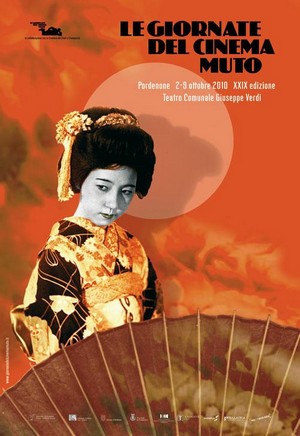

The 29th edition of the Giornate del Cinema Muto

Silent film festival in Pordenone, Italy, October 2010

Surprisingly, given that this year was the 9th time I have attended the great silent film festival in northern Italy, I have never reported on it for Offscreen. I am always excited about attending the Giornate, which is consistently one of the finest film festivals in the world, and the 29th festival was surely one of the best ever, with so many discoveries. And so I felt compelled to report on some of the highlights.

One of the best features of this year’s Giornate is that it was possible to see every single film on view, if one wanted to. There were no competing venues, and although I usually take at least one of the eight days off to visit Venice or another of the region’s historic cities, I couldn’t find the space this year as there were so many exciting programmes. Among these was a very first Brazilian programme of ethnographic/exploration documentaries entitled “Silence of the Amazons,” eight French “making of” films, a small tribute to MOMA and Britain’s National Film Archive, celebrating “75 Years of Film Archives,” an important programme of early French comedies, entitled “French Clowns 1907–1914,” as well as the general sections, “Special Events,” most of which were accompanied by orchestras of various sizes and types, and “The Canon Revisited -2.” The French Clowns series was largely disappointing, in part because the films were scheduled alphabetically by comic actor, from “Anatole” and “Babylas” to “Zigoto” (Lucien Bataille) and “Zizi,” rather than chronologically, which would have made much more sense. Also in order to present less well-known comedians, the programme was very light on Max (Linder)—only three films—and Bout de Zan (René Poyen)—two films—and very heavy on others, such as the surprisingly crude and unimaginative Boireau (André Deed)—16 films—who dominated the second and third sets of screenings (and turned many of us away from others). The second version of The Canon Revisited, after last year’s successful attempt at looking again at some films which may have been considered canonical in the past, if only on a national level, enabled me to see two amazing silent films for the first time: Giovanni Pastrone’s Il Fuoco (Italy, 1915) starring the incredible “diva” Pina Menichelli, who, in Linda Williams’ program notes “is pure unadulterated femme fatale,” and Piel Jutzi’s Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück (Mother Krause’s ??Journey to Happiness?, Germany, 1929). The latter begins with shocking documentary footage of the destitute Berlin-Wedding district proletariat, and after a pessimistic conclusion to the fictional melodrama, the film ends with shots of protestors’ marching feet scored to “The Internationale.” Remarkably, a local marching band entered the orchestra pit, and members of the audience rose to sing the communist anthem.

In Pordenone, silent films are never silent, and one of the glories of the festival has always been the diverse range of musical accompaniment to be heard. Among the most enjoyable this year was Günter A. Buchwald (piano, violin), Frank Bockius (drums) and Romano Todesco (double bass) playing Buchwald’s score for Shakhmatnaya Goryachka (Chess Fever, USSR, 1925), Vsevolod Pudovkin’s first, and hilariously comic film, and the original 1926 score for Alberto Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures (France, 1926), played by Maud Nelissen’s trio. The Orchestra Mitteleuropa’s performance of Carl Davis’ score for the closing night screening of William Wellman’s Wings (US, 1927) was also memorable. Throughout the festival the piano playing was of a consistently high standard, including the work of Donald Sosin, John Sweeney and Stephen Horne. It was thanks to Carlos Roberto de Sousa, the director of Journada Brasileira de Cinema Silensio in São Paulo, now in its fourth year, that four Brasilian films were shown, and the longest of them, No rastro do eldorado (In the Wake of Eldorado, 1925) directed by Silvino Santos, was accompanied by two Brazilian musicians, Angela Nagai and Gustavo Barbosa Lima playing a variety of aboriginal instruments. My favourite film in this section though was Thomas Reis’ Viagem ao Roroimã (1927), which, as its title suggests, excitingly takes us along the Amazon and then the Rio Branco, ending with a climb up the spectacular Mount Roroimã, on the border of Venezuela, the natural location that was the inspiration for last year’s Hollywood blockbuster animation success, Up.

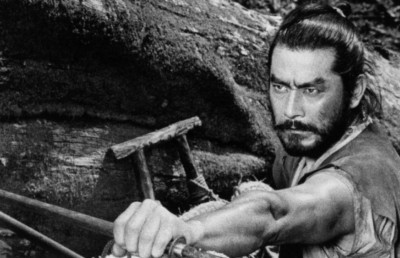

The real draws this year, and the main attractions for me were the programmes dedicated to “Three Soviet Careers,” Room, Kalatozov and Push, and “Three Shochiku Masters,” Shimazu, Shimizu, and Ushihara. Both sections included the work of a film director, virtually unknown outside of their respective countries—Ushihara (Japan) and Push (Georgia)—and both provided cinematic revelations. I knew of Abram Room, but I’d never even seen his best-known and most popular film, Tretya Meshchanskaya (Bed and Sofa, USSR, 1927), which was, for me, a revelation in its frank depiction of Soviet domesticity, where in cramped living quarters, an affair develops between Liuda (Ludmila Semenova) and Volodia (Vladimir Fogel), a friend of her husband, Kolya (Nikolai Batalov). Bed and Sofa is also remarkable for its delightful, documentary-like portrayal of 1920s Moscow. All five of Room’s extant silent films—only one is lost—were shown at the Giornate, including Yevrei na Zemle (Jews on the Land, USSR, 1927), albeit without sub-titles. Room was a Lithuanian Jew, and he was hired to make a positive documentary on the resettlement of Soviet Jews on collective farms in the Crimea (Ukraine). Apparently, an uncredited Vladimir Mayakovsky was responsible for the comic aspect of the intertitles, which were officially attributed to scenarist Victor Shklovsky. One of the most surprising scenes in the film involves the “now productivized” Jewish settlers rearing pigs, very much against tradition! The unknown Lev Push, born in St. Petersburg, began working for a private, Georgian film distribution company in Tbilisi, 1916, and by 1925 was established as an editor for Goskinprom, the Soviet Georgian film studio. His first two films as a director were shown, Giuli (Georgia SSR, 1927), co-directed by Nikolai Shengeleya, and Boshuri Siskhli (Gypsy Blood, Georgia SSR, 1928), both of which were shot by Mikhail Kalatozishvili, later known as Kalatozov. Perhaps the most remarkable discovery of the 29th Giornate was Lursmani Cheqmashi (The Nail in the Boot, Georgia SSR, 1931), directed by Kalatozov. If any further evidence were needed that the director of The Cranes Are Flying (USSR, 1958) and I am Cuba (Cuba/USSR, 1964) was a true visual auteur, then The Nail in the Boot provides this. From the film’s dramatic opening where an armored train is shown rushing over a bridge and towards the camera, Kalatozov’s trademark visual style is evident: low and oblique angled camera and reflected sunlight on metal increasing the sense of depth and dynamic, aggressive movement. A soldier (Alexandre Zhaliashvili) is sent to divisional headquarters to warn that their train is under attack, and a series of low angle, moving camera shots reveal his struggle to cross a barbed wire fence, when a nail in his boot hampers his movement. Again the gleam of metal—nail and wire—in the sunlight has a major visual effect, here accentuating the danger and tension of the soldier’s predicament. He doesn’t make his deadline, and on trial near the end of the film, the soldier makes the case for shoddy workmanship putting the homeland in danger. Although Kalatozov’s film was, arguably, politically sound, even astute, it was attacked for its lack of clarity and formalism, and banned from exhibition. It was eight years before Kalatozov was able to make another film, and this, the very first retrospective of Kalatozov’s five extant films as director and/or cinematographer—including the well-known Jim Shuante (Salt for Svanetia, Georgia SSR, 1930), which also suffered formalist criticism, and fragments of the Georgian documentary, Mati Samepo (A Page from a Biography, 1928)—enabled us to more fully understand his struggles to make beautiful films, even though they were clearly pro-Soviet. No less an authority than Kevin Brownlow, who was shortly to receive an honorary Oscar for his work on silent film history and restoration, declared that The Nail in the Boot was a truly major rediscovery (and a film he had never seen before).

On two previous occasions the Giornate had programmed major retrospectives of Japanese films—the 20th (2001) and 24th (2005) editions, in the town of Sacile—and both featured a number of films made by Shochiku in their Kamata (Tokyo) studios. Over 20 such films were shown, including all four extant silent films directed by Mikio Naruse, two “new discoveries” of Yasujiro Ozu shorts, two features and a fragment of films directed by Hiroshi Shimizu, one each by Heinosuke Gosho and Hotei Nomura, and four films directed by the unknown comic master Torajiro Saito. So strong were these programmes that I began to think that the Shochiku Kamata studio of the first half of the 1930s may well have been the most welcoming studio for creative film directors, if not the finest film studio in the world. Having also been treated to a major retrospective of Shimizu’s entire career at the 2004 Hong Kong International Film Festival, I was very optimistic about this very rare opportunity to see more of Shimizu’s silent output and to view copies of the surviving films directed by the leading directors of an earlier generation at Shochiku, Yasujiro Shimazu and Kiyohiko Ushihara.

According to Akira Tochigi, the Curator of Film at the National Film Centre in Tokyo, Ushihara’s films are not even well known in Japan, and of the four films of his which have survived, three have been preserved only through the survival of privately owned 9.5mm or 16mm home movie prints. Two of these, Kaihin no joo (Queen on the Shore, 1927) and Kangeki Jidai (Age of Emotion, 1928), were highly edited and condensed versions of feature films, only 14 and 19 minutes long, respectively. Little can be gleaned from the surviving elements other than that Ushihara was clearly influenced by the youthful dynamism of Hollywood films—he had visited there between January and September, 1926—and that he had formed a charming pairing of Denmei Suzuki and Kinuyo Tanaka. The only work of Ushihara’s that survived in a 35mm print is Shingun (Marching On, 1930). In a symposium on the Japanese series in Pordenone, Mr Tochigi noted that the print came from the Library of Congress (LoC) in Washington, DC, and that, since many old Japanese films were confiscated by the U.S. occupational forces after World War II, it could have been one of these, especially because of its military subject. Alternatively, Shingun could have been amongst a cachet of films held by the LoC, which came from the Japanese-American community in California. Shingun was, by far and away, the biggest project that Ushihara worked on at Shochiku, involving the unusual full support of the Japanese military forces, and, the results, unfortunately, are disappointing, with the aerial and earthbound combat footage falling far short of that achieved in Wings and King Vidor’s The Big Parade (1925), which had served as inspirations for Ushihara. The surviving print of the director’s last Shochiku film Wakamono yo naze naku ka (Why Do You Cry Youngsters?, 1930) was also lower gauge, but, a full-length version of the original, and featured his star pairing, Suzuki and Tanaka as brother and sister. Both of Ushihara’s 1930 films were extremely long—142 and 193 mins., respectively at 20fps—and highly melodramatic. Koga Noda wrote Shingun, and Tokusaburo Murakami was the scenarist of Wakamono yo naze naku ka. Murakami also wrote the scripts for the two long features in the Shochiku programme, directed by Shimazu, Reijin (The Belle, 1930), 158 min., at 18fps, and the epic Ai yo jinrui to tomo ni are (Love Be with Humanity, 1931), 241 min., at 18fps, as well as Shimizu’s longest film to be shown, Ginga (The Milky Way, 1931), 188 min., at 18fps. The plots of all of the films were quite complex, containing numerous characters, and highly melodramatic, while it seems to me that only Shimizu (and cinematographer Taro Sasaki) was able to subvert these excesses with subtle uses of staging and camera framing. For example, when the central male character, Soichi is sick and lying in bed, the camera rarely views him, but focuses instead on his visiting sister, Terue, the doctor and nurses. In a strategy typical of later Ozu films (all made at Shochiku), key narrative elements are sometimes kept off-screen, altogether. Also, typical of Shimizu’s mature style, the camera often tracks laterally, to follow characters on the street, but, also on interior sets. When a group is visiting Ginza at night, a follow track on the street segues through a cut to a female chorus line inside a club, where the camera tracks right, away from the stage to view a group of men entering in the background.

Shimazu was best known for his lightly comic silent films and, thankfully, one of these, Ashita tenki ni naare (May Tomorrow Be Fine, 1929) has survived in a good copy—surviving elements had been kept by the commissioning agency, the Minister of Education. This charming little film is only 61 minutes long, projected at 18fps. Two puppies have been abandoned in a field, and found by two boys, each taking one home. The film follows the different approaches taken by the boys’ families and how the previous owner, a young girl pines after the loss of her puppies. Needless to say the predicament, of how the dogs should be brought up once the girl rediscovers them, is resolved following a field party/carnival competition between the puppies, Jack and Oro to see which one is “best.” Ginga had never been seen in the west, whereas Shimizu’s Minato no nihon musume (Japanese Girls at the Harbour, 1933) has gained a lot of attention since it was included in a Criterion/Eclipse DVD box set of Shimizu’s films. Everyone I talked to in Pordenone was very happy to see it (again), though. The other Shimizu titles, Nanatsu no umi (Seven Seas, 1931–32), shown in two parts, Daigaku no wakadanna (Young Master at University, 1933), Kinkanshoku (Eclipse, 1934), and, Tokyo no eiyu (A Hero of Tokyo, 1935) had previously only been available on Shochiku VHS tapes, with no sub-titles. Thus, the Giornate gave most of us our first screenings of these films, all of which enhance Shimizu’s reputation as a great director, regardless of the material. Kinkanshoku was based on a mass-market novel written by Masao Kume, but screenwriter Masao Arata reduced the narrative complexities, and Shimizu introduced subtle stylistic devices. In the beginning, Seiji Kanda (Shiro Kanemitsu) is returning home from college, and a tracking camera in a shot of a line-up of girls waiting for him is matched with tracking on his train, and then in another shot, tracking along a line of people in the same direction. When he meets up with a friend, walking in the countryside, they jump up to grab a tree branch, and a low position camera frames just their legs as they are swinging. In Tokyo no eiyu a late silent film, and arguably Shimizu’s most stylistically refined silent film, he introduces the use of dissolves to startling effect. This film initially recounts the downfall of a prominent businessman caught in a shady scam. To show the patriarch’s downfall and disappearance, Shimizu (and cinematographer Hiroshi Nomura) sets the camera up in the family home to view a man checking the furniture. The shot dissolves to one of him leaving with an identical framing, and another dissolve to a shot with the camera again in the same position shows furniture being carried out. We are left with an empty frame.

Although the question was raised on the efficacy of including the work of two first generation Shochiku Kamata directors—Ushihara and Shimazu—along with that of a second generation director, Shimizu, which in my opinion really favoured Shimizu, a great deal of credit goes to Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström, the programmers, for bringing us these extraordinary films. Click here for their detailed program notes.