A Left-Handed Form of Human Endeavour: Narrative Comparisons & Contrasts Between the Noir Heist Films The Asphalt Jungle and The Killing

“Crime is only a left-handed form of human endeavour.”

Alonzo D. Emmerich (Louis Calhern) in The Asphalt Jungle.

The Noir Heist Film

The Asphalt Jungle (John Huston, 1950) and The Killing (Stanley Kubrick, 1956) can be described as noir heist films. Both films involve a group of nefarious characters and their involvement in an ill-fated robbery. The Asphalt Jungle focuses on a million-dollar jewellery robbery at a bank, while The Killing depicts a daring robbery at a racetrack. However, where these two heist films differ markedly is in their use of narrative structure. The Asphalt Jungle could be considered a textbook example of a classical Hollywood narrative. It has a linear narrative structure and is told in straightforward chronological order. In contrast, The Killing challenges some of these classical narrative conventions by re-working them in an unconventional way, specifically with its use of a non-linear time structure.

In the 1940s and 1950s, stories involving a “heist” theme began to develop in noir films. For example, meticulously staged robberies coincide with stories of betrayal in noir films like The Killers (Robert Siodmak, 1946), White Heat (Raoul Walsh, 1949) and Criss Cross (Robert Siodmak, 1949). A central element in these films is the undertaking of a single crime of great monetary significance (For example, the payroll robbery at a hat company in The Killers, the chemical payroll robbery in White Heat and the armoured car robbery in Criss Cross). Moreover, the story invariably revolves around a group of criminals who plan and execute a clever, daring, but ultimately unsuccessful robbery involving cash or jewels. Often the criminals have a falling out, or make one fatal error that ultimately leads to their arrest.

However, with the release of The Asphalt Jungle in 1950, it can be argued that the focus on the planning and execution of a big heist really emerged as an identifiable theme in noir films. The Asphalt Jungle depicts in great detail how a meticulously planned and executed jewellery robbery, followed by a combination of greed and corruption, as well as the inexplicable element of fate, conspire to bring about the psychological disintegration of the protagonists involved, with disastrous results.

Significantly, the emphasis on the psychological interplay between the characters in The Asphalt Jungle is also apparent in The Killing (In addition, it is interesting to note that both films star Sterling Hayden). Moreover, The Asphalt Jungle and The Killing are similar in that both films focus on a group of criminals who plan, execute and ultimately fail in their attempt to carry out a robbery. But, as mentioned above, it is in their narrative structure that both films differ considerably.

The Asphalt Jungle: The Quintessential Noir Heist Film

When The Asphalt Jungle was released, MGM head Louis B. Mayer was heard to remark caustically, “I wouldn’t walk across the room to see a thing like that.” Thankfully, not everyone agreed with Mayer and The Asphalt Jungle proved to be a major box office hit for MGM [1]. A brooding and atmospheric story that focuses on a failed jewellery robbery, The Asphalt Jungle is the quintessential noir heist film. A benchmark for every American heist film that was to follow (including The Killing), the influence of The Asphalt Jungle was also profound in Europe. [2] For example, Rififi (Jules Dassin, 1955) is a much-admired French noir film that focuses on the robbery of a jewellery store. In Rififi, the pivotal robbery scene, which runs for nearly thirty minutes, is completely silent and contains neither dialogue nor music. This scene is strongly reminiscent of the famous jewellery robbery scene in The Asphalt Jungle. More recently, the influence of The Asphalt Jungle can also be detected in heist-gone-wrong films like Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992).

As mentioned above, The Asphalt Jungle centres on a million-dollar jewel robbery at a bank, which is masterminded by “Doc” Ewin Reidenschneider (Sam Jaffe). Alonzo D. Emmerich (Louis Calhern) is a sleazy lawyer who agrees to fence the jewels (also look out for Marilyn Monroe in one of her earliest roles, playing Emmerich’s mistress Angela Phinlay). The Asphalt Jungle proceeds in an understated way, the story unfolding in straightforward chronological order, with the jewellery robbery occurring mid-way through the film. The narrative is essentially divided into three parts: the planning of the heist, the execution of the heist and the aftermath of the heist. Moreover, the finely detailed performances in The Asphalt Jungle are uniformly superb. Each character has a real identity and is not merely a “stereotype”. Director John Huston expertly combines documentary style realism with controlled and economical studio techniques to create a bleak and cold portrait of the criminal underbelly of American society. In addition, Harold Rosson’s clever and striking cinematography recalls the work of depression-era still photographs. In The Asphalt Jungle, the characters are all doomed from the outset. However, once the wheels of the heist are set in motion, there is no turning back.

The Asphalt Jungle was written by W.R. Burnett, who had also penned Little Caesar (Mervyn LeRoy, 1930) and High Sierra (Raoul Walsh, 1941), the latter being scripted by John Huston. [3] Adapting W.R. Burnett’s novel to the screen, Huston and screenwriter Ben Maddow have created an atmosphere of authenticity in The Asphalt Jungle that is almost unmatched in films of this period. Moreover, Huston directs The Asphalt Jungle in a very naturalistic manner, which approaches the hardboiled crime tradition from a unique perceptive. Gone are the stylish gangsters toting machine guns that were so prevalent in the early gangster films like Little Caesar. In their place are grubby criminals with weak wills and unfulfilled dreams of success. Furthermore, the meticulous craftsmanship apparent in the robbery plan devised by Doc Riedenschnieder points to a situation which ritualizes crime as an act of salvation. The criminal activity is seen as a means to an end because all the protagonists have “human” needs and desires that have to be fulfilled. For Doc it means chasing young girls in Mexico; for Dix Handley (Sterling Hayden) the hooligan, it means home to the family ranch in Kentucky; for Louis Ciavelli (Anthony Caruso) the safecracker, it means a better life for his wife and daughter; for Gus Minissi (James Whitemore) the hunchback driver, it means a way out of the gutter. However, true to the nature of film noir, these idealistic dreams quickly fade into wasted ambitions and petty obsessions. In addition, these criminals are surrounded by a society, which is as corrupt as they are. This is strikingly demonstrated by the corrupt cop Lieutenant Ditrich (Barry Kelly) in a scene when he attempts to resurrect his tarnished reputation by roughing up the crooked bookie Cobby (Mark Lawrence). Using physical intimidation, Ditrich forces the cowardly Cobby to sign a confession implicating the rest of the gang in the jewellery robbery.

The Asphalt Jungle also provides an overview of a society where the police must cope with crime that is a fact of life in every big city in America (The term ‘asphalt jungle’ can be interpreted as a metaphor for the criminal underbelly of society). This stark and realistic view of society is highlighted towards the end of the film when Police Commissioner Hardy (John McIntire) asserts that there is a need for a committed police force otherwise, “the battle is finished; the jungle wins.” It is also interesting to note that in the original novel by W.R. Burnett, the prime focus is on the police and how they deal with crime in the “asphalt jungle.” But, in the film Huston and Maddow have decided to shift the focus to Doc and his cohorts as they plan, execute, and ultimately fail in their attempt to pull off an ambitious jewellery robbery. In addition, they have chosen to explore the group dynamics between these criminals as a way of slowly building up the tension and anxiety between the men as the heist plan begins to unravel.

With The Asphalt Jungle, gone are the gangland flourishes that were evident in previous crime films, including Huston’s own Key Largo (1948). Crime, as depicted in The Asphalt Jungle is as routine as an eight-hour shift on the packing line. Huston, as if emulating his protagonists, handles the famous heist scene crisply and efficiently, ensuing sensationalism at every turn. With practised nonchalance, Huston depicts the details of the criminal life, guiding the viewer through an understated and revealing insight into the sleazy underbelly of the city. There are no rushed moves, just professional criminals at work. This approach is very effective in drawing the viewer into this twilight criminal world. It is even possible to sympathize with these professional and experienced criminals as they try to pull off a seemingly impossible heist. In The Asphalt Jungle, a man’s character is determined by his professionalism and steadiness under pressure, rather than his adherence to what is morally right and wrong, with the blurring of these moral distinctions being an integral aspect of film noir.

The opening scenes of The Asphalt Jungle set the tone for what is to follow, with atmospheric street scenes depicting a gritty, squalid and seedy part of town (the city is not identified). The viewer sees several brief scenes of Dix (the film opens and closes with him) as he staggers anxiously down back alleyways bleary eyed, until he enters a sleazy diner which looks suspiciously like a front for crime. Dix acknowledges the hunchback behind the counter, his crony Gus. Dix also gives his gun to Gus. Gus then hurriedly hides the gun inside the till as two burly boys in blue arrive. It is immediately evident to the viewer that Dix is in some kind of trouble with the cops and that his crony Gus is willing to help him.

Low-key lighting is also used very effectively throughout The Asphalt Jungle. The viewer is exposed to night-world rooms illuminated by naked bulbs and inhabited by squinting, sweating men. For example, the scenes in Cobby’s bookie joint with its minimal decor, low ceilings and dank, sleazy atmosphere, are perfectly captured by the low-key lighting, which creates a bleak and claustrophobic environment. Low-key lighting is also used very effectively to reveal the psychological state of the characters, emphasizing the subtle nuances of their body movements and facial expressions. This is exemplified in a scene when Emmerich confesses to private detective Bob Brannom (Brad Dexter) that he is broke. The light from the lamp on the table is skilfully used to highlight the stress and tension on Emmerich’s face as he rubs his hands feverishly across a furrowed brow.

In The Asphalt Jungle each camera shot serves primarily as a frame within which the action takes place. The film also has little camera movement, which has the effect of focusing attention on each scene and the actions of the characters within the frame. This attention to detail is further emphasized with visual images that are simple and uncluttered. This is evident in the crucial scene at Emmerich’s house when he, Doc and Cobby are discussing the heist plan. Both Emmerich and Doc are framed mostly in medium close-up at chin level as they discuss the details of the plan. Alternating shots between Emmerich and Doc display the verbal and psychological interplay between these two characters and the suspicion that exists between them, although outwardly, they display a respectful courteously towards each other. There are also several shots where Emmerich is situated in the foreground of the frame and lit in a medium shot from the chest–up. Cobby is standing between the two men in the background, but nearer to Emmerich and in soft-focus. This juxtaposition between the three characters also denotes their hierarchical standing within the criminal world, with Cobby being viewed very much as an underling to both Emmerich and Doc. The minimal importance of Cobby is also highlighted in this scene when Doc speaks, but he is not seen on the screen. The viewer sees Emmerich listening to him, an amused and attentive glow in his eyes, with Cobby standing in the background, watching closely the reactions of both Emmerich and Doc (Cobby is barely in focus). Here, Huston indicates the connivance that ties Cobby to Emmerich, with Doc isolated from the other two characters. Moreover, cinematographer Harold Rosson brilliantly conveys the heightened tension of this scene, his camera scrutinizing and excavating every wrinkle on the faces of these desperate criminals.

Significantly, the above techniques are also strikingly displayed during the tense nail-biting robbery scene. With its atmospheric use of low-key lighting, minimal dialogue and no music, this long and understated scene concentrates on the actions of the criminals, dramatically focusing on their workman-like professionalism. The lack of camera movement throughout this scene again highlights the actions of the characters, with the close-up of Louis the safecracker as he delicately and meticulously places a few drops of “soup” (nitro-glycerine) onto the door of the safe, creating an exciting “edge-of-the-seat” tension for the viewer.

The Asphalt Jungle ends with the failure of the heist and defeat for the criminals. The protagonists involved in the jewellery robbery are either rounded up by the boys in blue, or wind up dead. The authorities are successful in nabbing Doc, Gus and the weak-minded Cobby. The body count begins to rise even before the robbery is over. The safecracker Louis is the first to go, fatally wounded by a gun discharged during the robbery. Dix kills Brannom in a shoot-out at Emmerich’s house, where he is also mortally wounded. Emmerich then commits suicide by shooting himself. That leaves only Dix, who is desperate to return to the family farm in Kentucky. In one of the greatest endings of all time, Dix staggers through the gate of Hickory farm clutching a bloody shotgun wound, his girlfriend Doll Conovan (Jean Hagen) running behind him with tears streaming down her face. Dix then collapses dead in the middle of a paddock surrounded by his beloved horses. It is a dramatic and unforgettable final scene, which may even make the viewer sympathize with the “heroic” effort of Dix to return to his one true love before he dies, Hickory farm and his horses.

The Killing: An Unconventional Noir Heist Film

Like The Asphalt Jungle, The Killing is another great noir heist film. However, as mentioned above, in stark contrast to The Asphalt Jungle, which has a linear narrative structure and is told in straightforward chronological order (beginning with the planning of the heist, then the execution of the heist, and finally the aftermath of the heist), The Killing is an unconventional film in that it employs an innovative and unusual non-linear narrative structure.

Stanley Kubrick’s third feature film (his previous two being Fear and Desire in 1953 and Killer’s Kiss in 1954), The Killing is taut and exciting, the work of a clever and talented young (27 year old) director who is beginning to master the filmmaking craft. Adapted by Kubrick and producer James B. Harris from Lionel White’s novel Clean Break, The Killing depicts a robbery at a racetrack, focusing on the criminals involved in the heist. As mentioned above, both The Killing and The Asphalt Jungle centre on a group of criminals who plan, execute and ultimately fail to carry out a daring robbery. Moreover, Sterling Hayden, so effective as the tough and resolute hooligan Dix Handley in The Asphalt Jungle, returns to the fray again in The Killing, playing a similar “hard-bitten” type of role as the small-time crook Johnny Clay.

The intricate narrative in The Killing centres on ex-convict Johnny, who plans a daring racetrack robbery with the assistance of a motley collection of shady characters, who are portrayed as somewhat atypical criminals. As Johnny remarks to his girlfriend Fay (Coleen Gray) in an early scene, “None of these men are criminals in the usual sense. They’ve all got jobs. They all live seemingly normal decent lives, but they all have a little larceny in them.” Johnny has done a five year prison stretch; Marv Unger (Jay C. Flippen) who is financing the robbery, is a bookkeeper; Mike O’Reilly (Joe Sawyer) the racetrack bartender, is devoted to his bedridden wife; corrupt cop Randy Kennan (Ted De Corsia) has money problems; George Peatty (Elisha Cook Jr.) the betting window teller, is subservient to his wife Sherry (Marie Windsor). Other atypical characters in the film worth noting are Maurice Oboukoff (Kola Kwarian), a chess-playing wrestler who is paid to start a rumble at the racetrack bar and Nikki Arcane (Timothy Carey), the puppy loving sharpshooter whose slurred speech is almost indecipherable. It is also interesting to note that Stanley Kubrick may have been influenced by another “hard-bitten” noir film called Crime Wave directed by Andre De Toth and released in 1955 just a year before The Killing. Not only do Sterling Hayden, Ted De Corsia and Timothy Carry all appear in Crime Wave, the film also resembles The Killing to some extent in its “documentary-like” visual style.

In contrast to The Asphalt Jungle (where the planning of the heist begins to go awry when safecracker Louis Ciavelli is mortally wounded by a stray bullet during the bank robbery), the heist in The Killing does initially go as planned, while the shooting of the favourite horse (Red Lightning) during the running of the seventh race (the $100.000 mile long Lansdowne Stakes) by Nikki serves as a diversion. But, the heist plan starts to unravel when Nikki is shot and killed by the parking attendant while trying to get away. Moreover, Sherry Peatty (Marie Windsor) the manipulative wife of timid George has learned of the plan and tips off her boyfriend Val Cannon (Vince Edwards). Val and a crony then attempt to take the money from the crooks as they assemble to the divide the loot. A shootout ensues and everyone is killed except George (and Johnny who arrives late on the scene). George is mortally wounded, but he is able to stagger home and murder his unfaithful wife before collapsing dead. Meanwhile, Johnny arrives and, after witnessing the aftermath of the shooting, makes off with the money. However, he is apprehended at the airport attempting to escape, when the money-laden suitcase falls off a baggage cart and the bills scatter like confetti in the wind.

Significantly, the above comment made by Johnny about the members of the gang not being criminals in the usual sense can be viewed as a metaphor for the overall narrative structure of The Killing, which is not a typical noir heist film.

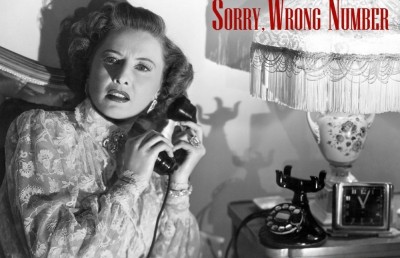

There is no doubt that The Killing does combine a variety of classical narrative elements typical of noir films involving a heist, which would have been familiar to viewing audiences in the 1950s. Along with the central “heist” theme, these elements include the presence of the classic “femme fatale” (Sherry Peatty); the importance of time and the need to meet a deadline; the emphasis on the planning and execution of the heist; and the stark and atmospheric black and white cinematography. In addition, The Killing also uses classical narrative techniques like flashbacks and voice-over narration, which were common in noir films during this period. However, The Killing cleverly uses these classical narrative techniques in an unconventional manner, primarily to develop its non-linear time structure. Most importantly, it is this non-linear time structure and the complex strategy of shifting the point-of-view between the main characters (the technique of following each of the main characters’ actions separately) that re-works these familiar narrative conventions. [4]

As mentioned above, the use of flashback sequences was a standard narrative element in many noir films of this period, including The Killers (Robert Siodmak, 1946), Out Of The Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1947) and The Enforcer (Bretaigne Windust, 1951). But, The Killing uses flashback sequences in a very different way. The ingenious story is assembled in fragments, rather like the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, as the viewer is introduced to the various members of the gang and the part that they will play in the heist. Once one character is established, the film then rewinds and follows another character until all the fragments of the story are complete. This device is used again for the robbery sequence itself, with the film rewinding and following each member of the gang in turn as they carry out their part in the heist plan until the robbery is completed.

Kubrick himself admitted in an interview a few years after the release of The Killing, that an unconventional non-linear time structure was the primary concept behind the film, “Jim Harris (the producer) and I were the only ones at the time who weren’t worried about fragmenting time, overlapping and repeating action that already had been seen, showing things again from another character’s point of view. In fact, this was just the structure in Lionel White’s thriller Clean Break, that had appealed to us and made us want to do the film. It was the handling of time that may have made this more than just a good crime film.” [5]

Voice-over narration is used throughout The Killing and adds to the “documentary-style” nature of the film. Again, the specific characteristics of voice-over narration would have been familiar to viewers in the 1950s from documentary newsreels like the “March of Time” (The characteristics of the voice-over narration in these documentaries include the masculine, authoritative and detached tone). But, in The Killing, voice-over narration is used ingeniously by Kubrick primarily to organize the non-linear time structure of the film. The omnipresent voice-over narration specifies the exact time of the actions taking place. The opening scenes in The Killing begin with the voice-over narration announcing, “At exactly 3:45 p.m. on that Saturday afternoon in the last week of September.” Most importantly, there are different functions that the voice-over narration performs in The Killing. As well as transmitting narrative information and organizing the completed time structure of the film, it also functions as a device that distances the audience from the drama in the film. Paradoxically, however, the use of voice-over narration in The Killing is also very affective in propelling the story forward and increasing the tension leading up to the robbery, which contributes to the feeling of impending disaster that pervades the film. For example, after Nikki shoots the Red Lightning during the running of the seventh race and he is himself gunned down by the parking attendant, the deadpan voice-over narration announces ominously, “Nikki was dead at 4:24 p.m.”

From the beginning of The Killing, the voice-over narration informs the viewer that events begin on a Saturday afternoon in late September and will end a week later when the racetrack robbery takes place. In the first fifteen minutes of the film the voice-over narration introduces each of the main characters. Significantly, the part played by Marv in the heist plan is described by the voice-over narration as being part of a, “single piece in a jigsaw puzzle” that has a, “predetermined final design.” Marv, Mike, and George are introduced at the racetrack; corrupt cop Randy is seen in a bar with a lone shark; gang leader Johnny is at his apartment with girlfriend Fay. These early scenes all take place on the same day, although the time signified by the voice-over narration does vary. For example, the second scene, which is Randy’s meeting with the lone shark, takes place at 2:45 p.m., an hour before the opening scene at the racetrack, which introduces Marv, Mike, and George. Once the main characters have been introduced, the voice-over narration informs the viewer that it is now the following Tuesday morning. The next couple of scenes take place on Tuesday, then the voice-over narration informs the viewer that the time frame has now advanced to the following Saturday, which is the day of the robbery. Subsequent scenes leading up to the running of the seventh race are then organized like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

The viewer learns that the robbery has to be carried out precisely between the start and the finish of the seventh race. As mentioned above, Kubrick ingeniously organizes the unconventional non-linear time structure by continually stopping the film and moving back in time as he follows the actions of each member of the gang separately until the seventh race begins. He also cleverly incorporates “documentary-style” stock footage of San Francisco’s Bay Meadows racetrack to signify the start of the seventh race. [6] For example, stock footage of dray horses pulling the starting gate into position at the track is shown during the opening credits of The Killing. This same shot is then repeated three times as the seventh race begins (overlaid with the voice of the track announcer), as the film shifts back in time to complete another section of the jigsaw puzzle. These racetrack shots at first appear to lack a specific temporal identity, but then become an integral element in the overall design of Johnny’s robbery plan as well as the narrative structure of Kubrick’s film. Furthermore, viewers can also gain a better understanding of the complexities of what is really an ingenious plot that depends on split-second timing and everyone involved carrying out his part of the plan at precisely the designated time. In addition, by going back in time the viewer is able to follow what each member of the gang is doing in different locations at exactly the same time, so that the pieces of the intricate jigsaw puzzle fall into place before the start of the seventh race.

As the heist plan is implemented in the lead up to the crucial seventh race, the narrative begins by following Johnny’s character. At this stage the narrative time structure is chronological. The narrative time structure is also sequential when the film shifts its attention to Mike’s character. It then continues in this linear fashion as viewers follow Randy up to the start of the seventh race. However, there is then a backward shift in time as viewers follow the actions involving Maurice the wrestler. The film then stays with his character until after the start of the seventh race at 4:00 p.m., with the voice-over narration announcing that, “It was exactly 4:23 p.m. when they dragged Maurice out.” There is then another backward move in time as the film switches to Nikki as he arrives at the track. The film then stays with Nikki until he is gunned down in the parking lot. When the film returns to Johnny, it has shifted back in time again. Viewers then follow the robbery through to completion for the first and only time. Therefore, it is only when the robbery has been completed that the final pieces of the intricate jigsaw puzzle are finally revealed to the viewer. In addition, it is also worth mentioning that the viewer is in a more privileged position than any of the characters in the film, being able witness the entire sequence of events as they unfold. For example, there are elements of the story, which Johnny is not aware of. He does not see Nikki shoot Red Lightning. Furthermore, he is not aware of the discussion between George and Sherry about the impending heist. As mentioned above, Johnny is also excluded from the film’s climatic massacre, although he does see the aftermath as George, covered in blood, stumbles blindly out of the building. However, the viewer sees all these actions taking place as well as every aspect of the robbery, although it is only after receiving all the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle that they are able to make sense of the details.

Significantly, there are periods during the film when time is not made clear. Each time the voice-over narration is heard, it informs the viewer of the precise time of the action that takes place. But, when the voice-over narration is not present, the exact time is unclear. In some sequences without voice-over narration, it is only possible to have a general idea of the time of the action. For example, viewers do not know the exact time of the final sequence at the airport, but they know that it is the same evening as the robbery and the massacre. Also, when viewers see the flashback of Johnny throw the bag of money out of the window, the precise time is not signalled by voice-over narration. Viewers only know that it has to be sometime during the running of the seventh race. Moreover, it is also worth noting that the time it takes to run the seventh race and therefore to execute the robbery, has been extended. The protagonists gain valuable time when Nikki shoots Red Lightning in the middle of the seventh race, thus delaying payment to the bettors and giving Johnny an additional few minutes to complete the hold up of the cash office. However, the sense of story events being juxtaposed against measurable time (the distance of the seventh race, which is one mile) is deftly conveyed and cleverly integrated into the overall narrative structure of the film.

The visual style of the black and white cinematography in The Killing (by Lucian Ballard), which includes some moody close-ups of the gang members as they plan the heist, while poring over a map of the racetrack, as well as some on-location scenes would have been familiar to viewers of noir films during the 1950s. But, the film does employ some innovative and unconventional camera techniques, including a variety of clever tracking shots. For example, the tracking shot that follows Marv across the racetrack betting area to Mike’s bar. Other tracking shots worth noting include the scene at the bus depot when Mike deposits the key in the locker, as well as the scene at Johnny’s apartment when he walks through a series of carefully constructed sets. In addition, mention must also be made of the offbeat, almost surreal, massacre scene. Reportedly, the young Kubrick had been at odds with veteran cameraman Lucien Ballard throughout the production. Showing early signs of his obsessive perfectionism, Kubrick apparently decided to shoot the massacre aftermath by himself using innovative hand-held camera angles, which give this scene a raw and aggressive look. [7] This massacre scene is also overlaid by a prominent and unconventional jazz score, which becomes louder as the body count increases.

Significantly, it is also interesting to note that there are two puzzling instances in The Killing, which possibly could be interpreted as examples of Kubrick utilizing a conventional classical narrative technique in an unconventional way. These instances both involve the use of voice-over narration and its accuracy and reliability in specifying the exact time of the events occurring. Moreover, these two instances in the film’s temporal sequencing suggest that the voice-over narration has made an “error” by announcing the incorrect time. Furthermore, it could be argued that these two “errors” indicate that Kubrick not only re-works the classical technique of voice-over narration primarily to organize the non-linear time structure of the film, but possibly also undermines its conventional use as an accurate and reliable source of information. [8]

The first “error” occurs when the voice-over narration announces that, “At 7:00 a.m. that morning Johnny began what might be the last day of his life.” A scene then takes place between Johnny and Marv in which they both discuss their immediate future after the robbery. This scene between Johnny and Marv is then followed by another scene that depicts Johnny arriving at the airport as the voice-over narration announces that, “It was exactly 7:00 a.m. when he got to the airport.” Either there is a genuine error in the film’s temporal sequencing, or the voice-over narration does not account for the earlier scene between Johnny and Marv that occurs before Johnny reaches the airport.

The second “error” occurs when George announces the time as 7:15 p.m. and then declares that Johnny is fifteen minutes late. If George is to be believed (and there is nothing in his character or in the film’s narrative structure to suggest that he would openly lie), viewers must therefore assume that Johnny’s original arrival time was at 7:00 p.m. However, the voice-over narration then announces that Johnny arrived at the meeting place at 7:29 p.m. and that made him, “Still fifteen minutes late.” Therefore, if viewers take this narrative sequence to be of some significance, then either George is mistaken about Johnny’s expected time of arrival, or the voice-over narrator has made an error. [9]

These two unexplained temporal “errors” may indicate that a discrepancy does exist between the action (or what the characters are saying) and the accuracy of the voice-over narration. On the one hand they could simply be explained as an oversight in the film’s narrative structure. However, it seems logical to deduce that in both of the above instances, this explanation appears to be unsatisfactory because announcing the precise time of almost every sequence has been a critical strategy of the narrative structure of the film. Moreover, it is clear that the use of voice-over narration is an integral element in the way in which Kubrick organizes the non-linear time structure of the film. Furthermore, Kubrick is renowned as being an obsessive perfectionist so it is hard to believe that he would have been unaware of these narrative inconsistencies, even at this early stage in his career. [10] Therefore, it has been suggested that if the two “errors” are indeed deliberate, they may constitute an ingenious attempt by Kubrick to undermine the classical convention of voice-over narration as a reliable and accurate means of providing narrative information. [11]

The Killing ends with an ironic and downbeat twist. After the racetrack money lies strewn on the airport tarmac, Fay and Johnny make their way towards the terminal doors. Once outside, Fay unsuccessfully attempts to hail a cab and urges Johnny to run. But, Johnny, a crumpled and defeated man can only mumble, “What’s the difference”, as two burly detectives move towards him with guns drawn.

To conclude, this essay has provided a comparative analysis of two noir heist films, The Asphalt Jungle and The Killing. Moreover, it has examined these two films in relation to classical narrative conventions. As mentioned above, The Asphalt Jungle can be considered a textbook example of a classical Hollywood narrative. It has a linear narrative structure and is told in straightforward chronological order. In contrast, The Killing challenges some of these classical narrative conventions by re-working them in an unconventional way, specifically with its use of a non-linear time structure.

Finally, it is hoped that this analysis of The Asphalt Jungle and The Killing will not only enhance the viewing pleasure of those readers already familiar with these two great noir heist films, but may also encourage readers not familiar with the films to view them for the first time.

Endnotes

1 Peter Hay, MGM: When the Lion Roars, 1st ed., Turner, 1991, p. 274.

2 Stuart M. Kaminsky, American Film Genres: Approaches to a Critical Theory of Popular Film, N.Y. : Dell, 1977, p.102.

3 Eddie Muller, Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir, New York: St. Martins, 1998, p.145.

4 Mario Falsetto, Stanley Kubrick: A Narrative and Stylistic Analysis, Westport Connecticut: Greenwood, 1994, p.15.

5 Selby Spencer, Dark City: The Film Noir. North Carolina: McFarland, 1984, p.120.

6 Thomas Allen Nelson, Kubrick: Inside A Film Artist’s Maze, Bloomington: Indiana U.P, 2000, p.32.

7 Muller, p.154.

8 Falsetto, p.11.

9 Falsetto, p.12.

10 Muller, p.154.

11 Falsetto, p.12.