The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford: A Study in Melancholia

There are many words that come to mind when describing The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik, 2007): elegiac, haunting, autumnal, and melancholic. I would have to say that The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (subsequently shortened to Jesse) is one of the saddest westerns I have ever seen. Yes there are specific nods to classic westerns of the past (The Searchers, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Days of Heaven, The Great Silence), but there is little of the usual human conflict of the individual versus the community, the hero versus the common folk, the garden versus civilization that you normally find in the expansive excitement of the west’s wide open spaces. It is, if anything, an anti-Western, which is a rare breed among American westerns. The Italians got there first with the classic spaghetti westerns of the mid to late 1960s (the use of the winter setting here recalling Sergio Martino’s classic The Great Silence, 1968), but Jesse nails the coffin shut –quite literally– to any notion, real or imagined, of the West as a place where brave men and women roamed, battles won and lost, industries and communities formed.

What is perhaps most shockingly subverted in Jesse is the notion of the honorable gunfighter/hero whose skills with a gun place him above the common man (or woman) but who uses it judiciously and with a sense of personal code, an ethic. In most classic American westerns (think Stagecoach, Shane, The Gunfighter, My Darling Clementine) the use of might is accorded a moral imperative. The good guy kills out of justified vengeance, self-defense, to right a wrong, uphold a community, or rid the world of an evil soul. And the hero kills with honor, always giving the enemy the right to self-defense. There are no such classic showdowns in Jesse between hero and villain. In every instance of death in Jesse the victim is defenseless and without a gun; and in almost every case (so much so that it can be seen as a pattern and a foreshadowing device of Jesse James’ (Brad Pitt) own death) the assassin shoots his victim in the back. As one government agent tells Robert Ford (Casey Affleck) toward the end of the film when Ford has decided to kill Jesse James himself: “Wait your chance…and do not let him [Jesse James] get behind you.” The classic “A man’s got to do what a man’s got to do” becomes “A man’s got to do what he needs to do to save his hide.”

The film’s depiction of the West as no place for heroes and romantic notions of honor is cemented in the crass disposal of a character’s body (Wood Hite, played by Jeremy Renner). After Hite is shot dead in the back of the head by Robert Ford, Robert and his brother Wilbur (Pat Healy) toss Hite’s nude body into a quickly dug hole in the woods and unceremoniously kick snow into the hole to cover his body. A less dignified burial would be hard to imagine.

Brad Pitt’s depiction of Jesse James as a disturbed, depressive, unstable and unpredictable man is, surprisingly, part of an interesting trend in recent North American cinema. To go a step further, several of the most important (and best) North American films of 2007 featured protagonists who were psychopathic, out and out killers. Think of Javier Badem’s serial killer Anton Chigurh in the Coen brothers No Country For Old Men, Johnny Depp’s Sweeney Todd in Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, and Daniel Day Lewis’ oil tycoon Daniel Plainview in Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood. Five of the most decorated and honored American films of 2007 featured wholly bad protagonists. Has such a thing ever happened before in American cinema? One would be hard pressed to even refer to these characters as anti-heroes, since none are what you would call “noble criminals.” They all kill out of greed, vengeance, power, malice or profit. And for the most part they seem to enjoy the killing.

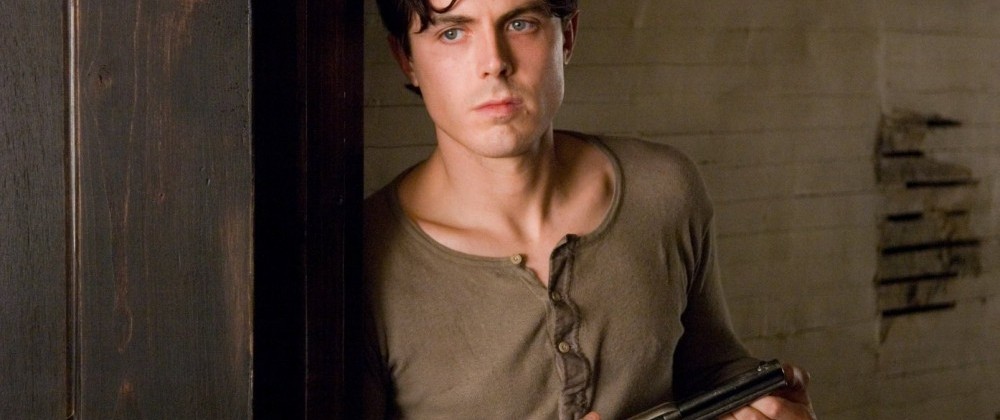

The performances by the two leads (though the film is if anything an ensemble piece), Brad Pitt as the forlorn Jesse James, and Casey Affleck as his assassin Robert Ford, are exemplary. Especially Affleck, in what is one of the most complex Western characters ever depicted on screen. Robert Ford has idolized Jesse James since he was a young boy, and knows more about Jesse than he does himself (recalling the titular Terence Hill character in My Name is Nobody, and his encyclopedic knowledge of the Henry Fonda character, Jack Beauregard). He hides penny novels and comics recounting James’ exploits in a shoe box under his bed. He swoons over him, yet his admiration for him is tempered by delusions of grandeur and an obsessive desire to be famous, something which the film goes to great measure to ruminate on. As Jesse asks him, “Do you want to be like me, or do you want to be me?” Such a character –the young protégé who wants to supplant the reigning king of the gun– has a long history in the Western, from the noted Terence Hill to the Richard Jaeckel character in Henry King’s The Gunfighter. But each has their own peculiarities. For instance, the Hill character from My Name is Nobody wants to orchestrate Jack Beauregard’s mythic status and land him a firmly etched place in history; while the Jaeckel character wants the infamy and status of being the one to kill the most famous of gunslingers, Jimmy Ringo (Gregory Peck). But Ford’s infatuation with James is not to become a famous gunslinger, for he is clearly not cut of that mould. It is a curious mix of jealousy, love, hatred, fear, awe, brotherly affection, and –perhaps– sexual attraction. Whereas the death of the Jimmy Ringo in The Gunfighter and (the feigned) death of Jack Beauregard produce the dreaded cycle, the changing of the guard of the life of one gunslinger (with its glamor and the pain of expectation) replaced by a younger gunslinger who will soon learn what the true pressures of such a life entail.

Jesse begins with a highly stylized, opaque voice-over driven opening which gives viewers an elliptical description of the Jesse James character. Speaking in a cool yet reverent tone, the narrator describes Jesse James (“He was growing into middle age….”) as he is framed in a rocking chair in one shot, framed majestically against a natural landscape of wind blown buckwheat in another, blessed with gorgeously golden magic hour lighting (the film was shot in Alberta, Canada); shots of his body are interspersed with pixilated moving cloud shots; the edges of the frame are given a smeary patina to increase the nostalgic sensibility of the voice-over. In one shot the camera tracks his hand in close-up as it sensually brushes long the wheat stalks (an homage to an identical shot at the beginning of The Gladiator which follows Russell Crowe’s hand…to note that Ridley Scott, director of The Gladiator, is one of the film’s producers).

One could be forgiven if they thought that they were watching a Terrence Malick film after the film’s self-professed poetic prologue. All along a sweetly tinged carrousel-like music by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis recalls one of the motifs from Malick’s Badlands. Keen Malick fans will also spot another reference to Badlands, and the scene where the Sissy Spacek character tosses her dead goldfish away in her backyard. In Jesse we see Jesse James nonchalantly toss two dead snakes –which he brutally decapitated moments earlier– in his backyard. All the individual pieces: the heightened depiction of nature, the voice-over narration, the stylized use of natural lighting, the music, recalls Terrence Malick, yet the film moves away from this after its opening to forge its own style, forceful, quiet, and subdued, like a gentle wind passing through a field.

“He also had a condition that was referred to as granulated eyelids and it caused him to blink more than usual.” (voice-over narrator, voiced by Hugh Ross)

The narrator goes on to tell us that James has a wife, and two children who don’t know him by name, or why they moved around so frequently. He was known in the directory as “Thomas Howard” and went about the town unidentified as a well respected citizen (“a cattle man, a commodities investor, someone rich and leisured, who had the common touch.”) And that “he regretted neither the robberies he committed nor the 17 murders he laid claim to.” The narrator also informs us of some of his standout physical characteristics: a missing knob of his left index finger, incompletely healed bullet holes on his chest and thigh, and the aforementioned eye condition. What is interesting about the latter point is that it draws our attention to his eyes, only to eventually realize that he does not blink more than usual (is the narrator non-reliable?).

At the end of this novel-like prologue the narrator tells us, “And on September, 5, in the year of 1881, he was 34 years old.” The heightened style and reverential visual depiction of James in this opening already casts him as a larger than life character, a mythic figure. This image is no less inflamed in the eyes of an 19 year-old admirer, Robert Ford, who is introduced in the first post-prologue scene gazing intently from a distance at Jesse James seated with his motley gang as they lay in siege waiting for a planned train robbery later that night. Ford makes an appeal to the elder James, Frank (played by Sam Sheppard), to allow him to join the James gang. Frank is unimpressed by the youngster, in fact he is off put by him (“I don’t know what it is about you, but the more you talk, the more you give me the willies.”) Frank sees through Ford’s enthusiasm and illusions of grandeur, but Jesse seems smitten by his adoration enough to let him to join the gang on the train robbery. The voice-over continues to give us a mixture of hard cold fact (“The James gang committed over 25 bank, train and stagecoach robberies between from 1867 to 1881, but except for Frank and James, all the original members were either dead or in jail”) and poetic reflection (“Rooms seemed hotter when he [Jesse James] was in them, rain fell straighter, clocks slowed, sounds amplified….”); the voice-over is also interesting in that it often strips the narrative of any suspense or intrigue by telling us beforehand of events which are to unfold. Of course we know, based on the title (although there too, titles can be deceiving), and on history, that Jesse James will die. But the voice-over tells us exactly when, early on soon after the train robbery when an unsettled Frank James decides to leave the gang for a quiet life (a shoe salesman he says, when asked what he will do for a living). The voice-over tells us: “Alexander Franklin James would be in Baltimore when he would read of the assassination of Jesse James.” The loss of who has seemed the most sensible character in the film, and a clear, positive older brother figure to Jesse is also treated with great melancholy which only adds to the film’s sadness.

The first train robbery, which occurs at about 15 minutes into the film is one of the more impressive train robberies ever committed to film. The lighting and imagery is haunting, with the James gang dressed with burlap sacks over their heads, Jesse framed in silhouette on the train tracks with the blast of the oncoming train’s single light filtered through a heavy fog in the extreme background. A moving shot along the tracks from the train’s point of view frames the gang (who look like KKK members) through the foregrounded sparks of the steel wheels grating along the tracks (producing an abstract image).

The scene, coming as early as it does, is also deceiving, because there are no other such ‘action’ moments in the film. For the balance of the film, that is 145 minutes, there are only two more scenes, totaling about 3 minutes, where gunfire is featured (the haphazard shootout between Wood Hite (Jeremy Renner) and Dick Liddil (Paul Schneider) in a bedroom, which concludes with Robert Ford shooting Hite through the back of his head, and the death of Jesse James). Any viewer expecting like action will be very disappointed by a film which spends most of its time with characters in deep introspection or simply waiting for an event to occur.

James’ most forceful personality trait is a rampant paranoia which is based in reality but magnified ten-fold by his insecurities and pathological behaviour. He suspects everyone, but the film does justify this suspicion by surrounding him with characters who are self-absorbed (Dick Liddil), under his thumb (Ed Miller, played by Garret Dillahunt, and Charlie Ford), or out to arrest him (the law) or profit from his capture in one way or another (Robert Ford). He strikes fear in people because of his unpredictability, best expressed in the scene where he beats up a young boy in an attempt to extort information on the whereabouts of his father, Jim Cummings, and then cries to himself moments later as if in shame or remorse over his action. As if to underscore James’ powerful hold on people around him and his larger than life status, Robert responds to his brother Charlie’s concern that James will intuit their plot to kill him with the refrain, “He’s just a human being.”

In a film oozing with visual sophistication, one of the film’s more interesting stylistic gestures comes in the editing of contemplative images of nature in-between scene changes and/or temporal shifts. (It is never easy to gauge who to credit for such decisions, but the editors of Jesse are Curtiss Clayton and Dylan Tichenor). There are many of these “nature interludes” interspersed throughout the film, many of them coinciding with the voice-over narration: shots of pixilated cloud formations, billowing wheat fields, shards of light entering into empty rooms, etc. These interludes remind me of what Nöel Burch has referred to in reference to Yasujiro Ozu as ‘pillow shots’: shots of empty spaces (without any human element), usually buildings, trains, hallways, objects, streets, etc., which act as a ‘buffer’ between scene or location changes. [1] While in the Ozu context these shots have been interpreted in many different ways –similar to the one-word line that colors the next in classical Japanese poetry, according to Burch, or codas with a semi-Buddhist connotation of ‘emptiness’, nothingness, or silence according to Paul Schrader [2]– in Jesse they seem to act as reaffirmations of the film’s contemplative pace and, from a practical standpoint, allow for ‘listening’ space for the audience during the voice-over narration interludes (like for example, the scene that runs from 62’20” to 62’50”). [3] All this in addition to the previous allusions to Malick and by extension the tradition of American Romanticism which Malick often draws inspiration from. [4] Rather than Ozu, I would say that the use of these ‘empty space intervals’ in Jesse comes by way of Malick. Chris Wisniewski in a discussion of Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven and The New World writes: “the placid images of nature, offering quiet contrast to the evil deeds of men.” [5] This idea of counterpoising acts of violence with contemplative imagery has a direct link to Jesse, rather than Ozu’s domestic/melodramatic use of them.

“There just ain’t no peace when Jesse’s around.” (Charlie Ford, played by Sam Rockwell)

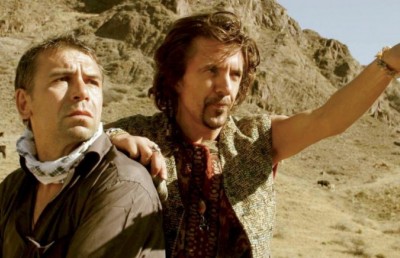

The editing is interesting in other aspects too, like the cutting in the sequence where Jesse pays visits to Ed Miller and Dick Liddil. James first visits Ed Miller, one of the gang members from the opening train robbery, who he suspects is conspiring against him with Jim Cummings (who is talked about but never seen). Throughout their conversation Miller is visibly nervous and terrified for his life. James gets up from his chair and walks over to the open window. The scene cuts to what is possibly a point of view of an overcast sky (though it could also be one of those pillow shots mentioned in the previous paragraph that “[offer quiet] contrast to the evil deeds of men.”). James then asks, “What do you say if we would go for a ride” (a none too disguised code for your time is up). The scene cuts back to the still seated Miller who, in near tears, replies, “OK.” The shot fades to black, then fades back in to Dick Liddil being awoken by a sound in his house which he gets up to investigate. Our first question is, “What happened to Ed Miller?” We can assume that he was shot dead, but this is only confirmed much later in the film when James recounts the incident to Charlie Ford, and we cut to a flashback of James riding behind Ed and shooting him dead from the back. The first thing that James, sitting quietly in the dark kitchen, says to Liddil is “You ready to go for a ride,” forming a suggestive aural link to the previous scene. We then cut to them riding horseback through a forest of bare trees in a fall-like setting, which is followed by a dissolve to a shot of them riding along a wintry, snow-capped clearance (perhaps an homage to the snowy setting during the seven year journey in The Searchers?): a seemingly continuous edit harboring an indeterminate ellipsis based on the seasonal change from fall to winter (hours, days, weeks?). (In the fall shot pictured below we even see James riding behind Dick in the same manner as we will later see in the flashback with Ed.)

The film’s visual style adds tremendously to the sense of sadness hovering over its characters. In terms of lighting and color the film rigorously follows a muted palette which extends to the lighting, which is often represented through dark, overcast skies or an all-white sky which is contrasted by the dark, solid colors worn by the characters and dark colored horses. Hot sunlight does appear but mostly in the opening prologue scene and in some later scenes (namely James’ death scene). Somber or autumnal is the best way to describe the color sphere, which avoids any bright colors and features a dominance of browns, blacks, beiges, tans, and greys. Much of the credit for the film’s visual brilliance goes to cinematographer Roger Deakins (who also lensed No Country For Old Men in an outstanding double achievement in 2007). The art direction supports the muted color spectrum by echoing them in the props, clothes, and interior spaces. I would be remiss if I did not mention the important role the sensitive, touching music by Nick Cave and Warren Ellis plays in generating the film’s autumnal atmosphere.

The assassination scene is a perfect example of all the elements which give the film a somber, autumnal, in fact funereal feel, coming together. The actions of Jesse James, coupled with the use of point of view, suggest that James is in fact well aware of what is about to happen, as if it is his own death wish which is being brought to bear. James very deliberately removes his gun holster and places it out of reach, while standing at the window with his back to Charlie and Robert Ford. A cut to a close-up of Robert seated reveals tears swelling in his eyes and a look of pain and anguish etched in his young face. For this scene the lighting recalls the hot white sunlight of the opening scene, casting a near spiritual sense to the proceedings, with death as a form of welcome release or freedom for Jesse James. This pseudo religious reading is aided by some of the composition, specifically the shot of James framed behind a cross-shaped window, his stiff white color and black vest even giving him the appearance of a minister (even more so in a shot during a later scene in the kitchen where Jesse apologizes to Robert for his erratic behaviour of late, at 118’38”).

All three characters are wearing white shirts and dark brown or black pants or vests. The room is sparsely furnished, with dark brown furniture; the beige walls, which are set-off by a darker ceiling tone, are also sparse, with a simple dark brown wall shelf and portrait on one side and a simple drawing of a brown horse on the other side of the room. James comments, “Don’t that picture look dusty,” in reference to the drawing of the horse, which is oddly positioned high up at ceiling level. It seems hardly likely that anyone could see dust from that far a distance. James sets a chair in front of the wall so he can reach the drawing and climbs it with his back to Charlie and Robert. A point of view of Robert lining up his gun at James is followed by a profile close-up of James who sees in the reflection of the glass pane his imminent death, and does nothing to circumvent it.

In a sequence of rapid cuts, a shot is fired, the force of the bullet sends James’ head crashing against the glass pane of the drawing, and he falls to the ground. His felled body is captured from afar in a distorted, concave glass reflection. It is a fittingly dramatic and stylized end to a figure whose immorality and ruthlessness did nothing to stop Robert Ford from idolizing him, nor from killing him.

This concave reflected glass image represents the death of James, or the end of his natural life, but in a brilliant formal match, a similar reflected image –of James’ corpse being displayed for an official photograph, reflected in the photographer’s camera lens– marks the beginning of his ‘second’ life as a Western icon, a legend, a commodity, a subject for stereoscopes and penny novels, and, one year later in New York city, the subject of a theatrical play starring the ‘real life’ players themselves, Charlie and Robert Ford.

With James dead one would think that the film is over, but director Dominik defies expectation by adding what amounts to a 40 plus minute epilogue charting the effect of Jesse James’ death on Charlie and Robert Ford. In some respects this is the most fascinating part of the film because it adds depth to Robert Ford’s psychologically complex relationship with James and his role in James’ legacy. Robert Ford’s decision to kill Jesse James is more than just a simple act of self-aggrandizement. The point at which Robert has made up his mind to kill Jesse James is presented as a ritualistic display of identity transformation. In this scene, which comes about ten minutes before the assassination, the voice-over recounts Robert’s ritualistic enactment of ‘being in James’ skin’; he sniffs James’ pillow, drinks from his glass, lays in his bed, rubs his chest for the scars James has on that part of his body, etc. It is a bizarre and eerie ritual of a man suffering from delusional self-worth who thinks that blotting out the life of a ‘great’ man will somehow transfer similar characteristics of greatness onto himself. (After he kills James, he sits by James’ holster and caresses his gun.) Will Robert Ford be remembered as James’ assassin? As his assassin, will he be remembered as an even ‘greater’ man? Will he be remembered as James? Will he be remembered at all? All of these questions are answered in the film’s epilogue.

In the scenes following James’ death, Charlie, the dumb brother who stayed loyal to James even when James was plotting to kill him, lived in deep remorse until taking his own life. The shift from a happy-go-lucky Charlie to a morose, suicidal Charlie is striking. Robert becomes an unwilling yet necessary component to the mythologizing of James: the coward who killed a man far greater than he. Robert’s illusions of fame are shattered. When a vaudeville singer he befriends and confides in, Dorothy Evans (Zooey Deschanel), asks him why he killed Jesse James, Robert replies simply, “He was going to kill me.” Then adds, “You know what I expected? Applause….I was surprised by what happened. They didn’t applaud.” In the end, the voice-over reveals Robert’s admission of remorse over killing James, and that “He missed the man as much as anyone.” Rather than fame, he received hate letters, threats, insults and, in an inevitable shade of circular irony, ends up shot dead in the back by a ‘nobody’. To paraphrase the film’s narrator, for Robert Ford there would be no eulogies, no photos, no souvenirs, no biographies….no legacy.

Jesse marks New Zealand born director Andrew Dominik’s second feature after the interesting Chopper (2000), a drama based on the notorious real-life Australian murderer Mark ‘Chopper’ Read, who became a best-selling novelist while in prison. Chopper was played by then unknown actor Eric Bana, who came to the film from the world TV comedy. On the surface there appears to be very little in common between these two films set approximately one hundred years apart (1880s & 1990s). Yet there are several elements Chopper shares with Jesse. For starters, both films are ‘biopics’ based on real life criminals; both leads can be defined as psychopaths and share an uncannily similar body count (the voice-over tells us that Jesse killed 17 men and Chopper is known to have murdered approximately 19 people). Although Chopper has a harsh, realist edge to it, especially its depiction of prison life, and is far more violent than Jesse, it also contains some fantasy moments which show that Dominik is not averse to the type of stylized gesturing which Jesse excels in. Otherwise there is little in Chopper which would have suggested the change in pace and style of Jesse. These two films definitely suggest that Dominik is not afraid to switch gears and makes him a talent to keep an eye on.

Endnotes

1 Nöel Burch. Toward a Distance Observer. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979.

2 Paul Schrader. Transcendental style in film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972.

3 All time codes are according to the DVD.

4 It is also claimed that Malick has had an interest in Buddhism, which would suggest an overlap between his use of these pillow shots and Schrader’s reading of them in Ozu’s films. Films of Being. Accessed May 7, 2008.

5 Chris Wisniewski. “A Stitch in Time Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven and The New World.” Reverse. Accessed May 9, 2008.