“Unmasking” The Phantom of the Opera

Gala Fantasia 2011

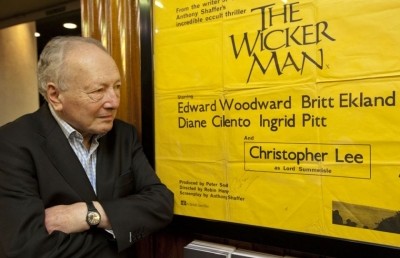

The 2011 edition of Fantasia had the unenviable task of living up to its 2010 inaugural gala presentation of the restored version of Metropolis, which was a stunning success. The programmers did right by returning with another silent cinema classic, The Phantom of the Opera, and while it could not quite scale the lofty heights of the Metropolis event, it was still a worthy sequel. It was always going to be hard to match the added bonus of presenting a restored version of Metropolis that included about 25 minutes of previously thought to be lost footage. The one area where 2011 topped 2010 was in showing a 35mm print, as opposed to the necessary –because of the restoration– digital projection of Metropolis. The 2011 gala was held in the same splendid location, the prestigious Place des Arts concert hall, and back again was an orchestral score conducted by Montreal’s own musical star, Gabriel Thibadeau, who had already composed a special score for The Phantom of the Opera for an earlier Kino video release, a score that was commissioned by La Cinémathèque québécoise in 1992. Purists may have preferred this year’s score to the more experimental score of 2010, but both scores were dictated by the type of film being accompanied, with the futurist/science fiction scenario of Metropolis being more open to musical experimentation.

Like Metropolis, The Phantom of the Opera has a complicated release and production history. So much so that when people claim to have seen the 1925 silent version, what they have ACTUALLY seen is most likely the silent version of the 1929 re-release with synchronized sound and music. From the many sources that have outlined the film’s production history two that I find reliable are the Silent Era website and the excellent book by Steve Haberman, Silent Screams.

From what I can gather from these and other sources about the complex production history of this film, there is a pedigree of five versions (three 1925 silent releases, screened on January in Los Angeles, April in San Francisco, and August-September in New York), a 1929 domestic synchronized sound re-release and a 1930 international synchronized sound re-release). The version which was screened by Fantasia was a silent version of the 1929 domestic sound re-release which included synchronized sound effects and music and some dialogue. In fact, it is exactly the Image Entertainment 1997 DVD release, minus the color tinting. The original general release 1925 version (after two earlier preview screening versions in Los Angeles and San Francisco), first screened in New York on September 25, currently only exists in a 16mm print, and has been made available in the recent Milestone 2-disc DVD release and the more recent Kino Blu-ray. Hence until a version of the 35mm 1925 version is found, any screening of a 35mm print has to be a variant on the 1929 re-release.

Not that this is necessary, but the setting of the film is the Paris Opera House circa 1880. The Opera is being sold by the current owners who are unsettled by the haunting presence of the masked, dark-cloaked occupant of Seat five, Erik (the masked Lon Chaney, better known as the Phantom of the opera). The omnipotent Erik is a puppet master pulling the Opera House strings to serve his single driving obsession: the heart and career of young rising opera star Christine (Mary Philbin), whom Erik coaches and nurtures with Svengali-like control. Christine, who is temporarily kept captive in the Phantom’s underground lair, must choose between her opera singing career, the ‘spirit’ of Erik, and her relentless (and wholly uninteresting!) suitor, Raoul. The Phantom of the Opera has achieved its status as a time-honored dark classic due largely to the performance (and show-stopping, self-designed make-up) of Lon Chaney in the role of Erik, and the outstanding Universal studio sets of the Paris Opera House, its backstage and the labyrinth Opera House underground cellars, docks, chambers, and stone staircases where Erik lives his rat-like nocturnal existence. The backstage and underground sets were designed by Paris born Ben Carré (who gets unique ‘Consulting Artist’ credit). Although shot entirely on the Universal studio back lot, the sets where conditioned by novel (1910) writer Gaston Leroux’s fortuitous visit of the Opera House underbelly –which extended as deep as seventy feet– and Ben Carré’s previous experience working on the original props and backdrops for operas performed at the Paris Opera House. When Christine is lured into Erik’s netherworld through a mirror she and the audience enter a dream-like world of moving life-like shadows, Gothic arches, and womb-like waterways and sinewy tunnels. In these scenes The Phantom of the Opera achieves its defining atmosphere of a morbid, dark fantasy, influenced by such diverse literary works as the 1894 Trilby (mind control), Beauty and the Beast first published in 1740, (the idea of a beautiful damsel being courted by a ‘monster’), Faust (the notion of Erik’s soul being eternally damned), and Edgar Allan Poe’s 1842 Masque of the Red Death (notably the masked ball). There have been countless color and sound remakes and variant reduxes of this classic tale, including the first Chinese horror film, Song at Midnight (1937) and takes by such luminaries as Arthur Lubin, Terence Fisher, Brian De Palma, Dario Argento, and Ronny Yu, but none have surpassed the dark beauty of Carré’s sets and Chaney’s terrifying rendition of Erik, the tortured soul.

According to horror scholar David Sklar in his excellent The Monster Show, Chaney’s run of self-designed physically disfigured characters (in The Miracle, The Penalty, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Phantom of the Opera, The Unknown, London after Midnight, West of Zanzibar) –which earned him the nickname ‘a man of thousand faces”– was a reflection of the many physically deformed World War 1 veterans seen across America and Europe (“disfigurement anxiety”). As in the novel (but unlike later versions which give a cause for Erik’s disfigurement, usually acid) Chaney’s version is thematically richer because of the lack of a cause, which opens his status up to metaphorical readings, such as the noted Sklar’s: “Chaney’s opera ghost was primally, congenitally horrible; birth itself was the monstrosity” (p. 68).

My interest for this essay is to focus on the remarkable scene where the Mary Philbin character (Christine Daae) unmasks Erik, the Phantom. The scene established some of the most iconic and essential ingredients of the horror genre, old and new, the dynamic tension between the woman and the monster, the victim and the villain, beauty and the beast, the lure and the disgust offered by horror, the ‘attraction’ and ‘repulsion,’ and the act of voyeurism (the looker and the looked) so essential to the whole genre. On its own, it is also one of the most interestingly edited scenes in any horror film, notable for the way it:

1) builds suspense

2) alternates between objective and subjective points of view to the benefit of Erik’s sympathy

3) introduces surprising, unexpected, and at times disorienting camera angles

4) employs out of focus shots for drama

Another aspect a close analysis of the editing reveals is something that no other writer has noted: that there are in fact multiple ‘unmaskings’ in this scene.

The scene, which lasts approximately five minutes, starting at around the 48 minute mark, begins with Christine entering Erik’s room from the door behind the organ where he is seated playing. She walks up to him, as he plays on unaware of her presence. This establishes the sense of this being an invasion of Erik’s privacy, and the idea that Christine, a victim, is at this moment, the voyeur and the aggressor: she is sneaking up on Erik. She looks over his shoulder and sees the sheet music, “Don Juan Triumphant.” This foreshadows the theme of ‘triumph’ that will be played out in Chaney’s performance, notably in the way he raises his arms way above his head in a defiant gesture of celebration. After they briefly acknowledge each other, the camera focuses on Christine’s face, as she comes to the decision to unmask him. Again, her face is visible only to us, not Erik, whose back is turned to her. Hence we become complicit with Christine’s decision to ‘unmask’ Erik, who has already warned Christine against doing so (which establishes yet another horror cliché: the damsel who treads where she should not). Her decision to unmask Erik is plain to see for the audience, it is in her performance, the way her brain can be seen churning, her seductive eye movements, which again puts us in her mind but perhaps makes us feel sympathy for Erik because he is unaware of what is to occur. Her gesture increases the act as one of violation of his space and privacy. The excitement and sense of anticipation on Christine’s face as she slowly moves her hands toward his mask is palpable. It reflects a sense of empowerment, as she is in full control of her destiny and has made the clear decision to break Erik’s trust.

The desire to look

Her curiosity is stronger than any sense of propriety or honor. The way she advances and then recoils her hands is also a reflection of one of the greatest theoretical complexes of horror, as elaborated by Noel Carroll in his book The Philosophy of Horror: the way horror fiction works on our simultaneous attraction to and repulsion of the horrible sight, the ‘push-pull’ effect, what Carroll sees as one of the two great “paradoxes of art-horror,” the latter defined as fictional horror: Why would anyone be interested in something unpleasant? and, Why we are afraid of something we know does not exist?

The ‘push-pull’ complex

After a slow build up where she draws her hands to him then away, in medium shot profile, the unmasking occurs, but abruptly, across a shock edit to an objective point of view looking at both Erik’s hideous face and Christine behind him. We actually don’t see her remove the mask, but already see her hand with the mask in it drawn away from Erik’s face. It is a wonderful edit that leaves us with the impression of having seen more than we actually have. What is surprising is that we see Erik’s face before she does. As Linda Williams notes, “…in the famous unmasking scene…we …see the Phantom’s face, this time unmasked, before Christine does. The audience thus receives the first shock of the horror even while it can still see the curiosity and desire to see on Christine’s face” (p. 86). This ‘desire to see’ is rarely given space to women in mainstream Hollywood, and classic silent cinema. As Erik rises to his feet and turns toward Christine, his face ends up off-screen right, and now we see Christine’s late horrified reaction to Erik’s grotesque face, which Carlos Clarens described as a “living skull” (p. 49).

The scream heard around the world

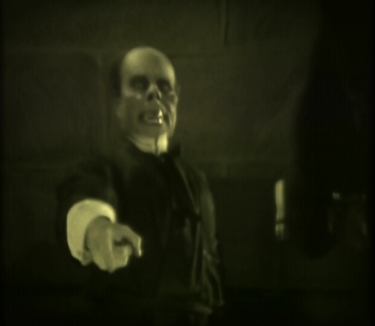

At this point we finally cut to Christine’s POV: a disorienting medium long shot of Erik, his finger jutting forward pointing at the camera/Christine, accusing her and us of this violation of his privacy. What is most striking is that his face is out of focus, as if the filmmakers were reluctant or afraid to give the audience a clear, uncluttered view of his face, too afraid of the shock that Chaney’s outstanding makeup would have on an unsuspecting audience. In some respects, the lack of clarity allows his face to remain partially ‘masked.’

The scene cuts back to an objective shot staged from farther back, with Christine cowering to the ground away from him. It cuts back to the out of focus subjective shot of Erik, in MS; then back farther yet again as Christine has now crawled down two sets of steps, increasing Erik’s physical dominance over her.

Then we cut to Erik’s first subjective POV shot: a high angle looking down at the fallen Christine…

Erik’s first POV shot

…after a cut back to the far shot comes a second striking edit, to an extreme low angle close-up of Erik (from Christine’s POV), as he walks forward into an extreme close-up, then there is a cut back to the high angle shot looking down at Christine.

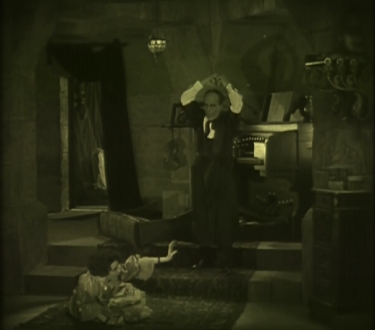

The scene then cuts back to the long shot two-shot, with Erik now raising his arms in triumph. And then the third striking, disorienting edit, to a bird’s eye view angle above Erik’s head (his hands still triumphantly raised over his head, forming a perfect graphic match).

And then a second perfect match on the movement of Erik swooping down on Christine, like a bird, with his hands clasping Christine’s face. With his disfigurement revealed Erik turns sadistic, arching his face into a snarling laughter, telling her “Feats your eyes, glut your soul on my accursed ugliness!” The line reveals Erik’s double-sided sense of self-pity and irony.

Erik then pushes her away, the scene cutting yet again on action to a full two-shot. Erik again raises his arms over his head in triumph. But in triumph of what exactly? The repeated use of match on action edits serve only to underscore the gestures. His arms waving aggressively over his head are symbolic of an empty triumph, an overstatement of something desired but not achieved. Perhaps his overstated victory gesture is an expression of what Linda Williams in her detailed feminist/psychoanalytical analysis of this scene says is sign of his “sexual lack.”

Erik’s follow-up gesture of placing his hands over his face is an act of shame, shame of the woman he loves seeing his ugliness, his disfigurement, his ‘sexual lack.’ Only after a tight close-up of Christine’s face where she begins to show signs of easing up her fear, does Erik remove his hands from his face, creating a sort of second ‘unmasking,’ one of his own making. The dramatic under lighting on his face, a classic horror film lighting style, renders him pitiful rather than threatening….

Being ‘unmasked’ again

Erik reiterates the warning that she did not heed about wanting to see his face, but forgives her her transgression and allows her to “return to her world” to continue singing, while also promising to never see her again (a promise he will soon break, in fact, in the next scene). His act is one of generosity and selfless love. But his act of mercy comes with a price: he still claims her as his property and forbids her from seeing or loving any other man. As if to admit guilt again for his qualified generosity Erik hides his face in shame once again with one hand, before turning away from her and walking to lean up against a wall. Melodramatically and theatrically, he turns back to face Christine with both hands clasped over his ‘broken’ ‘damaged’ heart (another gesture of weakness, of a ‘lack,’ and a third symbolic ‘unmasking’). Seeing his pain, Christine promises to never again see her lover, a promise she too will soon easily break. The scene then fades to black.

My reading of this key scene has focused on the fine details in the editing, the physical performances in the use of body movement, and less so on the subtle play in who is doing the looking. This latter aspect has been a major component of other people’s reading of this scene, notably the cited Linda Williams, and I would now like to briefly explain this reading, which certainly can be matched up with some of my findings.

The main point that Williams makes in her essay is in the connection between the ‘monster’ and the victim, the woman, and the fact that the woman too is given the power to look suggests an affinity between them, a shared sense of being different in the eyes of patriarchy, Erik for his physical disfigurement, his ugliness, and Christine for her physical difference (her lack of a penis, to be bluntly Freudian). But Williams ties this shared difference to something more, to a sense of empowerment for the woman, or to an expression of power in the face of patriarchy: a power in the lack.

As Linda Williams argues, it is not only the monster’s penetrative gaze at the female victim that is at play, but the ‘look back’ by the victim at the monster which suggests an empathy between the victim and the monster because the victim in her look back not only admits her attempt to usurp male power but also gives evidence to a recognition “of her similar status to the monster ‘in patriarchal structures of looking’” (p. 39). The woman sees herself as being ‘different’ like the monster does (think Frankenstein’s monster, and his horror at seeing how ugly he is and how different he is from others…the monster wonders, why did my master make me so different?). Compared to the traditional silent film where the woman is not granted the pleasure of looking, this act of looking back at the monster has a subversive element, according to Williams, by giving the woman the pleasure to look. So at one level the look comes with punishment (the woman is frightened and screams in terror for her desire to look) but in the affinity with the monster, there is the acknowledgment of a shared strength, since it is this very same fear of difference in the monster that makes him threatening to other male characters, and at once a figure of attraction and repulsion for female characters. Ultimately with Freud, everything comes down to sex. And part of the attraction female characters have to the Phantom (or monsters in general), and the fear that male characters have of the monster is sexual in nature. The men fear what they think is the great sexual power of the monster, while the women of course, are attracted to this same sexual power.

This idea of sexuality is transferred over to what is hidden under the mask. Williams speculates on what the female reactions to the Phantom’s facial disfigurement might imply. In the film two dancers from the ballet corps argue about the supposed Phantom’s nose. One says, “He had no nose!” and the other, “Yes he did, it was enormous.” The first expresses a ‘sexual lack,’ the second a ‘sexual strength.’

“Clearly the monster’s power is one of sexual difference from the normal male. In this difference he is remarkably like the woman in the eyes of the traumatized male: a biological freak with impossible and threatening appetites that suggest a frightening potency precisely where the normal male would perceive a lack” (p. 87). The monster can be seen as a “double for the women” (p. 87).

All of this talk of castration fear and lack of a penis assumes, of course, a patriarchal Freudian view of female sexuality, and a Laura Mulvian view of female spectatorship, where there is no real fun for women because they are passive to-be-looked-at objects and are rarely accorded the power of looking, and are ‘punished’ for the fear of castration they invoke in men, consciously or unconsciously, by either sadistic or fetishistic means. Williams brings in an alternate feminist view, one proposed by Susan Lurie in her essay “Pornography and the Dread of Women.”

Susan Lurie argues that the child’s Oedipal experience is not one where the mother is seen as being weakened by her lack of penis, but rather the recognition that his mother, while lacking the penis, is not powerless. The whole castration fear is actually a disavowal of this “unsettling discovery”, as a lie that covers up “the child’s recognition of his mother’s power in difference” (p. 39). Yes the mother is missing a penis, but she is not dead, she is not bleeding, she is not in pain, she MUST BE stronger because of it!

Williams continues, “I suggest that the monster in the horror film is feared by the normal males of such films in ways very similar to Lurie’s notion of the male child’s fear of this mother’s power-in-difference. For, looked at from the woman’s perspective, the monster is not so much lacking as he is powerful in a different way. The vampire film offers a clear example of the threat this different form of sexuality represents to the male. The vampiric act of sucking blood, sapping the life fluid of a victim so that the victim in turn becomes a vampire, is similar to the female role of milking the sperm of the male during intercourse. What the vampire seems to represent then is a sexual power whose threat lies in its difference from a phallic norm. The vampires power to make its victim resemble itself is a very real mutilation of the once human victim (teeth marks, blood loss), but the vampire itself, like the mother in Lurie’s formulation, is not perceived as mutilated, just different” (p. 89).

“Thus what is feared in the monster (whether vampire or simply a creature whose difference gives him power over others) is similar to what Lurie says is feared in the mother: not her own mutilation, but the power to mutilate and transform the vulnerable male” (p. 90).

Getting back to The Phantom of the Opera, “… in the classic horror film, the woman’s look at the monster offers at least a potentially subversive recognition of the power and potency of a non-phallic sexuality. Precisely because this look is so threatening to male power, it is violently punished” (p. 90).

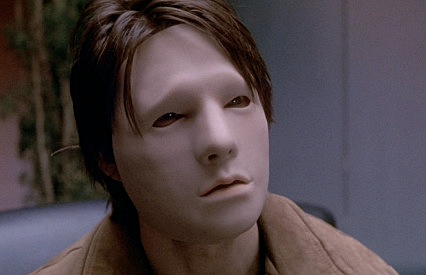

This groundbreaking scene also influenced and set the trend for dozens of later horror films to develop and expand on the dynamics of the mask, and the moment of the unmasking. The closest progeny of course are the dozens of remakes of The Phantom of the Opera, including the unusual take in the Chinese version, The Song at Midnight (1937), where it is a man, a friend of the Phantom, who does the unmasking. “This unveiling (unmasking in most accounts) of the Phantom’s disfigured face to a man rather than a female love interest marks one of the most radical twists from the American (and British) versions of the Phantom of the Opera story. The relationship between the phantom figure and another male is one of friendship rather than unrequited love.” The closest film type to emulate the unmasking moment is The Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933, Michael Curtiz) and its remake, The House of Wax (1953, Andre de Toth). In both these films the woman “unmasks” the villain inadvertently, with slaps to the face that accidently chip away the ‘normal’ face (Lionel Atwill and Vincent Price respectively) to reveal the ugly, burned face behind the ‘wax’ mask. Vincent Price’s face is used again as a surrogate mask in the “Phantom of the Opera” influenced The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971 and its sequel, Dr. Phibes Rises Again, 1972). In these two films Dr. Phibes wears a ‘mask’ in the image of the actor Price to cover-up a disfigured face he received in a car accident. One of the most harrowing unmaskings occurs in the extraordinary Georges Franju film, Les yeux sans visage (1959), where the daughter’s poetic, featureless face mask is lifted during her father’s medical intervention to graft a new face onto her disfigured one. Like in Phantom, the face appears out of focus. Reports state that people fainted at this scene during its original run. George Romero’s Bruiser (2000) is a horror version of The Mask (Chuck Russell, 1994), the live-action, part animation film starring Jim Carrey. In both films a spineless man is transformed into a fiercer or more assertive version of himself by the act of wearing a mask. In Bruiser the man, Henry Creedlow’s (Jason Flemyng) designs the mask for a party but then finds it grafted onto his face after a night’s sleep. A mask which can not be removed recalls perhaps one of the most terrifying masks in cinema history, the demon mask worn by the murderous woman in Onibaba. In Halloween, Laurie Strode momentarily ‘disempowers’ Michael by removing his mask, giving us a glance at what the real Michael Myers looks like. Tom Cruise in Vanilla Sky wears a mask similar to Myers’. And then there are other iconic masks from later, modern horror films, like Jason’s hockey mask which covers his rotting face, the Scream franchise’s Munch-like mask, Leatherface’s human flesh mask, or in another context, the Guy Fawkes mask worn throughout V for Vendetta by the anti-hero V (Hugo Weaving), and never removed. Or the eerie stunt driver’s mask worn by the Ryan Gosling character in Drive. Perhaps because it is a teasing denial of our cinematic desire to look, but the list of seminal and defining cinematic masks goes on and on….

The Mystery of the Wax Museum

House of Wax

Les yeux sans visage

The Abominable Dr. Phibes

Michael Myers in Halloween H20.

Tom Cruise in Vanilla Sky

Bruiser

Onibaba

Jason from the Friday the 13th franchise

The Scream films

Leatherface from The Texas Chainsaw Massacre

V for Vendetta

The Driver’s (Ryan Gosling) surreal doppelganger mask

But to wrap up, in this five minute scene from The Phantom of the Opera (1929) analysed closely above we can see the kernel of so much later horror film lexicon and horror film theory. Remember that at this point in film history, either 1925 or 1929, the horror genre per se had not yet been born, yet alone defined. The first time a film was specifically labeled and marketed as a horror film by a studio was 1930, with Universal’s first of many classic horror films, Dracula. Before then, films such as The Phantom of the Opera, and other Chaney vehicles, would have been referred to in the trade and press papers as ‘melodramas.’ Yet disorienting edits, lighting from below, shifting audience sympathies, issues of psycho-sexual and gender dynamics, issues of voyeurism, spectatorship complicitness in the act of gazing, the attraction and repulsion complex, and much more in a neat five minute scene somewhere in the studio-made catacombs of the Paris Opera House.

Bibliography

Carroll, Noel. The Philosophy of Horror, or, Paradoxes of the heart. New York : Routledge, 1990.

Clarens, Carlos. The Illustrated History of Horror. Capricorn Books, 1969.

Haberman, Steve. Silent Screams: Chronicles of Terror. Luminary Press, Baltimore, Maryland, 2003.

Lurie, Susan. “Pornography and the Dread of Woman,” Take Back the Night, ed. Laura Lederer (New York: William Morrow, 1980), pp. 159-173.

Sklar, David. The Monster Show: a cultural history of horror. New York: Norton, 1993.

Williams, Linda. “When the Woman Looks,” in Re Vision: Essays in Feminist Film Criticism, eds. Mary Ann Doane, Patricia Mellencamp, and Linda Williams (American Film Institute monograph series, Los Angeles, 1984), 83-99.