The Idea and the World As It Is: Catholicism and Insanity in El and Nazarin

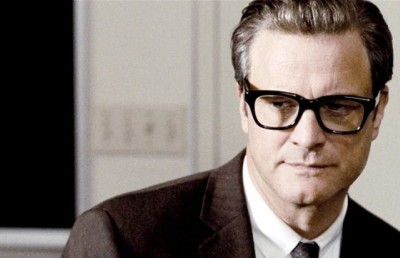

In his films El (1953) and Nazarin (1959), Luis Buñuel offers a barbed critique of Catholicism through portraits of two characters whose attempts to live by Christian ideals can be seen as forms of madness, the disastrous result of taking the teachings of the Church seriously and carrying them through to their logical conclusions. This critique focuses on the role of the Church as a pillar of authoritarian government which survives through oppression, particularly of the poor; the perverse results that the severe oppression of sexual behaviour has on relations between people; and the ineffectuality and irresponsible naiveté of Christian ideals. In El , Francisco Galvan (Arturo de Córdova) is the ideal of the Catholic layman and is described by his priest as “a perfect example for others,” while in Nazarin , Father Nazario (Francisco Rabal) is an idealistic priest who patterns his life on a literal interpretation of the teachings of Jesus Christ. Buñuel uses these exemplars to explore the “abyss that can exist between an idea of the world and the world as it is” (de la Colina 152), depicting the Roman Catholic idea of the world as one which is cut off from the practicalities of everyday life, where the films’ “ideal” Christians rarely understand what they are told and, in turn, are constantly misunderstood by the people they are speaking to.

Buñuel was raised and educated in an atmosphere where, he writes, “religion permeated all aspects of our daily lives” (Buñuel 12), and Francisco Aranda makes the point that the particularly backward nature of the Spanish Catholicism that permeated Buñuel’s youth meant that his anti-clericalism was not simply “intellectual and rational,” but one that saw religion as an “anxious preoccupation from which he liberated himself by reacting violently against it” (Aranda 16-17). The violence of this reaction is reflected not only in El and Nazarin , but in aspects of several of his other films that also equate religion with madness, oppression or misguided charity. But the permanent effect of this intense early involvement with Catholicism can be seen not only in his attacks on the Church, but also in ambiguities that, in some films, signal a less than total rejection of religion.

The Roman Catholic Church is often linked with oppressive civil authorities in Buñuel’s films, most notably in The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz (1955), where at the wedding ceremony the camera frames a priest, a soldier and a judge having a conversation, and Buñuel sardonically has them lavish praise on each other. Similarly, in Nazarin we see a soldier, a priest and a woman of property who, while delayed on the road, bully a peasant who is walking by. Buñuel sees the Church’s role as a necessary agent of both political and psychological oppression, since “in a rigidly hierarchical society, sex – which obeys no barriers and respects no laws – can at any moment become an agent of chaos” (Buñuel 14). In a scene from El , which in its staging is very similar to the one mentioned from The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz, representatives of two pillars of Catholic society, the Church (Francisco’s priest) and the Family (Francisco’s mother-in-law) discuss what a “perfect gentleman” Francisco is. These are also the people Francisco’s wife Gloria (Delia Garcés) turns to after she is beaten, only to be told by them that this and other signs of Francisco’s madness are normal. Buñuel seems to go out of his way to have characters approve of Francisco, and Ernesto Acevedo-Muñoz notes that he is “commended for his righteous ways by his priest, his valet, his male friends, and even his mother-in-law” (Acevedo- Muñoz 133). But if Francisco’s pathological behaviour is “normal” and he is, as Buñuel describes him, “authentically Catholic” and a man who “adheres to society’s rules” (de la Colina 97), then Buñuel is making a savage commentary on Catholic society.

Throughout El , Francisco is linked to the priesthood. He is introduced taking part in a Church ceremony, is celibate before his marriage, has an estate whose heavy wooden gates resemble the doors to a cathedral, sleeps with a large stand-up crucifix beside his bed and has a house whose art deco design echoes the baroque character of his church (the top of its staircase in particular resembling the high altar). The wedding ceremony is held at Francisco’s home rather than at the church both he and Gloria attend, reinforcing the idea of his house being sacred ground. When Francisco asks Gloria for details of her sexual history, he says “tell me as your confessor,” that is, her priest. So when Francisco calmly and deliberately lays out the razor, needle and thread he intends to use to ensure Gloria will never be unfaithful to him (by sewing up her vagina), it is impossible not to be reminded of a priest preparing Communion. It may even seem rational to him to perform the same role of agent of sexual repression in his marriage as the Church had in his life.

For Francisco’s life is thoroughly oppressed. Buñuel uses a mise-en-scène of enclosed spaces and darkness to portray Francisco’s world, setting scenes in a dark church, an over-furnished house and a tiny train compartment. At the Holy Thursday Mass in which Francisco assists at the beginning of the film, Tony Richardson notes the focus on “the heavy, oppressively ornamented setting, the strain on the blanched faces of the boys, the weary ritual” (Aranda 161). The parishioners crowd closely and press against the rail, the men in dark suits, the women wearing dark dresses and black lace veils, and they seem to melt into a grey-black amorphous mass, almost blending with the dim shadows. When Francisco first talks to Gloria, they are framed tightly in a two shot as they huddle in a corner of the church. By contrast, when she meets her fiancé Raul, it is in a brightly lit restaurant and later in an open street. When Gloria finds the marriage becoming increasingly nightmarish, she describes the feeling as one where “the walls seemed to have low ceilings.”

The form this oppression takes is, of course, sexual. Mathew Viola argues that Francisco’s “deeply ingrained sexual neuroses,” in particular his “Madonna-whore complex,” are “firmly rooted in the repressive practices of the Church.” (Viola) The Buñuelian identification of Catholicism with sexual repression goes back as far as Un Chien Andalou (1929), where a sexually aroused man trying to reach a woman is hampered by having to drag two priests (along with a piano and various other objects) behind him, and can be found in most of his work. The roots of this go back to Buñuel’s religious upbringing, where he recalls that “despite our sincere religious faith, nothing could assuage . . . our erotic obsessions,” and the “interminable war between instinct and virtue” left him “worn out with an oppressive sense of sin” (Buñuel 14). That Francisco’s obsessions are tied to his Catholicism is evident in Buñuel closely following the extended eroticized close-up of the priest kissing an altar boy’s foot during the washing of the feet ceremony, which Peter Harcourt describes as being “tinged with repressed sexuality” (Harcourt 5), with Francisco’s sudden attraction to Gloria after seeing the apparently inviting set of her feet. Ed Gonzalez writes that “Buñuel is very much concerned with calling attention to the poisonous wisdom of supposedly celibate clerics advising man to suppress human desire,” and that in the case of Francisco’s madness, “the only person to blame here is a church that has made him into a pervert” (Gonzalez). Buñuel himself writes that “sexual desire has to be seen as the product of centuries of repressive and emasculating Catholicism” that has “turned normal desire into something exceptionally violent” (Buñuel 48). So it is no accident that when Francisco loses total control, Buñuel has him unconsciously strike at the source of his agonies by attacking and throttling his priest as he is saying Mass.

There are two places in Francisco’s world where he is free of repression. The first is in his house’s wild garden which, like the garden in L’Age d’or (1930) or the tropical garden of the dream sequence in Ascent to Heaven (1952), has sexual associations. It is here, for example, where Francisco first kisses Gloria. But it is no peaceful haven, since being told that Gloria has gone into the garden with his lawyer makes Francisco violently jealous. The only genuinely peaceful place he has found is a church’s bell tower, which he describes as “high, free from my worries.” Buñuel has already shown that Francisco likes to look down on people from great heights. Standing with Gloria on a hill overlooking his hometown, he says the view from this distance “makes things look pure and clean” and he later has Gloria take his picture from the bottom of an enormous staircase (of a church, naturally) as he stands alone at the top. His preference for being photographed alone also seems significant, as the only time he takes Gloria up to his prized bell tower (in a scene Hitchcock must have seen before making Vertigo [1958]), he tries to throw her off of it. This desire to be detached from humanity and superior to it, free of his (and the world’s) sexual obsessions is not far removed from the asceticism of Nazarin ’s Father Nazario, who makes no distinction between his love for his “disciples” Beatriz and Andara and his love for a snail he has picked up from the ground (and is stroking, perhaps a sign of unconscious eroticism). This is echoed even more strongly in Simon of the Desert (1965), which also features an “almost priest” who likes to look down on sinful humanity from a great height and makes no distinction between men and animals (as when he insists on blessing both the dwarf and the ram at the same time). Francisco may look down and want to crush everybody like worms instead of blessing them, but the important thing is that, like Nazario and Simon (and the title character in Virdiana (1961)), he wants no genuine emotional involvement with the people “below” him. Following from this, Francisco’s fate can be seen, like much of the rest of the film, as a dark joke. He finds peace of a sort in a highly repressed environment, a monastery where there are no women and he is enveloped in a monk’s habit and a cowl that usually hides most of his face. That he is still crazy is shown by his remark about Gloria (“maybe I wasn’t as mixed up as they said”) and by his zigzag walk, but nobody notices. Given Buñuel’s association of religionwith madness in El , the Abbott’s comment that Francisco has fit into the religious community perfectly can be taken in more than one way.

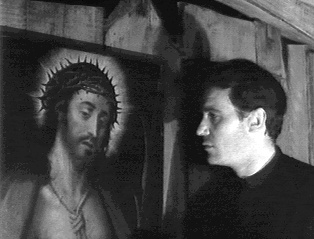

If in El Buñuel examines the Catholic Church as an institution, painting it as an agency of oppression, in Nazarin he examines Catholicism as a religion and paints it as absurd and impractical. Buñuel was once asked by a Dominican priest how he could consider Christ an “idiot” when he said “Love thy neighbour as thyself.” His answer was “Give me a ball-pen, and in fifteen minutes I’ll write ten sentences like that. What’s the use?” (Aranda 213) Buñuel has no use for the maxims of Christianity because they seem to have little relation to the world that he sees around him, and in Father Nazario he has a “hero” who has decided to live by these unrealistic maxims, an “exceptional priest who wants to live in agreement with the spirit and letter of original Christianity” (de la Colinda 133). Buñuel considers him “a Quixote of the priesthood; instead of following the example found in tales of knighthood, he follows the Gospels” (de la Colinda 132).

In several of his films, Buñuel mocks Christian ideals, particularly the idea of charity, which he considered both ineffectual and counterproductive. This ineffectuality was best illustrated in Viridiana, where Jorge (Francisco Rabal, again) buys a dog to rescue it from being forced to trot behind a horse cart it is tied to, only to have another horse cart with a dog tied to it roll by in the other direction a moment later. The counter-productiveness of charity takes two forms. First, it legitimizes oppressive systems. As Buñuel says, “if, in bourgeois society, there is an understanding teacher who helps mentally retarded or delinquent children, this does not justify monstrosities of social injustice” (de la Colina 60). But the second form is more drastic, it “produces catastrophes” (de la Colina 152). In Buñuel’s films, charitable impulses where there is no real connection between patron and receiver almost always end in disaster. In Los Olvidados (1950), for example, the farm director tries to help Pedro out of kindly paternalism. When asked what the consequences will be if his social experiment fails, he shrugs and says he will “be out 50 pesos.” Instead, his action leads almost directly to Pedro’s death. In Viridiana, the beggars ransack the house, rape (or possibly only attempt to rape) their benefactress Viridiana, and end up either dead, having killed for money, on the run or carted off to jail.

Similarly disastrous consequences of charity run through Nazarin , which, as Aranda argues, is a film about “the failure of a purely Christian attitude in a world as imperfect as ours” (Aranda 177). Nazario tries to live in the steps of Christ, not caring about material goods or his dignity, and rejecting pleasures of the flesh. In return, he is repeatedly robbed, cheated, slandered, misunderstood, humiliated and beaten. Wherever he goes, his attempts to live a true Christian life leave a path of destruction. He gets the usually realistic landlady to turn a blind eye when he hides Andara, and in return her inn is burned down. He offers to work in return for food because he doesn’t care about money, and this sparks off a savage brawl between workers and the local boss which ends in the off screen sound of gunfire. In the plague village, his attempts to get a dying woman to think about Heaven are rejected as she instead opts for her earthly love, saying “Cielo no, Juan si,” and Nazario and his helpers are forced to leave the house. As Buñuel says, “whenever Nazario gets involved, even in the best of faith, he only begets conflicts and disasters” (de la Colinda 134). His one “success,” the revival of a sick child, is a thorough mockery of his ideals, as the wailing and hysterical women who hail his “miracle” follow a superstitious religion far more akin to paganism than his high minded Christianity.

Unlike Francisco, Father Nazario is not linked to the Church as an institution. Only once is he shown in a church, and that is while changing in a sacristy. He is never shown offering Mass or administering a sacrament. He admits he has “rarely stood in a pulpit” and rejects the material goods the worldly priests he encounters (and Francisco) consider their natural right. But like Francisco up his bell tower (or Simon on his pedestal), Nazario believes detachment from his fellow men, which he hopes to achieve during his pilgrimage to the countryside, will bring him “closer to God.” But, as Harcourt points out, “he rejects the world of the flesh with such insistent thoroughness that he is unable to know what it is all about. So he is useless to everyone” (Harcourt 14). Closer to God, as Buñuel sees it, means more useless to Man.

Another characteristic shared by Francisco and Nazario, and, by implication, the Church and religion they represent, is an almost complete breakdown of communication between themselves and the world around them. Despite increasingly obvious symptoms of madness, nobody except Gloria notices anything wrong until Francisco attacks the priest. Francisco, in return, fires lawyers and maids who tell him things he doesn’t want to hear and hears things people never actually tell him. This is shown at one point when he states that his second lawyer told him his lawsuit will be won within weeks, and the surprised man later tells Gloria he never said anything like that. Its most extreme manifestation is when he believes all the people in the church are laughing at him. Similarly, Nazario is twice shown preaching to his “disciples,” Beatriz and Andara. The first time, they respond by talking about demons and evil eyes, showing they have no idea what he was talking about. The second time, they ignore him. He, in turn, has no clue that their passion for him is far more carnal than it is spiritual.

Buñuel contrasts Nazario’s uselessness and obliviousness with genuine acts of useful compassion. When the sick woman’s lover, Juan, arrives at the plague house, he kisses her and gives her the kind of comfort she needed, something more personal than what she was getting from Nazario. Octavio Paz writes that in this scene, “the supernatural gives way to something marvelous: human nature and its powers” (Aranda 180). Another contrast is offered in the character of the dwarf, Hugo. Unlike Nazario, he sees Andara as she is, but offers love anyway. He also offers practical help to the child forced to march with the prisoners, comforting her and giving her a piece of fruit. Hugo may be profane, ugly and ignorant, but he is, as Harcourt writes, “the most affirmative figure in all of Buñuel, the most complete incarnation of . . . Christian love” (Harcourt 13). That he ends heartbroken and collapsed in the dirt may be sad, but there is no sense that he is in any way surprised by his fate. Unlike Nazario, he sees the world as it is, and at least in this character Buñuel allows for the possibility of a type of Christian behaviour that is not disastrous.

This ambiguous desire to stop short of completely rejecting religion is also shown in Nazario’s possible redemption. Unlike Francisco, who remains mad and never comes to a realistic view of the world, Nazario has a moment of clarity when the “good thief” among his fellow prisoners tells him: “You are on the good side and I am on the bad. Neither of us serve any purpose.” He realizes that his principles of faith and morality have collapsed disastrously around him and that his attempt to live the Christian ideal was really obsessive self absorption. When his Church superior calls him “mad,” he can only hang his head and remain silent. Buñuel says that “Nazarin and Viridiana also change their way of seeing and living in the world. They can no longer remain as they were before” (de la Colinda 124). But Buñuel is ambiguous about how Nazario will live in the future. It depends on how the final scene where Nazario is offered a pineapple by a peddler, refuses it, and then accepts it, is interpreted. Buñuel has said “I don’t try to show that Nazarin has regained his faith in religion or that he has completely lost his faith . . . What will happen to this man after so many experiences? I don’t know” (de la Colinda 135).

Still, it is possible to suggest that he rejects the pineapple at first because the offer reminds him of the useless charity he practiced before his disillusionment, and he finally accepts because he recognizes it as an act of practical compassion of the sort offered earlier by Juan and Hugo, which he was too blinded by his religious ideals to notice. Although he accepted charity before, it was just another way to raise himself above others by ostentatiously imitating Christ. Taking the pineapple can be seen as acceptance of himself as human rather than divine, and therefore capable of making the kind of connection that can make charity honest and useful. While this may not have much to do with Catholicism as an institution or an ideal, Buñuel at least seems to allow the possibility that it could exist in Catholics (and others) who are able to see the world around them as it really is.

Works Cited

Acevedo-Muñoz, Ernesto R. Buñuel and Mexico: The Crisis of National Cinema. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2003.

Aranda, Francisco. Luis Buñuel: A Critical Biography. London, UK: Seeker & Warburg, 1975.

Buñuel, Luis. My Last Sigh. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984.

de la Colina, José, and Tomas Perez Turrent. Objects of Desire: Conversations with Luis Buñuel. New York, NY: Marsilio, 1992.

Gonzalez, Ed. “El” Slant. (May 2, 2001)

Harcourt, Peter. “Luis Buñuel: Spaniard and Surrealist.” Film Quarterly 20.3 (Spring 1967): 2-19.

Viola, Mathew. “El .” Notes of a Film Fanatic. (June 29, 2008)