distinct. It is as though Westerkamp’s sounds are housed within the spaces we see on screen, while continually offering a ladder out of the frame to lands that lie beyond. This final shot of Blake thus presents a visual analogy for what I have described as the concretization of Westerkamp’s work within this environment: two distinct planes have been positioned in the same space forging a connection between two worlds that seem simultaneously incongruous and at peace with one another. Our experience of the journey to this moment is, amoung other things, a soundwalk through shifting planes of attention guided by Hildegard Westerkamp. Her soundscape compositions help us enact the changing awareness necessary to enabling an engagement with these films, a process of engagement that has been well respected by Van Sant and Shatz in their appropriation of her work here.

__________

*A shorter version of this article is available in French on Offscreen’s sister site Hors-champ:

Jordan, Randolph. (2007, February). En Contexte: Un Entretien avec Hildegard Westerkamp, trans. Nina Aversano. Hors-champ. http://www.horschamp.qc.ca/article.php3?id_article=251

For more information about Hildegard Westerkamp, visit: http://www.sfu.ca/~westerka/index.html

PDF Downloads

- The Work of Hildegard Westerkamp in the Films of Gus Van Sant by Randolph Jordan

- This excerpt from “Doors of Perception” begins at 9:06 in the version originally released on the Radius #4 compilation in 1995, and re-released as part of the Last Days soundtrack album in 2006. Radius #4: Transmissions From Broadcast Artists. Canada: What Next (WN 0019) 1995; Last Days Soundtrack: A Tribute to Mr. K. Japan: Avex Records (AVCF-22746) 2006. ↩

Notes