Fellinian Horror

The Italian director Federico Fellini is best known as one of the central figureheads of the post-world war 2 art cinema. In fact, his art house “hits” La Dolce Vita (1960) and 8 1/2 (flanked by his contribution to the portmanteau film Boccaccio ’70), are arguably the most iconic representatives of art cinema, along with his compatriot Michelangelo Antonioni’s trilogy L’Aventurra, L’eclisse, and La notte, Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries, and Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima, mon amour and Last Year at Marienbad. The lineage from neorealism, to art house, to “Fellinian” has been amply charted by scores of film writers, but my interest in this primarily photographic essay is to chart a lesser noted lineage: a two-street of sorts between Fellini and Italian horror.

Employing a running series of frame stills (taken from DVDs and BDs), my aim here is to reveal a surprising symbiosis between one of Italy’s most revered directors and one of cinema’s most despised (at least by a section of conservative and mainstream critics) genres, horror. The point here is not to suggest that Fellini is a horror auteur, but that his richly veiled visual and aural style, stretching from neorealism to surrealism to expressionism to grotesque caricature, often borrows from horror film imagery and iconography; while in turn has been inflected back to the horror genre in surprising and unexpected places. My aim here is also to try something different as a critical form, and essentially let film images speak for themselves, with a minimum of explanatory text to give a brief context for the comparative frame grabs.

Fellini and Mario BavaI’ll begin by noting the one parallel between Fellini and horror which has often been made by many critics: the influence of Bava’s spectral blonde haired girl as an icon for evil in Kill, Baby Kill on Fellini’s depiction of the devil as a similar blond-haired girl in his segment of Spirits of the Dead, “Toby Dammit, or Never Bet the Devil Your Head.”

Killy, Baby Kill

Toby Dammit

However, this often-cited influence is left for debate when one notices that Fellini used a similar blonde-haired girl in Juliet of the Spirits, in a flashback to Juliet as a child at the circus. Albeit in this case the girl is not a literal ghost, but more of a spiritual phantom for the mature Juliet’s mid-life crisis. The position of the little girl’s hand on the screen is also reminiscent of the iconic hand on window gesture from Bava’s Kill, Baby Kill, making the precise direction of the influence tough to call (although Fellini is on record stating his admiration for Bava’s Kill, Baby Kill). Fellini’s image of a burning angelic girl, or more literally a girl burning in hell, from the end of Spirits also bears the stamp of the horror genre.

When Giulietta (Giulietta Masina) visits her Jungian Shadow neighbor Suzy, whose elaborately ornate mansion stands in stark contrast to Giuletta’s pedestrian bourgeois home, she encounters a bevy of sexualized female guests who tower over and literally devour their men. Two images in particular may as well be out-takes from a future Hammer vampire film!

Juliet of the Spirits was Fellini’s first feature length film shot in color (Technicolor) and is marked by a saturated, candy-coated and at times kaleidoscopic color palette that was a possible influence on other Italian horror auteurs known for their striking use of color, Mario Bava and Dario Argento.

Juliet of the Spirits

Suspiria

Lisa and the Devil

The use of saturated reds and blues which is such a cited aspect of Suspiria (and Inferno) can also be traced to Fellini’s Roma, 1972:

Fellini’s Roma

Suspiria

The influence is also evident in the set design and art design in Fellini and Argento. The striking use of monumental, marble foyers and art deco styled furniture carries across from Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits and Fellini’s Roma to Suspiria:

Fellini’s Roma

Suspiria

Within these overwhelming spaces often reside powerful matriarchs, sometimes butch looking, which we can see in Fellini’s Roma and Suspiria

Fellini’s Roma

Suspiria

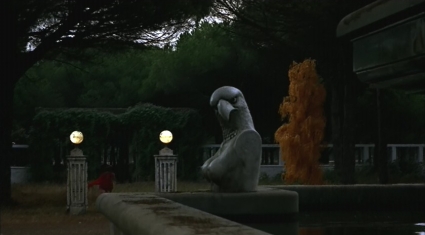

The striking peacock which adds a colorful yet disquieting affect to the climax of Suspiria can be traced back to Fellini’s Roma.

While the burning angel cited above from Juliet of the Spirits is suggested in the close-up of a murder victim in Suspiria

Fellini’s influence on Suspiria goes back even to his black and white 8 ½, where lighting and set design shows the influence rather than color. The scene in question is when Guido is honored by a visit with the monsignor in the steam baths, only to be met not by the monsignor in the direct flesh, but as a silhouetted spectral figure seen through a veiled curtain.

8 ½

The eerie effect is lifted and tweaked by Argento for the famous makeshift dormitory sleep-over scene in Suspiria. In the scene the owners of the ballerina school set up a large camp-like tent in the middle of the gymnasium as a makeshift dormitory for the girls to sleep in while their rooms are being fumigated. During the night a few of the girls are visited by a demonic presence seen only in silhouette through the red and green lit curtains.

Suspiria

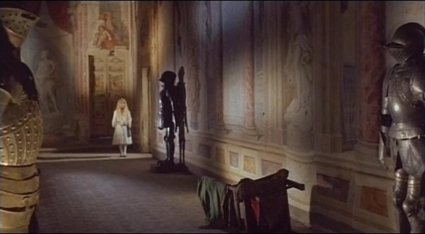

With its dark fairy-tale quality Juliet of the Spirits seems to also have been an influence on Bava’s Alice in Wonderland flavored Lisa and the Devil, especially the baroque mansion where much of the disorienting events occur for the lost Lisa character. For both women, Juliet and Lisa, the trip into the mansion is literal for the viewer but figurative for the characters, who are stepping into a twilight zone of shifting time frames, ‘living dead’ or ‘living mannequins’ (Lisa) and Jungian psychic formulations (Giulietta).

Juliet of the Spirits

Lisa and the Devil

One of Bava’s pet horrific tropes is bringing the inanimate to life, or animating inanimate objects such as dolls, mannequins, and corpses. Such imagery works at an unconscious level of primal fear, invoking Freud’s famous theory of the “uncanny” or the ‘un-heimlich” (the strange made familiar). In Freud’s essay “The Uncanny” he argues that in our psychic development we block unpleasant memories, primitive beliefs, desires, but when we see something that reminds us of this repressed memory, we get the noted strange uncanny feeling, the strange made familiar; as the repressed emotion attempts to crawl back into our consciousness, we become attracted (pulled to it) but afraid (push away) because it is “uncomfortably strange”. Freud mentions two formulations of the uncanny:

1) reviving a repressed emotional impulse (scary or not, a return of the repressed)

2) something that suggests that magic, animism, or the irrational is true (a doll)

The use of inanimate objects was key for Freud in evoking the uncanny because they relate back to our infanthood, when we were not able to always distinguish between the animate and inanimate. Seeing life in stillness, animism, is a key in many Bava films, with ghostly wind knocking over furniture in Kill, Baby Kill, the corpse coming back to life like a mummified mannequin in the story “A Drop of Water” from Black Sabbath, and a host of inanimate objects seemingly coming to life across many films, from mannequins, to armours, to chairs, to dolls, to balls.

“A Drop of Water”

One of the most terrifying images of the uncanny I can recall comes, however, from Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits, in the shape Giulietta’s mother, played by the statuesque Caterina Boratto. The domineering mother appears in her ‘normal’ human form in several scenes (although always larger than life compared to the diminutive Giulietta), but during the fiery climax, where Giulietta encounters the real and psychic figures of her life as “spirits of the dead” the mother appears to her as a monstrous corpse-like mannequin.

It’s certain that Bava’s use of the uncanny most likely did not come directly from Fellini, but Fellini’s image would not look out of place in a Bava film.

Bava used the “horrifying” corpse as mannequin effect conventionally in the noted “A Drop of Water” climax, but would also use it in more subtle and sophisticated ways, such as the opening credit scene of Blood and Black Lace, where he places haut couture fashion models (lead characters soon to be victims) opposite their mannequin doubles:

And again in Lisa and the Devil where the devil/trickster character Leandro played by Teddy Savalas transforms characters from mannequin to human form, and where the mansion itself is populated by a motley group of ‘living dead’ aristocrats.

In a subtle gesture, a mannequin held under Leandro’s arm changes to human form in the same scene (across an edit), without any attention being called to it (I’d say this is a joke Bava plays on the audience, since it clearly goes unnoticed by the character interacting with Leandro, Lisa).

Mannequin to human

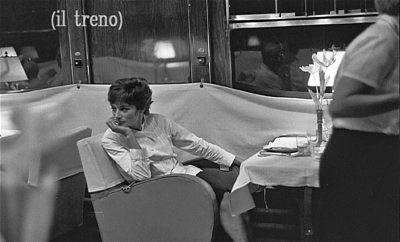

One of the most satisfying and surprising finds I have encountered in my research on Fellini and Italian horror was facilitated by the fascinating documentary on the recent Criterion Blu-Ray release of 8 ½, The Last Sequence, a new 52 minute documentary that digs into the lost alternate ending of the film. Although there is no remaining footage of the ending, the BD includes set photographs and interviews with key actors and crew who were on the set, remembering details of the alternate ending. From these accounts the alternate ending consisted of Guido embarking a train, which he slowly learns is populated by phantom spirits of key figures of his life. The actress Claudia Cardinale remembers that they were all supposed to be dead, that there was no dialogue, and that it felt like a sort of dream. Actress Anouk Aimée, recalls: “We were dead or something. There was a sense of death there.” (18’55”, BD). Tullio Pinelli, screenwriter, adds, “I remember this train, travelling along, full of spirits or phantoms dressed in white. It left me with a tragic feeling, like a funeral.”

Tulio Pinelli

Anouk Aimée

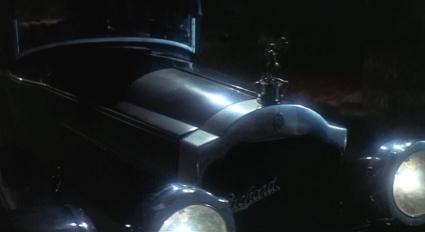

What’s most striking about this is the certainty (barring a coincidence of huge proportion) that Bava (or one of the many screenwriters, or Alfredo Leone) had known about this alternate ending and revised it for the ending of Lisa and the Devil, replacing the train with an airplane. In the conclusion of Lisa and the Devil Lisa escapes unharmed from her Alice in Wonderland-like experience at the mansion of a family of decaying aristocrats, led by a blind Contessa (Alida Valli) and her neurotic son, Maximilian (Alessio Orano), who thinks Lisa is the reincarnation of a former lover now presumed dead, Elena. She leaves the mansion, which now appears decrepit and unlived for years, and takes a bus to the airport. She boards the plane and walks through a series of empty sections before coming across a section peopled by the ghostly figures of Maximilian and others from the mansion.

She runs off toward the cockpit, only to find the ‘devil’ figure, Leandro, at the helm of the plane. She slumps to the floor frozen like a mannequin, but now dressed and made-up as Elena (who we saw earlier in flashbacks). Has Lisa become Elena? Or was she Elena all along? Although the stories are different, the dynamic of the lead character entering a ‘safe’ space (train or airplane), only to be met by spirits of her past is unmistakably (I would guess) lifted from Fellini’s alternate ending to 8 ½.

The connections persist beyond the grand auteurs I’ve noted thus far, Mario Bava and Dario Argento, to lesser lights such as Alberto De Martino and his interesting post-Exorcist The Antichrist, 1974 (one of the best films to have followed the success of The Exorcist). An early scene of devout Catholics on a pilgrimage shows at times a shot for shot influence of a similar pilgrimage scene in Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria

Nights of Cabiria

The Antichrist

The soul in battle in The Antichrist is a mentally troubled, paralyzed woman named Ippolita (Carla Gravina), who becomes possessed by an ancestral heretic nun and begins to act like a nymphomaniac on acid. The make-up, hair-style, body gyrations and delirious expressions of Ippolita in her possessed state are uncannily similar to a composite of the mannerisms of the psychic seer that Giulietta visits, Pijma (Valeska Gert), and one of the women at Suzy’s hedonist palace.

Juliet of the Spirits

The Antichrist

I would like to conclude with a few more isolated examples of this surprising parallel between Fellini and the horror genre. The appearance (in the literal and figurative sense) of certain Fellini performers shows a continuity with the horror genre, starting with the British actress who went on to have a formidable career in Italy as an iconic Scream Queen, Barbara Steele. Steele’s breakthrough horror role came in the dual role she performed in Bava’s Mask of Satan / Black Sunday, 1959, as Katia and Asa Vajda. Fellini, a lover of remarkable faces, hired Steele to play Mario Mezzabotta’s (Mario Pisu) trophy girlfriend Gloria Morin in 8 ½.

Bava, top, Fellini bottom

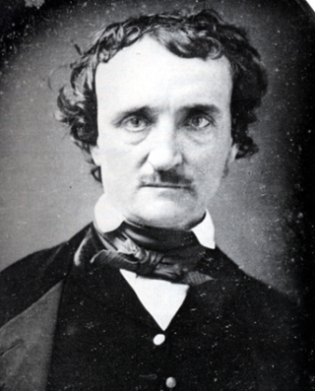

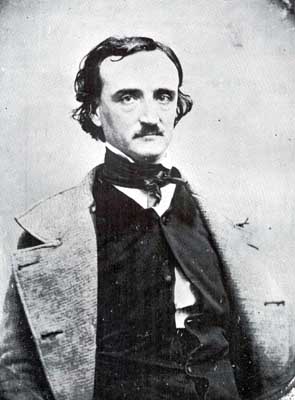

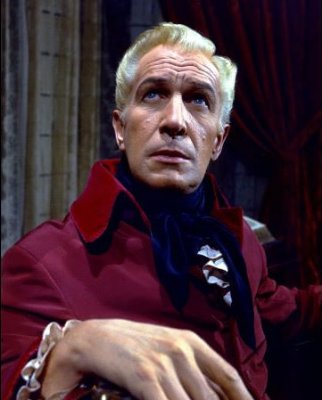

For the Poe-based story “Toby Dammit” in Spirits of the Dead (1968) Fellini used the young, handsome Terence Stamp, who was coming off a run of six or seven strong English films, to play a British super-star in Rome to promote work on his latest film, a “Catholic Western.” To transmit the look of a harried, disinterested actor, Fellini had Stamp dye his hair a bleach blond which not only echoed the blond hair from the women in Juliet selected above, but more tellingly, Vincent Price in his role of Roderick Usher in Corman’s House of Usher, 1960. Stamp’s hair and make-up also suggest that Fellini was thinking more directly of Poe himself.

Top to bottom, Poe, Price, Stamp

The Temptation of Dr. Antonio, from the 1962 portmanteau film Boccaccio 70, was Fellini’s first foray in color. For his contribution Fellini cast the great comic actor Peppino De Filippo as the arch conservative Dr. Antonio Mazzuolo, who begins a one man crusade against a park billboard advertising milk through the well-endowed physiognomy of actress Anita Ekberg. His own repressed sexuality results in a delirious hallucination where he is chased, King Kong style, by a 50 foot Ekberg.

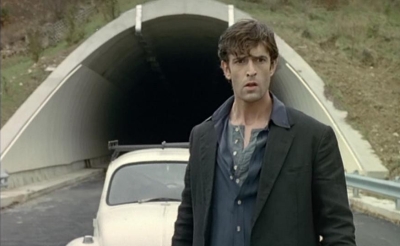

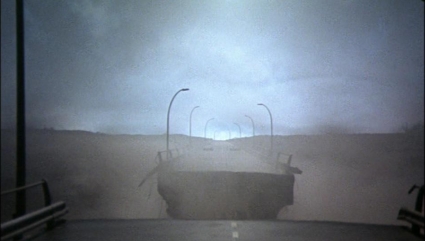

I’ll end fittingly with perhaps the last great Italian horror film, because it is itself a conscious summation of Italian horror history, Michele Soavi’s magnificent Dellamorte Dellamore. In the final scene, the caretaker of the Buffalora cemetery, Dellamorte Dellamore (Rupert Everett) and his dimwit sidekick Gnaghi (François Hadji-Lazaro), finally seem to escape their insular world of the Buffalora cemetery by taking to the highway in their car. When they realize the road ahead of them ends in a Daliesque meld of curled steel and asphalt, giving way to a precipice, Dellamorte comes to the realization that there is no world beyond his own, which he is forever trapped in, like the snow globe at the film’s start and end. This metaphysical conclusion, with a road transforming into an abyss, comes directly from the end of Fellini’s only true foray in the cinema fantastique, “Toby Dammit.”

Dellamorte Dellamore

Toby Dammit