A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (Steven Spielberg, 2001) as Intertextual, Reflexive Monster

The opening VO tells us of a global warming that has led to the melting of polar ice caps and destroyed cities, NY, Venice, Amsterdam, and made natural resources a luxurious premium, to the point where human population must be controlled. The resulting impact on the economic and social structure is a world where robots become common ‘tools’ that replace the resource hungry human. The opening scene, with a benign God-like scientist Professor Hobby, played by William Hurt, talks to his young employee base of his company, Cryogenics, about his dream: to construct a surrogate child robot, a robot that can be taught to love and be loved in turn. His dream has a two-fold function: commercial, since it could lead to huge sales in a world where the population count is down, and purely a search for power, to play God by creating a robot that can, in effect, not only love but dream (in this respect Hobby is a surrogate for Spielberg, who places great emphasis on his art to be a source for realizing dreams). When an employee asks Hurt “What responsibility does a human have to a robot that genuinely loves?” Hurt replies, “In the beginning, didn’t God create Adam to love him?” The film skips ahead 20 months to a company employee Henry Swinton who has a son suspended animation awaiting the cure for his incurable illness, which makes him a prime candidate for the first “Mecha child” (mechanical as opposed to organic) off the assembly line. The young couple of Monica and Henry Swinton (Frances O’Connor and Sam Robards) are pegged to be the guinea pigs for the company prototype mecha child; Henry is quick to push the surrogate child onto Monica, who resists at first until her mother instincts take over. Once she says the seven words that will ‘imprint’ young David (Haley Joel Osmont) into being Monica’s long lost love child, the cast has been dyed. David’s first few days in play like the common ‘stranger in a strange land humor,’ but with some genuinely touching moments, like David’s wonderful introduction to both the house and the audience. Spielberg places his camera up close on David’s glossy white shoes as they step down onto the hard wood floor (perhaps an homage to 2001, and the cut to the close-up of a flight attendant’s ‘grip’ shoes). It cuts to a three-quarter shot of David, as he utters his first words, “I like your floor!” Nothing like bringing such a momentous occasion literally, down to earth. The experiment in surrogate parenting is made more difficult with the arrival of their son by birthright Martin returns home after a cure is found for his illness. Expected sibling rivalry ensues, including a pool side scene where the (innate?) cruelty of children comes to the fore, with Martin and his friends goading and insulting David. An accident caused by David leads to the near drowning death of Martin, and the father’s eventual decision that David is too dangerous and must be returned to the company, where he will be destroyed. Monica is entrusted with the task but can not go through with it and instead leaves David stranded in the woods, along with his Teddy Bear, to live as a renegade mecha. At this point the film switches gear into David’s journey of self-discovery.

A.I. (top) and 2001

There are two fascinating aspects of this film: the aesthetic tension between Kubrick, who nurtured this project for over 20 years, and Spielberg, who took over the reins (with Kubrick’s full consent) after Kubrick’s death in 1999 to write, produce and direct. The common and often stated difference between two directors as one being the cold intellectual (Kubrick) and the other an optimistic sentimentalist (Spielberg) play out in a tug of war with neither camp winning out entirely. The Kubrick half keeps the film from succumbing to a common Spielberg pratfall of resorting to excessive sentimentality. The film also straddles (and one could argue is stronger for it) the divide between Spielberg’s preferred classicism (belief in humanity, clarity of idea and resolution, transparent style) and Kubrick’s tendency toward modernism (irony, relative value, distrust in humanity, rigorous formal style). The partial elements of postmodernism seem to be split across both directors, a sense of nostalgia with Spielberg and the bitterness and sense of relative value with Kubrick. Hence while the core of the film remains pure Spielberg –the boy’s undying love for his mother to prove his ‘humanity’ and win her unrequited love– there are enough touches of irony and a sense of bittersweet to appease the Kubrick fans of the equation.

A second fascinating aspect of the film (apart from the stunning achievements of the well-oiled teamwork of the cinematography, art direction, set design and special visual effects) is the myriad of cinematic references that are invoked across the film, some directly and consciously, but a good many I would guess indirect. My sense is that much of this intertexuality is a result of the film percolating first in Kubrick’s mind and then Spielberg’s since the early 1970s, like a sponge soaking in cultural and artistic ideas that were circulating during those times, spanning the tail-end of high point of intellectually stimulating science fiction of the late 1960s, early 1970s (2001, 1968, Planet of the Apes, 1968, Solaris, 1972, Silent Running, 1971, THX 1138, 1971, Zardox, 1971, A Clockwork Orange, 1971, The Man Who Fell to Earth, 1976, to the more spectacular, special effects dependent epics of the late 1970s, early 1980s (Star Wars, 1977, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, 1977, Alien, 1979, Tron, 1982, Terminator, 1984, Brazil, 1985), to the mega-epics of the mid to late 1990s, Jurassic Park, 1995, Twelve Monkeys, 1995, Independence Day, 1996, Starship Troopers, 1997, and The Matrix, 1999.

The film is rich in thematic ideas, drawing on cinema history (mainly cinema of the fantastic), fairy tales, classical mythology, popular mythology and religion. As one scene followed another I kept a running count of the films and ideas that came to mind, and the list included:

1) Ray Enright, Busby Berkeley’s Dames, 1934. The film sources the Dick Powell sung “I Only Have Eyes for You,” an interesting choice for those who know what the song is about and the Berkeley choreography, which includes dozens of women who look identical to Powell’s love interest, Ruby Keeler). The notion of female conformity and the robotic, look-a-like mise en scene makes for an apt reference point for A.I..

2) The Adventures of Pinocchio the 1883 children’s novel by Carlo Collodi, along with the 1940 Disney animated adaptation Pinocchio, is perhaps the most evident and powerful influence on the film, given that the story is directly referenced in the film. In the classic story, woodcarver Geppetto (Professor Hobby in the film) makes a wooden boy named Pinocchio who, like the robot David, dreams of becoming a real boy. In the story, the Blue Fairy transforms Pinocchio into a real boy, but his transformation is only partially complete, as he must first go through a series of initiations and challenges to prove himself a real boy. Some of Pinocchio’s journey into truth, identity and self-hood serves as an inspiration to the film. It should also be noted that the company that designed David has a logo in the shape of a winged bird, which echoes the blue fairy.

3) Tod Browning’s Freaks, 1932, and David Lynch’s The Elephant Man (1980) are evoked namely in the scenes at the Flesh Fair: A Celebration of Life, where David, who looks more human-like than his more prosaic robot ‘worker’ models (there is more than a hint of class conflict, class exploitation here) comes into contact with the harsher, uglier aspects of human nature ( this also references Voltaire’s classic 1759 satire of the innocent exposed to the cruel world, Candide). The robots are kept in zoo-like cages, gawked at and exploited for commerce; in one of the film’s few offensive moments, a black robot is jettisoned out of a canon. The way the robots bond together against their human aggressors recalls the similar interplay between humans and ‘freaks’ in the Browning and Lynch films; also invoking The Elephant Man is the Victorian-styled bounty hunter character Lord Johnson-Johnson, played by Brendan Gleeson, who captures renegade robots and sells them to ‘show business’ for profit; the Lord recalls the Victorian era circus owner Bytes, played by Freddie Jones; and the final scene where David sleeps like a normal person for the first time, and we presume ‘dies’, recalls the ending where Merrick sleeps lying flat on his back for the first time, knowing the position will cause his death. Interestingly, Merrick’s death is followed by a fantasy dream of his mother’s face hovering in outer space. Whereas in David’s mind, lying down next to his (dead/dying) mother will lead to sleep, which he has learnt is the place where dreams are born; Merrick’s lying down to die leads to a final wish fulfillment dream of his mother materializing as a godhead.

4) The Lost City of Atlantis. There have been countless myths and tales from Plato (The Republic) onwards that recount the story of a lost underwater city (or in some cases continent). One of the most interesting (and lesser known) cinematic uses of this utopian tale is the Soviet science fiction film, ?? Amphibian Man?? (1962, Vladimir Chebotaryov, Gennadi Kazansky), where a doctor plans to build a ‘classless’ utopian underwater society. The fate of the water circled city is noted in the opening voice-over of A.I., which tells of natural catastrophes that have destroyed whole cities, citing Venice, Amsterdam and New York City. The underwater scenes where David searches for the Blue Fairy and finds her in the submerged remnants of New York City (Coney Island is noticeable) falls squarely into the tradition of this myth.

5) Tarkovsky’s Solaris is another huge influence on (or mirror of) A.I.. For starters, there is the idea of the inhuman replicant, Hari, who is more openly expressive of emotions than her human husband, scientist Kris Kelvin. The scene near the end, after the film has flash-forwarded 2000 years to a post-human world, seems to draw (directly or indirectly, perhaps through Soderbergh’s 2002 remake) from the surprise ending of Solaris, where what we believe to be Kelvin back on earth at his parental country home, is in fact a materialization of this ‘reality’ taken from his own mind on one of the planet Solaris’ many oceans. Spielberg draws from this ‘reality simulacrum’ for the entire scene where the aliens recreate David’s home, like a memory simulacrum, so that he can relive his dream of meeting his mother again. Like in Solaris, the depiction of the ‘real’ place is estranged by subtle or little differences in visual representation (for example, the colors in David’s home are saturated and garishly overdone through the cinematography).

6) Tarkovsky’s first film Ivan’s Childhood (made the same year as Amphibian Man, 1962) also features a young boy who is a perpetual ‘dreamer’ as the central protagonist. The ending of A.I. forms a strange echo to Ivan’s Childhood. At the end of Ivan’s Childhood the boy Ivan dies in the hands of the Nazis, but lives on in an idyllic, posthumous fantasy dream/memory where he lives forever on the beach with his friends and mother. Like David, Ivan’s most idyllic memories center on his mother. In A.I. David achieves his idyllic ‘dream’ of being loved by his mother (if only for one day) as an alien induced materialisation based on a lock of her mother’s hair that was kept by his mecha Teddy Bear (and David’s own memories of her mother)

7) Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931, plus countless other remakes and sequels, and of course, the Mary Shelley novel from 1818). This story originated one of the most iconic and often used science fiction themes: that of the scientist playing the ‘overachiever’, who does what is the purveyance of God, to create human life from nothing. Professor Hobby plays the role of the God-like Victor Frankenstein, who creates life out of computer parts; the Frankenstein story also deals with the theme of parental responsibility. Once he creates his offspring, what does he do to shepherd him (or her) into the world? What in turn, are the responsibilities of the child to his or her parent? In the 1964 Hammer The Evil of Frankenstein, the monster is found frozen in a block of ice, and is thawed to life. This plot point is exactly what occurs with David, after he is frozen underwater for some 2000 years and is brought to life with the ‘illuminating’ touch of an alien’s hand (the use of ‘illumination’ to revive David also echoes the Collodi story The Adventures of Pinocchio).

8) La Jetée is another major reference point for A.I.. It is invoked in two senses: David is like the tragic hero from Marker’s film, who asks the super-intelligent future human race to sent him back to the past rather than the future, so he can live with the woman he loves; David is granted a similar wish by his alien protectors, who are an advanced race of Mecha, to be transported (in mind) back to the past life with his mother Monica, to live out a moment of perfection; the second possible allusion to La Jetée references the single moment in that earlier film where we still photographs give way to live action film: the action involves the said woman, lying asleep in her bed, slowly opening her eyes after a series of slow lap dissolves, we assume, in the presence of the hero; the framing and lighting of David’s mother, when she wakes up to David lying next to her, recalls this defining moment from La Jetée.

9) Of course, contact with benign aliens recalls Spielberg’s own science fiction classic Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977).

10) Much of the alien face and body makeup and special effects harks back to the android characters from Westworld (Michael Chrichton, 1973).

11) The night time set design of the exuberant downtown city space where we first meet Gigolo Joe (Jude Law, who looks amazingly well-suited to playing a mecha sex toy model!), Rouge City has echoes of Blade Runner (1982) and Absolute Beginners (Julian Temple, 1986).

12) The influence of Blade Runner can be felt elsewhere, as in the scene where the replicant Roy Batty (played by Rutger Hauer) returns as the prodigal son to meet his maker (his God), the genius designer and owner of the Rydell corporation, Dr. Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel). This is strongly echoed in A.I. in the scene where David, at the end of his journey, returns to meet his maker Professor Hobby. The outcomes are however vastly different. In Blade Runner Batty returns to ask his maker why he was hard-wired with a brief life span of seven years, and ends up crushing his maker’s skull. In A.I. David returns for confirmation of his own uniqueness as a robot, and is distraught, to the point of attempted suicide, to learn that he is but a prototype of many ‘David’s’. With the pan of the camera along Hobby’s night table and a family photograph of Hobby with his son, David (and we) learn that David has been created in the image of Hobby’s own son. “David the robot exists as a living tombstone for the real David, as an eternal sign of human loss” (Dillon, 132). Hobby’s creation is successful, but too successful, for poor David’s emotional connection to his mother (odd that his love is drawn exclusively to his mother and not father, who in fact is the one who initiated the purchase of David) is too all consuming to the point of being ‘unhealthy’ (can this over-sentimentalism toward his mother be seen as an unintentional auto-critique on Spielberg’s part toward his own tendency to over play emotion and sentimentality?). In an moment of pure irony, David does finally achieve his goal of being unique, just not in the manner he had anticipated. When David is thawed out from his two thousand year slumber by the evolved alien form of Mecha, after the human race has died out, the aliens treat him as a ‘unique’ being because he is the last specimen to have known living people; like the tragic hero in La Jetée, whose powerful memories of pre-apocalyptic earth are used by the remaining humans to communicate with the future, the evolved Mecha aliens cherish David as a ‘last survivor’. As they say, “You are the enduring memory of the human race, the most lasting proof of their genius. We only want for your happiness. David you’ve had so little of that.” While some detractors of the film have pointed to the ending as being typical of Spielberg’s sprained optimism, a closer analysis reveals an emotional feeling quite different from joy or feel-good happiness. Yes David does get to live one perfect day with his mother, unfettered by any competitor for his attention, her son Martin, her husband, or the quotidian aspects of the every day. But at what cost and what context? Robot David has long outlived everyone, his ‘real’ father Professor Hobby, his surrogate mother, father and half (?) brother Martin, the whole human race. As Dillon wonderfully writes, “The conclusion, in which the robot ‘becomes a boy’ in the presence of his long-dead mother, is the final aching impossibility. The teddy bear marching across the bed is a cloyingly Spielbergian touch, but even that cuteness cannot mask the powerful impression of evanescence at the end. Surely this is the fairy tale version of Tarkovsky’s Solaris (p. 132). Perhaps it is the Kubrick influence, but Dillon argues that A.I. is far from a reassuring and redemptive take on history, memory and time; and that it is the only one of Spielberg’s post 1990s films that “represents a dislocation between past and present” (p. 132). In comparison, Spielberg’s films Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List, Amistad and Saving Private Ryan “all circle around ‘film’s loving memory,’ and the ‘redemptive power of cinema….all idealize the continuity between past and present…offer cinema as a salvic witness (p. 132).

To conclude this study of A.I.??’s curiously rich allusions to SF cinema, in his fascinating book on the impact of Tarkovsky’s ??Solaris on contemporary American cinema, The Solaris Effect: Art and Artifice in Contemporary American Cinema_, 2006, Steve Dillon writes of A.I., “…A.I. may well be considered a cinematic reenactment of remembered film images” (p. 122). A.I. enacts a wonderfully conceived manifestation of self-reflexivity, a “striking overlap between form and content” (p. 137). Citing visual effects supervisor Dennis Muren from one of the DVD extras, Dillon writes, “…the last section of the movie is almost entirely computer generated, and in the story only computers have survived. This overlap seems suggestively self-reflexive, and therefore readable, but we still need to decide what the film might be saying when it self-consciously refers to itself” (p. 137).

In terms of philosophical/spiritual ideas, the film is most closely aligned with a Judeo-Christian world-view (resurrections and Christ figures abound), but other myths and ideas are also invoked, like Homer’s The Odyssey (the bulk of the film is David’s quest to find the Blue Fairy, and subsequently his mother). While the alien’s explanation to David (spoken by Ben Kingsley) at the film’s end of the impossibility of repeating his life with his mother, because of time/space laws, recalls Henri Bergson’s philosophy of time and memory, namely that every event from the past carries on through memory traces across space and time, but that no moment in time can ever occur again; each moment in time is a unique moment (the question of uniqueness is also paramount in A.I.).

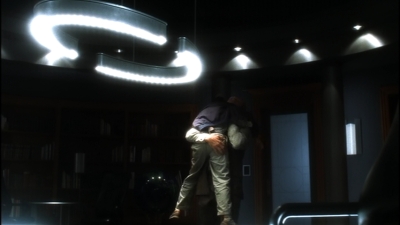

Regardless of their debatable social or political merits of Spielberg’s films, he has undisputed ability with the use of pure cinematic technique, style, and flair. I’ll conclude with some visual stills examples of his clever and visually interesting iterations on the circle motif, which evolves throughout the film in its functional meanings, at times simply serving to isolate or highlight David in the frame, grant him a hallowed, spiritualized presence, or represent the grand ‘circular’ path of David’s journey, which begins with his ‘imprint’ of ‘belonging’ to Monica and ends back with Monica.

Circles Upon Circles

Overhead Guiding Lights

Monica and David in the ‘blue circle of love’

Circles of knowledge (the computer & Dr. Know)

Even Monica’s lock of hair

The mask of identity

The film comes full circle: revisiting time and space

Random Circles:

Bibliography

Steven Dillon. The Solaris Effect: The Art & Artifice of Contemporary American Cinema. Austin: The University of Texas Press, 2006.