All the Colors of the Dark vs. They’re Coming to Get You

When it comes to Italian popular cinema, there has already been quite a bit written on some of the not inconsiderable differences that exist between domestic (for the Italian market) and International releases of the same film (my concern is with the North American market). Some of the more notorious examples are the films by Mario Bava and Dario Argento, which have been re-edited (and in some cases rescored and re-dubbed) for a whole range of reasons, including violence, nudity, and adult themes (sexual situations, necrophilia, homosexuality, etc.). Some of the more notorious cases are Black Sunday, the US release of The Mask of Satan, which replaced the original score by Roberto Nicolosi with one by Les Baxter [1] (as well as editing the film for violence, pacing, etc.); Black Sabbath, the US version of Bava’s I tre volti della paura, which rearranged the order of the three stories and eliminated the lesbian content of one of the episodes (“The Telephone”); The House of Exorcism, the US version of Lisa and the Devil, which is ostensibly a different film, with major reshoots of exorcism scenes to capitalize on the popularity of The Exorcist; and Dario Argento’s heavily censored US releases of Tenebre (Unsane, shortened by over ten minutes), Deep Red (The Hatchet Murders, shortened by about 5 minutes), and Phenomena (Creepers, shortened by 28 minutes!). These have all received ample coverage in the post-Tim Lucas Video Watchdog era, so I would like to concentrate on a film which has received little explication with regards the differing versions, Sergio Martino’s All the Colors of the Dark (1972), released in North America by Independent International as They’re Coming to Get You (1975). The film was also released in the US under two alternate titles: Day of the Maniac and Demons of the Dead. According to Adrian Luther Smith’s invaluable Blood and Black Lace: The Definitive Guide to Italian Sex and Horror Movies (Stray Cat Publications, 1999), the French release title was Alliance Invisible_/_The Invisible Alliance, a second France/Belgium release title was De bonte ontucht_/_Toutes les couleurs du vice_/?_All the Colors of Vice (p. 119).

I had first scene a 16mm print of a North American version in 2002 and had written a review of it for Offscreen. A few years later I purchased the uncut Italian version on DVD and watched the film a second time. The film seemed different but I could not pinpoint the differences because the memory of the first screening was vague. When I recently had the chance to review the 16mm print of They’re Coming to Get You I took good notes and immediately went to the DVD to look for the differences, and what a revelation it was. Having seen the two versions in rapid succession I can now see that the changes between the uncut Italian version and this truncated print version place a completely different emphasis on the film, shifting it from a giallo film with touches of the horror (supernatural) filone (and a more coherent plot), to a supernatural film with touches of the giallo filone.

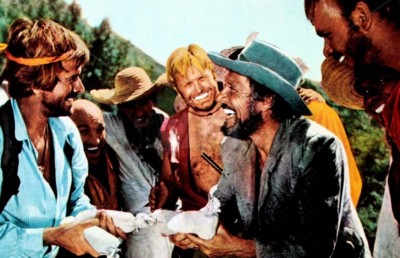

To quickly summarize the general plot, Jane (Edwige Fenech) is a young woman suffering from post-traumatic stress after miscarriaging due to complications of a car crash. Her sister Barbara (Susan Scott / Nieves Navarro) blames the accident on Jane’s live-in lover Richard (George Hilton), who was driving the car at the time of the accident. Jane’s growing sense of neurosis seems to be getting worse: she is unable to engage in sex with Richard since the car crash, suffers from bizarre nightmares (great cinematic set-pieces) which feature a blue-eyed killer (Ivan Rassimov) and a surrealist (i.e. symbolic) merging of two traumatic events in her life: the murder of her mother and her miscarriage. Richard and Barbara have different remedies to Jane’s psychological problems: Barbara wants her to see a top London psychiatrist whom she works for, Dr. Burton (Jorge Rigaud), and Richard –who thinks the doctor is a Freudian quack– wants to cure her with medication (a green potion) from a pharmaceutical company her works for. Her blond-haired, possibly lesbian neighbor Mary (Marina Malfatti) introduces a third remedy: seeking ‘liberation’ (sexual? feminist?) by joining a Satanic coven which, she claims, helped her out of a similar emotional trauma.

Jane begins to see the character from her nightmares, Mark Cogan (a menacing Ivan Rassimov), following her everywhere she goes. The imposing man is ultimately revealed as the sabbat’s lieutenant. The cult, led by J.P. McBrian (Julian Ugarte), introduces Jane to a world of incantations, orgies, and animal/human (Mary) sacrifices (murder). Jane is hospitalized after a near fatal attack by Mark Cogan (Cogan is stabbed to death with a pitchfork by Richard seconds before he is about to stab Jane). Jane is sequestered from her hospital room by the coven leader McBrian, acting as a police commissioner, and is taken back to the coven’s castle where she is seemingly murdered. The uncut Italian version continues from this point on with several extra minutes, including a repeated scene which establishes Jane’s powers of premonition (the first instance of this scene is then perceived as a foresight). Equally important, the film concludes with the police revealing (in pure giallo style) that the Satanic cult was merely a cover-up for a drug ring, and Richard pushing J.P. McBrian off a rooftop after a chase and struggle.

In Video Watchdog No. 39 Tim Lucas estimates that about 5 minutes of footage was removed from the US version and notes four major scenes that have been removed:

1) the opening main titles 2) the opening nightmare sequence…. 3) a scene following Mary’s death, in which Jane awakens outside the manor and is led back inside by Rassimov, who shows her the blood on the floor to prove that it [the sacrificial murder of Mary by the coven] wasn’t a nightmare; and, most importantly, 4) a scene in which Richard Steele is revealed to be having an affair with Jane’s sister Barbara (Susan Scott)…who is also revealed as a coven member, and whom he shoots during a kiss, before she can shoot him (p. 8).

My estimate based on the print that I saw is that there are closer to eight or nine minutes missing from the North American version, and leads me to conclude that there are (at least) three extant versions of the film: the completely uncut original Italian version, which has been restored to DVD by Shriek Show/Media Blasters; the version cited by Lucas which was released circa 1975 in North America, but which may have also circulated in Italy for its subsequent runs; and a third version, the print I saw, which includes the cuts Lucas cites, plus further cuts which I will discuss later.

The cuts, to varying degrees, rob the film of style, atmosphere and subtext. I’ll outline some of the ways over the following paragraphs. The US release is missing the opening pre/credit scene, an atmospheric, static long take of a wooded area, which starts at dusk and then slowly turns to night. The transition from day to night is achieved optically and as it gets dark we begin to see colors that were not present in the day: oranges, purples, and browns.

This of course relates to the title, and also foreshadows the later key scene in a similar park, where Mary introduces Jane to the liberating idea of the witch’s coven (frame still to the right, below).

The quiet scene can also be read metaphorically as a mirror of Jane’s mind: as the film progresses it becomes clear that Jane’s (Edwige Fenech in one of her best performances) own mind has many ‘dark colors,’ including powers of seeing into the future or being able to see events that have not yet happened.

The US version includes only a few short shots of the surreal dream sequence (lasting a few seconds) and then cuts to Jane waking up from a nightmare. The Italian version includes the lengthy post-credit dream sequence in all its wild glory. The manically edited scene, intercut with rapid camera movements/zooms, features a panoply of odd characters set against a black background: large pregnant woman lying on an operating table, legs spread; an old, girlishly dressed lady who moves about mechanically like a doll; and a younger woman who looks like Fenech also on a bed being stabbed by a tall, blond, blue-eyed man (Ivan Rassimov). The dream sequence ends with a series of negative images and a point of view shot of a car driving headfirst into a tree. All of this seems very bizarre and disconnected, but makes sense if interpreted in ‘Freudian’ terms. The art design recalls, somewhat, Dali’s own surrealist landscapes for Hitchcock in Spellbound. Later in the film we discover that Jane is suffering emotional and mental trauma from a car accident, driven by her common law husband Richard, which led to a miscarriage. Employing dream logic which can only make sense to the dreamer or an analyst fully aware of the patient’s life history, the imagery is symptomatic of what is troubling Jane. The dream mixes the car accident and a completely distinct incident which occurred when Jane was about 7 years old, the violent murder of her mother (we later learn, at the hands of the drug dealers disguised as Satanists). The image of the pregnant woman with wild frizzy hair and the bloodied belly is a clear indicator of her abortion/miscarriage. The mechanically gyrating old lady/child doll can be read in one of two ways. When the Rassimov character stabs the pregnant woman (assaulting the camera) the shot cuts to this doll figure falling backwards as if she were the one felled by the blow. This could make her a representation of the miscarried child that would have been or, in fact, a representation of Jane as a young girl, witnessing the murder of her mother. In whole, this sequence, which lasts just under two minutes in the uncut Italian version, adds considerable nuance to Jane’s character and the relationship between her and Richard.

In one of the scenes between Jane and her analyst Dr. Burton (Jorge Rigaud), Jane reveals that Richard does not know about her mother’s murder, and that Richard believes the problems they have been having sexually are tied up wholly to her accident, but she confides that it is not the accident that is stopping her from having sex, but the murder of her mother. Tellingly, after her initiation rites in the sabbat, where she has sex with the high priestess J.P. McBrian, in the caressing presence of the pseudo lesbian Mary, the scene confuses place and time by cutting from Jane in the heat of passion at the sabbat to Jane making love with Richard. The scene eventually settles at Jane’s apartment, with Jane and Richard appearing quite relieved that things are finally back to normal in their bedroom, but Jane is not convinced that she has passed the final hurdle, or that their new found happiness is anything but short-lived. This is not the first time the film/Jane’s mind confuses the image of Richard with Brian, as it occurs again in the hospital scene, described later, and opens the possibility that Richard and the high priestess of the coven, J.P. McBrian, are indeed manifestations of the same character in Jane’s mind.

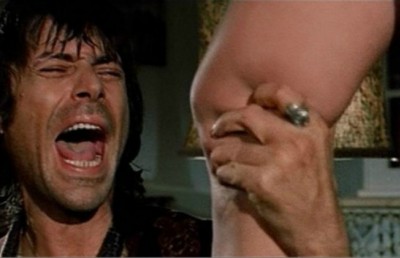

The other important scene cut out of the US version is the one between Jane’s sister Barbara and Richard, which comes right after the scene where Richard saves Jane from an attack by Mark Cogan. This scene runs from 78’45” to 82’45” on the DVD and is important for several reasons. The scene confirms what we suspected in an earlier scene where Barbara undresses in plain view of Richard: that they have had sexual relations and that Barbara is part of the sabbat (she has the coven sign on her wrist). Barbara tries to seduce Richard into joining the sect, but when she pulls out a gun and they embrace it is Richard who shoots her dead. He then throws a letter at her fallen corpse saying that he knows why she wanted Jane dead, implicating her in the threats against Jane. At this point we assume that there is a monetary reason behind the threats to Jane. This scene cuts straight from a close-up of Barbara’s lifeless face to Jane waking up in an all-white hospital bedroom, yelling out the name, “Barbara.”

What this implies now –and which will be confirmed retroactively– is Jane’s premonitory powers: she has awoken from a vision/dream of what has just transpired in another location, Barbara’s murder. Without the previous scene of Barbara’s death, her cry makes little sense.

The film continues with a knock on Jane’s bedroom door. The orderly answers and we see McBrian asking if he can see her. The orderly tells him she can’t be disturbed at the moment. The fantasy/dream nature of this scene is hinted at in the visual style, which is given an overexposed hue and shot partially with a distorting wide angle lens. The image of McBrian seen from Jane’s POV begins to alternate with a kaleidoscopic montage of Jane’s face and Richard’s face. It flips back and forth between them before resolving to the face of Richard, who is now standing by her bed asking if she hears him. Richard secrets her away from the hospital and takes her back home. The elevator in their apartment building –which has been depicted throughout the film as a foreboding space– seems stuck at a higher floor, so Richard walks up to investigate. Jane waits downstairs with a worried look on her face. She hears a pained yell from above and runs up the stairs to find Richard lying on the ground, wounded in the chest, with the camera panning from Richard’s blood-soaked sweater to Jane holding a bloodied dagger in her hands. In an instance, police, press, and an ambulance arrive to take away Richard’s body. The people barging into the area all have the tell-tale coven sign on their wrists, implying a large conspiracy, or paranoia on Jane’s part (a la Rosemary’s Baby). McBrian takes Jane back to his manor to take part in another black arts ritual. He moves toward her with a knife in his hands –much like Cogan does in the nightmare scenes and in the ambiguous (is it real or imagined?) tour de force home invasion scene– and thrusts it into her. The image pauses into a freeze frame and is treated to a solarization effect. The North American print which I viewed ends here, in an abrupt fashion.

The original Italian version continues on past the apparent death of Jane for another six minutes and gives a completely different meaning to the film. Rather than dying at the priestesses’ hands, Jane wakes up once again in the hospital to Richard at her bedside and a police officer is in the room with them. Jane tells Richard that she doesn’t know if she is awake or dreaming, which reflects the twist. This leads into the revelation scene, where Jane and Richard are taken to the police station and shown photos of the people involved in the coven as being part of a drug ring. They claim to have found her heroin addict neighbor Mary’s body buried in the castle cellar with other victims. They are told that the high priestess J.P. McBrian is still at large, and that Barbara had committed suicide and that she was, “The real diabolical one of the sect. She exploited their rites for her own criminal purposes.” However, we know the police’s comment about Barbara’s suicide to be wrong, since we saw her being murdered by Richard (at least in the uncut version). Richard remains deceptively quiet throughout this scene, as does Jane, which sets up the film’s fascinatingly ambiguous moral conclusion. The solicitor Clay (played by bug-eyed, Peter Lorre look-a-like Luciano Pigozzi, who viewers may remember from Bava’s Blood and Black Lace and Baron Blood or Margheriti’s Seven Deaths in the Cat’s Eye) enters the scene to give some exposition. The Clay character was seen in one other brief scene on the telephone speaking with Jane. Clay tells Jane that the man who murdered her mother had died months ago in New Zealand and left an inheritance of 600,000 pounds in the name of her and her sister. What is odd here and never explained, is how Mark Cogan (Ivan Rassimov) can be the visualization (in her dream) of her mother’s murderer, since this happened when Jane was seven years old and Cogan seems the same age now as in her nightmares (blame it on dream logic). The solicitor also told Barbara about the inheritance, which is why she tried to get Jane killed: to claim the inheritance all for herself. This revelation shifts the plot away from the supernatural to a more common giallo explanation of greed and money.

We now cut back to the repeat ‘déjà vu’ scene of them entering the tenement and Richard going up to investigate the stuck elevator. Jane now understands her own insight, “Oh my God, I’ve already lived this moment,” and runs up after Richard. This is a very innovative gesture, akin to the repeat at the end of Invaders from Mars where the boy wakes up from his dream only for the dream to unravel in reality all over again. Or the end of Dead of Night, but it is slightly different here because the plot continues forward.

As Martino explains in the interview on the recent DVD release, this decision to repeat the scene was ahead of its time and was cut out by the distributors because they felt audiences would have been confused by the repetition: “When the women [Jane] finally gets to the elevator in her apartment, first she experiences what would have happened and then, with the experience of her imagination, she is able to survive and save her husband in reality. However, this dream sequence was cut out by the distributors because they felt it would confuse the audience. They felt it would look like the projectionist had replayed the same scene!” [2] Martino goes on to clarify that this dream or premonition scene was intact when first released in Italy, and only after some audiences may have expressed confusion over the repeated scene did the distributors edit out the dream sequence for future releases. Martino guesses that the dream sequence may have been excised only for future Italian releases, and not international releases, but the copy I have seen would suggest that it was also cut out (along with other scenes) from future international (or at least North American) releases.

As the scene continues we now see McBrian at the top of the landing attempting to kill Richard. McBrian seems to be acting out of revenge for Barbara: “You killed Barbara and you must die.” McBrian runs up to the roof with Richard in pursuit. As in many giallo, the villain falls off the roof to his death. The film ends with Jane and Richard embracing near the edge of the roof, with Jane offering a final dialogue which is anything but reassuring. She tells Richard that she knew all along that he killed Barbara and that McBrian was going to try and kill him in the elevator. “Oh Richard, I’m afraid. I’m afraid of not being myself anymore. Help me.” As the camera dollies in to Richard, his mouth bloodied from the scuffle with McBrian, he turns toward her with an intense look on his face. The film ends on a freeze frame, with the end credits starting. I can see why the US distributor would have cut all this out. Having the hospital/elevator scene repeat may have been confusing for giallo audiences of the early 1970s, but more damning is its moral ambiguity. What will Richard do? He has already killed three people. Knowing what he does now, will he throw Jane off the roof to make sure he remains clear of any murder charges? The cut version casts the Richard character in a better light because he is no longer implicated sexually with his partner’s sister, Barbara, nor has he killed anyone. George Hilton’s role in the Italian version is disarmingly ambiguous and far from the more heroic character he appears to be in the US version. Mikel Koven elaborates on this moral ambiguity (common to the giallo) in his excellent (and, as the first book on the giallo in English, I’d say groundbreaking) book La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Cinema:

But it is the actions of Jane’s partner, Richard, that begin to complicate the presumed polarity between “good, normal people” and “evil, wicked Satanists”: in protecting Jane and himself from the coven’s clutches, he murders just as many people as Mark. Richard kills Mark with a pitchfork, shoots Jane’s sister Barbara (Susan Scott) dead for also being a member of the coven, and ends up pushing the coven leader off the roof. If Richard kills just as many people as the coven does, what is the difference between the two? It is true that Richard does not torture puppies, but he is having an affair with Barbara while her sister is recovering from losing their baby, and then he ends that relationship by shooting her. The film vilifies witchcraft as an evil practice, but the actions of the supposedly heroic characters undercut that moral certainty (p. 113).

Also, with Jane admitting that she knew Richard killed Barbara what do we make of her behavior? Although her voice seems to express genuine apprehension over her powers of second sight (“Oh Richard, I’m afraid. I’m afraid of not being myself anymore. Help me.”), we must also wonder why she didn’t speak up at the police station. Did she keep quiet to keep Richard out of trouble? Or to ensure that she would keep the full inheritance? Or both? Not exactly noble actions.

Along with issues of narrative coherence, as reiterated by Martino, the reason why the North American version ends with the abrupt death of Jane at the hands of the Satanists no doubt also has to do with what the distributors thought would work best for their market. Ending the film by having Jane murdered by the Satanists heightens the demonic angle, which likens the film even more to Rosemary’s Baby (which even the uncut Italian version owes some debt to). My guess is that US distributors were doing as much as they could to capitalize on the successes of Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist.

To summarize, based on the many plot synopsis’ I have read of the film, I think there are (at least) three extant versions of the film: the completely uncut original Italian version which showed theatrically in its initial run and which has been restored to DVD by Shriek Show/Media Blasters; the version cited by Lucas which was released circa 1974-1975 in North America, but which may also have circulated in Italy for its subsequent runs; and a third version, the print I saw, which includes the cuts Lucas cites, plus further cuts that lop off four major scenes after Jane is taken back to the coven by J.P. McBrian: 1) waking up again in the hospital 2) Richard and Jane taken to the police station and informed of the drug/criminal ring and her inheritance 3) the repeat of the tenement scene, only now with J.P. McBrian attempting to kill Richard, and 4) the subsequent chase to the rooftop, struggle between Richard and J.P. McBrian, the eventual death of McBrian from the rooftop fall, and the final rooftop embrace between Jane and Richard.

Regardless of the many reasons for the differing versions of All the Colors of the Dark (economic, aesthetic, industrial, market demands), the uncut Italian version remains the truest to the giallo filone which was a mainstay of the Italian popular cinema since the mid-1960s, in at least four senses. Firstly, whereas the US version establishes without a doubt the reality of the Satanic cult, the Italian version holds out the possibility of a subtler, ambiguous narrative which is more in keeping with the giallo. For example, the possibility that much of what we see (the Satanic cult scenes, the random appearances of the Mark Cogan character) is a figment of Jane’s neurosis gets more aesthetic treatment in the uncut Italian version, including the confirmation of Jane’s ‘second sight’ (which is completely removed in the truncated North American ‘3rd’ version). In this respect All the Colors of the Dark belongs to that handful of gialli dealing with female neurosis (The Lizard in a Woman’s Skin, Stendhal Syndrome). Secondly, the revelation of the ‘cause’ for the murders being materialistic (greed, money, inheritance, etc.) rather than supernatural is much more in keeping with the conventions of the giallo. Thirdly, the Italian version brings back into the fold the notion of detection by having a detective (amateur or professional, in this case professional) explain/solve the crime. On a more trivial note, the fourth sense has to do with the manner in which the killer dies: being pushed off the roof. Koven notes that this is a common way for the giallo villain to die: “…one of the most popular is throwing the killer off of a cliff or other high place. This method of death seems to be a metaphoric “fall,” whether echoing Satan’s fall from Heaven [most appropriate in this film, given that McBrian is the high priestess of a Satanic sect], or our fall from Eden” (p. 107).

Endnotes

1 In Tim Lucas’ magnus opus he writes that Sam Arkoff’s reason for this was because the original score was, “too Italian” (All the Colors of the Dark, Cincinnati, Ohio: Video Watchdog, 2007, p. 313).

2 “All the Colors of the Dark: Sergio Martino.” DVD Features. Media Blaster Inc., 2004.