Who’s Talking? Who’s Listening?

Toward a Better System of Communication in Abderrahmane Sissako’s Bamako

Cinema’s one-way system of communication conveys a message or experience to a receiving audience. Each message can be conveyed in innumerable forms so that the intended audience receives the message in a specific manner. However, despite this diversity in form and content, many messages come from the same empowered source and thus privilege both those in power and this “top down” means of communication. As Ngugi Wa Thiong’o suggests, “if we live in a situation where the image of the world is itself colonised, then it becomes difficult for us to realise ourselves unless we struggle to decolonise that image. Decolonisation of the mind is both a prerequisite for successful African cinema and it is also the object of serious African Cinema” (95). From this perspective, Abderrahmane Sissako’s latest film, Bamako (2006), addresses the role of the communication process in decolonialisation. More specifically, Bamako asks its audiences to listen to the voices of Africa, compare and contrast these voices with voices of the West, and finally play an active role in forming a new decolonised system of global communication. If communication is at the heart of all cinema, then decolonized communication should aim to create human solidarity.

Sissako structures Bamako around the testimonies of six witnesses to the atrocities that international organizations, such as the World Bank, have inflicted on the African continent through structural adjustment policies. These testimonies not only speak to economic and social issues, but also to the self-reflexive issue of film communication. The nature of the testimonial form itself asks us to listen intently to the powerful discourse on the current state of African society, politics, and economics. As Allen Carey-Webb writes, the testimonial’s “power comes from its directness, its real life immediacy, its evocation of a people in history … They are not biographies because the subjects speak for themselves. They are not autobiographies because they are recorded and written down by a second person. They are not traditional oral histories because they emphasize the experience of the group rather than the perspective of an individual” (44). Through the directness and real-life immediacy of the testimonies, Bamako asks the audience to listen to the voices of Africa when they speak about their experience as a group of people that has been oppressed for centuries. All of the testimonies describe the atrocities at work in Africa. More specifically, they address the number of people expected to die in Africa in the next five years, the exodus caused by privatization of the rail system, the colonization of ideas, and the pauperization of the African continent. The testimonial form, then, asks the audience to listen carefully to these voices of Africa as they plea for a renewed, more humane approach to solving Africa’s problems.

To enable audience members to actively listen to these testimonies, the film features many shots of the trial’s audience. As a result, the film audience can easily identify with the on-screen trial audience. Specifically, during the witnesses’ testimonies, cut away shots feature the faces of trial attendees. Each of these shots is still and usually a medium close-up. As a result, this kind of shot emphasizes personal reactions to the trial proceedings. In almost all cases, the on-screen attendees stare into the camera with expressions that suggest that they not only understand each message’s urgency but also they identify with the speakers. As a result of these shots, the reaction of film viewers to the testimonies mirrors that of these on-screen attendees: we must also must sit and listen intently, for this is not a film of action but a film of the act of communicating vital, immediate knowledge, thoughts, and feelings. Only from this position of active listener can we participate in this portrayal of valid, authentic communication. To truly understand, we must listen to the voices of Africa. When the lawyers give their final summation, the civil lawyer (Aissata Tall Sall) argues that “the balance of world humanity is at stake.” Soon after, the other civil lawyer (William Bourdon), calls for the following sentence: “community service for all mankind for eternity.” These representative voices communicate to listeners not only the need for decolonisation, but also the necessity for decolonising the communication process.

In addition to this plea for better, more balanced communication, Sissako realistically suggests the difficulties in communicating this authentic African voice. At the beginning of the proceedings, an old man comes to the podium to testify about his experience in Africa. The judge tells him that it is not his turn to speak. This rejection attempts to silence a voice that wanted to be heard. Nevertheless, the old man replies, “words are something. They can seize you in the heart. But it’s not good to keep them inside.” This man’s situation is analogous to African people’s desire to be heard but their inability to get others to listen to them. Sissako believes that we should listen to (and thus show respect for) people who have something to say to us. In an interview he says, “the intention to communicate is more important than communication itself. When you decide to talk to the Other, a loving gesture has been made. If somebody wants to speak to me, it means I exist in their eyes” (qtd. in Barlet, n.pag.). Because the court does not attempt to talk with this man or even listen to his testimony, the loving gesture of communication is lost. We have lost an opportunity for authentic communication by not including this kind of disenfranchised speaker in our legal communication system.

To further his argument that we should listen to the voices of the disenfranchised, Sissako suggests that silencing these voices leads to the devastation of humanity. For example, Chaka (Tiécoura Traoré) and the journalist who has been covering the trial sit in a couple of chairs in the courtyard. The journalist asks Chaka to repeat what he said the day before about the horrific state of the African people because the tape had somehow been erased. Chaka replies, “it doesn’t matter anymore.” The loss of Chaka’s voice is the loss of the voice of Africa. In this way, Sissako asks the audience to think about the ways in which the voice of an entire people is repressed and lost. In the end Chaka kills himself. Like many Africans, he believes “it’s too late” so he gives up hope that Africans in power as well as the rest of the world will ever listen let alone affect change.

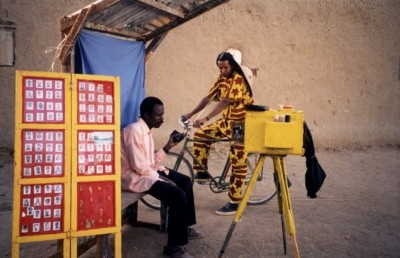

If Sissako asks the film’s audience to consider what it means to lose the voice of a continent, he also asks the audience in the film, the African audience, to consider to whom they are paying attention. For example, after one day of testimonies, two men bring a television into the courtyard where a number of people are gathered to watch the trial proceedings. When they turn on the television, the sign-off of the news program comes on. Then, some technical difficulties leave the host smiling awkwardly on screen. Here, Sissako shows two impediments to communication: first, he suggests that the audience itself is relatively uninterested in the news of their country, and second, the technological infrastructure for enabling communication is inadequate. We cannot blame the audience for not watching the news, but at the same time we know that the news is one outlet for the African voice. Even if people did want to communicate, many Africans do not really want to listen or are prevented from listening by the faulty communication system. In addition, because the film is constantly suggesting the devastating effects of foreign debt, we can assume that the lack of technological infrastructure is indirectly an effect of this debt. In this sense, the World Bank and similar organizations are inhibiting the ability of the African people to produce their own decolonized images and voices.

Immediately after this news program, a cut brings us to an “American movie.” In effect we feel that the African audience is used to the entertainment value of American content instead of actual African news. Sissako also compares the technical expertise of this TV film, “Death in Timbuktu,” with that of the news program that came before. Beautiful, glossy landscape shots and the names of stars appear in this film within a film. The disparity of technical capabilities is obvious here. However, as John Badenhorst argues, “there is a real danger in the continual importing of outside products, however glossy or cost-effective they may be. The local industry cannot immediately compete with the international one, but it is only through the promotion of home-grown efforts that the first steps along the road to a truly indigenous cinema will be taken” (173). If an audience cannot support their own content then the voices of a truly indigenous cinema will be lost. Through these glossy shots, Sissako suggests that African audiences might prefer to identify with images of themselves as portrayed in glossy American films. However, although the TV film is ostensibly about Africa, it is not part of “a truly indigenous cinema.”

As “Death in Timbuktu” goes on, we see that Sissako is overtly attempting to criticize these images and their irrelevance to the people who are watching the film. When the cowboys in the TV film enter the town, one of them shoots a teacher for no apparent reason. At another point a woman who is only carrying water gets shot and her son has to watch this happen. Close to the end of the TV film, three of the cowboys gather in the middle of the town. The forth then comes toward the group laughing and saying that in trying to shoot one person he actually got two. They all start laughing hysterically until a bullet comes from the hero, a cowboy played by Danny Glover, to kill the laughing cowboy, played by director Elia Suleiman. As a result all the other cowboys start running around like chickens with no heads shooting their guns aimlessly. The title then comes up that says “Death in Timbuktu.” The TV show critiques Western genre films and the African audiences that consume them. As Clyde Taylor writes, “the intent of the culture industry has been to concoct an artificial mental landscape harmonious with its needs, to depersonalize its audience into zombies of its economy and addicts of its industrial culture, and to trash, trivialize and erase the natural human cultures that supply its victims” (330). The absurdity of this short program calls attention to American cinemas tendency to trivialize violence and ignore racism. By juxtaposing this absurdity with the urgent testimonies that make up the greater portion of the film, Sissako points out that much of American media is aimed at entertainment and economy rather than authentic indigenous communication.

In addition to this critique of the media, in this scene we also get reaction shots of the African film audience, the “addicts of industrial culture,” to this absurd TV film. For example, as Elia Suleiman tells his “hilarious” story, shots of the African audience demonstrate that they too are laughing at the situation. Again, these shots of the audience contrast with the shots of the serious trial attendees who sit and listen day in and day out. Again, the audience is encouraged to consider both to whom they are listening and the effects of consuming “colonised” media. As Taylor suggests, the media of the industrial culture “erases the natural human culture” by substituting it with “entertainment” that obliquely communicates racist and colonialist beliefs.

Close to the end of the film, Sissako uses two more forms of communication that solidify his plea for an African voice in the name of human solidarity. The first case comes when Zegué Bamba, who was not given a voice to speak at the beginning of the film, stands up, not because he was called upon, but because he felt he had to. Bamba sings an incredibly passionate account of his experience. Notably, the song is not subtitled. The song embodies an “intention to communicate” and is a “loving gesture” when words have failed. We must listen to this powerful non-verbal communication from the heart in order to emotionally understand his frustration. As Ngugi Wa Thiong’o suggests “decolonisation of the mental space has to go hand in hand with that of the economic and political space” (93). In order to change current oppressive systems we must believe indigenous testimonies like that of Bamba even if they do not reveal truths in a way that Western court systems accept. Bamba communicates in a decolonised way and in doing so asks the audience to decolonise their conventional understanding of how truth is communicated. Only from a decolonised mental space can real economic and political change occur; if we are open to it, Bamba’s song tells us as much, if not more, than we can learn from all of the testimonies, evidence, and court rulings combined.

Finally, to end the film, Sissako puts us in the position of Falaï (Balla Habib Dembélé), the videomaker, through the use of a point-of-view shot as seen through his video camera. There is absolutely no sound in this scene except for the camera motor. Through this point-of-view shot the audience becomes an active member in the recording process of Chaka’s funeral. In switching the audience’s role in the process of communication from one of receiving to one of participating in the recording, the film asks that audiences think about their role in the process of communication. What will they say about this death when the shot is done? What words and thoughts could fill the silence during this recording? If we are to create a decolonised system of communication that strives for equality and solidarity we must all be active senders and open receivers with this same goal.

In conclusion, Sissako uses different communication media in the film in order to raise questions about communication itself and the various audiences’ relationships to it. By focusing on the power of the testimony and comparing it to other media, Sissako asks audience members to analyze and criticize their role in the processes of communication. Who is allowed to speak in our world? Who are we willing to listen to? Who do we identify with and support? In the end, Sissako calls for not only a decolonised and indigenous voice for Africa but also world wide solidarity that can exist only if we as speakers and listeners insist on equal, active, and open communication.

Works Cited

“Bamako”. Press Release from Alibi Communications. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

Badenhorst, John. “Power, Cinema and TV in Africa.” Givanni 158-175.

Barlet, Olivier. “Interview: Abderrahmane Sissako.” Africultures (1998). 31 Mar. 2007.

Carey-Webb, Allen. “Auto/Biography of the Oppressed: The Power of Testimonial.” English Journal Vol. 80, No. 4 (April 1991). 44-47.

Givanni, June, ed. Symbolic Narratives/African Cinema: Audiences, Theory and the Moving Image. London: British Film Institute, 2000.

Taylor, Clyde. “Third World Cinema: One Struggle, Many Fronts.” Jump Cut: Hollywood, Politics and Counter Cinema. ed. Peter Steven. Toronto: Between the Lines, 1985. 329-333.

Thiong’o, Ngugi Wa. “Is the Decolonisation of the Mind a Prerequisite for the Independence of Thought and the Creative Practice of African Cinema? Introduction.” Givanni 93-96.