The Art of the Interview Book

The great American novelist D.H. Lawrence once wrote, “Never trust the teller, trust the tale. The proper function of a critic is to save the tale from the artist who created it.” The implication in the first part of the quote is that the critic should not take the artist as the final word on the meaning of his or her piece of art. If I were to take this quote and apply it to the film critic, I would add some reasons for why the above maxim may be heeded. First of all, certain filmmakers (and artists) are notoriously tight-lipped about their art, either because they prefer to leave things up to the viewer to discern, or because they prefer not to talk about their art for a variety of other reasons (indifference, disinterest, etc.). In some cases the filmmaker may be afraid of ‘spoiling’ the pleasure of watching their film unadulterated. From Lawrence’s perspective, either the artist can’t be trusted to be honest about their art, preferring to be disingenuous, or they don’t have the proper critical perspective from which to discuss their art. In some respects Lawrence is prefiguring the position made famous by Roland Barthes and Post-structuralism: ‘the death of the author.’ In Post-structuralism the ‘aura’ surrounding the voice of the author is removed in favor of multiple meanings that can be attributed to the “Birth of the Reader” (with “reader” understood in its broadest sense to mean varying cultural, historical, and political perspectives).

As a critic I have always been taken aback by a critical perspective that does not at least listen to what a director might have to say about their art, and Offscreen has always been a strong believer that an engaged discourse between a (willing) director and a willing (i.e. interested and informed) interviewer can result in a useful and at times enlightening dialogue. In the best of cases, the dialogue can result in lessons learned for the interviewer, the reader, and even the filmmaker. As someone who has conducted a fair share of interviews, I offer some common sense qualities that make a good interviewer (nothing earth shattering in what I’m about to outline): a relaxed manner, being well researched and prepared with questions (always have more than you’ll need), being at ease with whatever recording method you are using (nothing turns off an interviewee more than seeing you fumble about for tapes, batteries, paper, pen, etc.), being attentive and a good listener, being spontaneous and not afraid to veer off the ‘script’, and offering to pay for their beverage of choice (hopefully this doesn’t lead to a dozen hard drinks!)

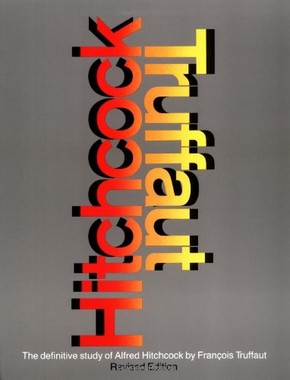

With cinema being such a relatively young art, the discourse of cinema has not yet cultivated the confidence to speak without the voice of its creators. And from a simply practical standpoint, being a younger art means that there is a good chance that the creator is still alive (not the case with, for example, a scholar of Gothic literature, or Shakespeare). On the other hand, there hasn’t been a clearly defined template of the director interview book, although there has been a long tradition of interview books going back to the immediate period following the rise of the auteur theory in (first) Europe (first with Andre Bazin and the Cahiers du cinema group in the late 1950s, early 1960s) and North America (with the publication of Andrew Sarris’ The American Cinema in 1968). These two moments coalesced in the publication of what is still seen as one of, if not the best, interview books, Hitchcock/Truffaut, first released in French in 1966, and then in English one year later. Being both a critic and a filmmaker, Truffaut understands both disciplines, and was able to blend the sheer love of Hitchcock’s work from a director’s standpoint with the necessary critical distance and objectivity. At just over 250 pages, the Hitchcock/Truffaut book is a detailed chronological exploration of Hitchcock’s art and craft that is still one of the single best places to learn about Hitchcock. At moments, and there are many, Hitchcock is clearly inspired by the interest and breadth of understanding shown by Truffaut, and responds with acute detail to technical, thematic, and stylistic issues. Freudian scholars must have felt justified reading Hitchcock himself refer to a shot as “the phallic symbol”! (p. 108) Perhaps it is because Truffaut was a filmmaker, that the best parts of the interview deal with films that had a certain technical quirk or challenge (such as the limited sets of Life Boat and Rear Window, the mobile camera, long takes, and set designs of Rope and Under Capricorn, the 3-D technology in Dial M for Murder, etc.). Was this the first place where we learned about the now famous track out and zoom in trick in Vertigo ?

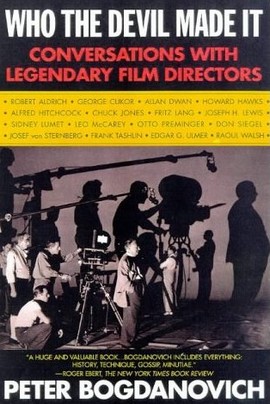

One year before his seminal 1968 American Directors Sarris edited an invaluable collection, Interviews with Film Directors, which contained interviews with forty key American and International directors taken from a variety of previously released sources. It is a book I regularly return to when looking for prize quotes from important directors. Greatly influenced by Sarris, and following in the footsteps of Truffaut, is American critic-turned-director Peter Bogdanovich, who has continued to act as a film historian after establishing himself on the ‘other side’ of the craft. Bogdanovich has specialized in books/interviews with the old masters (John Ford, Howard Hawks, Orson Welles, Fritz Lang, Alfred Hitchcock, Allan Dwan), with two of his interview books, John Ford (1968) and This is Orson Welles (1992) now considered classics that have gone through many reprints and have been translated into many languages. Much of his interview material is compiled in his 1997 release, Who The Devil Made It: Conversations with Legendary Film Directors, which has a follow-up book on actors, entitled Who the Hell’s in It: Conversations with Hollywood’s Legendary Actors (2004). Like British historian Kevin Brownlow, Bogdanovich has expanded his written interview material into documentaries, including his seminal Directed by John Ford (1971, revised in 2006), a 3-hour TV special on Natalie Wood (The Mystery of Natalie Wood (2004), and a docudrama on the hard-hitting Cincinnati Reds baseball superstar Pete Rose and his legal battles over gambling with major league baseball, Hustle (2004). Bogdanovich is regularly featured on DVD special features, where he draws on his vast interview experience to elucidate film history.

An interview book in the tradition of Bogdanovich is Joseph McBride’s wonderful 1982 Hawks on Hawks, published by the University of California Press. In this book the usually reticent Hawks opens up with some wonderful bits of insider material on the greats of Hollywood (Cagney, Bogart, Monroe, Ford, Grant, Wayne, Toland, Hepburn, etc.). Structured chronologically and thematically, as you read Hawks on Hawks you can feel history coming to live.

The idea of titling an interview book with the ‘name’ on ‘name’ was picked up some ten years later by the British Publisher Faber & Faber (and Alfred A. Knopf in Canada) and has continued with a series of individual books devoted to a single director, with each volume edited by a different person. The Faber & Faber series has become an invaluable source for the inner workings of filmmaking. To date the series has included an impressive cross-section of the most relevant narrative filmmakers of their time, including Altman on Altman, Mike Leigh on Mike Leigh, Gilliam on Gilliam, Loach on Loach, Hitchcock on Hitchcock, Herzog on Herzog, Cronenberg on Cronenberg (in a revised second edition), Lynch on Lynch (in a revised second edition), Cassavetes on Cassavetes, Kazan on Kazan, Almodovar on Almodovar, Schrader on Schrader, Kieslowski on Kieslowski, Scorsese on Scorsese, Burton on Burton, and Woody Allen on Woody Allen.

Faber & Faber has also published a side series edited by John Boorman and Walter Donohue, Projections, with each new edition (up to 15 and counting) giving voice to directors and actors and technicians expressing their views on the art and craft of filmmaking.

The interview book has become so popular that it has splintered to include gaps that might be considered a more niche market, like Scott MacDonald’s series of interviews with Independent and Experimental filmmakers, A Critical Cinema, which is now up to Volume 5 (which MacDonald thinks might be the last). Although the focus is mostly on North America, MacDonald has done lovers of Experimental cinema a great (and historically important) service by interviewing some of the most important post-world war 2 experimental and avant-garde filmmakers: Bruce Conner, Ken Jacobs, Michael Snow, Hollis Frampton, Stan Brakhage, George Kuchar, Kenneth Anger, Yvonne Rainer, and Ernie Gehr. For an interview with Scott MacDonald, click here.

Closer to home, Concordia University Professor Mario Falsetto has specialized on interviews with Independent (mainly American) filmmakers, with Personal Visions: conversations with independent film-makers (1999), Personal Visions: conversations with contemporary film directors (2000), The Making of Alternative Cinema (Two Volumes, 2008), the first volume by Falsetto, and Dialogue with Independent Filmmakers (2008). Across these books Falsetto has interviewed an impressive cross-section of important contemporary directors who have not received the same level of critical exposure as more mainstream directors. These include Neil Labute, Sam Mendes, Gus Van Sant, Alexander Payne, Anna Campion, Michael Almereyda, Tom DiCillo, Nicholas Hytner, Michael Radford, John McNaughton, Michael Tolkin, Alan Rudolph, and Alison MacLean.

Although biased by the omnipotence of the auteur principle, the interview format is not restricted to directors, and indeed, as an antidote to the auteur notion, recent years has seen an increase in interview books on actors (see below), editors (First Cut: Conversations with Film Editors, ed. By Gabriella Oldham, University of California Press, 1992, The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing, Michael Ondaatje, Alfred A. Knopf, 2002), cinematographers (see below) and screenwriters (Patrick McGilligan’s “Backstory” series of interviews with screenwriters, now up to volume 4). A pioneer in this field is Leonard Maltin’s excellent Dover Publications The Art of the Cinematographer: A Survey and Interviews with Five Masters (1971) which interviews cinematographers Arthur Miller, Hal Mohr, Hal Rossen, Lucien Ballard, and Conrad Hall. Unlike recent interview books which are all text, Maltin’s book is equally valuable for its wonderful production stills which give some insightful views on the nuts and bolts of filmmaking. A companion piece to Maltin’s book, which covers a wider breadth, is Masters of Light: Conversations with Contemporary Cinematographers edited by Dennis Schaefer and Larry Salvato (1984, University of California Press). At over 350 pages the book includes detailed interviews with DP stalwarts Conrad Hall (the only carry-over from Maltin’s book), Owen Roizman (The Exorcist), Cuban Nestor Almendros (which includes a wonderful section where he discusses the almost all-natural lighting in Malick’s Days of Heaven), John Alonzo, John Bailey (who has an invaluable commentary track on the Sunrise DVD where he discusses the lighting and camera genius of that film), Michael Chapman (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull), Bill Fraker, Laszlo Kovacs, Italian DP’s Vittorio Storaro and Mario Tosi, Haskell Wexler, Billy Williams, Gordon Willis (who discusses his masterful lighting of the first two Godfather films), and Vilmos Zigmond. What you get in this book is not only technical matters on film stock, lenses, camera apparatus, and lights, but insight on how these technical matters often impact on questions of style and aesthetics, plus the working relationship between a director and cinematographer, and some fascinating tales and insights. As an example, I often recount Bill Fraker’s amazing anecdote about a particular shot in Rosemary’s Baby, on page 138-139, where he praises Polanksi for his ability to control and direct an audience’s attention through framing and background space. In the scene in question Mia Farrow is in the foreground front room and Ruth Gordon is in the background bedroom sitting on the bed talking on the phone. Polanski wanted Mia’s POV on Ruth, and staged it with the bedroom doorjamb cutting off Ruth Gordon, leaving only her back visible, while we hear her voice. Fraker responded to Polanski, “You can’t see her,” and Polanski replied, “Exactly, exactly!” Flash forward a few months later and Fraker and Polanski are at a screening of the film. The scene comes and, according to Fraker, “Then you cut to see Ruth and you cannot see her; you can only see half of her and fifteen hundred heads in the theatre lean to the right to see around the doorjamb. Now, that’s the power that Roman has” (p. 139). Say what you will, but this is the type of knowledge that sheds enormous light on the art and craft of cinema and can never come strictly from a critic’s eye.

The art and craft of acting, often one of the hardest areas of film to write about critically, has also been getting a lot of attention of late. At the forefront of this is another Concordia University professor, Carole Zucker. Since the late 1990s Zucker has written a variety of books that give an insider’s (Zucker has studied from some of the best acting teachers and performed herself) perspective but with a theoretical distance that comes from Zucker’s academic background. Her first book was Making Visible the Invisible: An Anthology of Original Essays on Film Acting (1993), which includes essays on acting in silent cinema, the documentary, the musical, the French New Wave, and specific films/directors such as Bresson, Bertolucci, Sternberg, and Keaton. This was followed by Figures of Light: Actors and Directors Illuminate the Art of Film Acting (1995), which is split between actors (including Eli Wallach, Tommy Lee Jones, Christine Lahti, John Lithgow, Lindsey Crouse) and directors (Bob Rafelson, Sidney Lumet, John Sayles, Karl Reisz); In the Company of Actors (1999), which includes performers from the worlds of film, television and theatre (including Eileen Atkins, Alan Bates, Simon Callow, Judi Dench, Brenda Fricker, Nigel Hawthorne, Jane Lapotaire, Janet McTeer, Ian Richardson, Miranda Richardson, Stephen Rea, Fiona Shaw, Anthony Sher, Janet Suzman, David Suchet, and Penelope Wilton), and Conversations with Actors on Film, Television, and Stage Performance (2002), which is broken up into American (Lindsay Crouse, Richard Dreyfuss, Tommy Lee Jones, Christine Lahti, John Lithgow, Mary Steenburgen) and British actors (Tom Conti, James Fox, Kerry Fox, Helen Mirren, Roshan Seth, Peter Ustinov).

I’d like to highlight a recent player in the interview book format that has quickly set a very high standard for the interview format book, the “Conversations with Filmmakers Series” from the University Press of Mississippi/Jackson, with Peter Brunette as General Editor. The series first came to my attention with the release of a book on my favorite director, Andrei Tarkovsky: Interviews, edited by John Gianvito, in 2006. Even for someone like myself who had an extensive catalogue of essays on Tarkovsky, I was struck by how many new pieces were unraveled by editor Gianvito, including many interviews that were previously unreleased in English and translated here (from either French, Russian, or German) for the first time. And I was happy even for those magazine interviews I already had as photocopies scattered about in folders because it is so much more convenient to have them all in one book. Tarkovsky also makes for a great interviewee, whose irascibility often comes to the fore when he gives his interviewer a piece of his mind if a particular question upsets him. Like for example Thomas Johnson, who irks Tarkovsky to no end when he suggests a kinship between him and Spielberg because “he’s also fascinated by children.” Tarkovsky replies, “By asking this question you demonstrate that you have no idea what you’re talking about. Spielberg, Tarkovsky…it’s all the same to you. Wrong! (p. 174)

Having now read four books in this series –entries on Tarkovsky, Atom Egoyan, Hal Ashby, and Guy Maddin– I can say that one of the strengths is in the work of the individual editors, who have managed to scour and compile well balanced, complementary interviews from well known or established, easy to track down sources, but also more obscure, hard to find sources. I am also glad that the series’ editorial policy does not have a bias against online publications, and am happy to say that two of the books I’ve read (Egoyan and Maddin) have reprinted interviews from Offscreen. Each book in the series begins with a longish introduction by the editor, a chronology, and a detailed filmography, before the chronologically ordered interviews.

The four books I have read don’t begin to scratch the surface of the mile long and growing list of books in this wonderful series. I’ll mention a few to whet your appetite, but the list is so long that I’ll simply encourage you to visit their website (linked below) and discover the impressive roll call yourself: Robert Aldrich, Albert and David Maysles, Arthur Penn, Bernardo Bertolucci, Billy Wilder, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, Michelangelo Antonioni, Federico Fellini, Quentin Tarantino, Ousmane Sembene, Orson Welles, Satyajit Ray, and on and on.

I’d like to conclude with a few thoughts on the Guy Maddin interview book in the University Press of Mississippi “Conversations with Filmmakers Series.” Maddin is one of those rare directors whose interviews are arguably more entertaining that his films (and don’t get me wrong, I’m a fan and love his films)! He is a perfect subject to conclude on because he perfectly reflects the opening words of warning from D.H. Lawrence. Clearly, Lawrence’s refrain “Never trust the teller, trust the tale” has no better fit than Maddin, who is notorious for creating his own personal mythology by inventing or exaggerating personal life story details. Editor D.K. Holm opens his introduction on Maddin with a Freudian anecdote about a patient who recounts a surrealistic dream to his analyst, who replies, “Ah. Very interesting.” Then the patient reveals that he lied, and the analyst adds, “Ah, even more interesting! Holm relates this to Maddin’s own penchant for twisting and embellishing the truth. For example, when talking about Renoir’s La Chienne he says that he planned to watch it because of Scarlet Street (a remake of La Chienne), a film which he claims to have, “…watched [that movie] eighty times over a weekend once” (p. 32-33). I’m not a math whizz but even I can tell that such a feat would be bending the laws of time. As Holm writes: “It gradually dawns on the reader that, charming as he is, Maddin is a fantasist, a trickster, a bit of a practical joker. But the result is to make the director even more interesting, because his fantasies can be more instructive that straightforward fact” (p. ix). Freudian indeed!

Publisher Links:

University Press of Mississippi