A Conversation with Zhuang Yuxin

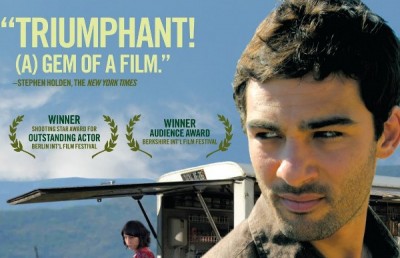

Interview/Conversation with Zhuang Yuxin on the occasion of his first feature film as a director, Ai qing de ya chi (Teeth of Love, 114 min.) being shown in the First Films Competition of the World Film Festival in Montreal at the end of August and the beginning of September, 2007. The session was held in the office of the Chair at the Mel Hoppenheim School of Cinema, Concordia University. The translation was conducted by BFA film production student Aonan Yang and MFA film production student “Fish” Xun Yu.

Zhuang Yuxin is an Associate Professor in the Literature Department of the Beijing film Academy. He graduated from the Literature Department at the Academy in 1994 and became a member of the faculty in the same year. In 2003, he earned a Master’s Degree in film and television studies at the same school.

Synopsis:

The film begins with a scene in which a married woman, Qian Yehong, visits a dentist in 1987 asking him to extract one of her healthy teeth without anesthesia. There is a flashback to 1977 (the year following the end of the Cultural Revolution), where Qian, a Beijing high school student is leading a gang of female bullies. They accuse a classmate Lin Jie of having sex in the woods, who is defended only by a male student, He Xuesong, who hits Qian in the back with a brick. (This leads to her suffering a lifelong back problem.) Strangely it is revealed that He loves Qian, and, as she is coming to terms with this reality he drowns in a nearby river. The second phase in the story occurs circa 1980, when Qian, now 22, is a medical intern at a hospital outside of Beijing. She befriends one of her patients, the much older Meng Han, married with a child, and offers up her virginity to him. She becomes pregnant. But, with the country still living under an oppressive, conservative regime, Qian decides to have a secret abortion, and involves her lover in the procedures. Qian teaches her lover how to perform the abortion using the water sack method, but Meng is caught by secret police while trying to dispose of the dead foetus. In the final phase of the story, set in the mid-1980s, Qian and Meng have drifted apart, and she is now working in a Beijing abattoir, having been kicked out of medical school. Qian meets up with her old nemesis from school, Lin. They are now best friends and Lin introduces Qian to her shy brother-in-law, Wei Yingqiu. They marry, but the relationship doesn’t work out and Qian becomes progressively alienated. At the end, we return to Qian in the dentist’s chair.

Offscreen: If you can talk a little bit about your background and how you started in film.

Zhuang Yuxin: The first big chance in my life was that of going to the Beijing film Academy. Before this I was studying at high school and I was watching some films, and I had the chance to watch some foreign films at a foreign film festival in Beijing where I got to see a film directed by R.W. Fassbinder, The Marriage of Maria Braun. And, I thought, I didn’t know films could be like this, and that they could move me so much, inside.

Offscreen: Actually the film I thought of when I was watching your film, Teeth of Love is Cries and Whispers by Ingmar Bergman, because of the use of fading to red, but also, I think, the concentration on the actors is very interesting, and a little bit different from what I’ve experienced in watching Chinese films.

So if you could talk a little bit about your experiences teaching at the Beijing Film Academy, and your experiences with screen writing and how that developed, and how you got into working in television.

ZY: When I was growing up in the 1980s, my friends and I, we experienced a lack of literature and culture in China at that time and we tended to watch films a lot, and, I also got interested in writing during that time period. I lost myself in writing, and even before going to the Beijing Film Academy, I had written a lot. Now at the Academy I found that people felt that writing “kills” the film. But, I felt differently, that good writing helps a lot.

Offscreen: This is very interesting for me, because, my background was in engineering, I was a draughtsman. I used to draw. So my interest in film has always been visual, which is one of the reasons why I have been attracted to 5th Generation films, because they were very visual, and, I think you are the first Chinese filmmaker I’ve met who comes from a background in literature rather than one of the visual arts, so this is something for me which is different about your work. You are a writer first and then you get into film, so when you were at the film academy did you graduate as a writer? Did you study directing? Did you study everything together, or not?

ZY: Actually, I was very interested in critical theory and I did a lot of film studies. Perhaps it is strange to imagine a Department of Literature inside the Beijing Film Academy, but, in fact there are two main streams there: Script Writing and the Study of Cinema, which included psychoanalytical film theory and various other strands of theory, and I liked that aspect very much. I don’t believe that it is necessary to do professional training in filmmaking in order to become a film director. Back then when I saw Fassbinder’s films, I imagined that I would be a filmmaker and that I would be the “author” of these films, regardless of what I would study, and I didn’t have the notion that I had to study film directing.

Offscreen: The old tradition in Hollywood film is of the “auteur” being a writer-director, so for example, a writer-director like Billy Wilder had a better reputation initially than someone like Alfred Hitchcock who never wrote his own films, so, actually, in the Hollywood mainstream in the 1940s and 1950s, there was more admiration for someone who wrote as well as directed their films, and, then it changed… But, maybe the importance of writing is coming back. (I saw a Chinese film recently where the director tried to make a Hollywood kind of film, and it was awful. The emotions were completely “off,” and the acting was bad, and I thought that if this is the way Chinese film is going, we are in trouble.) So, something I like about your film is that you are dealing with human relationships but not in an excessively melodramatic way. The emotions seem real and the characters seem real. You have a lot of experience working in television with actors. Did you direct in television or did you just write?

ZY: In television I was a writer, and producer and I also worked in the role of distributor. I have my own company, and the reason why I started this company is that there is a market for TV series, and I thought that if I can make some money this way, I could fund my own feature films.

Offscreen: The actors in your film, not just Yan Bingyan, the leading actress, seem very good, and, so it doesn’t seem at all to be like a “first feature,” especially not in terms of the directing of acting, which seems to be very experienced. So, I don’t know where that comes from…

ZY: Perhaps one of the reasons that the film doesn’t seem like a first feature is because of my age. Perhaps I have a kind of maturity; also, it may come from the great experience I have in writing and producing TV series. I have to manage the productions and if there are problems I have, myself to “fill the gaps.” So this way, I have gained some indirect experience. Also I have been thinking about this film for quite a long time, 10 years.

Offscreen: One of the qualities of Teeth of Love, which is why, for sure you would have won a prize had your film been entered in the main competition of the World Film Festival is that it is very mature; there is a great deal of maturity in the construction of the characters in the film, so that everyone can relate to these people as people, but, you also discover some original actions and plot lines, for example, the treatment of the abortion which is unique—the love story develops through the coming together of the couple in the abortion process!! There is real freshness here (as well as a maturity).*

So, I’m curious about the fact that you have your own company because that would not have been possible five years ago, right? Is this kind of opportunity new? Are you able to direct because you have your own company? Can you talk about how things have changed in China in terms of people being able to have their own businesses.

ZY: What happened is that the TV series market was booming, relative to the film business, so that there were opportunities to produce and sell television programmes, and the government became a bit loose in that sense, and then the openness with film came afterwards, in the last three or four years, because of the model provided by TV series. So I formed my own TV company and, more recently I’ve been able to form my own film production company.

Offscreen: Was your film shot on 35mm?

ZY: Yes

Offscreen: Because I know from experience that, in the past it was impossible for such a thing as independent Chinese film: nobody could actually get access to celluloid film (35mm) equipment. You could only make an independent film if it was digital. It was easy to obtain video equipment, but the state controlled 35mm equipment and only people inside the system could access it, so I guess, in your case, because you are in the Film Academy, you were able to negotiate something?

ZY: It is more a matter of money rather than one of politics. About three or four years ago everything opened up, so that everybody can now use 35mm cameras, but the rental is quite expensive which is why most young directors choose to shot digitally.

Offscreen: It looks like 35mm, which is why I wondering how you were able to do that with your own production company. That’s interesting.

I don’t agree with this, but, one of the reviews that I’ve been reading didn’t like the framing story—the dentist part of it—but, for me that was, like, really important. So, one question I have is on the title. Is the Chinese title the same as the English title, Teeth of Love? Because it makes sense in terms of the framing story but also in terms of wanting to suffer pain as a way of experiencing things, so could you talk a little about the framing story involving the dentist…

ZY: First of all, the English title is a literal translation of the English title. Have you read Derek Elley’s review in Variety?

Offscreen: No, but I realize that he does understand Chinese.

ZY: I’ll give you a copy, because he says it is a very bad translation of the title. First of all the title refers to the pain of toothache which is a very concentrated kind of pain, and very strong, perhaps the most painful experience, physically. So this symbolizes the painful experience of being in love with somebody or not being in love with somebody, but being together with them. Then there’s the situation in the film itself where there is the manifestation of a tooth: Qian has a tooth removed and then her lover, when they separate, takes out his tooth. Also there is the idea that “love has teeth” which can “bite.”

Offscreen: And there is pain in the other two stories as well: in the first story with the break, and then the second story with the abortion.

Aonan Yang: And her back pain also.

ZY: I’m not really happy with the results of the beginning and the end, where she goes to the dentist. In the script writing stage, I had a better idea of this scene, but it wasn’t realized as successfully as I had hoped. It would have been different had I managed to shoot the film 10 years ago. So I had to provide titles to situate the film in the period. Secondly, as a scriptwriter you want to experiment with the material… There is a plotline involving dentistry: she is involved with a dentist [PR: she visits him 5 times]. I wanted to create a parallel between what happened to her before and what happens in the “real time.”

Offscreen: We are very used to fragmentation in films, now. We are used to having something happen in a sudden flashback, and we kind of go with that, even if we don’t fully understand what’s happening. I didn’t know who the woman in the dentist’s chair was. I didn’t realize initially that she was the “tough girl” student, Qian, and, there is of course such a big difference; she changes so much over time.

I talked to a few people after the film, and, different people preferred different parts of the film, and people who are younger than me really liked the first episode. For me, the first episode did not ring nearly as true as the second and the third episodes. It’s probably a generational thing. You know, I’m probably much older than the average viewer, and, it was difficult for me to reconcile what I was seeing with what I imagine Chinese teenagers would have been like in 1977, considering what I know of that era.

Was there anything in the first story from your own experience being a teenager in high school?

ZY: First of all, when I showed the film in the Beijing Film Academy and elsewhere in China, young people also liked the first part (which could mean that they don’t like the second and third parts)—laughter—they say, “Oh Teacher, the first part is great!” Perhaps young people haven’t gone through the troubles faced in marriage. My relationship with the first part is that the age of that woman is ten years older than me. But, when I was young; tough teenage women like that were prevalent in Beijing. Actually, that personality was quite common. She is not a special case. Also, I found them to be very attractive. Their character is more like a man…

Offscreen: Yes, in a sense she is more interesting in the first part because she is so tough. But, it is good that she changes, because life is like that: it wears you down…

ZY: There is also a strong comparison between her character and that of another young woman, Lin Jie (Wu Jiaojiao) who is tender, and presented very sympathetically. Normally audience members would expect the young man, He Xuesong (Chi Jia) to prefer her over Qian (Yan Binyang).

Offscreen: Yes, we tend to be very masochistic at that age—more laughter.

I’ve already mentioned how amazingly unusual the abortion story is, so where did you get the idea from of the kind of love being shown through the experience of the abortion. How did you manage to conceive of that part of the film. It is so striking.

ZY: First of all, she actually pushes him into the situation of getting involved in the abortion. But, it was based on simple story I had written before, and I worked it into the film script. Every person has a secret in their life, which is not exposed to the person who is closest to them, maybe the husband, maybe the parents. Usually the parents don’t know the secret life of their child, or vice versa… So, by doing it this way, Qian is exposing the secret part of her life [to her lover] which is revealing the deep truth of her personality, and the most intimate aspects of her relationship….

Offscreen: Yes, this is really brilliant. The idea of being truthful, and that truth is connected to real love, so that’s where the real love in the film is in this section, because of the honesty; and Qian is saying, “this is it; this is the real me, and you have to get involved in this; and he does, and therefore that is the consummation of the love…” This section of the film actually really moves me.

ZY: I put a lot of close-ups in this section, but, I didn’t show any blood, because I wanted to show the person, I wanted to show Qian’s inner state in this situation. I focused on her in this love affair, without making the abortion explicit.

Offscreen: I really like the character of the lover, Meng Han (Li Hongtao) also in this section. While we’ve been talking I’ve been thinking about the connections between the different stories, for example how, in the first part, whereas Qian is tough, the young man, He Xueshong, who tragically dies, arguably turns out to be even tougher than her, and in the second part, she seems to be looking for someone who is stronger than her. Therefore, what on earth is she doing with such a timid man, Wei Yingqiu in the last part. Surely, she can’t love him, and, he doesn’t seem to be interested in her, either. Obviously it is a mismatch, but, we can learn from the other two relationships that this one is not going to work. The relationship is very cold, and therefore it is difficult for audiences to “like” the third part of the film, but, for me, the coldness is absolutely necessary…, it makes sense. But we still feel for her.

Through the concentration on the face, I also thought about television. I have very little interest in television drama, myself. But, it seems to me that Teeth of Love could be great television. I would watch it… You don’t need a lot of dialogue, where we watch the people so intensely, at their faces… It works visually the way the best television is supposed to work, like Ingmar Bergman’s work, which is good to look at, but which has a real intensity of personality, which is very subtle, not necessarily obvious; it’s not overly melodramatic. We spend time with these people, and, we gradually understand what is really going on between them. Actually, I’m not normally interested in material like this, but you drew me in… We start off at a distance—at the school Qian is in the background always, looking on; she is not seen close-up—then we are drawn intensely in the middle of the film, and then set at a distance again at the end, where a disorienting montage sequence allows us to understand her alienation.

Have you got another project that you are working on?

ZY: I have got a number of ideas, but, the realization of them depends on how much money I can get. Some require more funding than others.

Offscreen: Is Teeth of Love in theatres in China right now?

ZY: Yes

Offscreen: Do you have a sense of how it is doing?

ZY: It is not doing badly, but it is not doing great, either. It will play in the different regions of China, and we’ll see how it does there. But, obviously, the box office won’t compare with big budget films.

Offscreen: So, will what you do in the future depend to a large extent on how well this, your first feature does commercially? Do the attendance and the box office actually have an effect on your ability to make another film?

ZY: Even if it ends up doing badly, it shouldn’t affect my ability to get money to make another film. I am well known, and fairly well respected. Getting money doesn’t only depend on the financial success of films but also on the connections one might have in the industry. Also, it depends a lot on my own experience and my next project, itself. Will it attract any interest?

Offscreen: In terms of the actress, Yan Bingyan, she must be very happy because she had such a “full” role. I am thinking that most of the Chinese actresses we know are very glamorous figures, who either don’t have the same kind of acting talent, or, at least it is not being revealed in the way it is here. For me, it is good that we are exposed to a real acting talent here, and we need more of that, I think. We have a counter-example to someone like Zhang Ziyi… For a film to be successful outside of China, it seems there has to be a young, glamorous Chinese actress.

Teeth of Love didn’t win an award at the World Film Festival, but Yan Bingyan won the Best Actress award (ex aqueo) at the Golden Rooster Awards (the Chinese “Oscars”) at the end of 2007.