The Evolution of “Third Cinema” in a Brazilian Context: from Santos to Bianchi

The objective of this essay is to explicate the notion of Third Cinema within a distinctly Brazilian context. Specifically, I intend to interrogate the films that emerged out of the Cinema Novo movement as such films were primarily concerned with the notions of Third Cinema, national identities, and their respective country’s political and economic structures. Through a close examination of the political messages and aesthetic strategies in a few of the major Cinema Novo works (Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s Barren Lives [1963], Glauber Rocha’s Earth Entranced [1967]), their directors’ writings, and of the works of prominent scholars on Brazilian cinema such as Ismail Xavier, Robert Stam, and Randal Johnson, I will demonstrate how the concept of a Third Cinema was articulated in these films. I will conclude with an inquiry into the evolution of the concept of Third Cinema in Brazilian cinema by discussing how contemporary Brazilian filmmaker Sergio Bianchi’s films are both in dialogue with the confrontational aesthetic of Cinema Novo and, to some extent, distance themselves from the politics of these earlier Cinema Novo filmmakers.

As the notion of Third Cinema is often elusive and broad, it is important to qualify it within the context of Cinema Novo films. Its most forceful articulation is found in Glauber Rocha’s essay “An Esthetic of Hunger” (1965) and in the leftist Argentine filmmakers Fernando Solanas’s and Octavio Getino’s essay “Towards a Third Cinema” (1969). Solanas and Getino, who made the seminal militant-activist documentary The Hour of the Furnaces (1968), were inspired by the political rhetoric of Cinema Novo. In the essay they contended that world cinema could be distinguished as first cinema (Hollywood), second cinema (European-type auteurist cinema), and Third Cinema (militant, critical, nationalistic cinema, concerned with elevating the social and political consciousness of its country’s citizenry) (Martin, p. 33-57). They called for the “dissolution of the aesthetic into the life of society” and believed that such a cinema would turn its audiences into “active shapers of their own destiny, the protagonists of their own histories/spaces” (p. 97). Such sentiments were also exhibited in “An Eesthetic of Hunger,” in which Rocha called for a turn away from classical Hollywood films and towards local production. Brazilian films must concern themselves with issues of national identity and develop their own aesthetic. Brazilian cinema, he stated, needed to be “sad, ugly…treat hunger not only as a theme but also be hungry [in its own] impoverished means of production” (95). As Robert Stam writes, “in third-worldist film theory issues of production methods, politics, and aesthetics become inextricably mingled. The idea was to turn strategic weakness-the lack of infrastructure, funds, equipments-into tactical strength, turning poverty into a badge of honor, and scarcity, as Ismail Xavier put it, ‘into a national signifier.” The hope was to give expression to national themes in national style” (100-101). A meditation on national character (identity, allegories) and the development of a radical political/cultural aesthetic divorced from the conventions of classical Hollywood/popular cinema are two significant concepts of Third Cinema present in Cinema Novo and the writings of Solanas, Getanos, and Rocha that I wish to examine here. Such concerns are at display in Rocha’s most well-known work, Earth Entranced (1967).

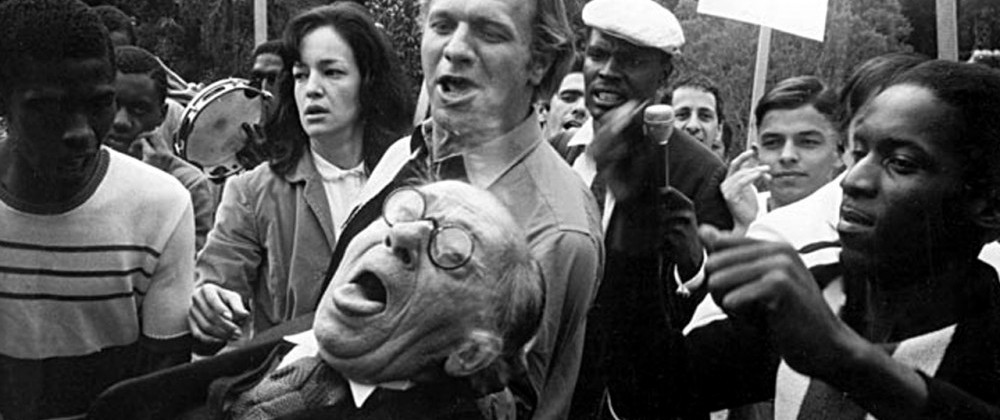

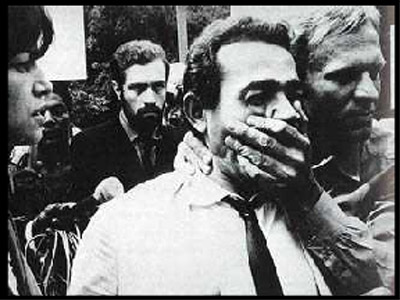

Earth Entranced

Earth Entranced (1967), an excited, bleak, and deranged allegorical satire on the Brazilian politics of the 1960s, invites numerous questions from its audience. The film is similar in style to some of the more radical works of the French New Wave, such as those of Jean-Luc Godard (Two or Three Things I Know About Her [1967], Joy of Learning [1969]). Like those films, it features stylistic tropes such as non-linear storytelling, natural settings, direct sound approach, focus on subjective experience, self-conscious style, Brechtian acting, and fragmentary break-up of narrative. What makes the films from the Cinema Novo movement different from the French New Wave’s, however, are their assaults on history. Whereas most of the French New Wave films from the 1960s distanced themselves from French history (or referred to it through philosophical abstractions), the works of Cinema Novo filmmakers, such as Glauber Rocha’s, engaged with history in a very confrontational manner. Hence, an understanding of larger issues involving Brazilian politics, culture, and mythology is key to unlocking some of the complex symbolism and allegorical allusions in Rocha’s films.

Generally, Earth Entranced revolves around a country called El Dorado (Brazil in reality) where two political leaders, one representing the right-wing and the other the left-wing opposition, battle for power. They both preside over an appallingly poor population. Paolo (Jardel Filho), the protagonist of the film, is a poet and journalist, a leftist idealist who wants to advocate for the “cause” of the masses and liberate them from their economic bondage. Most of Rocha’s main characters here are either despicably corrupt or misguidedly narcissistic, and frequently both. Diaz (played by Paul Autron) is a right-wing Christian ascetic who, with the support of the religious establishment, comes to power in El Dorado (paralleling the military coup that took place in March of 1964 in Brazil) (Xavier, p. 77) This pathologically authoritarian man is against the “savages” (the ordinary people) in El Dorado, and will make them “learn…through [his] love of force.” Diaz, we are shown, will not truly represent his people nor will he ameliorate their dismal economic conditions. Viera (Jose Lewgoy), the populist left-wing governor, is a political rival to Diaz, but turns out to be just as ineffective. He is too eager to make compromises (at the beginning of the film, he accepts Diaz’s position of power and gives up his own), avoids a civil war (he wants to “…leave the destiny of El Dorado in God’s hands”), and is also influenced in his politics by the wealthy farmers who support him. Viera fits Schwarz’s definition of many Brazilian left-wing politicians in the sixties who “…specialized in discussing the invalidity of capitalism, but took no steps toward revolution” (Schwarz, p. 132). Though there is some truth to Xavier’s assertion that Rocha, instead of aligning himself with the ideologies of the Left or the Right, is more interested in painting an expression of a fractured “…state of mind,” in showing a “…totalizing feeling of Brazil’s crisis,” it is clear that Rocha does have a distinct ideological agenda at work in Earth Entranced (1967), an agenda which can be unlocked through readings of his own political essays and through a closer focus on Paolo, a tortured and morally/politically conflicted poet and journalist whose political views and personality are much more complex than those of the aforementioned characters (who, more than anything, are shown as political caricatures).

Earth Entranced

Paolo, we realize, was at first an associate of Diaz, and later joins the “cause” of the masses and begins to support Viera as a political candidate. He even makes a television documentary on Diaz to undermine his political power by showing his lavish ways of living. He becomes disillusioned, however, when he realizes Viera’s own shortcomings. He is appalled by how Viera gives up the leftist cause and leaves El Dorado in “…God’s hands.” This disillusionment becomes painful for him at a rally in support of Viera. While circling around this cacophonous scene (where the poor dance excitedly outside Viera’s house), he questions the ignorance of the masses, who are so exuberantly supporting an ineffective populist leader. Paolo, then, comes to the foreground of this scene and directly confronts us, the audience: Are these the people, the “…illiterate, idiotic, depoliticized” masses, that we want to see in power?

This Brechtian commentary underscores Rocha’s political preoccupations. It is clear from even a cursory examination of Rocha’s writings (“An Esthetic of Hunger,” “The Tricontinental Filmmaker”) that his sympathies were with the downtrodden in Brazilian society; he empathized with their plight and was disheartened to see them suffer and starve (Bordwell, p. 437). He wanted the “…centuries of suffering and starvation” in Brazil to come to an end (437-438). This form of populism, that “…privileged the movement from the top to the bottom,” needed to be deconstructed (Xavier, p. 90). The masses were often ignorant and aligned themselves with leaders such as Viera who had turned Brazil in to a country of “…reconciliations” (Rocha, p. 79). A true esthetic of violence, of hunger, could only be ignited through a form of consciousness which corresponded with a “…level of structural social awareness appropriate to truly revolutionary attitudes” (Xavier, p. 83). The “paternalistic” populism of leaders such Viera, as Paolo acknowledges, would lead the masses to nowhere as it only contained empty words, and was driven by charisma, rather than a genuine political will.

For Rocha, then, the goal of the Cinema Novo movement and Third Cinema was to create such a form of social awareness for the downtrodden, specifically poor Brazilians whose debilitating poverty had alienated them from the larger political processes. This form of awareness could only be created through the kind of radical cinematic forms and techniques employed in Earth Entranced (1967); radical political content would serve no use if presented in conventional narratives. The jarringly surreal editing techniques in this film, which make ambiguous leaps from myth to reality (a shot of people dancing ecstatically to Samba music followed by a shot of someone lying dead on the street) and its Brechtian acting techniques (actors, as in much of Godard’s work, do not so much act as passively read out lines which seem to come out of cultural and political manifestos) were a way of making the audience part of this political process. This process must not only be contained within the film, it needed to reach out to the spectator as well. This, then, is what Rocha believed was the distinct strength of Third Cinema films such as Earth Entranced (1967). He believed that his films could instill within their viewers the social awareness and knowledge of the workings of political and government institutions which necessarily precede correct political action. This assaultive, carnivalesque collage of sights and sounds aimed to jolts its viewer into a heightened state of political awareness and social insight.

Barren Lives

Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s spare, perturbing Barren Lives (1963) concerns a family of four, a couple and their two children, trying to survive in the sertao, the poverty-ridden, semi-arid region in Northeastern Brazil. Just as Earth Entranced [1967], Barren Lives (1963) is considered a seminal work of Cinema Novo/Third Cinema and, just as that film, it too is concerned with illuminating the socio-cultural realities of Brazil through its unconventional narrative, harsh aesthetic, and modest means of production. Glauber Rocha suggested in his essay “History of Cinema Novo,” that Cinema Novo was not an aesthetically homogenous movement (Martin, p. 293). Rocha was correct in his assertion that Cinema Novo directors employed different stylistic techniques (although as Stam writes, such techniques almost always had nothing to do with conventional [Hollywood] classical forms and mostly drew on “innovative” currents such as surrealism, cinema verite, minimalism, Brechtian epic theater, the French New Wave, etc.) (Stam, p. 99). Yet it is indisputable that that these films were made in the service of one over-arching cause: to awaken the political (leftist) and social consciousness of the Brazilians (Martin, p. 86). Fernando Birri, in “Cinema and Underdevelopment,” wrote that this could only be accomplished by showing Brazilians a true image of themselves (93). Doing so, he believed, would create a consciousness of “reality” (94). This, then, would be a cinema that would penetrate the “darkest” corners of Brazilian life (Johnson and Stam, p. 33). These filmmakers, through their own writings and interviews, eloquently articulated the political and ideological agendas and the subjects of their films. What is more intriguing is how they approached and directed these subjects. For as Rocha acknowledged, it was not merely enough to make films about the poor and the destitute in the Brazilian society. A consciousness of reality could only be awakened through the kinds of radical cinematic forms and techniques employed his own films such as Black God, White Devil (1964) and Earth Entranced (1967), and those of other Cinema Novo filmmakers such as Nelson Pereira dos Santos. The film’s austere, minimalist aesthetic perfectly complements the bleak lives of the characters at its center. Through its narrative pace and characterizations, the film wants the viewer’s experience to be “dry,” so as to serve as a reminder of the actual conditions under which some Brazilians lived in such a landscape (126).

Barren Lives

Like Luis Bunuel’s Los olvidados (1950), although through a more exacting method, Barren Lives (1963) de-dramatizes and de-sentimentalizes the four main poor characters. Fabiano (Atila Irio), his wife Sinha Vitoria (Maria Riberio), and their two children are silent through most of the film. So preoccupied are they with surviving that they do not have the time or energy to engage in long conversations. As Johnson observes, the characters generally communicate in “…gestures, grunts, and monosyllables” (121). Certain viewers’ conventional dramatic expectations are also continually thwarted, most notably through Fabiano’s stoicism and general passivity. The first time he goes into town (the family lives on a desolate farm), he is cheated by the landowner and harassed by the tax collector; the second time he visits the town, he is tricked into joining a card game which results in his subsequent arrest and beating by a soldier (122-123). When Fabiano is offered to join a jagunco’s (a bandit) band (who treated his wounds in the jail), he flirts with the idea. When released from prison, we have a shot of him sitting on the jagunco’s horse, holding a rifle. The film does not turn into a vigilante fantasy, however. Fabiano simply refuses to proceed further and returns to his family (123). He is a taciturn man who stoically endures all the injustices that come his way. In a later confrontation with same soldier in the woods, he thinks of killing him with his dagger. Yet again, he remains composed and gives the soldier the asked-for directions to a nearby road (“The end of the trail, to your right.”).

The film’s narrative pacing is in sync with the desolate lives of its characters. Much of the plot is revealed to us through long, “monotonous” shots (Martin, p. 286). The most prominent one is the very first shot. It is static, lasts four minutes and has the four characters and their dog Baleia walking the parched land in blistering heat, slowly approaching the camera. The shot sets the tone for what’s to follow. The camera languorously observes the unhurried, quotidian rhythms of this family’s everyday life. It is precisely in its “fidelity” to the rhythm of its characters’ lives that Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s film derives its distinct strength (Johnson and Stam, p. 126). The form and the content of the film are often indissoluble. If the goal of Cinema Novo filmmakers was to awaken the spectators’ consciousness of reality through novel, unconventional narrative techniques (as Rocha believed it was), then Barren Lives (1963), at least to this viewer, succeeds in doing just that. Not only is the film about Brazil’s darkest corners and the lives of its poorest citizens, it becomes, through its spare, minimalist rigor, about the time as it is lived by those citizens.

Barren Lives

Cinema Novo’s highlights Barren Lives (1963) and Earth Entranced (1967) both embodied a certain vision of Third Cinema. This vision, however, was not to last for very long. “The third-worldist euphoria of the revolutionary 1960s,” Stam observes, gave way to “…the disenchantment triggered by the collapse of communism, the frustration surrounding the hoped-for “tricontinental revolution,” the realization that the “wretched of the earth” are not unanimously revolutionary (nor necessarily allied to one another), and the recognition that international geopolitics and the global economic system have obliged even socialist regimes to make their peace with transnational capitalism” (Stam, p. 281).

Sergio Bianchi is a contemporary Brazilian filmmaker who, to a certain extent, retains the anarchic spirit of Cinema Novo in his work, who still sees in the concept of Third Cinema some “tactical and polemical use for a politically inflected cultural practice,” and yet remains critical of the political idealism and dogmas of previous thinkers and filmmakers such as Rocha and Santos (Stam, p. 291). Sergio Bianchi’s films also foreground marginalized groups in order to expand and complicate the discussion around the notion of a Brazilian national identity. Through his films, from Twisted Fate (1979) and Romance (1988) to the recent controversial Chronically Unfeasible (2000), Bianchi continually examines issues related to environment, gender/sexuality, race, immigration in a very confrontational manner (his films often include assaultive, Brechtian interludes asking audiences questions about Brazilian society –about its racism, homophobia, extreme poverty– that many would rather not confront). While Brazil was making its transition to democracy and free elections in the 1980s (after being under a repressive, military rule since the mid 1960s), Bianchi, through his aggressive, impolite films, was offering Brazilians views of geographic, cultural, and economic displacement and (unlike the Cinema Novo films) addressing issues of gender and sexuality (Martin, p. 306). Romance (1988), one of his most debated films, is about a left-wing journalist Antonio Cesar whose death haunts his two formers lovers (Andre and Fernanda) and a young journalist (Regina) who is determined to find out the cause of his death. There are rumors that Antonio may have died of AIDS. This rumor becomes a constant source of frustration and anxiety for Andre, Antonio’s former boyfriend, who suspects that he may have been infected by the disease. The paranoia and fears surrounding the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, homophobia, and the stigmatization of gay men are a few of this politically audacious film’s central themes. The film shows Andre having numerous frequent sexual encounters with other gay men in public spaces. His physical contacts tend to be frustrating, fleeting, compulsive, and stem from a sense of social alienation and loneliness. Bianchi’s film then is in part about the sociology of gay male desire in this particular moment in Brazil’s history. Like the aforementioned Brazilian films, Bianchi’s films are also concerned with the exclusion of the country’s indigenous populations from the country’s civic and economic prosperity. In a telling scene, Regina is riding in a taxi on a highway. The film interrupts and steps out of its main narrative and switches into a documentary mode: for the next few minutes, the audience is given a journalistic account of the displacement and exploitation of the people who were removed from their lands as a result of this highway’s construction.

His other films have frequently employed similar tactics. In Twisted Fate (1979), his surrealist first feature, an eccentric woman addresses us, the audience, with her extra-diegetic gaze and remarks that “…the immigrants are the backbone of Brazilian power…and when they turn the Amazon into toilet paper and typing paper, there’ll be no air left.” In What Is It Worth? (2005), another character reminds us that it is neither the left nor the right that makes the Brazilian democracy function adequately. The unchecked “…freedom to consume,” we are informed, is what makes “…democracy truly work” in contemporary Brazil. At one point in Should I Kill Them? (1982), Bianchi’s notorious short-film, the screen goes blank and the narrator facetiously inquires about the number of Native Brazilians left in Brazil. “How is it,” the audience is asked, “that a tribe surviving in the late 1950s has been reduced to a single member in the 1980s?,” thus making it confront some of the excesses and abuses in the name of industrialization in the country.

As we have seen, Bianchi’s films are similar to Cinema Novo films in their engagements with some of the Brazilian society’s most deplorable contradictions especially as they pertain to issues of class, race, and (more so) sexuality and gender. They also seek to raise their viewers’ political and social consciousness through their charged confrontation and honest interrogation of such issues. Yet at the same time, the films’ attitudes toward the role of the political intellectual/filmmaker are somewhat different than the ones at display in the films and writings of Cinema Novo filmmakers such as Glauber Rocha. Larrain argues that that re-installation of democracy in Latin American countries such as Brazil paradoxically led to the relative de-politicization of the state because, as previously suggested, it led to “…wide agreements between formerly antagonistic political forces” for the sake of a democracy which implied a wide-range of “possibilities for debate and participation” (Larrain, p. 16). In the words of Randal Johnson, implicit in some of the early works of Cinema Novo was the “…romantic vision of the [usually leftist] artist (auteur) as possessing a superior form of social and cultural knowledge as well as a self-attributed mission for making the people aware of their alienation…as a means of helping them overcome their weaknesses and use their strengths to find solutions to their problems” (Martin, p. 386). Even the Left’s subsequent actions, informed by a need to search for “…allies in the moderate camp in response to neo-liberalism and perestroika,” and part of a “pragmatic convergence” based on a need to re-establish democracy,” contradicted some of its 1960s political convictions (Carr and Ellner, p. 7-9). Antonio Cesar, whom we only see through television clips, is a Rocha-type radical leftist intellectual screaming about the injustices of the Brazilian economic system and his attempts to expose corruptions in an important business deal. Antonio’s voice no longer has the same resonance in this new Brazilian democracy which, after years of brutal repression, has become more concerned with political reconciliation and civic cooperation. (At the end of the film, Regina gives up her investigation and joins the government in establishing a small museum to honor Cesar’s intellectual outputs and legacy; his anarchic/leftist politics become subsumed under the rubric of democratic/civic development.) Till its very end, Bianchi’s film remains skeptical toward the “Manichean,” romantic fantasies and myopic leftist ideals of figures such as Cesar, Rocha, and Santos (Stam, p. 282).

I began this essay by interrogating the aesthetic and political strategies of Cinema Novo filmmakers such as Rocha and Santos, directors whose films articulated the tenets of Third Cinema film theory especially as it was espoused in essays such as “An Esthetic of Hunger” and “Towards a Third Cinema.” As we have seen, disillusionment with a certain brand of leftist politics and the re-installation of democracy in Brazil in the mid-80s turned “Third Cinema” into a somewhat “anachronistic” label in that country (Stam, 291). One filmmaker who has carried on such a tradition is Sergio Bianchi. Bianchi shares with certain Cinema Novo filmmakers the belief in the importance of urgently examining the socioeconomic issues facing one’s society, often through “aesthetic innovation” (282). However, unlike their films, his films shows that such political discussion and action must not remain confined within the limits of “appropriate” discourses (leftist, rightist, etc.). His “Third Cinema,” even as it aims at raising social and political awareness, ambitiously wrestles with the perpetually evolving, unfinished, and (often) elusive project of “national” progress.

Chronically Unfeasible

Bibliography:Birri, Fernando. “Cinema and Underdevelopment” pp. 86-94 in Martin, Michael T., ed. New Latin American Cinema, Volume One. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997).

Bordwell, David, and Kristen Thompson. Film History: An Introduction. (Columbus: McGraw-Hill, 2009).

Carr, Barry, and Steven Ellner, eds. The Latin American Left. (Boulder: Westview Press, 1993).

Getino, Octavio, and Fernando Solanas. “Towards a Third Cinema: Notes and Experiences for the Development of a Cinema of Liberation in the Third World” pp. 33-58 in Martin, Michael T., ed. New Latin American Cinema, Volume One. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997).

Johnson, Randal and Robert Stam, eds. Brazilian Cinema. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995).

—-. “Transformation of National Allegory: Brazilian Cinema from Dictatorship to Redemocratization” pp. 295-322 in Martin, Michael T., ed. New Latin American Cinema, Volume Two. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997).

—-. “The Rise and Fall of Brazilian Cinema, 1960-1990” pp. 335-364 in Martin, Michael T., ed. New Latin American Cinema, Volume Two. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997).

Larrain, Jorge. Identity and Modernity in Latin America. (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000).

Pick, Zuzana M.. “The New Latin American Cinema: A Modernist Critique of Modernity” pp. 298-311 in Martin, Michael T., ed. New Latin American Cinema, Volume One. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997).

Rocha, Glauber. “History of Cinema Novo” pp. 275-294 in Martin, Michael T., ed. New Latin American Cinema, Volume Two. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997).

—-. “An Esthetic of Hunger” pp. 59-61 in Martin, Michael T., ed. New Latin American Cinema, Volume One. (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997).

Schwarz, Roberto. Misplaced Ideas: Essays on Brazilian Culture. (New York: Verso Books, 1992).

Stam, Robert. Film Theory: An Introduction. (Malden: Blackwell Publishing, 2000).

Xavier, Ismail. Allegories of Underdevelopment: Aesthetics and Politics in Modern Brazilian Cinema. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997).

Filmography:Los olvidados (dir. Luis Bunuel, 1950) 80 min.

Barren Lives (dir. Nelson Pereira dos Santos, 1963) 103 min.

Black God, White Devil (dir. Glauber Rocha, 1964) 120 min.

2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (dir. Jean-Luc Godard, 1967) 87 min.

Earth Entranced (dir. Glauber Rocha, 1967) 106 min.

The Hour of the Furnaces (dir. Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas, 1968-1970) 260 min.

Joy of Learning (dir. Jean-Luc Godard, 1969) 95 min.

Should I Kill Them? (dir. Sergio Bianchi, 1982) 34 min.

Romance (dir. Sergio Bianchi, 1988) 103 min.

Chronically Unfeasible (dir. Sergio Bianchi, 2000) 101 min.

Twisted Fate (dir. Sergio Bianchi, 1979) 75 min.

What Is It Worth? (dir. Sergio Bianchi, 2005) 110 min.