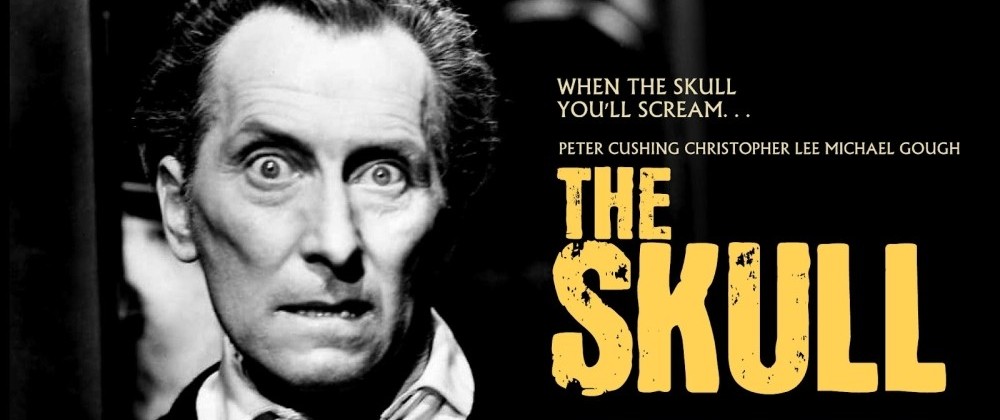

The Skull: A Study in Point of View

A long time sought after title for horror fans finally arrives on DVD thanks to the relatively new (since 2001) DVD label Legend Films. And it is a good thing that The Skull (which is one of Freddie Francis’ two or three strongest films as a director) finally makes its video debut in a format which embraces proper aspect ratio rather than the glory days of video, where full screen pan and scan and cropped formats were the norm for widescreen films. The reason for this is that a large part of The Skull??’s interest and effectiveness comes in its use of the full 2.35 techniscope framing. Throughout its sparse 83 minute running time former director of photography Freddie Francis serves up some striking compositions and framings which place much of the important information of the mise en scène on the peripheral of the frame. Although ??The Skull is a popular film intended for mainstreams audiences, it shows great respect for its audience by playing things subtly, and leaving it up to viewers to scan the usually busy frame for relevant objects or atmospheric touches which, in the context of recent horror films that are pitched at a histrionic level, makes for a much more involving experience.

A great deal of this ‘involvement’ derives from the film’s use of subjectivity and point of view. The film (based on the short story “The Skull of the Marquis de Sade” by Robert Bloch) recounts the story of a skull purportedly belonging to the great French writer/sadist Marquis de Sade which, according to legend, is haunted by an evil spirit. According to one scholar the theory is that the Marquis was not mad, but possessed to do the sadistic acts he perpetrated by an evil demonic spirit which he summoned through black arts rituals. The spirit did not die with the Marquis, but was transported into the Marquis’ skull. This is dramatized in the film’s opening prologue, set in France shortly after the death of the Marquis (1812); a man in a wonderfully gothic looking studio cemetery breaks into a coffin and decapitates a corpse and then takes the head back to his laboratory. We later learn that the grave robber is a phrenologist trying to prove whether or not the Marquis was insane by studying his brain. The doctor cleans the skull in a vat of acid. In the next scene his lover finds him in his laboratory dead, with his throat slashed.

We cut to the present day England, and are introduced to two well-to-do men at an auction selling odd historical artifacts, Sir Matthew Phillips (Christopher Lee) Dr. Christopher Maitland (Peter Cushing). Both men are known collectors of the weird and esoteric. In the auction Phillips vastly overbids on a series of four demonic statuettes.

Later that night Maitland receives a visit by a regular acquaintance who supplies him with a steady stream of said artifacts, Anthony Marko (Patrick Wymark). The cool reception he receives from Maitland’s wife Jane (Jill Bennett) lets us know that he is a shady character. Marko tempts him with a peculiar item: a book written by the Marquis de Sade made a curio item by the fact that its cover is made of human skin. Maitland purchases the book for 200 pounds, but the conniving Marko is using this occasion to bait Maitland into buying another prized object, the skull of the Marquis himself. Marko’s explanation of the skull’s authenticity is relayed in a flashback where Pierre’s (Maurice Good) executor is possessed by the skull into killing Pierre’s lover, introduced in Pierre’s opening death scene. This also marks the first instance of the by now famous ‘skull’s point of view’ shot (lit in a sickly green light), where the camera peers out through the vacant eye sockets, the first of many such “impossible” camera angles (other such shots include the camera looking out from a coffin, a fireplace, the broken glass of a cabinet, etc.).

The effect is more than just a neat visual trick but a literal metaphor for how the skull figuratively gets into people’s heads. When Maitland asks Marko how he came to possess (pun intended) the skull, Marko’s answer implies that such moral and ethical questions were never an issue in the past when it came to him procuring his ‘research materials’. This sets up a standard moral dilemma faced by many celluloid scientists (starting from Dr. Frankenstein, which is alluded to also by the film’s grave robbing opening) which will grow heavy on Maitland as the film develops and he begins to question his own values and ideals as a ‘scholar.’ Rather than having this moral dilemma spelled out or stated through a line, director Francis alludes to it in a moment of sheer visual brilliance that is largely lifted from Franz Kafka’s story The Trail, and its film version from 1963, by Orson Welles.

Over a game of billiards Phillips tells Maitland that Marko stole the skull from him, but he was quite happy to see it leave because he felt its demonic powers taking hold over him. He admits that he was under the skull’s persuasion the day of the auction, which explains his odd behaviour and the reckless manner in which he overbid for the set of cursed relics, one of which is later stolen by the possessed Maitland to use in a black arts ritual. Phillips recounts his interpretation of the Marquis de Sade, and how he was not mad but possessed by an evil spirit which still resides in the skull (it is unclear whether the evil spirit took over the Marquis’s body or originated with him).

Later that night Maitland is home reading his newly bought book by the Marquis. Director Francis enlivens the static action by cutting to various angles and shot distances of Maitland. In one cut we hear a knock on the door. Maitland answers the door and is confronted by two fedora wearing, noir style detectives who abruptly arrest him, without stating a reason. Although the appearance of the two detectives is disarming, the scene still appears realistic. Subtle touches such as the shift to heightened sound and extreme close ups of Maitland begin to edge the scene away from reality. Maitland is summoned into a sparse, all-blue room to meet with a sullen-faced judge, who forces Maitland into a game of Russian roulette. By now things are wholly surreal and get worse when he is locked into an all red corridor, where fumes begin to leak out of the vents, the skull begins to float toward him, and the walls slowly move in toward him. By now we realize that this is a dream spurred on by his sense of guilt over his past inequities with Marko, a “dream of conscience.” As the skull floats toward him he covers his face with his hands, yells, at which point the shot cuts to Maitland in the same position, but in a different location, seemingly awaking from his nightmare. What appears normal turns strange once again as he walks around his new location only to discover he is in Marko’s building, and then walks back home.

If the previous sequence was a dream, then how did he get to Marko’s place? Did he sleepwalk? This is an intriguing possibility because it would be one of several references to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. In a scene described below Maitland is compelled by the skull’s demonic power to sneak into his wife’s bedroom with a knife and attempt to kill her, a scene which finds its literal echo in the classic Weine film from 1919 (see photos below). In an essay on Francis’ The Creeping Flesh I note how the film’s framing device structure –which reveals the events as the crazed imaginings of a patient in an insane asylum– was lifted from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. All of this simply to note that The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari seems to have been an important reference point for Freddie Francis.

Even with this warning in the shape of a dream, Maitland ventures over to Marko’s flat to buy the skull. Once there he discovers Marko’s corpse behind a door and secrets the skull before calling the police so he can return later to claim it (one of the two officers is played by Patrick McGee, who would star in many later Amicus Omnibus films). A tussle with the tenements janitor leads to his accidental death as he falls over the railings. Unperturbed, Maitland returns to his home and places the skull inside a glass cabinet, as if it were a prized trophy. This leads to another symbolic image of the skull shot through the cabinet’s glass door with Maitland’s reflection seen in the glass. By framing Maitland and the skull together the image foreshadows the one-on-one battle that will surprisingly take up the rest of the film. By making one part of the ‘two shot’ an ‘immaterial’ reflection the effect also suggests an internal battle between Maitland and his own conscience, or guilt.

What is most striking about the film’s concluding twenty plus minutes is that it is played without dialogue (except for a moment where Maitland yells for his wife’s help), a tour de force of physical acting on Cushing’s part, aided by moving camera, subjective point of view and pulsating/flickering lighting effects. The sparse, almost experimental nature of this film’s final twenty plus minutes only serves to underscore the subjective, ‘internal’ nature of Maitland’s battle. The black background of the cabinet sets off the nearly white skull, as if to heighten its presence inside Maitland’s psyche. The skull begins to move on its own, floating across the room and landing itself on a round table, followed by the Marquis book, which hovers off the library shelf onto the table. The skull rests on a pentagon, signaling the presence of the black arts. The film shifts from subjective POV shots of Maitland moving forward with a knife in his hands, to the iconic skull’s POV, as if to cement the notion that the skull is inside his head. His mind now controlled by the skull, he sneaks into his wife’s bedroom and stands above her sleeping body, holding the knife menacingly above his head, a shot which is as much an homage to The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, where the hypnotized Cesare sleepwalks into a woman’s bedroom brandishing a knife, as to classic Hammer vampire imagery (his wife’s life is saved by a cross hanging around her neck resting on her exposed bosom).

In tune with the classic Hammer morality tale, whatever evil resides within Maitland is momentarily defeated by the symbolic powers of Christian good. In a wonderful bit of subtle mise en scène, Maitland moves away from the bed and rests his back up against the wall; to his immediate right the observant viewer will catch a skull-like formation on the pattern of the wallpaper –another reflection of the skull’s omnipotent power.

With all of these clever touches one almost wishes that Francis would have made the premise a bit more ambiguous regarding the nature of the killings, by leaving open the possibility that the mind control was psychological rather than supernatural (at least in the case of Maitland). But any such reading would be hard pressed to account for all the touches of the irrational and unnatural. Maitland is pursued by the skull, its presence suggested with pulsating light, constant camera movement and a magically moving hot spot of light. He stabs the skull in the eye, but the knife reappears impaled in his pillow (another suggestion of how his head is being ‘punctured’). A large hourglass attached to the wall magically turns itself over to start a countdown, as if the skull were stating that Maitland’s time is running out. Maitland is now at his most hysterical, locked in a room, frenetic hand-held camera pinning him up against the walls as he yells out, ‘Jane, help me.” The gravity defying skull floats toward him from across the room. The scene ends echoing the opening prologue, with his wife Jane finding Maitland’s dead body lying across his bed, his throat slashed, and the skull at the foot of the bed. The same two police officers investigate the scene of the crime and note the parallel to Marko’s death, but dismiss any possibility of witchcraft or the supernatural.

This Legend Films DVD is in remarkable shape for a film of over forty years. The colors are vibrant and the image is crisp, yet not to the point of obliterating natural film grain, bringing out the wealth of detail in the film’s art direction and rich production design (rooms are littered with masks, statues, paintings, bric-a-bracs, etc.). The DVD is a bare bones presentation, with only a slightly tattered 1:85 trailer, but the film itself, so well preserved in its proper 2.35 anamorphic and enhanced for widescreen TV, is reason enough to rejoice, and I seriously doubt any other label will top this presentation of the film. Table this in as the definitive version of the long awaited The Skull.

The Skull (1965)

Dir. Freddie Francis

Producers; Max Rosenberg, Milton Subotsky

Writers: Robert Bloch story The skull of the Marquis de Sade adapted by Milton Subotsky

DP: John Wilcox

Music: Elisabeth Lutyens

Editing: Oswald Hafenrichter

Cast: Peter Cushing (Dr. Christopher Maitland), Christopher L (Sir Matthew Phillips), Patrick Wymark (Anthony Marco), Jill Bennett (Jane Maitland), Nigel Green (Inspector Wilson), Patrick Magee (Police Surgeon), Peter Woodthorpe (Bert Travers, Marco’s Landlord, Michael Gough (Auctioneer), George Coulouris (Dr. Londe)