Bruce Lee: Authorship, Ideology, and Film Studies– Part 2

As discussed at length in Part I of this essay, over the last several decades, there has been virtually no diversity within the field of Bruce Lee Studies. The fact that the academic discourse on Lee consists entirely of supratextual deconstruction of his cinematic indexicality has created a sphere wherein there is an egregious imbalance in analytic focus. Even in the best textual analyses of Lee’s film work [1], there is still looming over the exegeses the presence of the dominant critical orthodoxy as produced by the cultural studies colonization. Moreover, the vicious paradox of Bruce Lee Studies in assessing its place within film studies is that one of its most serious impediments is Lee’s considerable popularity/familiarity. As Hegel warned, the familiar, because of its very familiarity, can at times be taken for granted as sufficiently understood. [2] Because of the popularity of Lee and his films, Hong Kong film festivals, action/martial arts festivals, university screenings, and the like often times do not even bother showing his films, an affronting practice enabled by a lack of objections which signifies an acquiescence to the tacit implication that everybody has already seen his films and everyone already knows everything there is to know about them, ostentatious and unsophisticated as they are. [3]

It is much more acceptable for academic activity involving martial arts cinema to focus on the work of King Hu, the only martial arts filmmaker of the era to be accepted by the film studies community as a “legitimate” auteur. [4] Only Bey Logan and John Little have gone out of their way to praise Lee as a skilled filmmaker, with the former noting the delicacy with which Lee visually structured his fight with Chuck Norris in The Way of the Dragon (Logan, 2006) and the latter evaluating the philosophical density of The Game of Death (Little, 2001). In an effort to build on these isolated appraisals of Lee’s stylistic and thematic acumen, this analysis of The Way of the Dragon will be concerned primarily with Lee’s careful construction of a thematically consistent and fecund visual scheme, and not just for his fight sequences. While the colonization of Lee by the cultural studies institution has led to the routinization of analysis in the form of supratextual deconstruction, so, too, has the film studies community established an analytic routine for appraisals of martial arts films: It is standard practice in analyses of martial arts films to focus entirely on fight scenes, with the rest of the narrative being ignored or, at best, marginalized. [5] In Lee’s case, such neglect/marginalization of the non-combat scenes in The Way of the Dragon can result (indeed, has resulted) in the totality of his filmic artistry being insufficiently recognized/appreciated. As it will be argued here, Lee represents the continuation from King Hu to Chang Cheh of martial arts filmmakers treating the camera not merely as a utilitarian necessity in the documenting of extravagant martial arts, but as an artistic tool used equally for dramatic and combat purposes.

As covered in Part I, as a result of the incredible box-office success of his prior two starring vehicles, Lee was able, in 1972, to form his own production company with Raymond Chow and begin to make his own films. His first film was The Way of the Dragon, a contemporary gangster film that afforded him the ability to both practice the craft of filmmaking and, in true starteur fashion, “reshape and break the mold” (Knapp, 1996: 2) that he had established in his previous films. The plot concerns Tang Lung (Bruce Lee), who has traveled to Rome from his home in Hong Kong in order to help a family friend, Chen Ching Hua (Nora Miao), who is being pressured by local crooks to sell her restaurant. At first, Tang’s country bumpkin ways make Chen and the other employees at the restaurant wonder what help he could possibly offer; through the supreme cultivation of his martial arts prowess, however, Tang proves his efficiency in short order, almost singlehandedly toppling the small criminal enterprise that had been threatening his friend, embracing and mastering his newfound role as the “superiorly built stranger-hero abroad” (Saunders, 2009: 126).

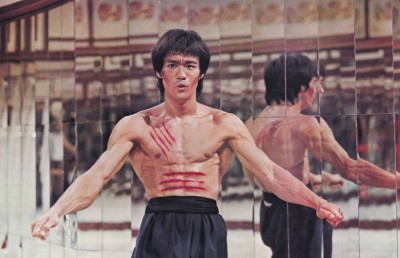

Lee’s muscular body as the site of masculine potency and nationalistic strength/pride

Of course, the fact that Lee is Chinese and muscular has led innumerable scholars to devote a disproportionate amount of time to discussing his nationality and masculinity, while others have been turned off by what they take to be (ostensibly antinomic currents of) either overt racism on Lee’s part towards non-Chinese in the hyperbolic pedestaling of his own country or a promulgation of stereotypical representations of Chinese meekness/buffoonery. [6] Not surprisingly missing from these interpretations, considering the lasting disfavor with auteurism, are Lee’s own intentions as the presiding author. “Reading into” the films’ race/gender politics in search of novel interpretations may make for fun exercise in cultural studies circles, but in striving for a historical poetics of Lee’s martial arts cinema, the starting point for the film scholar needs to be Lee and his filmmaking technique. Thus, the following analysis will offer a “close reading” of the film that seeks to elucidate the themes explored by Lee and the cinematic techniques he employed to reinforce his various thematic concerns.

Beginning literally with the very first shot (a close-up of a visibly uncomfortable Tang), which starts off a scene played for comedy with Tang being the object of a perplexed white woman’s curious stare, Lee intentionally positions himself as the “to-be-looked-at” object, to employ the famous phrase from Laura Mulvey. Recalling Knapp’s conceptualization of the starteur, Lee, armed with a keen sense of his position as a film star, is here able, as a filmmaker, to offer a conscious, comedic commentary on his position as a sexualized and fetishized other. While some of the interpretive work with Lee’s films has tried to “place” the ostensibly powerless Lee in the position of the other who is apprehensively scrutinized by the “higher” races, here it is plainly evident that Lee recognized this “subject position” and was using this Western perception as a key ingredient for this particular narrative/characterization. More than once in the hour and a half that follows this brief introduction scene, Lee will have Tang stared at by bewitched characters, both “foreigners” (the woman in the airport in the beginning of the film, the prostitute he meets shortly after his arrival, the gangsters) and even other Chinese characters (Chen, the other restaurant employees, and the homosexual character played by Wei Ping-Ao). A direct result of Lee’s transnational “outsider” experiences, Tang’s characterization “highlights the problem of cultural dislocation” and invites the spectator to sympathize with a character forced to live “in a space of anxiety, ambiguity, and contradiction” (Shu, 2003: 52-53) where they are judged even by members of their own race/culture. And speaking even more to Lee’s directorial sensibility, his superb skill at inculcating an abundance of thematic information in his mise-en-scène allows the spectator to share the sense of discomfort and anxiety felt by Tang.

Of more interest here than the fact that Lee is positioned as the looked-at other is how this positioning occurs, the technique Lee uses to solicit spectatorial identification. In the opening scene, it is significant that the shots of Tang are never from a subjective point-of-view, i.e., from the point-of-view of the woman staring at him. As opposed to aligning the camera/spectator with the woman looking, Lee positions the spectator outside of the looking/looked at dyad so as to highlight Tang’s experience of being looked at. By starting with a close-up of Tang, Lee cues the spectator, in later two-shots or long shots where Tang is not the only one in the frame, to focus on Tang and his reactions (something for which Lee would also use his character’s anomalous costuming), and with this precedent set, Lee can subsequently experiment with more complex blocking and depth-of-field, confident that the spectator will understand the nature of the mise-en-scène as expressive of Tang’s perspective.

Following this opening scene, Lee shoots a very similar scene wherein Tang is again made uncomfortable by his foreign surroundings, only in this second sequence, Lee uses greater depth-of-field and more complex framing. After he is picked up at the airport by Chen and given the rundown on the present problem with the gangsters, Chen takes Tang back to her apartment so he can drop off his things and get situated. Used to living in the “New Territories” in the Hong Kong countryside, Tang is discernibly uneasy upon entering Chen’s swanky apartment.

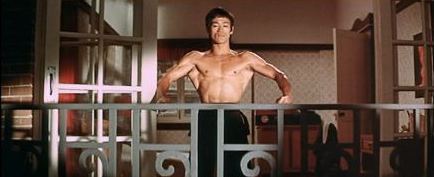

The anachronistic Tang uncomfortably seated in a posh apartment

Lou Gaul rightly observes an interior/exterior dialectic as one of Lee’s primary thematic concerns in this film, a concern that proliferates in this scene as Tang, the “fighting animal” whose “primitive fighting prowess” necessitates a “wild, open area where his spirit can soar” (Gaul, 1997: 100-101), is confined to a bizarre and disconcerting interior space. As is evident in the above screenshot, Lee frames himself in great depth so as to make himself seem small and vulnerable, and he positions the two angled chairs in such a way as to make it appear that Tang is literally trapped in this environment. Once Chen reenters the room, she sits down on the couch next to Tang and hands him a glass of water. She then immediately begins to talk, but due to the framing of the scene, with Tang in the foreground, the fact that he is not in critical focus and is receiving less light is of no consequence, for, as mentioned vis-à-vis the precedent set in the opening scene, any shot that includes Tang will be structured so as to make the spectator focus on him.

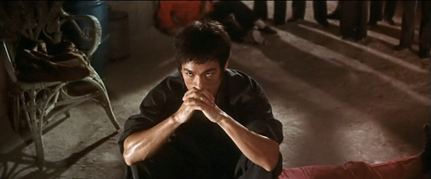

The awkward and intestinally-challenged Tang dominates the frame

The purpose of the framing is to again play up Tang’s awkwardness for comedy. After his ill-fated attempt to get something to eat at the airport [7], Tang has been plagued by an upset stomach, and now, in the middle of a conversation with Chen, he has to try to find a way to extricate himself and use the bathroom. Too modest to interrupt, though, Tang simply sits in the exact position seen in the above screenshot, never taking a sip from his glass, just waiting for her to either stop talking or say something that will allow him to interject. When he finally gets the opportunity (after she tells him not to be shy about asking her if he needs something), he quickly rushes out of the frame, leaving Chen to shake her head in exasperation.

Upon returning from the bathroom, Chen forces Tang to take a trip to the bank to secure his money. After a vexatious encounter with an overfriendly banker, Chen takes the hopelessly boorish Tang to the Piazza Navona and lectures him on proper etiquette amongst the locals. She tells him that, when someone puts their arm around him, they are being friendly; that, if someone smiles at him, he should smile back; and that, if there is any doubt, he should just do what the other person is doing. In classic screwball fashion, all during Chen’s lecture, an Italian woman (Malisa Longo) sitting nearby is making eyes at Tang, who is afforded the opportunity to commit yet another faux pas.

A prostitute captures Tang’s attention and gets him in trouble

Adroitly controlling frame space, editing, and sound, Lee cuts an accidental, nonverbal solicitation from Tang to a prostitute concurrent with Chen’s admonition of Tang’s boorish behavior. Off-screen dialogue anchors the humor, while Lee, with Keatonesque stoicism and obliviousness, is cut alternately smiling and winking at Malisa in accordance with the instructions being given him by Chen in proper interpersonal interaction, a comedic sequence reminiscent of Cary Grant unwittingly providing Raymond Massey with instructions on how to incapacitate him in Arsenic and Old Lace.

Tracking Chen down to her restaurant after his solecism with the prostitute, Tang is given more opportunities to make obvious his anachronistic presence (while Lee is given more opportunities to show off his cinematographic ingenuity). After meeting the restaurant staff, including the chef, Uncle Wang (Huang Chung-Hsin), Tang is forced once more to rush to the bathroom. Predisposed, Tang is not present when the gangsters arrive to scare off the lunch crowd and once again threaten the staff. When he emerges from the bathroom and bumps into Ho (Wei-Ping Ao), the crime boss’ second-in-command, he has no idea that Ho is “the enemy” and just thinks he happens to be a nice, regular customer with whom he engages in innocuous pleasantries. Sensing the anger in the restaurant staff and once more being admonished by Chen for improper behavior, Tang pouts angrily. He has ostensibly acquiesced to his outsider status, which Lee reinforces with the blocking and cinematography in the next scene.

After cutting to an exterior shot of the restaurant to show that it is now night, Lee cuts to a medium close-up of Tang sitting by himself and pouting at a corner table in the restaurant, from which he pans to a long shot of all of the other employees sitting together in the middle of the restaurant. Then, when a group of the gangsters returns to cause more trouble, the framing shows two distinct groupings, with the gangsters forming one group and the restaurant staff forming the other, Tang noticeably outside of both groups, seated by himself in the same isolated corner of the restaurant.

Tang having acquiesced to his outsider status

Jimmy (Unicorn Chan), one of the restaurant employees, asks the thugs to “step outside,” which initiates the first fight sequence of the film. At first, Lee’s framing propagates Tang’s outsider position, in spite of the realm of combat being a place wherein Tang might finally be able to show some usefulness. With the restaurant staff facing off against the gangsters in the restaurant back alley, Tang is still noticeably at the farthest remove from the camera, isolated at the back right edge of the frame, obviously with much to prove if he wants to be accepted in this environment.

Tang obscured and nearly pushed out of the mise-en-scène

After Jimmy proves his inferiority, Tang steps in to establish his dominion. Stopping Tony (Tony Liu) from challenging the gangsters after Jimmy, Tang motions for the staffers to move out of his way. Literally forcing himself from the outside edge of the frame to center stage, Tang finally ceases to be intimidated by his environment, asserting his self-confidence and proceeding to dispatch the four overmatched thugs with ease. After his awesome fighting display, he is jubilantly embraced by the previously contemptuous restaurant staff, finally achieving a social victory.

Whereas Gaul’s previously noted observation regarding the centrality of an interior/exterior dialectic occupying Lee’s mise-en-scène is indisputable, what he misses is the resolution of this conflict as a result of this fight scene. With the success of the first fight scene, Tang ceases to be inhibited by his surroundings. No longer the ignorant outsider, Tang has grown to where he is “neither brutish nor civilized,” but a delicate balance between the two, a “conquistador […] adapted to the fabric and equilibrium” (Saunders, 2009: 55) of his new world, confident in his ability to meet and conquer any subsequent physical or social challenge. In the next several scenes, Tang is significantly never relegated to the boundaries of the frame nor is he pushed back to its deepest region; instead, Tang frequently occupies the center of the frame space, with characters eagerly hovering around him or pushing him into the foreground.

An illustrative scene with thus far unappreciated significance to Lee’s particular characterization of Tang finds him at the breakfast table after a morning workout. Eating with no shirt on obviously does not call to mind “civilized” behavior, but more importantly, Tang comes dangerously close to offending Chen by saying he prefers the food in Hong Kong to hers, but he is able to gracefully regain his social footing and preserve Chen’s feelings. So while he is clearly no James Bond, a suave man-of-the-world with an abundance of grace and charm, he is at least making progress from being a hopeless dolt.

Tang making social progress

Having proven in the previous fight scene that he is “bodily suited to a guiding, mythological task” (Saunders, 2009: 133), Tang now occupies the position of the hero. Putting himself (literally, as will be seen in a future sequence) in the line of fire, Tang is also now the syndicate’s primary target. After once more thwarting their strong-arm tactics (in the famed double nunchaku fight scene where Tang decimates nearly the entire gang in the restaurant back alley armed only with his iconic primitive weaponry), the crime boss, tired of Tang’s ubiquity, issues an ultimatum to the restaurant staff that orders Tang delivered to him by midnight. In the case of noncompliance, Tang will be killed. Undoubtedly the sequence offering the most skillful display of cinematography, editing, and sound, it begins with the staff discussing among themselves the pros and cons of complying with the ultimatum and turning over Tang.

Motivating the low-key lighting with the lone wall light visible in the master shot, the tighter shots take on a high degree of ominousness, particularly those of Uncle Wang, whose relentless pragmatism and constant warnings of danger are beginning to take on a sinister quality.

Evincing the mythological archetype of the shapeshifter, the “wily” character who “never discloses […] the whole content of his wisdom” (Campbell, [1949] 1968: 381), Uncle Wang is appropriately lit in a fashion that signifies the dual nature of his ultimately back-stabbing character. It will be discovered at the end of the film that Wang was playing both sides after being corrupted by greed; in a foreshadowing effect, Wang is thus split here between having one side of his face lit normally while the other side catches the malevolently green flickering light emanating from the glass candle holder on the table. Convincing Chen that sending Tang back to Hong Kong is the safest move, Lee then cuts from this menacing restaurant scene to an equally foreboding scene set in Chen’s apartment. Sticking with the same noirish lighting scheme, Lee opens the scene with a shot of the clock that will propel the suspense reminiscent of High Noon. After the initial close-up of the clock, Lee zooms out to encompass Chen’s entrance into the frame. Her first action is to cast a desperate look at the clock, which reads 11:55 PM, meaning she has five minutes to get Tang to safety. Tang, meanwhile, is sitting on the couch, his feet resting on the coffee table, completely aloof and at peace as he talks of the coming Chinese New Year, the contrast in their respective demeanors heightening the tension.

Lee then cuts to a shot of a hit man taking a rifle from out of its case and looking through the scope, adjusting the focus to better survey the open window into Chen’s apartment. With the classic Hitchcockian “bomb under the table” sufficiently registered, Lee cuts back inside the apartment with a low-angle long shot of Tang on the couch, Chen’s legs entering the camera’s field of vision as she nervously paces through the shot. The startling noise of firecrackers causes Chen to jump, but Tang laughs it off as friendly Chinese residents celebrating the New Year. The sound of the clock’s relentless ticking invades Chen’s consciousness; she casts another nervous glance at the clock and sees it is now 11:57. She sits down and tells Tang that he has to leave, at which point Joseph Koo’s score initiates a persistent ringing sound, which will increase in audibility over the course of Chen’s dialogue. The ticking overlays the ringing, creating a layered soundtrack that contributes to the visuals to heighten the suspense until Lee cuts back to the sniper, at which point Koo’s percussion punctuates the danger of his presence as he zeroes in his scope on Tang.

Back inside the apartment, Lee shoots a close-up of the clock’s pendulum before rapidly raising the camera to the clock’s face, which indicates it is now midnight. The clock starts ringing and Chen starts pulling at Tang’s arm, failing to impress upon him the seriousness of the situation and now simply trying to forcibly remove him from the apartment. More firecrackers are heard, prompting Tang to suggest closing the window to block out the noise for the sake of the visibly agitated Chen. Just as he reaches his hand up to grab the shudder, however, a shot rings out and a bullet shatters the bottom of the window frame. Tang pulls Chen down out of visibility from the window and tells her to wait in the apartment as he runs out to confront the sniper.

Due to the obvious fact that there is no ideological salience whatsoever in this extended suspense sequence, it is not surprising that it has never once been discussed in extant analyses of the film. But as the work done in the prolific field of Hitchcock Studies has amply demonstrated, a lack of ideological salience does not imply a lack of artistic salience, and scholars operating under such a misguided notion can be/have been blinded to the high level of technical craftsmanship that comes from a harmonious linkage between cinematography, editing, and sound, a level of craftsmanship remarkably possessed by first-time director Lee, granting him the ability to imbue his film with a wealth of thematic interest and affective power. As more and more supratextual film analysis enters the academic discourse, it becomes clearer and clearer the “lack of an analysis of film as aesthetically charged, or functioning affectively on the spectator” (Isaacs, 2008: 3). There has been, especially in Bruce Lee Studies, a “rush into interpretation before the aesthetic has been […] clearly apprehended,” which has resulted in “an all too easy dismissal” of much of what constitutes the filmic object “on grounds that it is facile” (Darley, 2000: 6), again recalling the Hegelian trap of familiarity and the Bordwellian warning against “ransacking” film style.

One can also see in the non-combat scenes analyzed thus far the extent to which Lee went, in the move from auteur to starteur, to create a real and relatable character to play. In the tradition of Eisenstein and the nouvelle vague, Lee was as much a theorist as he was an artist, and the time and intensity he devoted to cultivating his skill in the martial arts was matched only by the time and intensity he devoted to his film art. Believing that “the aim of art is to project an inner vision into the world, to state in aesthetic creation the deepest psychic and personal experiences of a human being” (Lee, 1975: 9), and that acting is the “psychic unfolding of the personality” (Lee, 1975: 10), the impetus to his careful mise-en-scène and authentic performance becomes clear. Lee sought to create, in the construction of the film’s visual space, a window into the mind and soul of his character, and through his acting, sought to bring to life what he called the “autonomous individual,” a character who is “on his own, striving to realize himself and prove his worth” (Lee, 1975: 206), an undeniably autobiographical but at the same time universal character type. The autonomous individual, in Lee’s conceptualization, is “stable only so long as he is possessed of self-esteem,” the acquirement and maintenance of which “is a continuous task which taxes all of the individual’s power and inner resources” (Lee, 1975: 206). Tang Lung’s mythological task is thus, in line with the archetypal “hero’s journey,” the mastery of oneself; he must walk “the path of self-realization,” fittingly the most difficult road to travel, in the esoteric “cultivation of the spirit” (Lee, 1975: 206).

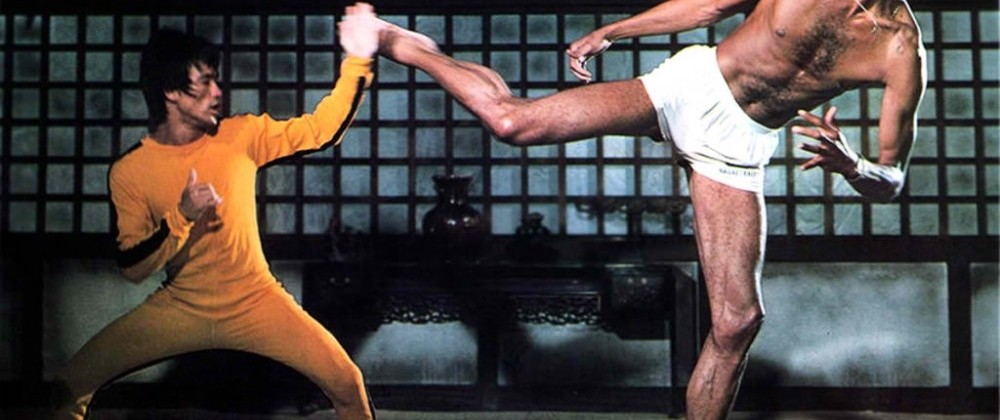

While the non-combat scenes in The Way of the Dragon are integral to an understanding of Lee’s characterization of Tang Lung and the visual representation of his thematic preoccupations, the fight scenes are undeniably important, as well. It is through physical action that Tang is able to prove his worth, both to himself and to those around him, and finally save Chen and take down the gangsters. In the spirit of the Western, The Way of the Dragon serves as a parable of physical action becoming law (Thomson, 2004: 235). Thus, the deservedly famous showdown between Tang and Colt (Chuck Norris), the American martial artist hired by the syndicate to finally get rid of Tang, can be viewed as constitutionally sacrosanct combat wherein the victorious martial artist’s supremacy constitutes legal dominion in the matter at hand. The interested parties—the restaurant staff, on the one hand, and the crime syndicate, on the other—each have their legal counsel, only instead of arguing legalities in a court of law, Tang and Colt will engage in mortal combat on the hallowed ground of the Roman Colosseum, and to the victor belong the spoils.

To understand the meticulousness with which Lee visually structured the Colosseum fight scene, a return is necessary to the previous two fight scenes that took place in the restaurant back alley. While discussing the first fight scene, Gaul off-handedly comments on the peculiarity of a particular shot where Lee is seated and looking up at two approaching thugs, whose point-of-view Lee’s camera has briefly occupied.

After pointing out the existence of this shot, Gaul goes no further in theorizing its significance. Based on the earlier instances of characters looking at Tang and making judgments based on his appearance/behavior, it becomes explicit in this particular shot Lee’s subversive efforts in inverting the position of power from one looking down to one looking up. Based on his race, culture, class, etc., Tang/Lee may occupy a particular sociological/ideological position in the minds of others, but that position is less a prison and more a starting block and to attempt to keep Tang/Lee imprisoned in such a constraining sociological/ideological position is to risk being taken by surprise by the strength within him. Spending his life being alternately ignored, underestimated, or ridiculed, Lee takes the opportunity, as Tang, to poke fun at and ultimately rise above this discursive position. The fact that he “stooped to play the fool” highlights not a propagation of weakness/inferiority, as suggested by Teo’s disfavor with Lee’s characterization; more strikingly, it highlights Lee’s “superiority and satirical might as a representative” (Saunders, 2009: 119) of the strong transnational outsider. Within the film, he “unmasks, ‘sees through’, the fiction upon which the social link of the existing power structure is founded” (Žižek, 2005: 229), and the fact that Lee shoots the point-of-view dolly shot with very slow movement signifies the apprehension with which the thugs are approaching this shockingly competent individual. Their other two friends paid for their ignorant denunciation of the Chinese country bumpkin with their consciousness, and even though Tang is seated in a position of ostensible weakness and inferiority, they have seen what lies behind the façade and are now approaching with respectful caution.

Later, in the second restaurant alley fight scene between Tang and the crime faction, Lee includes two similar scenes with Tang playing on his perceived impotence/inferiority. First, when being led out to the alley at gunpoint, Tang is walking with his hands up. Eventually, the thug with the gun tells him he can put his hands down, but Tang blankly stares at him as if he does not understand. He keeps up the ignorance charade long enough for the thug to let his guard down, put at ease by Tang’s apparent fatuity, at which point Tang quickly strikes him in the groin and removes the gun from his possession.

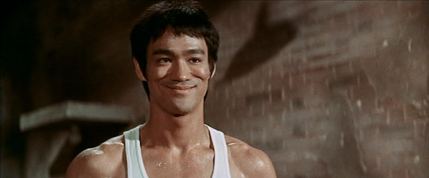

Lastly, during the same fight scene, Tang, approached by one of the knife-wielding gangsters after having already displayed an abundance of combative efficaciousness, flashes him “an obtuse-looking but deceptively passive smile” (Saunders, 2009: 128) before unleashing a vicious torrent of strikes with his nunchaku, a signification to the gang that he has officially invalidated the currency in their perception of him as an unthreatening idiot.

Tang/Lee acknowledging, subverting, and mastering others’ ignorant perceptions

Clearly, Lee had an astute understanding not only of the power of satire and general good humor in the structuring of his narrative and the remolding of his persona through the character of Tang Lung, but also of the power of the camera in his strategic deployment of various identification—or, more to the point, identification manipulation—techniques. Conceding this assertion, the spectator viewing the final fight between Tang and Colt is enabled to recognize the subtle Hitchcockian shift in perspective at the crucial turning point of the fight, a move executed by Lee in order to condemn the senseless bloodlust overwhelming martial arts cinema at the time, the most brilliant and poignant achievement of his all-too-short career as a filmmaker. Much has been made in discussions of The Way of the Dragon of the classic Colosseum encounter; as possibly the most famous scene in martial arts cinema, it is not surprisingly the most frequently discussed scene in critical analyses (aesthetic, textual, and supratextual alike) of the film. Yet, because of the lack of authorial context and the indifference to form and narratology in the extant analyses, there is still much to be gleaned from further analysis.

Most popularly, especially over the last decade, scholarship on martial arts cinema promulgates an affinity with dance in the prioritization of the physical movement inherent in martial arts over any alleged supratextual ideological saliency. [8] As logically attested to by Mélanie Morrissette, “before any social and political analysis,” for which martial arts cinema “seems to fulfill some needs,” the aesthetic rendering of the physiological “should be the major subject of analysis” (Morrissette, 2002). Arguing on the same line, Aaron Anderson posits that “mimetically representational fights” seek above all else to “convey a narrative story;” thus, the “aesthetic aspect of this stylization” of combat inherent in cinematic representation must attain primacy in ascribing meaning to a particular fight scene, or as Anderson terms it, a particular “movement-narrative” (Anderson, 1998). Problematically, action scenes are often reduced in theory to pure spectacle, indulgent scenes that are alleged to “‘freeze’ the narrative in its tracks” (Anderson, 1998). Thus, the film studies institution’s codification of martial arts film analysis as purely the province of aesthetic analyses of fight scenes (the only scenes worth looking at in this condescendingly trivialized “cinema of attractions” plagued by juvenile storytelling) has inculcated the notion that the fight scenes, as spectacles, cannot possibly contain thematic currency, neither intrinsically as a “movement-narrative” nor as a thematic link in the overall narrative chain (which is itself allegedly devoid of thematic acuity).

In direct contrast to these widely held assumptions, analyzing the Colosseum fight scene in The Way of the Dragon enables one to recognize both the scene’s relevance to the rest of the film—as previously discussed, its signification of juridical combat in the settling of the restaurant dispute—as well as Lee’s investment in it as a thematically rich “movement-narrative.” The most commonly asserted meaning of this fight scene is its serving as “one of Lee’s performative ‘lessons’ ‘about’ martial arts (Bowman, 2010: 76), and indeed, this is the most explicit of its meanings as offered by Lee, the perennial pedagogue of martial arts cinema. Searching deeper, a meaning ascribed to the sequence by Leon Hunt vis-à-vis spectatorial identification, endemic of the ideology-inclined cultural studies colonization, places race/culture as the main determinant of identification and emotional impact:

Watching [martial arts] films as a white, Western fan […] may involve a degree of identification with Bruce Lee […] but it may also lead, at some point, to finding one’s counterpart in the gwailo […] I may not want to […] identify with Chuck Norris in The Way of the Dragon […] yet part of me knows that the Lee/Norris [Colosseum] fight embodies a patriotic structure of feeling that is supposed to at least partly exclude me (Hunt, 2003: 3).

Resultant from the cultural studies dogma that “films cannot possibly be thinking,” that they and their makers are helpless prisoners “in the repressive grip of ideology, a grip only theory [re: theorists] can break” (Rothman, 1999: 35), Hunt falls into the same reductive trap that removes film from the realm of art and the filmmaker from the realm of artist. More beneficial, especially in turning to martial arts cinema, is to work from an aesthetic/textual viewpoint that enables one to register, analyze, and appreciate the films’ richness and complexity. For the Colosseum scene in particular, as already asserted, Lee’s continued utilization of identification manipulation techniques provides the greatest salience in the breakdown of how Lee triggers within the spectator the “multiplicity of affects available for stimulation” (Carroll, 2008: 148) beyond the restrictive domain of ideological deconstruction.

For Hunt, the notion of “identification” is unproblematic and straightforward, and indeed, this essay has also made use of the term as a signifier of the vague psychological connections often made between spectators and characters. For Noël Carroll, the concept of identification represents one of the most frustratingly malleable terms in all of film studies, to which he has devoted a considerable amount of time and energy interrogating. More productive than using the term “identification” as a catch-all for the “diversity of phenomena” experienced by filmgoers, Carroll prefers discussing the affective system of the spectator, affect being defined as a broad compass comprised of “hard-wired reflex reactions, like the startle response, sensations (including pleasure, pain, and sexual arousal), phobias, desires, various occurrent, feeling-toned mental states—such as fear, anger, and jealous—and moods” (Carroll, 2008: 149). It is also important to note that the specific affective realm with which Lee is concerned in the Colosseum scene is the emotional realm, in which “differential computational appraisals of stimuli” cause the spectator to experience “visceral feelings” (Carroll, 2008: 151). Lee seeks to take the spectator beyond a sense of detached voyeurism and truly bring the spectator into the fight, to viscerally experience it alternately from the two opposing combatants’ perspectives.

Standard martial arts film practice of the era typically saw the protagonist face his/her enemy (who, by the finale, had been sufficiently demonized in what was often a one-dimensional characterization/caricature) with murderous intent, relishing the opportunity to inflict bodily damage and unhesitatingly dealing the fatal blow (e.g. Come Drink with Me, The One-Armed Swordsman, Five Fingers of Death). The predominance of the revenge trope in this genre can be seen as the most convenient way of alleviating any moral/ethical concerns for the spectator, who can comfortably enjoy in watching, if not in some sense participating in, the violent and bloody carnage offered up for their entertainment. And Lee was the first person to acknowledge that the films he made for Wei made use of this trope. Even though he had twice played avenging angels who, by film’s end, had racked up a considerable body count, he always insisted by way of mitigation that his characters be punished, first with arrest in The Big Boss and then with death in Fist of Fury. [9] In The Way of the Dragon, Lee would take the opportunity as the presiding author to give his philosophy of cinematic morality more explicit treatment than ever before.

In the early stages of the fight, Colt is getting the better of Tang. Forced to adapt his fighting style to the larger and stronger opponent, a substantial portion of the middle section of the fight sees Tang turning the tables on Colt. Arguably the most exceptional display of fight choreography and general martial artistry in Lee’s entire oeuvre, the portion where Tang frustrates Colt with the diversity of his offense and his Ali-inspired perpetual motion is some of the easiest martial arts cinema in which the spectator can vicariously participate through Lee’s supremely cultivated hero. Inserts of a cat help to invoke a sense of playfulness, of the clearly superior Tang toying with the perplexed Colt in the same fashion as the cat is seen pawing a loose rock on the Colosseum floor. This untroubled sense of enjoyment in watching Tang mercilessly punch and kick another human being is devoid of all of its physical and emotional gravitas, and while this is no doubt to satisfy the prerequisite of the genre to provide interest in martial spectacle, a more discerning appraisal can uncover a supreme cinematic dexterity whereby Lee leads the spectator down this path of simplistic entertainment only to blindside them with a lurch in tone that reveals Lee’s true and profound intention.

In the existing scholarship on Vertigo, scholars are in almost unanimous agreement that the flashback where Hitchcock takes the viewer from out of Scottie’s (James Stewart) consciousness and into Judy’s (Kim Novak) “constitutes nothing less than the decisive turning point” (Keane, 2009: 237) in the narrative, the effect of which “is ruthlessly to expose” (Wood, 1989: 363) the nature of Scottie’s actions, ranking “among the most disturbing and painful experiences” (Wood, 1989: 387) in all of Hitchcock’s cinema in the way it makes it wholly impossible to resume an unproblematic psychological and emotional alignment with Scottie as the film approaches its conclusion. At the risk of continuing to compare a first-time director to one of the masters of the art form, Lee’s efforts in staging the fight between Tang and Colt are identical to those displayed by Hitchcock in Vertigo, and achieved through identical means. Having just invested so much emotionally in rooting for Tang, cheering with a bloodthirstiness for more violence after each landed strike, Lee now forces the spectator to both confront the sight of a man suffering in agonizing pain from the onslaught of violence just administered, and even share his pain.

At this crucial point in the fight, Tang has established his superiority, repeatedly stifling Colt’s offense while landing his own strikes at will. Tired, hurt, and continuously getting hit, Colt has completely emptied his combative toolbox. He has nothing left to throw at Tang, who is still irritatingly bouncing around, his perpetual motion creating, defensively, an impossible target to hit, while offensively, he is intolerably unpredictable. In borderline cruel fashion, Lee indulges in a technique of misdirection whereby, in identical fashion to when Tang, after originally appearing overmatched, changed up his technique and gained the competitive edge, Colt now begins mimicking Tang’s movements, bouncing around and throwing sidekicks, evidently now on an even playing field with Tang. The music even picks up the exact same triumphant cue as heard before, only Lee allows Colt a mere glimpse of promise, snuffing out the music and extinguishing Colt’s last desperate attempt to achieve the success he was enjoying in the initial stages of the fight with a ferocious series of punches that floors Colt. It is at this precise moment that Lee executes his filmic coup, inserting a subjective shot from Colt’s punch-drunk point-of-view of a blurry Tang, at the same time cueing a dour and foreboding note on the soundtrack. The dynamic of the entire fight scene shifts in this instant from one of vicarious thrill to one of morbid disavowal. No longer a bloodthirsty Roman peasant witnessing a gladiatorial slaying for general amusement, Lee forces the spectator to focus not on the victor, but the loser, to impress the important point that mortal combat is not some abstract, metaphysical concept existing in antiquity to be used frivolously for entertainment purposes, but a real condition of life, past and present, that involves pain and suffering, and that, if used in the cinema, must be used in a humanistic manner, a commonplace notion in the genre now (e.g. Best of the Best and Lionheart) but unheard of at the time as to its radicality.

After the dynamic of the fight has shifted, what follows is Colt’s continued subjection to Tang’s superiority. His painful sluggishness is now no match for Tang’s lithe speed. An attempted roundhouse kick from Colt merely allows Tang the opportunity to use his speed to kick Colt’s back leg out from under him, sending him crashing to the concrete once more. And, rather than cutting to a shot of Tang, Lee keeps the camera focused on Colt, who remains on his back, groaning in pain. In offering a theory of “kinesthetic response,” Anderson talks of how the spectator witnessing physical movements onscreen can experience “muscular sympathy,” a process whereby the spectator is not only imagining, for example, how cool it would be to be able to move and kick like Bruce Lee, but whereby, calling to mind past experiences of either hitting someone or being hit, the spectator calls on a physical rather than a psychological response to that which is on film. Painful and injurious experiences in human experience thus allow the spectator witnessing Colt’s progressive dismantling to muscularly sympathize with his physical pain. As Anderson asserts, “the body itself, through empathic physical sensation, participates” in the “viewed movement” (Anderson, 1998).

By the end of the sequence, at which point Tang has beaten Colt to the brink of blindness, thoroughly bruised and bloodied his face, and even broken one of his arms and one of his legs, Lee finally returns the spectator to Tang’s point-of-view. The extended and excruciating excursion into Colt’s subjectivity allows for Tang’s eventual veneration of Colt to be shared by the spectator. Without using dialogue, Lee cuts a series of looks between Tang and Colt wherein Tang is pleading with Colt to concede defeat. Adhering to the warrior code, Colt chooses “death before dishonor.” With one good arm and on one good leg, Colt lunges at Tang, who reluctantly kills Colt, settling the matters of the “movement-narrative” and the overall narrative once and for all but achieving something much more impressive and profound than merely providing an exciting climax. While the fight between Tang and Colt unavoidably invokes a sense of cultural jingoism, with the minority trouncing the hubristic imperialist, Lee had the sagacity to demarcate the racial/cultural line so as to make his erasure of that line all the more conspicuous and poignant. If it is an ideological message one is determined to find in the work of Bruce Lee, then the search can end with this sequence’s tragically beautiful coda featuring Tang paying tribute to his felled brother by symbolically laying him to rest with his belt and dobok.

Lee’s final proclamation, achieved through purely visual means, persuasively contends that “if we are to overcome the ‘effective’ social power, we have first to break its fantasmatic hold upon us” (Žižek, 2005: 231). Lee was determined—as a man, husband, father, martial artist, and filmmaker—to move beyond race, culture, ideology, religion, class, gender, occupation, education, style of martial arts, etc., in an effort to find that transcendental autonomous individual. If it is at all possible to sum up the essence of a human being in a single statement, the closest to success one could come in attempting to sum up Bruce Lee would be to recall his answer to Pierre Berton’s question of whether he considered himself Chinese or American: “I want to think of myself as a human being,” because “under the sky” there is “but one family: It just so happens that people are different” (Lee, 1971).

Just as Lee did not pretend to dismiss culture, race, and ideology as insignificant, this essay’s efforts have not been to remove ideological critique from relevance in the analysis of cinema. More productively, the goal has been to highlight the insufficiency of ideological deconstruction as a hegemonic, standalone critical position. As Bruce Lee proclaimed, “there is no such thing as an effective segment of a totality” (qtd. in Little, 2001: 91). The essence of cinema is its lack of a single fixed and tangible essence; it thrives based on its magnificently irreducible multidimensionality. Far more than just the mechanistic offspring of the cultural machine in need only of ideological deconstruction, the great artworks in cinema are “fed by a complex generic tradition and, beyond that, by the fears and aspirations of a whole culture,” at once transcending their individual makers while at the same time being inconceivable without them (Wood, 1989: 296). And such is the case with the martial arts cinema of Bruce Lee.

Endnotes

1 First, a full-length critical overview from film critic Lou Gaul (1997), and second, an anthology of Lee criticism edited by Jack Hunter (2005), which presents a short essay for each of Lee’s four completed films plus an essay on the 1978 version of The Game of Death, which brings up an important point to be made regarding this particular film’s legacy. For three decades, fans and scholars interested in Lee’s incomplete final film, The Game of Death, had no material with which to work other than the infamous 1978 film released by Columbia Pictures. That film included only half of the footage Lee shot before his death (all that was recovered at the time) and not a single remnant of Lee’s original story (neither Robert Clouse, who directed the non-Lee footage from the 1978 version, and Columbia nor Raymond Chow and Golden Harvest were able to recover Lee’s original story outline), creating a myth akin to Stroheim’s Greed about the lost, “real” version. It was not until the 2000 documentary Bruce Lee: A Warrior’s Journey that the world was able to see all of the existing footage shot by Lee and edited (by John Little) according to his specifications. Little also released a companion book in 2001, which contains Lee’s recovered original treatment for The Game of Death as well as the only existing textual analysis of this particular version of the film (the analysis offered in Bowman’s text, aside from being grossly specious, is far too brief to be considered alongside Little’s rigorous interrogation, although he does at least direct his attention to the film Lee intended). Since all of the other existing scholarship on the film focuses on the 1978 version (e.g. in Gaul’s text and the Hunter anthology), which is a severe violation of Lee’s original artistic vision, it is of course the Little book that should be consulted by readers interested in the continued, albeit aborted, evolution of Lee’s filmmaking from The Way of the Dragon to The Game of Death.

2 As Hegel posits, “the commonest way we deceive either ourselves or others about understanding is by assuming something as familiar and accepting it on that account” (Hegel, [1807] 1998: 18). Adding to the irony, it is Bowman himself who sagaciously observed this danger (Bowman, 2010: 45) in Bruce Lee Studies, yet, similar to the “Kantian Parallax” elucidated by Slavoj Žižek, Bowman, restricted as he was by his cultural studies framework, was able to recognize but not escape the danger presented by the Hegelian trap of familiarity (Žižek, 2006: 25).

3 For example, Peter Rist, writing for Offscreen about a special series of screenings of Hong Kong martial arts movies hosted by the UCLA Film & Television Archive in 2003, acceded that it was understandable that Lee’s films, as popular as they are, would be ignored (Rist, 2003).

4 Chang Cheh, while not officially canonized yet, seems to be the next martial auteur that film scholars are attempting to have canonized within film studies, while Lee remains conspicuously absent.

5 In Making Meaning, Bordwell discusses what he terms “nodal passages” (Bordwell, 1989: 214), the scenes that, having subordinated the film to his/her established argument, the interpreter surgically removes to support his/her position. Obviously, the inherent weakness in this methodology is that it is “partial and one-sided” with the interpreter essentially “concealing those parts of the film that don’t fit” (Bordwell, 1989: 214) the already formulated argument. In general terms, obvious nodal passages are opening scenes, climaxes, and endings. In the case of martial arts films, however, even these sequences tend to be ignored, with the fight scenes being viewed as the only areas worth studying. See, for example, Bordwell’s analysis of King Hu, wherein he makes the claim that “naturally, the most inviting objects of stylistic inquiry are […] fight scenes” (Bordwell, 2000: 113). He does acknowledge that “dramatic and expository scenes” in martial arts films “are not without stylistic interest” (Bordwell, 2000: 113), but because the fight scenes are so attractive to the scholar and because they are what readers expect to be analyzed, the rest of the films are inescapably ignored and the totality of the various artistic visions cannot possibly be adequately assessed/appreciated. Thus, the goal here in analyzing The Way of the Dragon is to not elevate one over/at the expense of the other, but to show how they both come together in the structuring of a single, thematically unified narrative.

6 Much was already made of Lee vis-à-vis nationality and masculinity in Part I of this essay. To the charges of racism on Lee’s part towards non-Chinese, see Peggy Chiao, who identifies Lee’s “blatant racism” as “one of the major weaknesses of his films” (Chiao, 1981: 38). As to the disfavor regarding his “bumpkin persona,” see Teo (1997: 116-117). Teo does acknowledge a potential subversive power in Lee adopting such a persona. However, he ultimately comes to disavow it as the regression of a previously “heroic figure into a parody” (Teo, 1997: 116). So, while Teo acknowledges the presence of potential subversive power, he argues that Lee is unable to realize it through a lack of filmmaking savvy, a conclusion likely stemming from an allegiance to Lee as a symbol of nationalistic pride. As such, it is logical, if unhelpful, that Teo was turned off by Lee’s “indulgence in playing the bumpkin” (Teo, 1997: 116) over the ascension of Chinese strength. For a more tempered appraisal of this film and Lee’s characterization therein, see Teo’s subsequent discussion of Lee in his charting of the historical evolution of Chinese martial arts cinema (Teo, 2009: 74-81).

7 In a sequence cut from many of the international releases of the film but restored for a number of the more recent DVD releases, Tang enters the airport restaurant in the hopes of getting some food in his stomach before Chen arrives to pick him up. Unable to read the menu, Tang points to a series of items for the waitress to bring him, unaware that he just asked for every soup on the menu. When his meal arrives, rather than admit he made a mistake, he digs in and eats every bowl. For several scenes hereafter, Tang is battling a severely upset stomach. Other sequences cut from this film include an extended encounter with the Italian prostitute, who takes Tang back to her apartment after Chen runs off. Tang, oblivious to her intentions, is mortified when she emerges from her bedroom naked and runs from the apartment. Lastly, there is another bathroom joke calling back to the soup incident where Tang, while at Chen’s restaurant, uses the bathroom and is seen by a local using the toilet as if it were a squat toilet.

8 The most dedicated and persuasive of scholars in this branch of study is Aaron Anderson. In particular, his Jump Cut (1998) essay on kinesthesia in martial arts films is illustrative of the points of focus for this type of aesthetic analysis. Also in line with Anderson’s work on martial arts and dance is Mélanie Morrissette (2002), whose Offscreen essay on the importance of choreography in the creation of meaning in physical action onscreen is invaluable for the continued aesthetic analysis of martial arts cinema in film studies.

9 To read Lee’s thoughts on violence in film and his ambitions on this front as a budding filmmaker, see The Wisdom of Bruce Lee (Dennis and Hutchinson, 1976: 98-108).

Bibliography

Anderson, Aaron. “Kinesthesia in Martial Arts Films.” Jump Cut 42 (1998). Web.

Anderson, Aaron. “Asian Martial Arts Cinema, Dance, and the Cultural Languages of Gender.” Chinese Connections: Critical Perspectives on Film, Identity, and Diaspora. Ed. Kam Tan See, Peter X. Feng, and Gina Marchetti. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2009. Print.

Bordwell, David. Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1989. Print.

Bordwell, David. “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse.” The Cinema of Hong Kong. Ed. David Desser and Poshek Fu. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2000. Print.

Bowman, Paul. Theorizing Bruce Lee: Film-Fantasy-Fighting-Philosophy. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2010. Print.

Bruce Lee: A Warrior’s Journey. Dir. John Little. 2000. DVD.

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, [1949] 1968. Print.

Carroll, Nöel. The Philosophy of Motion Pictures. Malden: Blackwell, 2008. Print.

Chiao, Peggy. “Bruce Lee: His Influence on the Evolution of the Kung Fu Genre.” Journal of Popular Film and Television 9.1 (Spring 1981): 30-42. Print.

Darley, Andrew. Visual Digital Culture: Surface Play and Spectacle in New Media Genres. London: Routledge, 2000. Print.

Dennis, Felix and Roger Hutchinson. The Wisdom of Bruce Lee. New York: Pinnacle, 1976. Print.

Gaul, Lou. The Fist That Shook the World: The Cinema of Bruce Lee. Baltimore, MD: Midnight Marquee, 1997. Print.

Hegel, G.W.F. The Phenomenology of Spirit. Trans. A.V. Miller. Delhi: Shri Jainendra Press, [1807] 1998. Print.

Hunt, Leon. Kung Fu Cult Masters. London: Wallflower, 2003. Print.

Hunter, Jack, ed. Intercepting Fist: The Films of Bruce Lee. London: Glitter, 1999. Print.

Isaacs, Bruce. Toward a New Film Aesthetic. New York: Continuum, 2008. Print.

Keane, Marian E. “A Closer Look at Scopophilia: Mulvey, Hitchcock, and Vertigo.” A Hitchcock Reader. Ed. Marshall Deutelbaum and Leland Poague. Malden: Blackwell, 2009. Print.

Knapp, Laurence F. Directed by Clint Eastwood: Eighteen Films Analyzed. Jefferson, NC: McFarland &, 1996. Print.

Lee, Bruce. The Tao of Jeet Kune Do. Burbank, CA: Ohara Publications, 1975. Print.

Lee, Bruce. “Bruce Lee.” The Pierre Berton Show. 9 Dec. 1971. Television.

Little, John. Bruce Lee: A Warrior’s Journey. Chicago: Contemporary, 2001. Print.

Logan, Bey. The Way of the Dragon. Dir. Bruce Lee. Hong Kong Legends, 1972. DVD. Platinum Edition. 2006. Audio Commentary.

Morrissette, Mélanie. “Choreography: The Unknown and Ignored.” Offscreen 6.8 (2002). Web.

Rist, Peter. “UCLA’s “Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film.” Offscreen 7.6 (2003). Web.

Rothman, William. “Some Thoughts on Hitchcock’s Authorship.” Alfred Hitchcock: Centenary Essays. Ed. Richard Allen and S. Ishii-Gonzales. London: BFI, 1999. Print.

Saunders, Dave. Arnold: Schwarzenegger and the Movies. London: I. B. Tauris, 2009. Print.

Shu, Yuan. “Bruce Lee to Jackie Chan: Reading the Kung Fu Film in an American Context.” Journal of Popular Film and Television 31.2 (Summer 2003): 50-59. Print.

Teo, Stephen. Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions. London: BFI, 1997. Print.

Teo, Stephen. Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2009. Print.

Thomson, David. The Whole Equation: A History of Hollywood. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. Print.

Wood, Robin. Hitchcock’s Films Revisited. New York: Columbia UP, 1989. Print.

Žižek, Slavoj. Interrogating the Real. Ed. Rex Butler and Scott Stephens. London: Continuum, 2005. Print.

Žižek, Slavoj. The Parallax View. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2006. Print.