Chopsocky Slapstick: Violence as Humorous Excess in the Kung-Fu Comedy

From Jackie Chan to Stephen Chiau

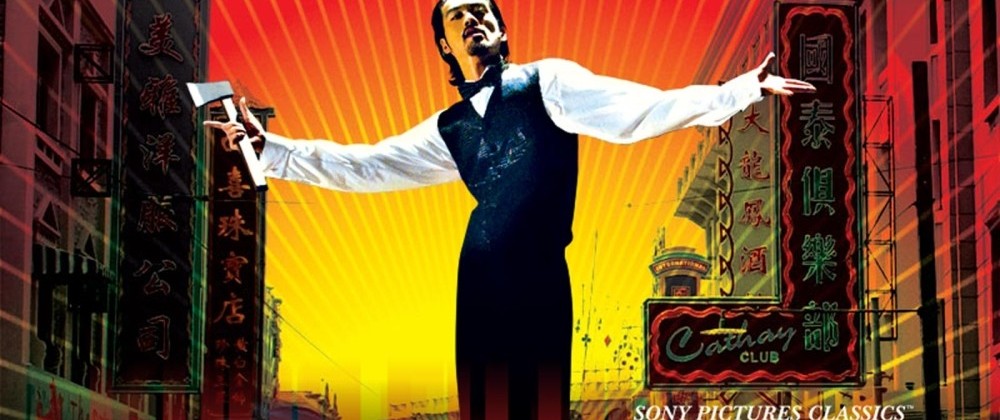

When Stephen Chow’s most reverent satire of the traditional Chinese wuxía pian (“martial chivalry film”), Kung Fu Hustle (2004), was shown at the Sundance Film Festival, Roger Ebert’s knee-jerk reaction was to draw similes between Jackie Chan, Buster Keaton, Quentin Tarantino, and Bugs Bunny in an effort to describe the hybrid form this Kung-Fu comedy assumed. The slapstick-laden wuxía free-for-all seemed to be a further refinement in Chow’s blossoming reputation in North America, celebrating his self-reflexive fusions of parodic Kung-Fu films woven together with his penchant for wit and inter-textual satire, and a reinvigorating approach to the critically marginalized genre itself. Chow’s particular brand of action-comedies provided a refreshing perspective into an entire mode of Chinese filmmaking, which, by Chow’s assessment, North Americans have long misinterpreted. Frequently dismissed as excessively violent and banking on vacuous spectacles of combat and martial finesse rather than profound and/or compelling characters and plots, Chow sees this perspective as limited and half-formed. Rather, he confesses, “it may sound strange, but the martial arts are not about making war. They’re about honour — and hopefully, not making war.” [1] Indeed, Ebert concurs with this misplaced emphasis on violence in Kung-Fu films as a dead end rather than a means of overcoming severity and the critical insistence on unity and narrative coherency. “Lurking beneath the surface of most good martial arts movies is a comedy” [2] is the aphorism Ebert asserts in his review of Kung Fu Hustle, and in so doing unearths the foundation of not only Chow’s repertoire, but of the very essence of the Kung-Fu comedy in Hong Kong’s cinematic history.

In an effort to distill the essence of his unique strategy, Chow breaks down the three fundamental tools he employs as a filmmaker –action, comedy, and comedy [3]– and by combining these he has been able to re-imagine both the Kung-Fu and Comedy genres in Hong Kong’s film industry while crafting his own personal style. However, Ebert’s preliminary comparisons, shared by the press reviews used in the film’s North American promotional material, falsely imply the need to anchor Kung Fu Hustle??’s international form to its Occidental counterparts as if this intermingling of Classical American Slapstick and Hong Kong wuxía pian were original or unique to ??Kung Fu Hustle, as if Chow were the first Chinese auteur to stumble upon this formula. In truth, Chow is only the most recent Hong Kong filmmaker to seize upon the paradoxical proximity between traditional Kung-Fu film form and the Vaudevillian-esque slapstick mode, continuing the subgenre which finds its prenatal roots in King Hu and Liu Jialiang’s proclivity toward humour in their wuxía pian, and which finds fruition in the farce and clowning of Karl Maka, Sammo Hung, and Jackie Chan. By consulting both the history of Hong Kong cinema and the mutual necessity of “excess” in both Kung-Fu and slapstick film, we can derive the essence of both cinematic modes as grounded in the absurdity of discordant discourses, which are brought to the surface of Hong Kong cinema in distinction from mainland Chinese cinema and therefore illustrative of the Hong Kong cinematic character.

In stark contrast to the Mainland Chinese film industry’s stubborn history of minimizing commerce with the Western world, Hong Kong’s filmic history is deeply entrenched in internationalism and consequentially resists the national unity enforced by the People’s Republic of China board of censorship. Hong Kong cinema has instead sought to define the nation-state’s cultural identity by articulating itself in opposition to “various political and ideological-linguistic positions and aesthetic orientations,” both internally and “vis-à-vis the mainland mentality” (Fu and Dresser 1-2). This antagonism across ideo-linguistic and cultural discourses stems from the composite identity inherent to Hong Kong’s cinematic and cultural history of bisecting Cantonese and Mandarin cultural and linguistic modes cast beneath the umbrella of British rule. In fact, one of the earliest exposures to film production in Hong Kong was in 1898, when The Edison Company commissioned cameramen to document the urban landscape of the city-state, the same year the British signed the 99-year lease on Hong Kong first stipulated in the Treaty of Nanjing over fifty years prior. [4]

Over the years, Hong Kong’s cinema would vacillate between Cantonese and Mandarin languages as the lingua franca of its film industry, owing to the stop-start beginnings of the local industry. The Lianhua Production and Printing Company’s formation through Hong Kong finances in 1930 and its subsequent reallocation to Shanghai only one year after precipitates a recurrent pattern in between the film industries of Hong Kong and the mainland. The influx of Shanghai filmmakers in 1938 during the Japanese invasion of China acted as a catalyst for both technical prowess and Mandarin dominance in Hong Kong cinema, but quickly came to an end when the island was finally occupied by Japan in 1941. [5] The Diaspora of Cantonese-speaking emigrants throughout Vietnam, Malaysia, and the U.S. who fled Hong Kong during the occupation in turn reinstated a demand for Cantonese-language productions after the war, only to be again thwarted by the mainland Chinese Diaspora fleeing the totalitarian measures taken by the People’s Republic of China and its recklessly executed Cultural Revolution. It was not until the American Kung-Fu fervor of 1973 that Cantonese-language Kung-Fu films would be reinstated as the standard in Hong Kong cinema.

Beyond this realm of internal tension and contention between “northern” and “southern” Chinese culture lies the presence of the foreign market as a significant contributing factor to the profound quantity of production in the film industry. The city’s population alone was in no way large enough to sustain a local film industry prior to the 1970’s, and therefore was “almost exclusively export oriented” [6] – an economic necessity which would explode with the American obsession with the low-budget, kitschy films released by Warner Brothers, such as Five Fingers of Death (1972), The Big Boss (1971), and Fists of Fury (1972), launching the Hong Kong Kung-Fu genre to international notoriety and cementing its affectionate position within film history. This surge in Western popularity, largely in part due to Bruce Lee’s transnational presence in both the Oriental and Occidental industries, tinges the genre with a tertiary language of English dubbing, and therefore positions it between yet another cultural paradigm which further dilutes a unified Hong Kong cinematic identity. [7]

Through these opposing discourses of Mainland Mandarin traditions, Guangdong’s Cantonese culture, and the ravenous Western economic interest, it becomes difficult to disagree with Fu and Dresser’s deduction that “Hong Kong presents a theoretical conundrum” (5), that it confounds conventional means of ascribing a “national” quality to a particular film industry. Thus, instead of defining Hong Kong’s cinematic identity within the boundaries of a national cinema, Fu and Dresser astutely diagnose the films of Hong Kong as conforming more so to a postmodern construct, “a transnational cinema, a cinema of pastiche, a commercial cinema, a genre cinema, a self-conscious, self-reflexive cinema, ungrounded in a nation, multiple in its identities” (5). Accepting this untraditional designation, we can adopt Bruce Lee as a synecdochic figurehead for the Kung-Fu genre and Hong Kong’s cinematic landscape itself – born of Chinese and Eurasian decent, cultivated internationally, produced domestically, and celebrated internationally. Therefore, before even directly addressing the Kung-Fu comedy subgenre, we can acknowledge the industrial context itself to be inextricably formulated along contrasting modes and structures of cinematic representation, interpretation, and most importantly, re-interpretation. Hong Kong’s cinematic identity is not and cannot be one of unity, not elemental but compound, defined by how it defines other structures yet resisting any unified definition itself.

As a result of the material constraints placed upon the industry through its need for mass-production to sustain its foreign markets, the Kung-Fu films of the 1970’s featured expressly shoddy production values and cinematography, especially when compared to the more theatrical and intricate wuxía pian of the previous decades. [8] Almost all films used post-synchronized sound, employed the anamorphic camera inexpertly (leaving edges of the frame unfocussed and producing washed out colours), and characteristically abused the zoom lens as a cheap solution to complicated camera movements, generating the signature camp-quality to technical composition of Kung-Fu films from this era. In Li Cheuk-To’s discursive analysis of the production quality of 1970’s Hong Kong cinema he notes this revised perspective on the economy of filmmaking in the Shaw Brothers Kung-Fu productions as typified in the use of the long-take in order to exploit the “pro-filmic event,” or the intricate choreography and physical ability beyond the fight sequence itself. This strategic employment of the long take reflected that the Shaw Brothers’ concerns were “no longer for ‘drama,’ but to document ‘spectacles’”(A Study in Hong Kong Cinema 131).

The importance of the “spectacle” in the construction of the Kung-Fu film is essential to its popularity, with the fight sequence featuring as a paramount element in any Kung-Fu export. Any and all Kung-Fu films preceding and following this period necessarily included extensive and lengthy spectacles of martial arts proficiency, functioning as a conditio sine qua non to the Kung-Fu genre in much the same way graphic sexuality forms the essential basis of pornography. These fight scenes could be indispensable to the narrative progression, such as Zhi Shan’s defeat at Pai Mei’s hands in the prologue of Executioners From Shaolin (1977), or virtually superfluous, like in The Fearless Hyena (1979) when Shing Lung’s Grandpa reprimands him for arrogantly making a spectacle of his Kung-Fu knowledge in a punitive duel. These Kung-Fu spectacles formed a large portion of the attraction to the genre in America, where audiences across racial boundaries found “the dubbing and excessive mayhem food for giggles” (Fu and Desser 22) beyond the realm of social and psychological poetic realism, as was the status quo in Communist Chinese productions of the time.

Western critics found this emphasis of the spectacle over the dramatic in the genre contemptuous, with one reviewer from Variety lamenting, “that sheer violence remains as potent at the b.o. as … sheer sex” (qtd. in Fu and Dresser 23), dismissing the films as cheap commercial products rather than genuine artistic artifacts. This view of spectacle as inferior to narrative is not uncommon to Western film criticism, which often perceives the material aspects of films which cannot be subordinated to a unifying story or thematic development as miscalculated and suggestive of poor cinematic form which seemingly overlooks the need for all aspects of films to adhere to narrative meaning. These fight sequences are entertaining only in their materiality; their presence, though frequently instigated by the narrative, proceeds beyond the efficiency of narrative progression and flies directly in the face of classical views on the economy of the story. They are unnecessary interludes that do not conform to the totality of the film’s plot and meaning, but are rather self-contained narrative elements that proceed incongruously to the narrative. Their merit is exactly what frustrated Western critics: they are excess, irreconcilable with stories yet compelling nonetheless.

In her article “The Concept of Cinematic Excess,” Kristin Thompson elaborates on the concept of “excess” as initiated by Stephen Heath and Roland Barthes, the latter preferring the term “obtuse meaning” to define the tertiary rhetoric which emerges as a result of the insurmountable materiality of the photographic image which “goes beyond the narrative structures of unity in a film” and “arises from the conflict between the materiality of a film and the unifying structures within it” (qtd. in Thompson 55). This excess manifests in the purely visual components of the film which do not colour the story, but are physical manifestations which allude to impressions, or even their own self-contained narrative, which cannot be integrated into the overarching narrative discourse. They may be initiated as a necessary point in the plot, but through their duration can betray the functionality of their intended function. This breakdown is undeniably integrated into the Kung-Fu fight sequence, which emerges from the story but through their extended duration reveal that they are in fact examples of excess par excellence. Why is it that these particular attacks and defenses must be used in this particular order in this particular film, and not in any other Kung-Fu movie? It is for this reason that Kung-Fu fanatics can, and often do, evaluate and compare films based on their fight sequences alone: they can be extracted from the narrative freely and reviewed outside of their own narrative context. They exist as a new story, or a new temporality, within and beyond the temporal construct of the temporality that contains it. [9]

In the same way that Kung-Fu excess was marginalized as superficial and unsophisticated, pure forms of slapstick comedy has received a similar treatment in film criticism in the Occident. Donald Crafton takes up this same idea of cinematic excess as a means to liberate classical Hollywood slapstick from the need to subordinate slapstick gags to the linear progression of the narrative and the continuity of the story. Crafton takes arms against the popular view that “slapstick is the bad element, an excessive tendency that narrative must contain” (Karnick and Jenkins 107), overturning the idea that classical slapstick filmmakers intended to “integrate” the excess of slapstick into the narrative, and that its occurrences were calculated disruptions of narrative continuity which embraced the dissonance between horizontal and vertical expansions of the story. Crafton’s analysis even extends to Brett Page’s description of the vaudeville sketch, which presciently echoes Thompson’s first deconstruction of the contingency of form in the excess image: “It points to no moral, draws no conclusion, and sometimes might end quite as effectively anywhere before the place in the action at which it does not terminate. It is built for entertainment purposes only and furthermore, for entertainment purposes that end the moment the sketch ends” (qtd. in Karnick and Jenkins 109). With this in consideration, it is certainly difficult to deny that the essential structures that generate amusement and entertainment in Kung-Fu films and slapstick comedy are composed of the same ingredients, if not the same structures altogether. This is why it is often difficult to stifle impulses to laugh when we watch Donnie Yen punch his opponent fifty times in three seconds in Ip Man (2008), or when Bruce Lee swings two Karate fighters around by their garments in Fists of Fury: they are excessive, and as soon as they step over line of what is reasonable and sensible, they (briefly) divorce themselves from the logical and enter the realm of pure spectacular excess.

Slapstick’s indulgence of the materiality of the image over its psychological or ethical coherency takes to heart Harry Langdon’s formula that the essence of comedy “is the concentration on the physical, as opposed to the spiritual” (234) and pushes this equation ad absurdum. The violence in slapstick comedies (and wuxía pian) is distinctly surreal in its presentation, and regardless of how severe the degree of violence, “slapstick accidents are mainly survivable,” and moreover, “the worse it gets, the harder we may laugh” (Dale 15). In fear of entirely overlooking the presence of the spiritual, slapstick’s materiality is significant precisely because it confounds the existing narrative (intellectual, moral) quality of the story. Dale perceives this relationship acutely, stating that “slapstick has its own secular sense of the soul enclosed in the body that only holds it back … the central irony is that the hero’s body itself comes between him and the satisfaction of his physical desires” (14).

Though Dale’s analysis falsely extends the domain of slapstick into physical, situational, and even cringe comedy, it is in this fundamental irony that he returns the spiritual as an inseparable factor in the emphasis of materiality. The image’s excess is only excessive in its incongruity with the story; its excess materiality is only funny in its ironic existence. Thus, when he proclaims that slapstick is indeed representative of an existential condition, [10] he rightfully connects the low-brow comedic mode to high-brow philosophy. The very nature of physical excess which stands in the way of an absolute teleology is manifest in the slapstick comedian’s constant encounter with himself as an impediment to dramatic satisfaction, to the coherency of meaning he seeks in spite of his own physical obstacles. Within the heart of the simplest icon of slapstick humor, the banana peel, “the very refuse of his own eating left upon floor,” [11] we find constantly the comedian’s encounter with himself as the other, whose existence serves no unified purpose but is rather simply there to confound the unity of rationality.

This alien confrontation with the physical self conjures similes to Jean-Paul Sartre’s La Nausée, and his protagonist Antoine Roquentin’s encounter with his own hand:

I see my hand spread out on the table. It is alive – it is me. It opens, the fingers unfold and point. It is lying on its back. It shows me its fat under-belly. It looks like an animal upside down. (qtd. in Priest 22)

Sartre’s ontological view of reality (both personal and objective) strikes home when held next to Thompson’s breakdown of excess. Roquentin’s nausea is motivated by a direct encounter with the contingency of existence – the character himself admits, “the essential thing is contingency. I mean that, by definition existence is not necessity” (qtd. in Priest 22). In Sartre’s philosophy, above all else one must first recognize that existence, and therein any individual who exists, is superfluous, or “de trop,” as he writes. It is at its basis excessive, unnecessary and separate from any grand narrative or teleological coherency. Like the Kung-Fu fight scene or the slapstick gag, the prima materia of existence itself does not conform to any inherent meaning and is therefore in-itself excess.

While Sartre and his Western contemporaries followed in the vein of the Weeping Philosopher Heraclitus by reacting in despair and nausea to the absence of meaning in existence, Zen Buddhist perceptions of the superfluity of existence mirror Heraclitus’ maxim that “the upward and the downward path are one and the same” (Russell 25), responding that anyone searching for the “way upward … will hit it by descending lower” (Hyers 82). However, where Heraclitus attempts to create a static model of flux and the interdependency of binary opposites, Zen mentality encourages its practitioners to embrace the commonplace and the trivial, the thing-in-itself (material and contingent), and by opening their mind to the mystery and inexhaustible significance one can attribute to it (irreconcilable, incongruent meaning), awaken to the totality and transcendental ontology beyond the physical and intellectual properties of the object. [12]

Just as the spiritual is inseparable from the physical for Dale, Zen philosophy demands the acceptance of both the tathat¬ã (concrete “suchness”) and the sunyata (“the Void within and beyond that image”). [13] The Void “within and beyond” the image is central to Zen, who perceive this formlessness “in very positive, dynamic, creative terms, and emptiness is the most appropriate designation for the ultimate reality and basic truth of all things” (Hyers 89). This absurd derivation of totality from nothingness is what distinguishes the Zen approach from the Western perception of nothingness and meaninglessness, where absurdity is perceived not as an obstruction or detraction from enlightenment, but as a comical tautology “that precipitates laughter… that moves beyond alienation and anxiety into a joyful wonder” (Hyers 97), revealing the comic spirit inherent to Zen mentality and actualized by the existence of Zen clowns. These enlightened clowns guided others to this humorous transcendence “through riddles and enigmas, through nonsense and insults, … through slapping, kicking and striking, … almost as if one were watching … an ancient Oriental version of the slap-stick characters in a Marx brothers’ film” (Hyers 42). Slapstick and Kung-Fu’s non-rational manifestation, therefore, cannot be a “bad element” or an “excessive tendency,” but an integral tool which leads to enlightenment.

This is not an assertion that Zen mentality as a conscious and intentional element in Slapstick and Kung-Fu film, but rather as a commensurable basis for the two modes to touch base upon and to assert a prior consciousness of excess as comical in both “cinemas of attraction”. This absurdity is the appeal and humorous fountainhead mutual to both genres, which channels laughter as both a release from intellectualization and anxiety, as well as an appreciation of the excess of the physical and its inclination to frustrate meaning and unity by conforming the logical mind to the absurdity of existence rather than the other way around. This fundamental ontology of excess is the reason why both slapstick and Kung-fu sequences incite first suspense, fear, and anxiety of the physical violence, which is then confounded by the superficiality (anti-realism) of the image that transforms these sensations into exhilaration and humor.

With this understanding of the basic mechanics that conjoin the Occidental and Oriental structures of amusing excess, we can turn back to the Kung-Fu comedies, which instigated this discursive analysis to begin with. Though we can decipher the presence of slapstick comedy innately bound to even the most dramatic Hong Kong Kung-Fu films, there are indeed certain stylistic and formal quotations which surface in the Kung-Fu comedies of the late 1970’s that blatantly allude to Western attitudes, and even particular schticks, that appear in Classical Hollywood slapstick comedies.

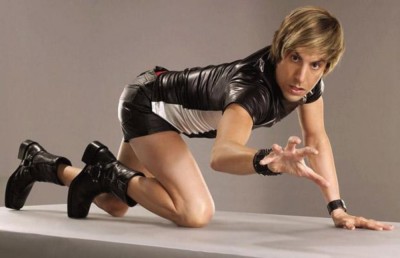

Though Jackie Chan cannot in good faith be declared the progenitor of Kung-Fu/Comedy fusions (Tony Wayns notes King Hu and Liu Jialiang share “a marked inclination towards comedy” [A Study in Hong Kong Cinema 51]), or even of the Kung-Fu clown archetype (Sammo Hung beat Chan to the punch (pun intended) by one year with The Iron-Fisted Monk [1977]), his first excursion into the genre, Drunken Master (1978), is unique in its minimization of self-reflexive parody, as well as its blatant allusion to the comic Zen Master in both Chan’s clownish performance and in the drunken antics of Sua Hua Chi. Karl Maka and Sammo may have preceded Chan with their satires and parodies of the conventions and forms of Kung-fu films, but films such as Enter the Fat Dragon (1978) or Dirty Tiger, Crazy Frog (1978) derived their comedy from the reorganization of structures typical of the Kung-Fu genre, introducing situational comedy and wit into the non-combative portions of the film (such as comedic commentary in the soundtrack, replete with slide whistles and laughing brass instruments), with minimal instances of slapstick comedy within the fight sequences themselves. [14]In short, Maka and Sammo’s films are more conceptually based, revealing self-reflection and intersecting discourses in the narrative’s construction, whereas Jackie Chan’s Kung-Fu comedies seem to have internalized this self-awareness and the collision of Kung-Fu and slapstick modes as physically enacted in the fight sequences themselves.

Drunken Master (1978) distinguishes itself from Maka and Sammo’s Kung-Fu comedies by its integration of the gag into the combat itself, better approximating the styles and forms taken by slapstick comedy in the American tradition. In the first part of the film when Wong Fei-Hung’s father bequeaths the rest of the lesson onto his goony assistant, the mischief Wong and his friend enact on the hapless substitute teacher is bound within the context of a Kung-Fu class, but barely constitutes martial arts, with the assistant hitting the friend’s hand to make him slap himself, Wong and accomplice’s teasing jabs and slaps, and the assistant’s sudden strike to punish the mistaken culprit (04:00 – 07:13). This is clearly an example of playful violence which not only provides excess material to the narrative of the film, but also excess material to the overall discourse of the Kung-Fu genre. When the frustrated assistant finally challenges Wong to a fight, Wong’s fighting style is less than pragmatic, often tripping, slapping, bopping, tumbling, and taunting his opponent more often than actually sparring. He even goes so far as to point out the assistant’s right foot, only to stomp on his left foot (complete with extra-diegetic spring sound effect). This “fight sequence” shares more in common with the Three Stooges’ intricately choreographed mayhem and roughhousing than with the Shaw Brothers’ regular fare of Kung-Fu films. [15] In beating down the pompous substitute teacher, Chan insures that a sense of play is inextricable from the combat itself, mocking the formality of the assistant’s Kung-Fu and placing a properly executed kick on par with punching your opponent in the butt several times as equally valid attacks.

Chan’s particular brand of Kung-Fu comedy differs from Sammo and Maka’s in his treatment of the excess quality of Kung-Fu fight sequences as compared to theirs. Sammo and Maka certainly acknowledge the combat in the wuxía pian as excessive spectacle, and attempt to reconcile the absurdity behind the form by adapting the narrative structure to allow for this “excess,” which, now reconciled, really ceases to be excessive. Enter the Fat Dragon plays on the absurd and exposes the protocol of traditional Kung-Fu films by openly displaying them within the character’s motivations, which in turn propel the story. In Drunken Master and Chan’s self-directed follow-up, The Fearless Hyena (1979), Chan, unlike Sammo and Maka, does not attempt to expose the patterns of Hong Kong Kung-Fu films by wedging comedy into the narrative, but rather exposes the essence of the two by drawing comedy out of the spectacle of the combat itself. In this manner, where Sammo and Maka conceptualize and intellectualize the seemingly irreconcilable modes of comedy through irony and pastiche, Chan descends deeper into the mundane and low-brow modes of Kung-Fu and comedy in order to find “the way upward”.

The self-reflexivity of Chan’s films lies in making a spectacle of the spectacle, acknowledging that, while the Kung-Fu fight sequence is in-itself excess to the film’s narrative, it is tied to a larger discourse within the history of the genre itself. What Chan introduces is a secondary aspect of excess, the slapstick gag, into the already excessive display of Kung-Fu as a means of laying bare the modes of its production. By toying with the substitute teacher’s hat in Drunken Master and by drawing out a slap in The Fearless Hyena, Chan makes a spectacle of the excess itself, exposing that it is not simply the moments of blatant slapstick, but the Kung-Fu itself which is humorous. Much like the Tramp boxing in City Lights, Chan is able to ring the bell to stop and start the action from within the boxing ring in order to disrupt the unity of the match and bring forth the humour within and beyond the violence.

Chan set the precedent for Kung-Fu comedy with these films, which Stephen Chow eventually seized upon with his directorial debut, King of Destruction (1994), however his personal style of utilizing the tools of action, comedy, and comedy revealed his preference for the latter element over the prior. King of Destruction??’s style of Kung-Fu comedy is closer to Sammo and Maka’s, being far more conceptually absurd and playing into parody of not only genres, but of particular films themselves, such as Ho Kan-Am’s introduction which makes a farce of ??Terminator 2: Judgment Day (time code: 04:35 – 5:30). This style of farce falls into the self-aware style of Kung-Fu comedy that Enter the Fat Dragon perpetuated, and the few elements of slapstick are often placed outside of the fight sequences (such as when Ho Kan-Am leaps over a railing, is hidden by a passing bus, which moves away to reveal his intense sprint has ended in a sudden tumble, (time code: 18:27 – 19:05) or in the interim between (when the hazardous “distractions” Devil Killer throws in the air during the match are revealed to have impaled several of Ho’s trainers) (time code: 1:23:10 – 1:24:58). The absurd move that Ho makes his signature attack, in the Invincible Wind and Fire Wheel, presents the closest example to clown-like Kung-Fu in the film, though it only appears twice in the entire movie (time code: 44:30 – 45:15; 1:34:35 – 1:34:40). Ultimately, King of Destruction is a parody of the modes that compose conventional Kung-Fu films, as well as a parody of their American progenies like the Karate Kid series, and not an example of true Kung-Fu/Slapstick fusion in the manner that Chan founded.

Even up until Shaolin Soccer (2001), the comedic form Chow employs remains anchored to the unlikely marriage of film genres –with this film in particular he aligns the narrative discourses of the underdog Sports film and the Shaolin-lore based Kung-Fu film. Kung Fu Hustle then, does deserve the distinction that Western critics gave it, but not for its original integration of Slapstick comedy into the mythical wuxía pian, but rather for its return to the Slapstick Kung-Fu which Chan developed almost thirty years before. Early in the film when the Axe Gang captain goes to hit the barber with his hatchet and is mysteriously kicked out of the frame, only to be revealed later in a camera movement to be head first in a barrel far off in the background, teetering around from the momentum of his fall, the simultaneous presence of Kung-Fu and slapstick excess can be perceived (time code: 18:00 – 18:30). The Axe Gang captain’s trajectory begins by superhuman kung fu, and falls back down into the realm of the comic. By the end of the film, stomping on toes, twisting an opponent’s arm like a rubber band, and twirling that person about an even number of times become acceptable Kung-Fu attacks and defenses, blurring the boundaries between the two.

Returning to Ebert’s original aphorism, “lurking beneath the surface of most good martial arts movies is a comedy,” it becomes evident that it is this realization that has motivated the last few decades of Kung-Fu comedies, but it is in the Kung-Fu genre’s appropriation of slapstick mentality where the filmmakers assert that the two are one and the same. In the same fashion that Hong Kong cinema itself is a national cinema unto itself composed of various intersecting ideo-linguistic discourses, the Kung-Fu comedy simultaneously utilizes two contrasting modes of violent excess to deter the persistent need in the spectator to make sense of all the elements within the film, encouraging them rather to laugh at the absurd spectacle-in-itself as a means of relinquishing intellectual obstinacy and appreciating the totality of the Void. When Chow aligns himself with this approach in Kung Fu Hustle, he puts himself in league with slapstick clowns dating further back than Chaplin and Kung-Fu buffoons of the late 1970’s, working within an industrial climate sustained by self-reflection and the demands of foreign markets. Kung Fu Hustle is certainly not the first wuxían pian from Hong Kong to feature a blend of zany slapstick and Kung-Fu action, but is rather the culmination of a rich and inevitable history of the Kung-Fu slapstick film.

Endnotes

1 Monk, Katherine. “Kung Fu Films: Not Just an Excuse to Show Action.”

2 Ebert, Roger. “Kung Fu Hustle”

3 Monk, Katherine. “Kung Fu Films: Not Just an Excuse to Show Action”.

4 Fu, Poshek and David Dresser. The Cinema of Hong Kong p.13

5 Noted by David Desser in Fu, Poshek and David Desser. The Cinema of Hong Kong p. 31-32

6 ibid, p.1

7 Interestingly, in Tarantino’s revival of Pai Mei in Kill Bill: Volume II (2004), he insists on sustaining this tripartite language, having Pai Mei speak Cantonese, and The Bride responding in either Mandarin or English.

8 A Study of Hong Kong Cinema of the 1970’s p.130-131

9 “You will have another temporality, neither diegetic nor oneiric, you will have another film” – Barthes quoted in Thompson, Kristin. “The Concept of Cinematic Excess” p.56

10 Dale, Alan. Comedy is a Man in Trouble p.11

11 William Faulkner quoted in Comedy is a Man in Trouble p.11

12 Hyers, M. Conrad. Zen and the Comic Spirit p.83

13 ibid, p.89

14 Enter the Fat Dragon (1:07:22 – 1:07:35) reveals one particular exception when Lung goes to hit a cowering opponent, but then tugs on his nose in classic Three Stooges style.

15 The Fearless Hyena (10:46 – 11:00) Chan goes so far as to copy Moe’s tactic of fluttering his hand back and forth as his victim watched it in order to draw out the suspense of the slap.

Works Cited

Dale, Alan. Comedy is a Man in Trouble: Slapstick in American Movies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000. Print.

Ebert, Roger. “Kung Fu Hustle”. Chicago Sun-Times 22 April 2005. Web. 6 December 2009.

Fu, Poshek, and David Desser, eds. The Cinema of Hong Kong: History, Arts, Identity. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Print.

Hong Kong International Film Festival. A Study of Hong Kong Cinema In the Seventies: The 8th Hong Kong International Film Festival. Hong Kong: Presented by the Urban Council, 1984. Print.

Hyers, M. Conrad. Zen and the Comic Spirit. London: Rider and Company, 1974. Print.

Karnick, Kristine Brunovska, and Henry Jenkins, eds. Classical Hollywood Comedy. New York, London: Routledge, 1995. Print.

Langdon, Harry. “The Serious Side of Comedy Making.” The Silent Comedians. Metuchen, New Jersey & London: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 1993. 233-235. Print.

Monk, Katherine. “Kung Fu Films: Not Just an Excuse to Show Action”. The Vancouver Sun 25 April 2005: C6. Web.

Priest, Stephen, ed. Jean-Paul Sartre: Basic Writings. New York: Routledge, 2001. Print.

Russell, Bertrand. Wisdom of the West. Ed. Paul Foulkes. Yugoslavia: Crescent Books, Inc., 1949. Print.

Thompson, Kristin. “The Concept of Cinematic Excess.” Ciné-Tracts 1.2 (1977): 54-63. Print.

_400_258_90_s_c1.jpg)