Fantasia 2009 Report 2

Urban Squalor Meets the ‘Im/Purity’ of Whiteness

Fantasia always come serving a full plate of succulent morsels for the new and faithful fans of this ever growing (in size and importance) international genre festival. In this year’s servings I noted an unusual somewhat dialectical aesthetic pattern of films dealing with urban squalor, and films relying on an aesthetic of ‘purity’ through a mise-en-scène of all-white walls, white clothing, saturated lighting and overexposed, blinding light. An ‘auteur’ of the former was one of the many invited guests of 2009, the New York based filmmaker Buddy Giovinazzo, who is interviewed in this issue. Giovinazzo is best known to horror fans for his low budget cult favorite Combat Shock (aka American Nightmare), a searing, gritty urban study of an ex-Vietnam’s psychic meltdown. Accurately described by Giovinazzo as a “cross between Erasherhead [the domestic setting, the surreal baby, the sense of urban alienation/isolation] and Taxi Driver [the New York/Staten Island setting, the depiction of urban low-life, through poverty, drugs, prostitution, violence]” Combat Shock is a 1986 film that attempts to capture the social horror ambience of American films of the 1970s, lauded, referenced, and invoked by contemporary directors such as Quentin Tarantino, Eli Roth and Alexandre Aja. As a rare treat, director Giovinazzo brought his personal uncut 16mm print of Combat Shock to screen at Fantasia. Also playing at Fantasia was his most recent American film, Life is Hot in Cracktown (2009), based on his own same titled 1993 collection of short stories.

Combat Shock Squalor

Urban SqualorLife is Hot in Cracktown revisits the urban squalor of Combat Shock and concentrates on the interconnected lives of four sets of characters touched in varying ways by the cycle of drugs, poverty and violence (an example of what scholar David Bordwell has christened ‘network narratives’). Cracktown eschews the bouts of surreal and graphic violence of Combat Shock in favor of a more realistic style, with a stronger script and an impressive ensemble cast. The interconnecting sets of characters include 1) Manny (Victor Rasuk), a hard working Latino who works two jobs, a late shift in a dangerous all night convenience store and a security guard in a rundown, drug-infested Welfare hotel, where he lives with his wife, Concetta (Shannyn Sassomon), and their sick infant; 2) Willy (Ridge Canipe), a ten year old boy, who lives in the Welfare hotel with his younger sister and their drug-addicted mother (Illeana Douglas) and her violent boyfriend (Edoardo Ballerini); 3) an oddball couple that brings touches of humor to the occasion, Marybeth (Kerry Washington), a pre-op transsexual working as a prostitute and her live-in lover/pimp, and somewhat dim-witted Benny (Desmond Harrington), and their ‘rich’ post-op transexual friend Ridge/Gabrielle; 4) and a young, angry African-American street gang member Romeo (Evan Ross), living with his older sister and ill mother. One of the strengths of Cracktown is the writing, which makes heroes out of villains. Giovinazzo does not demonize his characters, or paint them as simplistic victims of their social environment. Their weaknesses humanize them and in the end we are touched by the ability of tarnished characters to rise above the squalor around them and produce genuine acts of compassion, sacrifice and love.

Manny facing the reality of urban crime

Life is Hot in Cracktown is an example of what David Bordwell has christened network narratives, films which have several sets of main characters and interconnected stories, rather than two or three characters and one main plot (“…those films highlighting several protagonists inhabiting distinct, but intermingling, story lines”). (Requiem for a Dream, Crash, Traffic, Magnolia, Short Cuts, 21 Grams). In a network narrative the different sets of characters usually live in the same city or contiguous space (one tenement building for example or the same neighborhood) but do not necessarily interact with each other (though they sometimes pass each other fleetingly). Rather than interacting directly they are indirectly related by theme or circumstance. Either by chance or design, many of the contemporary incarnations of network narratives deal with the subject of drugs (City of Hope, Requiem for a Dream, Traffic, 21 Grams, Life is Hot in Cracktown). Taking a page from the great network narrative Requiem for a Dream, the film climaxes with a rapid montage of the four sets of characters dealing with their own particular crisis. Will Benny leave the hospital alive or die in Marybeth’s arms? Will Romeo survive the vengeful assault of a rival drug lord? Will Manny die needlessly at the hands of a gun-wielding strung out junkie trying to rob the convenience store where he is employed? Will Willy leave his defenseless sister behind in an attempt to escape the cycle of poverty? In a sense there is more at stake in these mini-narratives than the death of a central character, but the failure of humanity.

Marybeth

There were two films with completely different tone and style that received their world premieres at the 2009 Fantasia International Film Festival (July 9-27, 2009): Must Love Death (2009, Andreas Schaap, Germany) and Neighbor (2009, Robert A. Masciantonio). Both feature one of the most recurring, identifiable and indeed iconic images in contemporary horror: a victim strapped to a chair (and tortured); both films also have moments of black humor, but in Neighbor the humor comes with much more of a cutting edge, while the doubling narrative structure of Must Love Death, from burgeoning romance to psychopathic character study, keeps it from becoming wholly morose.

Must Love Death is a film that gleefully embraces an identity crisis of grand proportions, fusing two of the most incompatible genres imaginable, the venerable romantic comedy and the currently popular torture porn. While the mix seems improbable, it actually works because of a playful, contagious energy that forces through some awkward opening moments to forge an original, quirky blend of reflexive banter and sincere (if seriously offbeat) characterisation. The film’s identity crisis goes beyond genre to production history, as the film is ostensibly a German film disguised as an American film, with mainly German actors who underwent voice training to soften their German accents. And it works for the most part, with the odd German inflection slipping in every now and then. The film forces its ‘Americanness’ on the viewer with wall to wall American and Anglo-Saxon popular culture references (Star Trek, reality TV, rap music, country music, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Night of the Living Dead??¸??The Shining, The Evil Dead), and an infectious (and surprisingly good) original music score in the tradition of American pop/country/rap idioms. The latter is organically weaved into the story, as the main actor, Norman (Sami Louis, a young Art Garfunkel look-a-like), is a musician, which leads to many recording studio scenes and the integration of his compositions as source music.

The film begins with the eponymous, “inspired by true events,” recalling one of its obvious influences, Texas Chainsaw Massacre. It opens with a sex scene in a car between nymph Heather (Katjana Gerz) and Thorsten (“from somewhere in Europe”) (Tobias Schenke), two characters come back into the narrative later as victim fodder. The story is simple. Norman, depressed because his girlfriend has left him, decides to commit suicide. Lacking the stomach to do it alone he discovers like-minded people on the internet and joins them for a planned collective suicide. When he arrives at the designated cabin in the woods he meets three other apparently suicide bound people, an attractive young woman Liza (Lucie Pohl), and rural bumpkins Sean (Jeff Burrell) and Gary (Peter Farkas), the owner of the cabin. Before long Norman discovers that the suicide club is a ruse and that Sean and Gary are a couple of harebrained psychotics who lure people to their cabin to ‘star’ in their fantasized reality television show, “To Torture…or no Torture”. Before the torturing begins the film flashbacks to the moments leading up to the cabin trip, which establishes the romantic entanglement between the twenty-something Norman (Sami Loris) and attractive waitress Jennifer (Manon Kahle), who is in a pointless relationship with an egotistical, obnoxious, Lothario television actor named Foxx C. Bigelow (Philipp Rafferty). Structurally the film intercuts between two worlds, the colorful, light, romantic Woody Allenesque New York city, and its harsh, on the outskirts of New Jersey torture cabin setting. While Norman is the one character who moves fluidly between the two worlds –in the cabin in the present, in New York in the recent past– Jennifer resides primarily in New York, until the ending where she is encouraged by her waitress friend and grizzled diner regular to follow her heart and go after Norman, which takes her to the cabin.

The contrasting nature of the two environments leads to one of the film’s best scenes, a deftly crosscut sequence between Jennifer in the Metro Diner listening to Norman’s ballad on the diner radio, and a violent torture scene in the New Jersey cabin where the psychos force Heather to fire a nail gun at a blindfolded, tied down Thorsten. The crosscutting begins with Sean introducing his ‘reality TV’ camera to the next torture weapon, “the nail gun,” which is followed by a cut to a New York city street, with a red rose garden in the extreme foreground of the shot establishing the red motif that will bind the two locations (Jennifer wears a red hat in the diner, the diner seats are red, red is the color of love and blood). As Jennifer listens to the song, we can sense her love for Norman growing and being nurtured by her two companions, a fellow waitress and an older man. Norman’s romantic ballad plays over both locations, serving an ironic counterpoint to the powerful yet divergent emotions being expressed across the two locations, smoothing over harsh straight edits from characters in great physical pain, to characters smiling and laughing. The crosscutting ends with a brilliant edit from blood dripping off Thorsten’s finger, to a close-up of red sauce being poured over a plate of food (though brilliant the edit is not entirely original, since an identical cut occurs in the New Zealand film Jack by Nimble, 1993).

In the flashback scenes, Jennifer and Norman meet in a figurative big bang, with a distracted Jennifer accidentally hitting Norman as he crosses the street, the impact sending Norman skyward, with repeated slow motion shots of the airborne Norman spinning majestically like a gymnast. The impact was so hard that Norman should have logically died, but he somehow comes out of the accident with, literally, a scratch on his finger (which we see him being treated for in a hospital). This sets up one of the film’s many running gags, as Norman escapes one near death experience after another (hangings, shootings, endless torture, etc.). The usually symbolic overhead angle used to frame Norman’s inert body after the car crash and again at the end after being mistakenly shot point blank by a sheriff (which echoes Ben being needlessly shot at the end of Night of the Living Dead), perhaps suggests that Norman has already died and is simply reliving the death experience over and over.

While some horror fans may feel restless during the romantic New York scenes (or sheepish that they are enjoying them), they will feel in familiar territory during the very dark, very black comic New Jersey/cabin scenes, where Norman spends most of the time tied to a chair being tortured or watching others (Liza, Heather, Thorsten) being tortured by two of the silliest, most domestic (closeted gay?) psychos you will ever come across. The two killers interact like a married couple, with the slightly retarded Gary feminized through his obsession with cleanliness, his apron and yellow latex gloves, and effeminate mannerisms. The sheer amount of physical pain and discomfort that poor Norman endures during the course of the film –left to hang by his neck, getting hit by a car, having his fingers snapped, nails pounded into his forearm, a spike through his feet, getting shot at– brings back memories of cinema’s greatest masochist, Ash Williams!

If the plot of Must Love Death is simple, it is complex in comparison to the plot of Neighbor: a twenty-something, svelte, athletic dark-haired woman referred to as ‘the Girl’ (played with great gusto and energy by America Olivo) terrorizes a middle class suburban neighborhood by entering homes and torturing and killing its inhabitants. That is it as far as plot goes. And the viewer, along with the victims, is left in a perpetual fog as to why this young woman is enacting these heinous crimes. There does not seem to be any reason for why she chooses one home over another, or character revelation (who is she? where does she come from?).

Interspersed throughout her murders we hear television newscasts announcing that someone has escaped from an institute ‘three days’ ago. We logically assume the news item is referring to the ‘girl,’ to give us some hope of an explanation or rationalisation for her actions; but this is only a ruse when we later learn that the person has been caught. When one of the somewhat developed characters, Christian (Don Campbell), becomes victimized by the ‘girl’ he expresses what any rational person in such a situation would want to know. Why me? Unfortunately, the world we live in is often not a rational place, and films like this follow suit. The first time he asks her she responds by asking him how it is that he can live in such a nice home, suggesting some anarchistic, political (attacking the rich) reason for her criminal actions. This is lightly underscored by another scene where she angrily destroys a random selection of material goods in one of the homes she has invaded. The second time she is asked by the victim, the girl seems poised to render an explanation, almost seems to be empathising with his need to know, and then teases us/him by uttering, in a quivering voice, “Why. Because…because….well, it doesn’t matter anymore.” Hence by the end of the film, after we have seen her torture and kill whole families and narrowly escape capture (deceptively played out in some wonderfully effective ‘mind fuck’ twists), we know as little about her at the end of the film as we did at the beginning. What we do learn from the film is that this ‘girl’ reacts to and treats her violent behaviour with the same range of emotions a ‘normal’ person would experience across a lifetime: boredom, rage, indifference, anger, excitement, passion.

Another recent female psycho, Béatrice Dalle the ‘woman’ in À l’intérieur, also abruptly breaks into a home to terrorize a woman, but by the end we get a reason for her actions. What makes the behavior in Neighbor especially disarming is that we are never even shown how the woman ‘breaks’ into these homes. Or the details of how some of her victims get from point A (innocent) to point B (victim tied in a chair). She also does not seem to care much about covering up her crimes and leaves each home as if nothing has been touched. In the finale scene when we see her walking away freely dressed in black from head to foot, with nary a moral stance offered by the text, the idea flashes our head: is she a modern incarnation of the devil? Death itself? Or evil personified?

The opening scene sets the stage for the intense nature of her self-delusion. It opens with our introduction of the ‘girl’ character, comfortable in a housecoat, seemingly at ease in familiar surroundings of her kitchen. She pours herself a bowl of cereal, takes a few spoonfuls, and switches the counter television set off. She places the bowl down, moves into the living room, turns on the stereo and begins to dance to the music. The camera follows her closely but from a safe distance. She prances back to the kitchen, takes the cereal bowl and dances her way up the stairs to the second floor. A steadicam follows her every move up the stairs and around the landing. When she opens a bedroom door the scene cuts to a close-up of her face, emoting with genuine fear, shock and sorrow, whatever she is seeing off-screen. The scene now cuts for the first time to a subjective point of view, with hand-held close-ups (perhaps to suggest her unstable mind) of bloodied and cut up bodies. We cut to a farther vantage and see a man and a woman tied and gagged to opposing chairs. She bends over toward them, holding back a vomit, and crying in front of what we assume to be her dead parents, before breaking into a laughter that reveals her show of tearful horror has only been play acting. The question is, who is she play acting for? Clearly not for them, since they already know she is nuts. You can say she is doing it to amuse herself, but from a purely narrative standpoint, the act is intended to fool the audience, which sets up a subtle theme of manipulation and reflexivity which the film develops in several ways (the playful narrative twists between reality and fantasy, the pointed references to other hostage/torture films). For example, the man is still alive, barely. She takes a faucet spout and rams it into his chest, then turns the faucet ‘on’ and fills up her glass with his chest blood gushing out of the faucet. In what can only be described as a reflexive gesture, she turns to an unfinished canvas on an easel behind him, dips a paint brush into the wine glass and uses his blood as paint. The gesture assures us that the film we are about to see is all an artistic construction, “murder as art.”

One of the ways in which director Masciantonio undercuts the intensity is by interjecting does of intertextuality, such as the recurring references the Girl makes to previous hostage/torture films, such as quoting Laurence Olivier in The Marathon Man (“Is it safe?”), Misery, and A Clockwork Orange, and references to many other horror films (An American Werewolf in London, The Man Who Laughs). And as dark and disturbing as the film is, there are also moments of near slapstick humor. For example, after a particularly nasty torture scene, in which she drills holes into a victim’s thighs and then places a large worm into one of the open wounds, the Girl goes to the kitchen to make herself a sandwich. That she has an appetite after her violent action is funny enough, but when she nicks her finger with a kitchen knife and begins screaming in horror over a tiny cut in her finger it places her violent behaviour in a bizarre, almost child-like psychological context. After one of her violent incursions –slitting open a woman’s forearms– produces a river of blood that shocks even her, she replies with comic candor, “Now that got a little crazy!”

What sets Neighbor apart from the slew of recent horror films featuring torture is that the perpetrator is female. It may seem that director Masciantonio has made his villain a woman for no other reason than the novelty and shock of having a female killer, but it also serves the story. As a woman, potential victims let their guard down or put themselves in a more vulnerable position because they don’t harbor (consciously or unconsciously) any fears toward a woman and hence do not see her as a potential risk or threat. Director Masciantonio plays his audience like a violin, performing a perfect slip from the killer’s relentless sadism, to the psychological effects of her kidnapping and torture on the traumatised victim, and then back to the killer’s gut wrenching violence. Masciantonio even gives us a scene of the Girl taking a shower to wash off the blood, which plays on the typical scene of the victim who takes a shower to cleanse or purify herself (usually from a rape, attack, or a murder). But there is no such purification here.

Every year Fantasia has a film which seems to up the ante for visceral violence and contains one moment of violence which becomes hard to shake. Over ten years ago it was the wire brush to the lips scene in Doug Buck’s short Cutting Moments. Self-mutilation and paraphilia sent audiences scampering for their barf bags in 2006 with the Neighborhood Watch. Last year the bar was raised by the self-mutilation in two shorts Snip (a man stands in front of a mirror and takes a straight razor to his whole body) and Electric Fence (a man possessed by the mind of a pedophile uses a pair of dull scissors to castrate himself). In the 2009 edition that special moment occurs in Neighbor, and again in a film filled with squeamish violence (attacks on fingers, thighs, toes, kneecap, cheek), it is a surreal assault on the male sex organ that will have audiences shaking their collective heads (although what she does to a mouth with a hacksaw is a close second). Think Miike’s Audition meets Oshima’s Realm of the Senses. Neighbor revels in its character’s sadistic nihilism, without ever taking a moral stance (is that even necessary?) or explaining who the killer is or why she is committing these horrible acts of torture and murder. The official website has a series of videos including clips and interviews promoting the film.

Urban squalor was in evidence in many of the films featured in the Japanese Pink Cinema and Roman Porno retrospective that was one of the highlights of Fantasia 2009. Each film was treated to an excellent introduction and question and answer period by Jasper Sharp, author of Behind the Pink Curtain: The Complete History of Japanese Sex Cinema, published by FAB in 2008. Confidential Report: Sex Market (1974, Noboru Tanaka) opens with a wide angle long take on 19 year old prostitute Tomie (Meika Seri.) telling the camera, “I will do anything I please.” And what seems to ‘please’ her is competing with her prostitute mother for the few clients that come their way. In fact the mother/daughter economic competition recalls Onibaba, where the mother and daughter compete for the armour of dead samurai that fall into their ditch trap. The film begins in a hard edged realist style, with its black and white image, hand held camera, and sweaty close-ups, but slowly becomes much more impressionist and ambient. Tomie lives with her mother and mentally challenged brother, an unwanted product (we assume at the end, when the mother is once again pregnant) of ‘work.’ Tomie feels sorry for her brother so masturbates him (with some kind of rubbery animal product, perhaps whale blubber) and even has sex with him. Like most pink films, the sex on offer does not provide easy titillation. It is sullied and de-eroticized through the lack of human warmth between the people having sex, or sense of pleasure, especially on the part of the women. Most of the ‘johns’ are men from the Osaka neighborhood. Tomie flaunts her youth in front of her mother, like the scene where she is sent (by a pimp) to rescue a client from an ‘old woman’: her mother. There are some really wonderful shots in this film, which is especially striking considering the film was shot very quickly. The most outstanding is the single long take shot of Tomie having sex with her brother, toward the end, where the lighting subtly changes during the shot, as if time itself were advancing, or the outside light source was changing dramatically. The long take begins with the characters bathed in blackness but (after the camera dollies in) it ends with her face lit by a bright sunlight coming in from the window. The film is really a series of vignettes of Tomie with her varied clients, the pimps, the locals (a man who recycles condoms by washing them, placing them out to dry, putting talc powder in them), her mother, her brother, an attractive man who appears twice as her knight in shining armour, her savior, but who she rejects at the end, preferring to stay with her kind.

There is one odd diversion of a sequence, which follows a young, timid, long-haired man who propositions a friend of Tomie’s, but is too shy to convince her pimp that he is up to the sexual task. Instead the pimp buys the man a sex doll, and the timid man follows the prostitute and the pimp around town dragging along the doll. They end up inside a silo, which explodes and kills all three of them.

After the sex scene with her brother –a seemingly positive moment– Tomie discovers that her mother is pregnant. She comes to realize that she and her brother were born in similar circumstances, a vicious circle of poverty and prostitution. The film switches to color (a temporary escape from reality?). Her brother places a rooster on a leash and goes on a meandering walk that has him end up on the top of a tower. He throws the rooster off the tower, but it hangs caught on the railing. He walks back down the stairs to the road and hangs himself. Tomie finds the body, refuses the man who is her potential saviour, who has appeared out of nowhere, a suggestion that perhaps he is a manifestation of Tomie’s imagination, and returns to her miserable life. In a morose ending, she now sees herself as nothing more than a sex doll, and wants her client to treat her like one by placing a cigarette in her vagina. The film has many other near sublime visual touches: the early sex scene with the camera framing Tomie and her lover taking her from behind both pressed up against a window; the scene where Tomie, again taken from behind, with her face toward the camera, literally replicates a swinging camera by moving her face toward/away from the camera. The extreme anguished and angered expression on her face recalls the final CU at the end of Mizoguchi’s Sisters of Gion. Confidential Report: Sex Market was one of the better Roman Porno films in the retrospective.

Urban squalor comes home to Canada (for Fantasia any way) with the Toronto-set Sweet Karma (2008, Andrew Hunt), which marks a rare Canadian exploitation, female rape revenge film which plays by the rules on one hand, but adds a Canadian style sucker punch by having the whole motive for the revenge evaporate in thin air, deflating the sense of catharsis that normally comes with the territory. The only other Canadian film with a similar dynamic is Fruet’s Death Weekend, where Brenda Vaccaro plays a woman raped by an invader who turns on her aggressors. An attractive, mute Russian woman named Karma (Shera Bechard) travels to Toronto to track down the operators of a Russian-run sex trade organization which her sister fell prey to. The film does a great job in setting up the sex trade milieu, with some of the best strip bar scenes I’ve ever seen. The largely Russian people running the show are well cast, especially the man in charge of running the nut and bolts of the operation. Shera Bechard plays the avenging mute sister Karma Balint, seeking her sister through the grimy Toronto underground. Balint is a clever, resourceful character, but not one without faults and is prone to miscalculation driven by her emotions. The film cuts back to Russia, and shows Balint’s close relationship with her sister. We learn that Karma was present the moment where she agreed terms with the Russian contact, a middle-aged woman, who tells the women that they are going abroad to work as domestics. Once there they are forcibly taken (essentially kidnapped) and ‘trained’ to be prostitutes. If they don’t comply, they are beat, raped, or have their family back home threatened. One of the new recruits is too weak to stomach the initiation and commits suicide. In one of the flashbacks we see Balint killing the middle woman in Russia. This one shows the influence of other revenge films too, especially The Limey, where we also have a character searching for the killers of her daughter (rather than sister), and arriving to a foreign city (England to Los Angeles, rather than Russia to Canada). Scenes of Balint contemplating her next move in her hotel room, the use of newspaper clippings, and the non-linearity (though not to the same extent) all demonstrate the influence of The Limey. Director Hunt also inverts elements of The Limey; for example, whereas the Stamp character in The Limey is loquacious, Balint is mute. And, like in The Limey, in the end the central character does not complete the revenge plan to its end. When Balint discovers that her sister is actually alive and living with a wealthy man who ‘paid’ for her release, she has a change of heart and does not kill the man (won over by her sister’s pleas of mercy that she loves the man). Likewise at the end of The Limey, the Stamp character does not kill the man partly responsible for his daughter’s death (since he comes to acknowledge, like Karma does, his own complicity). What makes this interesting is the way it refrains from the usual cathartic release of the vengeance film (i.e. like in this year’s other revenge drama, The Horseman, which loses itself in the final third and becomes a straight forward good vs. bad guy morality tale). By the end of this one, Balint comes to realize that her murderous rampage had no justification. When she and a police insider track down the man responsible for funding the whole industry Balint is shocked to see her sister alive and well; and that she has in fact willingly taken up with this rich man, who paid to have her released from her ‘contract.’ She claims to love him and pleads with her sister not to kill him. The film cuts outside, we hear gunshots, but the shift back inside reveals the shots were fired into air to fool the cop outside into thinking that she killed the man. The film ends with her at the airport on her way back home to Russia. She drops her gold cross chain to the floor. The final image is an ironic CU of the chain. We feel as empty as she does, knowing that she risked her life and took lives under a false pretence. Whereas most vengeance films have a clear outline of the moral playing field –an Old Testament eye for an eye– Sweet Karma leaves the viewer in a pensive mood after having viewed a flawed heroine’s single driving motivation cruelly taken from her.

The Impurity/Purity of WhitenessOn the other end of the spectrum is Canary (Alejandro Adams, 2009), one of the many films demonstrating the noted mise-en-scène of whiteness as visual purity, and a film which plays on the mind rather than the emotions (though there are parallels to Neighbor in that characters are left undefined). Films that featured an aesthetic of whiteness (to varying degrees of use and purpose) at Fantasia 2009 include, along with Canary, Love Exposure, Thirst, Dream, and The Clone Returns Home.

The Power of Whiteness

Dreams

Thirst

Love Exposure

The Clone Returns Home

Canary

Canary is a thinking person’s Science-fiction, eschewing the usual high tech pyrotechnics of mainstream science-fiction in favor of a subtle and ambiguous narration. The film is shot to look like a documentary, with almost constant hand-held camera and naturalistic lighting, but it is most definitely not a mockumentary. Visually it recalls, if anything, Primer and perhaps THX-1138 (two other science-fiction films which rely on an aesthetic pattern of whiteness). The film is set in the not too distant future, with pop culture references that seem contemporary, as do the cars, dress codes, etc. But the setting of a society dependent on organ transplants sets the time frame into the near future. Canary Productions, a Microsoft of Organ Transplant, seems to control all aspects necessary to the organ transplant industry. They search for donors, procure the organs medically, transfer them, and –this is where the SF extrapolation comes in– provide the necessary follow-up ‘service’ by keeping tabs on clients to make sure they follow their rigid ‘rules’ for maintaining the necessary lifestyle that ensures the transplanted organs remain healthy; The follow-up service entails an Orwellian Big Brother presence (though in an unassuming guise) observing that each client eat properly, exercise, and does not abuse their body with drugs (including caffeine); failing these measures they are contractually obligated to ‘return’ their organ. The film is played straight, in all almost disarming manner, but reaches levels of understated creepiness, like the scene where a female employee instructs a 2 year old girl, in the presence of her obliging grandparents, that she ‘do exercise’ ‘take her supplements’ and eat their ‘special cheerios’. In another client meeting, an African American teen girl is instructed in a firm tone that if she doesn’t ship up they will take back the donated organ.

After this draconian policy is established each scene between strangers takes on a menacing tone, like the post-school scene where a teacher warns a young single mother about her young daughter’s recent odd behavior (which does not seem odd to us, hence we assume the daughter is being checked on for her ‘organ behavior’). What makes these scenes especially unsettling is the omnipotent presence of a quiet (to the point of seeming invisible to all around her), young girl who works as the Canary ‘requisition angel’. The girl is dressed in an all-white, one-piece over-all which is marked by the ominous company logo (a heart with double arrows pointing in opposite directions encircling it). Though she is a major character, she never says a word, never emotes an expression, and her presence is never acknowledged by anyone (hence her invisibility). She spends two long scenes hanging around the company office (waiting for her next order?), while a dozen or so employees engage in personal talk and gossip. (There is so much overlapping dialogue in these scenes that it recalls Robert Altman on acid.)

She mysteriously appears in the home of strangers (Canary clients), lurking in the background, seemingly unnoticed, and then the scene will abruptly cut to the girl in her transport vehicle, with the said ‘stranger’ lying unconscious –but alive– next to her, as they are prepared for the organ ‘reacquisition’ (the girl uses an unassuming white lunch pail-like box and a blue gel substance that she rubs around the body where the incision will be made and/or is used to preserve the organ). In some instances we see the girl with a gas mask and spray can, which suggests that she uses the spray to make people unconscious long enough for the organ to be retrieved (but how does she gets the bodies to her vehicle?). As Craig Keller noted in his intelligent blog Cinemasparagus, the girl in white functions as a visual metaphor for the idea of surveillance: she sees everything but is never seen in return.

The film opens with the girl in her company vehicle, but with such strong backlighting and tight framing that it is hard to get a handle on what she is doing. In a gesture meant to disorient audiences, the opening scenes of the film present sets of characters in mundane circumstances speaking in foreign languages, but not subtitled (purposely). First we are at a Russian music school, then at a fast food restaurant with some Vietnamese female characters, one of whom is pregnant, and then with a German couple in their backyard. The ‘requisition girl’ appears in each of these scenes, but it is never made clear whether she is actually in the foreign country in question, or whether they are merely speaking their mother tongue in North America. The ambiguity is again intentional, setting up the possibility that the company is multinational/global, and the girl –in the most extreme case- has some sort of special powers to transport herself across space. In one arresting scene she walks around the city aimlessly, with no one noticing her, as we hear the long-winded company’s telephone answering machine message. If we think back to the office scenes and the chatty employees, we wonder why the phone call is not picked up.

Portentous eavesdropping from the ‘requisition angel’

The film ends by circling back to the girl’s vehicle, with the young mother from the after school scene lying unconscious on the floor of the van, while her daughter interacts playfully with the girl (is she even aware of what is happening to her mother?) What exactly happens to these people who have had their organs taken back? In one scene we see an ex-employee (we assume), with mental health issues, stuttering nervously through a TV interview fielding questions regarding the donors, what happens to them, etc. Nothing is ever told directly to the audience, but implied through subtle dialogue. For example, in an earlier scene a person states that people may spy on other people’s lifestyle behavior for the company; and then in the later scene where a young mother and her daughter have lunch with a third woman (perhaps the mother’s sister), the inter-dynamics around the food ordered takes on a paranoid atmosphere because we know the ‘requisition angel’ has been stalking the young mother and her daughter (in the after school exchange we see the ‘requisition angel’ spying on them from outside a glass wall in the background of the shot). The mother orders spaghetti with meat sauce for her daughter and garnishes the pasta with a heavy dose of grated cheese. The third woman comments on the amount of cheese, and tries to substitute it with some of her spinach. Within this context, we may think that this ‘third’ woman is ‘spying’ for the company or at least trying to help her sister avoid the potential of a requisition call.

Scenes follow each other without an obvious cause and effect, with straight edits used exclusively as scene transitions. For example, in one scene we see a mixed race couple, a young black teen and his Asian girlfriend chatting in the park; in the next scene they are both lying unconscious in the Canary vehicle; scenes of the requisition angel in her vehicle usually follow the ones of the ‘strangers’ (Canary customers) unaware of the fate that will soon befall them. The central locations are as follows: a board room where we eavesdrop into a Canary think tank meeting on marketing strategies; several scenes in the chaotic Canary office, some concentrating on employee chit-chat, others with clients being interviewed and instructed on company protocol; scenes between random characters who are never introduced or developed. The funniest of the latter are two young women sitting on a couch watching TV, commenting on what they are seeing and then interjecting hilarious tangents from their personal life. In all the scenes with dialogue there is a strong, off-the-cuff improvisational sense through overlapping dialogue, off the cuff asides and tangents that adds to the sense of ‘observationalism’.

Note the ‘requisition angel’ in the background

In the usual after screening chats over beer with other Fantasia attendees Canary was one of the most hotly debated films, dividing viewers into a love/hate split. I defended the film against the most common criticism of it being inchoate and meandering by arguing that these are the very qualities that lead to the sense of paranoia and mistrust that exists between the Canary Corporation and its clients, a perfect fusion of form and content. I also defended the film’s refusal to play by conventional norms of cause and effect narration and character explication. Why do all films have to abide by the same rigid rules that make a story palpable, easy to follow and resolved?

The Korean bad boy Kim Ki-Duk had one film programmed in the festival, Dream (2008), which marks a change of pace for the usually harsh Kim (with the exception of his Buddhist tale, Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter…and Spring, 2003). One of the more interesting aspects of this verging-on-the-fantastic film is its meticulous and symbol-laden art direction. A man, Jin (Jô Odagiri), is driving down the road at night and hits a pedestrian. He drives off and then wakes up in his bed, relieved that the hit and run was only a dream. Or was it? His intuition convinces him to drive to the area of his dream, where he witnesses the event actually occur in reality. When a woman named Ran’s (Na-yeong Lee) smashed car is found outside her apartment she is accused by the police of the hit and run. In a scenario that would not appear out of place in a Twilight Zone episode, Jin’s (Jô Odagiri) dream world has fused with Ran’s living reality. So that whatever Jin dreams, Ran lives out in real time in an unconscious, somnambulist state, a realist reworking of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

Although she claims her innocence to the police, stating she was home asleep when it happened, a street surveillance camera reveals her car at the scene of the accident. Jin overhears the police accusation and tries to absolve Ran of the guilt by telling them that his dream was the conduit for Ran’s crime. The incredulous policemen think he is nuts.

Jin still holds a torch for her ex-girlfriend Ran, who dumped him unceremoniously. By manipulating his new found dream powers, he is able to induce Ran, who loathes him, to sleep with him against her rational wishes. This scenario occurs whenever both characters fall asleep. So long as one of them is awake, the transference of dream into reality does not occur (sleep hasn’t been this terrifying since Invasion of the Body Snatchers). These two otherwise incompatible people are tied to each other’s minds. They find a temporary but troublesome solution: they move in and swap time sleeping, so that one of them is always awake. But when Ran is too tired to wake up and Jin falls asleep while trying to awaken her, the dream-reality switch happens again. Next solution is for Jin to handcuff Ran to his arm, but she finds the keys and escapes into their final ‘shared’ dream/reality experience: Jin’s dream of murdering Jin’s violent boyfriend. Ran is accused of the murder because of the obvious evidence that incriminates her. She is arrested and placed in a prison for the criminally insane. The final third is the film’s strength, where the forced union becomes reminiscent of The Isle (where isolation and obsession keep a couple together) and the themes take a decidedly spiritual turn. The symbols are a mixture of Buddhism and Christianity. The latter becomes most explicit when Jin takes to self-mutilation in an effort to stay awake, turning the self-inflicted pain into a Christ-like sense of sacrifice so that Ran can sleep (he smashes his feet with an iron bar, and the shot of him lying with his feet wounded has an iconic Christ-like appearance). The final scenes also draw heavily from Robert Bresson’s use of suicide as a form of salvation or escape from purgatory. After much fighting and suffering Jin and Ran acknowledge their love for each other across prison bars, recalling the ending of Pickpocket.

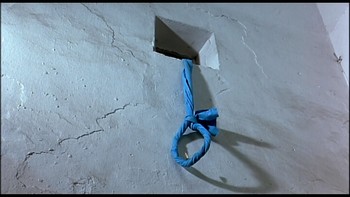

In their final moment alive together through the cell’s gates she asks him what he sees, and he replies, “a butterfly.” She swallows her golden chain with a butterfly amulet (shades of ??The Isle??’s painful swallowing of the fish hooks). Ran is locked in an all white prison room, shared with an equally mentally unstable roommate, who may be a figment of her imagination. The all-white mise-en-scène will bear extra meaning, being another link between the two souls. Although outside the prison Jin feels as equally trapped as Ran. He jumps to his death from a bridge onto a frozen sea, the snow and ice forming a similar all-white space. This then cuts to Jin’s white room, where she forms a suicidal noose with her blue bed sheet tied to the bars of the room’s only small window. Her roommate offers her back as a stool so that Jin can reach the noose. The clever editing reveals the noose where Ran’s neck was is now empty, except for a butterfly. Ran has transformed into a butterfly and with her ‘soul’ freed from the body (the prison and its bars function as symbols of their ‘outer shells’) flies to meet Jin’s fallen corpse on the frozen lake. The butterfly lands on him. When Ran feels Jin’s eyes open the shot cuts to a close-up of their clutched hands. They have been reunited. This spiritual reunification recalls the famous Chinese parable which must have been on Kim Ki-Duk’s mind when he made this film:

“I, Chuang Tsu, once dreamed I was a butterfly, fluttering between here and there, in all its aims a butterfly. I just knew that I followed my moods like a butterfly, and was unconscious about my human nature. Suddenly I awoke; and there I laid: again ‘me myself’. Now I don’t know: was I then a man dreaming I was a butterfly, or am I now a butterfly, dreaming I am a man? Between man and butterfly, there is a barrier. Crossing it is called change.”

Apparently the actor Odagiri, who is Japanese, spoke his lines in Japanese, while the actress Lee spoke her lines in Korean. Most Western viewers would of course not notice this directorial gesture, but it has thematic relevancy because the fact that the two characters do not actually understand each other but seem to converse adds a touch of the irrational into the quotidian, and is another reflection that dream is reality and reality is dream aspect of the film. There is also the often stated line in the film that “black and white is the same,” which is another way of saying that “reality and dream are the same,” or that their lives are intertwined together and hence the same (he is the black to her white and vice versa, just as they are in a same position in terms of breaking up with their respective lovers). We see this spiritual dualism in subtle elements of mise en scene, as noted by the critic on the Lunapark6 website:

The film on more than one occasion harps on the mantra “black & white is the same,” while Ran and Jin appears in contrasting black & white throughout the film. Also note the scene where Ran walks back to Jin’s car outside the Buddhist temple. When Ran peers into the tinted window, Jin’s reflection appears on the window.

Dream makes an interesting thematic link with Thirst (Park Chan-Wook, 2009) and Love Exposure (Sion Sono): three Asian films with hot auteurs all flirting in their unique way with religion and resorting to an all-white mise en scene in key final scenes. In Dream the all-white look is featured in Ran’s asylum/prison room and matched by the final resting space of her alter ego Jin, lying dead on a frozen sea bed. In Love Exposure the hero Yu Tsunoda’s (Takahiro Nishijima) rescuing of the damsel in distress Yoko (Hikari Mitsushima) takes place in the all-white headquarters of the religious cult group Zero Church. In Thirst the all-white appears at the end, in the form of the vampire’s apartment which he paints all white. You would think a vampire would do the opposite, paint it black so as to not reflect light, but Chan-Wook never does anything easy or conventional, so when I heard he was tackling the vampire genre I knew it would not exactly be crosses and garlic.

In Thirst Korean everyman Kang-ho Song stars as priest Sang-hyeon, who goes to Africa to volunteer for a medical experiment that will help find a vaccine to stave off a terrible disease plaguing the area (Emmanuel Virus). The experiment goes bad, very bad, and he dies, then returns to life after a blood transfusion. He returns with a physical malady: boils and welts turn up all over his body, but mysteriously disappear after he satiates his thirst for human blood. He begins to discover new found strengths, increased senses, and physical strength, but must curb his thirst for blood. His own blood is now ‘contaminated’ which makes him a ‘carrier’ of the vampire virus. It’s not all bad news, as he is now immortal. Unable to kill to service his ghastly thirst for blood, he lucks into a coma patient in a hospital who he uses as his personal blood bank. That is until he meets the attractive Lady Ra (Hae-ook Kim), adopted since childhood as a live-in slave to a messed up family that includes Sang’s boyhood friend Kang-woo (Ha-kyun Shin) and his wife Tae-ju (Ok-vin Kim), a domineering mother and her mentally challenged son, who she dotes on hand and foot. Kang-woon is dying of leukemia and the family successfully coerces Sang to help the family deal with their grief. Which means spending a lot of nights sitting around playing cards, gambling, and being seduced by Kang-woon’s love-starved wife. Sang begins an illicit (in many ways!) relationship with the sex/love starved Tae-ju (priests who are tempted by women to break their vow of celibacy is a theme found in Love Exposures too). Critics looking to anlayze the gender politics will point to the misogynist strain of depicting Tae-ju as the sinful Eve who seduces the priest and condemns him to inhuman acts. Before meeting Tae-ju, Sang managed to survive on the blood of the coma victim, but with Tae-ju’s encouragement he begins to exploit his powers and ends up killing for his blood. In a film noir Double Indemnity or Postman Always Rings Twice twist, Tae-ju convinces Sang to kill her husband. She becomes the femme fatale and convinces Sang to push her husband off a small boat to his death (his guilt-ridden nightmares of the husband returning from the dead are not the film’s strongest moments). They become more and more obsessively dependent on each other, and end up committing an unusual ‘forced’ double-suicide on the beach. While Tae-ju, now made into a vampire, has no qualms about her murdering ways, arguing that she is not religious and hence is in no hurry to enter an afterlife she doesn’t believe in, Sang is guilt-ridden and curbs her every attempt to hide from the oncoming rising sun (she tries to hide in the car, then in the trunk –he rips off the door– and then under the car), before they die together of sun exposure, sitting on the back of the car (a poetic and gorgeously lit sequence).

My description does not do justice to the film’s wildly inventive visual sense and abrupt shifts in tone. Park manages to mix in black humor, social analysis and vampire iconography into a volatile cocktail.

Leave it to Japan’s most adventurous auteur Sion Sono to direct a four hour teen romance, Love Exposure (2008) which ends up being much more: a satire on religious cults and religious repression, a coming of age story, a cross-dressing romance, and a lesbian love story. In a prologue we see a young boy in a happy household, until the tragic death of the boy’s mother. Before the devoutly religious mother dies she makes Yu promise that he will fall in love with “someone like the Virgin Mary” (she is holding a statue of the Virgin Mary to show him). In the voice-over of the now teenage Yu Tsunoda (Takahiro Nishijima), we learn that after her mother’s death Yu’s father Tetsu Tsunoda (Atsuro Watabe) dedicated himself to priesthood. The narrative flashes six years forward, with Yu and his Catholic priest father moving to take over a new parish. During one of his masses an hysterical woman (Saori played by Makiko Watanabe) enters his church and cries throughout his sermon, then approaches him for religious training. We learn that her apparent religious calling has an ulterior motif: to fall in love with the priest. Once she achieves her goal the priest is forced to take a second residence to live with the woman. As an internal expression of his misguided passion, the father begins to turn aggressively on his son, forcing him to confess for sins he imagines his son guilty of. When the timid Yu is unable to accommodate his father’s urge for sins he begins to act out criminal acts so as to have something to confess to his father. His father is still unmoved by his confessions, until someone Yu him that what will really disgust a priest is obscenity, so Yu joins a cult of panty worshippers and (in a scene reminiscent of the ‘training’ scenes in Pickpocket) begins to learn the craft of voyeuristic panty photography. Mixing martial arts choreography and comic timing, Yu becomes a master of the art of snapping illicit panty photos.

Cult of the Zero Church

Yu, a virgin, is still waiting for his true love, who must be someone who reminds him of the Virgin Mary. While dressed in female drag as his new alter ego the “Black Scorpion,” Yu comes across a gang about to tangle with a woman who ends up being Sairo’s step-daughter, Yoko (Hikari Mitsushima). The surly, man-hating Yoko has a vendetta against men after being abused by her step-father (in one of the over-the-top scenes she literally snaps off his erect penis while he sleeps), and takes to beating up men for fun. The drag-dressing Yu does the heroic thing and goes to her rescue. When he sees her it is love at first sight: he has found his vision of the Virgin Mary. But there are two things which make the relationship problematic, though interesting gender wise. Yoko hates men and falls head over heels in love with the women he thinks is the Black Scorpion. Hence when they kiss it is a veiled lesbian moment. Another deterrent to their relationship is the Zero Church, who enlists young female drug pusher and over-all nuisance Aya Koike (Sakura Ando) to infiltrate Yu’s household to ruin the priest’s reputation, discredit the Christian Church and hopefully increase their membership. She seduces Yoko by pretending to be the Black Scorpion. Saori conspires to arrange it so Yoko becomes, Yu’s step-sister. Koike hates Yu with a passion, but is ‘taught’ tolerance by Yu in his Black Scorpion drag voice. When Koike steals Yu’s thunder by faking to be the Scorpion, this sets Yu off into a depressive funk and admitted into an insane asylum. The all-white mise en scene of the asylum is matched by the Zero Church’s all white headquarters, invoking a parallel between faux spirituality and mental instability. The film ends with Yu escaping his hospital to save Yu from the clutches of the cult, and a distraught Koike committing Seppuka style suicide.

Yu in drag as Black Scorpion

I’ll conclude with what was the best film of the fest for me The Clone Returns Home (2009, Kanji Nakajima). The Clone Returns Home is a wonderfully poetic, intelligent, and visually sophisticated science fiction film, greatly influenced by Tarkovsky and Sokurov. The influence is felt everywhere, thematically and formally, and extends to the point of locations, sound, and shot compositions. The films that are most recalled are Mirror (mother-son relationship, use of the rural setting, the play with past/present), Solaris (the ‘returner’, the idea of a soul explored within the returner, filial love), Mother and Son (the mother/son love, the use of storm sounds, the image of the man carrying the suit (rather than mother) along dusty country roads). The film takes its central philosophical premise from Solaris where Tarkovsky uses the science of solaristics, planetary travel, and cosmology to get at what he is really interested in: a study on the nature of love (mainly between man and woman but also filial), the force of guilt, and the power of memory/the unconscious. Director Nakajima does a similar thing in using science, in this case the ethics of cloning, to deal with what is of real interest to him: memory and filial love between a son and a mother. The film’s opening shot told me all that I needed to know, setting up the film’s attention to mood through lighting, and making its aesthetic statement that the film will not be rushed. It opens on a hospital corridor, long shot looking down its glistening floor, with holy white light glaring from behind (yet another film at Fantasia 2009 that employs this visual aesthetic). A few people sit in the background. The camera slowly dollies forward then pans to the right to the seated man, then pans and dollies back. The shot runs for at least 4 minutes, and all we learn narratively is that an astronaut has died because of a human error. The main protagonist is an astronaut named Kohei Takahara (Mitsuharo Oikawa). In an early scene he is pressured by his authorities to allow his body to be cloned, in the event of his untimely death in anticipation of a dangerous mission (a death which does occur). In an interesting narrative choice, director Nakajima cuts away before we hear Kohei actually give his consent. He looks up to the ceiling high data banks and asks whether this is where all his memories would be stored, but the scene cuts away before we hear his consent. This occurs again in the later scene, after his death in space, where the same authorities, who are eager to get a legal clone approved, passive-aggressively ask his wife for consent. She is obviously very distraught, cries, and seems resistant to the idea. It cuts before she gives the audience any indication that she has changed her mind. Even after they say, “Well, ok, then we’ll give your our condolences,” using emotional blackmail to get her to consent. Even when second Kohei clone wakes up the authorities put words in his mouth, asking him if he remembers giving them the consent.

While Kohei’s mother lies ill in the hospital Kohei’s memory triggers a flashback to when he was a young boy living with his twin brother Noboru (another clone reference) and mother in a beautiful dacha setting (recalling Mirror, Solaris and Mother and Son). They live a seemingly idyllic life, with normal fraternal conflicts and warm motherly love. Tragedy strikes when the boys are out playing in a river, and a shock edit from the loud sound of the river’s rushing water to a silent overhead shot of the river implies the death of one of the boys. (The cut from noise to silence recalls the cut in Solaris from the loud highway montage to the quiet dacha). Back in the present there is another remarkable edit that establishes the odd synchronicity and doublings of this family. The wife is at the hospital with her mother-in-law. Kohei’s mother finally succumbs to her illness and dies. At her death the scene cuts to a surreally beautiful image of the dead Kohei floating in space away from the spaceship he was working from. The first clone has a memory malfunction, being reborn with the traumatic memory of his brother’s death. His guilt is all-consuming and he leaves the space lab to return to his country home, where he finds his own astronaut suit. It is uncertain whether this is real or in his mind, since the suit goes from being empty to (from his POV) having his own body within. Kohei #2 mistakes the suit for his brother, and returns to their family home, where he eventually will die and be found again by his 2nd clone later in the film. The clone is fated to repeat the primal moment when he found his twin brother dead by the river, forced to relive the grief (like Kris Kelvin reliving the pain and guilt of his wife’s suicide in Solaris).

Final Scene of The Clone Returns Home

A simple gesture that the mother would often do –running her fingers around the rim of a glass to emit the high pitched sound– becomes an aural memory and metaphor for the ‘resonance’ (the soul of the original cloned human) that the authorities say can adversely affect a clone (see Randolph Jordan’s essay in this issue for an in-depth analysis of this sound effect.). The ‘resonance’ is powerful in the first clone, but less so in the second clone, who hears it while he walks along the country dirt road, but is able to continue. The added appearance of one clone followed by another, leading to three incarnations of Kohei, reminded me of Timecrimes (2007, Nacho Vigalondo, which played at Fantasia a few years back), where the narrative space becomes filled with an additional incarnation of the protagonist because of the co-existence of different time frames.

The Clone Returns Home (gratefully picked up for North American theatrical release by Cinéasie Creatives is filled with some wonderful images, rendering a sense of tragic-poetic oneiricism unlike any film I’ve seen since Mother and Son. The constant fog and mist, recurring natural splendour, the ambient soundscape and use of silence, Kohei’s somnambulist acting and strange visions, all of these elements make it difficult to always know whether what you are seeing is happening or being remembered or imagined. For example, in one strikingly ??Mirror??-esque shot, characters at different times of their lives are represented in the same shot. In the most striking example we see clone #2 standing a few meters from his country home. We cut to his POV of his young mother, younger brother Noboru and his own older self walking from the porch through the front door. In one long shot we see clone#1 carrying the suit as if it were his brother. He collapses to the ground. A few moments later the suit rises, picks up his brother and continues the forward walk. The film ends as it begins, with a striking long take. We see the clone#2 carrying the shell of an empty astronaut suit, walking into the distance through the buck fields. The shot holds as he becomes an insignificant speck in the background.