Singapore Sling: Postmodern Noir, Narrative, and Destructive Desire

Cult Cinema Extraordinaire

1.

Rain pours down through the lush foliage of an isolated villa’s backyard garden, drumming upon the roof of a nearby car. A detective sits in a puddle against the side of the car, a bottle in his hand and blood running down his wrist from a gunshot in his shoulder (the origin of which we never learn). Homeless and friendless, he has searched in vain for his lost love—a young woman named Laura—for three years, but now has a hunch that she is dead and he remains “in love with a corpse.” We soon come to know this derelict of a man as “Singapore Sling,” and he reacts with exhausted resignation at the sight of two mud-soaked, lingerie-bound women digging a deep hole in the back of the garden. Their strange actions “would have stirred me once,” he sighs, “but with a bullet in one’s shoulder one can’t do much.” Exactly how he would have been stirred—whether to investigate, to flee, to become aroused, or otherwise—remains for us to ascertain.

2.

Singapore Sling (1990), the fifth film by Greek director Nikos Nikolaidis, begins with its eponymous detective protagonist (Panos Thanassoulis) sitting outside the villa he has been investigating for some time. Later in the film we learn that he has drawn out a floor plan of the house in his notebook, along with a series of questions about Laura, the mysterious woman he is trying to track down. Delirious from drunkenness and loss of blood, the detective eventually collapses upon the doorstep of the villa, becoming captured and tortured by the two women from the garden, a pair of sadomasochists known only as Mother (Michele Valley) and Daughter (Meredyth Herold), who had been at work burying alive their recently disemboweled chauffeur.

The film immediately presents us with a number of tropes that directly reference film noir, both as a genre and a visual style. Aris Stavrou’s black & white cinematography beautifully replicates the high-contrast, sharply angular, shadow-drenched look of classical noir films. The diegetic time period itself is somewhat indistinct, but appears to be sometime in the 1940s. The trenchcoat-clad detective opens the film with his hardboiled voice-over narration, setting himself up as a morally ambiguous character within a claustrophobic atmosphere of foreboding, masochistically wallowing in despondency. Deeply flawed by the legacy of a past crime/lost love (in addition to his alcoholism), his sense of identity has become subordinate to his quest to either find Laura or discover her murderer. In classic noir fashion, his striving for sexual and ontological knowledge soon subjects him to the sadistic machinations of the two femmes fatales, but he finally emerges at film’s end with his sexual and self-identity reformed and the women severely punished for their transgressions.

3.

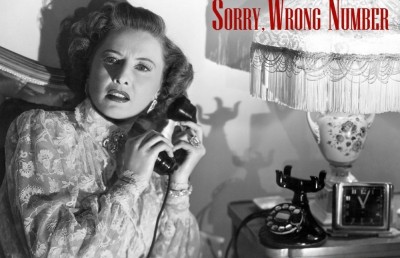

Singapore Sling most directly invokes its roots in the film noir tradition through repeated references to Otto Preminger’s 1944 noir Laura, in which Detective Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews) investigates the apparent murder of a beautiful young woman named Laura (Gene Tierney), only to become infatuated with her through her portrait and the fond recollections of the two men who loved her—both of whom have become suspects in the case. Midway through the film, Laura reappears like a ghost, having spent several days at a lake house to think over her plan to leave erudite art critic Waldo Lydecker (Clifton Webb) and instead marry man-of-leisure Shelby Carpenter (Vincent Price). Detective McPherson must keep his desire for Laura in check while investigating the identity of the woman who was actually murdered (via a disfiguring shotgun blast to the face). Laura and Shelby play McPherson off one another in attempts to protect each other, but Laura eventually begins to fall for the detective. Eventually it is learned that a murderously jealous Lydecker had pulled the trigger, mistakenly killing Diane Redfern (a close friend of Shelby’s) while attempting to kill Laura to prevent her from marrying Shelby (on whom he tries to pin the crime). Lydecker creeps back into Laura’s apartment to finish the job, only to be shot by the police as McPherson realizes his error and rushes back inside.

From Preminger’s film, Singapore Sling borrows the premise of a desirous detective investigating a dead woman named Laura who, as we shall see, seemingly reappears and begins manipulating him. A large portrait of the Daughter, posed like Laura from the film of the same name, adds to Singapore Sling’s confusion as he mistakes the Daughter for his long-lost love. Various scraps of dialogue from Laura become part of Singapore Sling, from references to the lake house and a broken record player, to Laura’s wish to contact her friends and let them know that she is still alive, to Singapore Sling’s willingness to pin a different woman’s murder on anyone but Laura (as Shelby had attempted in Laura), to a scene in which the Mother interrogates the Daughter under a lamp (as McPherson did to Laura). Composer David Raksin’s famous theme from Laura also becomes a dominant musical motif in the score to Singapore Sling. The former film becomes virtually inseparable from the latter, spurring a variety of intriguing cross-comparisons and intertextual sources of viewing pleasure.

4.

This intertextuality fits Eco’s (1985) description of postmodern cult movies arising “where the quotation of the topos is recognized as the only way to cope with the burden of our encyclopedic filmic competence” (p. 11). Cult films such as this often depend upon intertextuality for their “cultish” qualities, deriving multiple sources of potential viewing pleasure from their often uncredited relation to preexisting films. This works in conjunction with Singapore Sling??’s nostalgic and ahistorical revivalism, playing upon the sort of “mass camp” qualities that Naremore (1998) sees in the contemporary reception of classical films noirs like ??Laura (p. 261-62). While this should seemingly position Singapore Sling as a key example of the postmodern “neo-noir” film, it has received virtually no scholarly attention in this regard. Published filmographies (e.g., see Schwartz, 2005 and Spicer, 2002) of the noir/neo-noir genre regularly omit mention of Singapore Sling while nevertheless including numerous recent films with much less obvious noir influence. The limited availability (read: bootlegs) of the film until its American Synapse Films DVD release in 2006 may be one major factor in this neglect, as could its status as a film from a country (Greece) not normally associated with film noir production (unlike the United States, France, and Britain).

Singapore Sling received mixed reviews upon its release, with some critics hailing it as a disturbing cult gem like Eraserhead (David Lynch, 1976) and Thundercrack! (Curt McDowell, 1975), while others derided it as pretentious, confusing, disgusting, and misogynistic. The film’s transgressive content was apparently offensive enough to convince most critics that its unconventional narrative was altogether dismissible as too perplexing to be picked apart or taken seriously. Screened in film festivals around the world, it was nevertheless awarded prizes at the 1990 Thessaloniki Film Festival for Best Film Direction, Best Cinematography, Best Actress (Meredyth Herold), Best Art Direction, and Best Film Editing.

With its emphasis on perverse sexuality, sadomasochistic violence, and abundant bodily fluids within a glossy, noir-inspired atmosphere and a convoluted narrative, the film is a strange mix of high and low culture: artistic and self-conscious, yet shocking and exploitative. (It should of course be kept in mind that many classical films noirs were impoverished B-movies not much higher than the level of exploitation.) Perhaps this spirited combination of forces has caused the film to be dismissed from “serious” academic consideration (as it was by many critics), despite its obvious noir pedigree and indebtedness to Preminger’s Laura. However, I would argue that Singapore Sling is deserving of attention as a sophisticated revisioning of the genre precisely because it blatantly crystallizes many of the more exploitative (i.e., violent, perverse, misogynistic) and narratologically convoluted elements that already persisted (either consciously or unconsciously) within classical films noirs.

5.

Spicer (2002) has divided the neo-noir film into two categories or periods: the modernist neo-noir (1959-1981) and the postmodern neo-noir (1981-present). While this sort of periodizing always depends to some extent upon overgeneralizations, it roughly corresponds with certain well-documented historical shifts. The modernist neo-noir developed during what Jameson (1983) describes as the post-war emergence of late capitalism (p. 113), while the postmodern neo-noir began during the global popularization of postmodern theory in the late 1970s and early 1980s. This might suggest that many so-called “postmodern neo-noirs” may not be quite so different from their modernist predecessors, only having gained a new discursive label to reflect the academy’s shift away from modernism. While pastiche has certainly become more prevalent since the postmodern turn, other traits of postmodern neo-noirs can be seen as merely intensified versions of qualities already at work in modernist neo-noirs, as Spicer’s rather porous distinction between the two categories makes clear.

He argues that modernist neo-noirs are primarily concerned with “problems of identity and memory, depicting unmotivated characters adrift in ambiguous situations beyond their comprehension which they are incapable of resolving” (p. 133)—though I would argue that most of these same traits are endemic to classical films noirs as well. Spicer (2002) continues that modernist neo-noirs are also formally self-reflexive, often employing Brechtian distanciation devices (p. 133), parodically emphasizing the conventions of classical noirs in order to “demonstrate their inevitable dissolution, leading to an ambivalence about narrative itself as a meaningful activity. The misplaced erotic instincts, alienation, and fragmented identity that characterized the classical noir hero are incorporated into a more extreme epistemological confusion, expressed through violence which is shown as both pointless and absurd” (p. 136), making rogue cops the typical protagonists (p. 142). As a result, their narratives are more unmotivated, episodic, and circular than those of classical noirs (p. 148). These films are also said to display “what Frederic Jameson has described as the ‘great modernist thematics of alienation, anomie, solitude, social fragmentation, and isolation’” (p. 134). In contrast, postmodern neo-noirs allegedly engage in both revivalism and hybridization with other genres (p. 150). “The paranoia, alienation, existential fatalism, and Freudian psychopathology that were the core themes of classical noir have been retained but intensified” to the point of excess, says Spicer (p. 157). Postmodern noir narratives are even more circular and unreliable than classical or modernist noirs, often using flashbacks in a “more visceral, oblique, and ambiguous” manner (p. 158).

What emerges from Spicer’s (2002) discussion is less a clear definition between classical, modernist, and postmodern noirs than a gradual intensification of classical noir traits (whether through modernist parody or postmodernist pastiche) throughout the development of late capitalism. As the historical context of classical noir and the studio era of Hollywood have drifted into the past, the all-too-familiar motifs of film noir have been loosed from their origins, intersecting with other influences (e.g., European art cinema narration), and have become even more of a marketable commodity, today forming a sort of “noir mediascape,” in the words of Naremore (1998, p. 255). The potentially distancing devices (such as flashbacks and voice-over narration) that were already present in classical noirs are heightened and used self-reflexively for parodic purposes in modernist neo-noirs, while postmodern neo-noirs intensify such traits to the point of excess, emptying noir tropes of their parodic potential as pastiche takes precedence. The modernist themes (e.g., alienation, paranoia, loss of identity) and narrative structures (e.g., fragmentation, unreliability, circularity) of classical noirs certainly predated any specific group of parodic “modernist neo-noirs” of the 1959-1981 period (as Naremore [1998, p. 40-95] amply explains in his discussion of modernism in classical noirs), and these themes have become even more pronounced in postmodern noir incarnations (perhaps speaking to an alienating loss of the subject/real in a hyperreal world of postmodern simulacra). Of course, modernism is one of many historical styles appropriated by postmodernism—hence Naremore’s (1998) assertion that “the circulation and transformation of noir motifs is merely an exaggerated expression of modernity itself,” indicating the interrelatedness of “various aspects of the leisure economy” (p. 257). In many postmodern neo-noirs, we might therefore find a continuance of many modernist themes and concerns, appropriated and displayed beneath a veneer of postmodern pastiche, largely emptied of meaning.

Jameson (1983) has famously claimed that parody is a distinctly modernist strategy that “capitalizes on the uniqueness of these [original] styles and seizes on their idiosyncrasies and eccentricities to produce an imitation that mocks the original” (p. 113), thus containing an element of critique. However, pastiche blankly and neutrally mimics an original form without the ulterior motive of critique, appealing to nostalgia without necessarily invoking a particular historical context (p. 114). He cites Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974) and Body Heat (Lawrence Kasdan, 1981) as examples of pastiche, though that label is telling because Spicer (2002) identifies the former film as a modernist neo-noir and the latter as a postmodern neo-noir—which, I would argue, points to the highly relative and unstable boundary between “modernist” and “postmodern” neo-noirs. Furthermore, Naremore (1998) points out that “even when parody ridicules a style, it feeds on [and shows affection for] what it imitates” (p. 200); in addition, parodies of the noir genre, and even noir films verging on self-parody, existed even during the age of the classical noir (p. 201). Naremore directly challenges Jameson’s pessimism about neo-noir pastiches, claiming that “Nostalgia may be pervasive in the new film noir, but it is also a theme in the ‘original’ [classical] pictures—which…usually involve the sort of protagonist who ‘retreats into the past’” (p. 211). He insists that we should not flatly dismiss all neo-noirs, as Jameson does, but instead judge each neo-noir film on an individual basis, deciding whether or not nostalgia and “retro noir” styles are being used to invoke a “conservative, ahistorical regression” (p. 211).

6.

Singapore Sling takes the common feminist/psychoanalytic reading of film noir and raises it up from the subtext, explicitly placing it on full display. Gledhill (2000) explains how films noirs involve a male protagonist investigating “an event that either happened or is about to come to completion” (p. 76), with the femme fatale often serving as a key to the mystery, conflating investigation of a crime with investigation of “female sexuality and male desire within patterns of submission and dominance” (p. 77). Laura is a prime example of this narrative trait, given that the apparent murder victim and the femme fatale are one and the same, tied together in a sort of fatalistic web of death, allowing McPherson to effectively “fall in love with a corpse,” as Lydecker remarks at one point. The woman in question is “seen from several [male] viewpoints,” leaving several men struggling for control over Laura’s image (exemplified by her portrait), particularly through the processes of memory visualized as flashbacks (p. 80).

In Singapore Sling, there are two femmes fatales: Mother and Daughter. The titular detective investigates the disappearance of Laura—who, as we learn from the start, was murdered three years ago by the two women. There was once a Father as well, but he has also been gone for several years now (and was away hunting when Laura’s murder took place), and it remains unclear what happened to him. The Daughter tells us that some day he will return to commit horrible deeds—though this turns out to be a sort of symbolic foreshadowing. Her desire for her Father is a sort of Electra complex, given that he incestuously took her virginity in the attic—and that location is where she tells us, in no desexualized terms, of his future return, alternately discussing her desired freedom to smoke cigarettes (an activity forbidden by her Mother) and commenting about her Father pissing. Now that the Father is gone, it is Mother and Daughter’s task to kill and bury their servants. The women have effectively taken over the Father’s role (including his patriarchal power to kill)—especially the Mother, who still retains a degree of control over her Daughter. Just as the femme fatale in films noirs is typically portrayed as a phallic figure (not only by challenging male authority and asserting her independence, but also in her slinky, fetishized attire like stiletto heels and nylon stockings), the Mother literally possesses a sort of disembodied phallus (all the more threatening due to its disembodiment from the male seat of power) in an early sex-play scene in which she forces her Daughter to perform fellatio on a strap-on dildo before fucking her with it.

Manipulated by the femmes fatales, the character of Singapore Sling emerges as a sort of condensation of the three males from Laura. Like McPherson, he investigates the apparent murder of Laura, with whom he is in love. Like Shelby, he was willing to pin a different woman’s death on anyone to prevent Laura from being implicated in the crime (which led to Singapore Sling’s firing as a detective three years earlier). And like Lydecker, he becomes willing to kill “Laura” (whom he has mistaken the Daughter for) when he realizes that she will not end up with him. After slowly regaining the ability to move around the villa and use language again, Singapore Sling finally kills the Mother (with the help of the Daughter, who had earlier explained that she and her Father would have killed the Mother long ago). He also steals the Father’s “big knife” from the attic and, with this recovered phallus strapped on like the dildo wielded earlier by the Mother, he fucks the Daughter to death with it. This destructive and misogynistic punishment of the femmes fatales as the disempowered male protagonist recovers his phallic sexual authority at film’s end could, in a sense, not be more loyal to the narrative traditions laid down by classical films noirs, essentially differentiated from such earlier films only in the degree to which the psychoanalytic subtext is made so graphically literal.

7.

Krutnik (1991) and others have described noir narratives as masochistic, involving a male protagonist whose sense of identity is directly tied to his threatened sense of sexual authority. His struggles to solve the mystery at hand are reflected by his inability to control the femme fatale, whose “dangerous” independence and phallic power often translate into sadism and cruelty. The predominant use of flashbacks and subjective voice-over narration is often pleasurably misleading for viewers (masochistically shattering our hypotheses about the plot) because the detective may be mistaken in his assumptions about the case. The highly restricted narration of films noirs carefully controls the amount of information that the viewer receives, keeping the mystery intact until the end—and even when the mystery is finally solved, there is regularly some doubt about how this solution was achieved. Chance events tend to break the case open more commonly than the protagonist’s own investigatory strategies, weakening the film’s sense of closure by calling into question the conventional causality of classical Hollywood narration. As Gledhill (2000) says, “the plots of noir thrillers are frequently impossible to fit together even when the criminal secret is discovered, partly through the interruptions to plot linearity and the breaks and frequent gaps in plot produced by the sometimes multiple use of flashback” (p.77). Although time and again he wallows masochistically in some past guilt or pain, the protagonist also acts out in sadistic ways (e.g., the voyeurism implicit in his investigation of the woman), as if to reaffirm his threatened sense of power and dispel feelings of vulnerability. Narrative closure typically involves the protagonist sadistically punishing the femme fatale and reasserting his sexual dominance, if not also his investigatory competence.

Following from the conventions of the genre, sadism and masochism play a decisive role in Singapore Sling as well. The cinematography and mise-en-scène are blatantly fetishized—and here it must be emphasized that fetishism is psychoanalytically linked to masochism by investing desire in a surrogate object instead of the preferred (absent) object of one’s desire—turning the villa into a sort of masochistic heterocosm in which nightmarish fantasies are given full reign. Various fetishes fill the screen at every given moment, from the bondage attire worn by the main characters, to the villa’s decadent interiors, to the lush interplay of light and shadow (which treats the noir’s visual style as a sort of fetishized lost object in itself). Sex play and perversely reenacted fantasies motivate much of the film’s action, with various filmic scenes resembling BDSM “scenes.” Mother and Daughter are both archly sadistic femmes fatales, intent on torturing Singapore Sling until he explains why he is looking for the murdered Laura. But this sadism is not only reserved for the detective: within an earlier sex-play scene (“the game of the young secretary”), in which the Daughter plays as Laura, the Mother first demands that all female servants must be virgins and “good girls,” then proceeds to rape “Laura” in a sort of corruption of innocence worthy of the Marquis de Sade’s best efforts. They starve Singapore Sling while making him watch as they gorge themselves with bare hands until they vomit, and later reward his confession by forcing him to eat until he vomits likewise. They tease him sexually and force themselves upon his unconscious or incapacitated body. In one particularly shocking scene (pun intended), the Daughter applies electroshock paddles to a metal halo screwed into Singapore Sling’s skull while the Mother rides his convulsing body before pissing in his face as she reaches orgasm.

8.

Introducing himself in subjective voice-over narration, Singapore Sling fits the immediately recognizable generic role of the detective protagonist, and we are thrust into his head via that inner monologue. Undoubtedly our identification with such a flawed, delirious, and disempowered “hero” is masochistic if we identify with his cruel mistreatment, unstable identity, and failed attempts at either finding Laura or saving himself. (Unlike most classical films noirs, we have far more knowledge than the detective does throughout Singapore Sling, such as the fact that he has mistaken the Daughter for Laura.)

If the character of Singapore Sling represents the sort of investigative narrative logic associated with the traditional noir, the Mother and Daughter serve to undercut that logic. Singapore Sling’s voice comes almost entirely in the form of a subjective voice-over and then only intermittently, in the beginning, middle, and end of the film. He can still think (though his ideas are scattered and mistaken), but cannot physically talk. In contrast, the Mother and Daughter speak directly to the camera, breaking the fourth wall as they address us as viewers. Their voices motivate the film’s flashbacks and other narrative jumps, not Singapore Sling’s—making them speaking subjects as well as sexual objects. They are even given more screen time than the detective himself, encouraging us to also identify with them. Indeed, more of the film is devoted to their investigation of Singapore Sling’s motives than to the detective’s own active inquiries into the disappearance of Laura, such as when they go through his notebook and ask of him the same questions that he has written down about Laura (all of which directly reference the plot of Preminger’s Laura).

Gledhill (2000) posits that “the plot of the typical film noir is…a struggle between different voices for control over the telling of the story” (p. 79). The use of flashbacks can create a distance between the subjective voice-over and the actual events portrayed, “leaving room for the audience to experience at least an ambiguous response to the female image and what is said about her. […] Thus the woman’s discourse may realize itself in a heroine’s resistance to the male control of her story, in the course of the film’s narration” (p. 79). I am certainly not trying to claim Singapore Sling as a feminist-oriented film in any substantial way (especially given the film’s ending and its sexual objectification of the women), but the film’s displacement of identification and agency from the detective onto the femmes fatales represents a compelling spin on the genre—especially given its relation to Laura, a film described by James Naremore (1998) as “an unusually feminist narrative for its day” (p. 222), featuring a titular femme fatale who is not only strong-willed and independent, but who asserts her ability to follow her desire and is not destroyed for it (even if she may end up somewhat domesticated, as the “good-bad girl” often is).

In Singapore Sling, the character who arguably emerges as the central figure of our identification is the Daughter. She is a sort of good-bad girl (albeit veering more often toward the bad), positioned as the Mother’s ally, but also somewhat sympathetic to Singapore Sling’s travails, maintaining an air of innocence even in the midst of her violent acts. She is both giver and receiver of pain—a sadomasochistic figure at the heart of the film—taking pleasure in torturing the detective but also chaffing against the cruel sexual whims of her Mother. As spectators, we are encouraged to respond in kind: sharing in her sadistic pleasures through the film’s frequent recourse to grotesque black comedy, while still hoping that her freedom from the Mother will end not only her part in the crimes, but also our viewing of such offenses. Like the good-bad girl Laura in Preminger’s film, the Daughter slowly becomes closer to the detective (eventually enlisting his help in killing her Mother) and her true motives become increasingly ambiguous. She assumes the Laura persona to the extent that she becomes wrapped up in her own deceptions—but unlike Preminger’s Laura, the Daughter is finally destroyed to atone for her litany of cruel transgressions.

9.

Singapore Sling ’s narrative follows a roughly circular course, not unlike many films noirs. However, much of the film’s action takes place through a series of flashbacks and sexual fantasies involving sadomasochistic role-playing. This sense of play permeates the film, setting the detective’s inner monologue apart from the more self-conscious narration delivered directly to the camera by Mother and Daughter. Past and present blur together constantly, for the women’s sex play often stands in for flashbacks, reenacting the past in (ostensibly) the present. Subjective processes of memory and fantasy mesh with differing temporal planes to produce disorienting effects.

For example, the Daughter, seated in front of the fireplace with dirt on her face, explains at the beginning of the film (speaking in past tense) that she and her Mother had murdered Laura three years earlier—but then she notes: “Mother and I often play the game of the young secretary, which always begins with Laura setting foot in our house for the very first time.” As she introduces this sexual scenario, the film cuts to her entering the house, now playing the part of Laura. “I make my entrance dressed as a young secretary and holding a small suitcase,” her narration continues (now in voice-over) as the scenario begins playing itself out onscreen. Here she narrates the scene in the present tense, but we are left unsure of when this fantasy is taking place—presumably in the recent past—especially because they apparently “often” play this game.

As the game continues and the Mother begins forcibly fucking the Daughter-as-Laura, the film suddenly cuts to a shot of the Daughter peacefully drinking tea at the kitchen table, but the sound of her sexual moans bridges over into this new shot. The Daughter looks up, as if reacting to the sound, and a reverse shot reveals Mother and Daughter stumbling into the kitchen, struggling with one another as the Mother produces a knife. Again the film cuts back to the Daughter smiling and watching as the Mother stabs Daughter-as-Laura, spilling her entrails into the sink. This is followed by several shots of Mother and Daughter (now dressed differently) removing the guts from an off-screen body (that of the real Laura). This initially perplexing series of shots jumps from a flashback of Mother and Daughter’s sexual role-playing into an actual flashback of the murder that the sex play is reenacting, the transition visually marked by the graphic disembowelment as Mother stabs the real Laura (whose face we never see). The unmarked jump from the Daughter’s flashback in front of the fire to her flashback in the kitchen is what makes the scene especially confusing at first glance, especially as she thereafter resumes her fireside narration, leaving the shots of her at the kitchen table temporally unexplained.

The Daughter proceeds to repeat a similar pattern, explaining how it was her Father’s role to kill the servants in the past. Then she sets up another flashback—“I remember the day that Father took my virginity”—before we cut a sequence of her being fucked by her Father (wrapped up like a mummy) in the attic. Here she has transitioned again to an apparent flashback, but now the memory is not only shown to us, but explained from within the memory itself. Gasping with pleasure, she continues her narration directly into the camera as the sex scene unfolds, observing that “I was very young then…only eleven years old.” She thus narrates the flashback not only from an “outside” position in the present (her language moving from past tense to present tense as she sets it up), but also from within the temporal space of the flashback (now speaking in past tense about events apparently occurring right before our eyes), even narrating her Father’s dialogue for him. However, the fact that these events occurred many years earlier (when she was eleven years old) but are effectively reenacted at the Daughter’s present age, suggests that a supposed flashback has again jumped instead into a memory of sexual role-playing. The fact that the Father is dressed as a mummy could punningly allude to another instance of the Mother (whom the Daughter often refers to as “Mommy”) taking up her phallic role as not only a killer but a fucker. (In yet another twist, it may more closely resemble Singapore Sling under the bandages, which would make this scene a flash-forward to his more active role in the sex games later in the film, such as during a threesome in which we see several quick shots of this same scene of the Daughter and “Father.” The possibility of a false Mummy/Mommy also invites questions about whether Mother and Daughter are actually related, due to their apparent closeness in age.)

10.

Singapore Sling??’s interwoven flashbacks and sexual scenarios highlight the way that flashbacks and self-conscious (often misleading) narration are already a familiar generic aspect of films noirs, using desire (often focused around the femme fatale) to motivate their highly subjective narratives. ??Laura, for example, begins not with McPherson’s hardboiled voice-over framing the film as a flashback, as we might expect. It instead opens with Lydecker’s voice-over as he describes the weather on the weekend that Laura “died,” claiming that he was the only one who really knew her. This is, of course, misleading because later we learn that (unbeknownst to Lydecker) Laura is actually alive and has very different motives than Lydecker believes. “Another of those detectives came to see me,” he says as McPherson is introduced to us, speaking in past tense as he seemingly engages his memory. The film thus initially appears to be narrated by Lydecker as a flashback. However, the remainder of the film is clearly not Lydecker’s story, for his narration does not continue during the film (apart from one possible flashback with a flashback, in which he describes to McPherson how he met Laura) and because many events are shown which are not focalized through him, and of which he could have no knowledge. Furthermore, Lydecker is eventually killed in the film’s final moments, requiring the film’s opening narration to have effectively been coming from beyond the grave—something that the film never fully explains. This strange confluence of past and present in the same moment is not altogether unlike the bizarre effects produced by the narrated flashbacks/fantasies of Mother and Daughter in Singapore Sling.

“I have a premonition that something bad is going to happen to us,” the Daughter tells us early in the film, just before Singapore Sling appears on their doorstep. Her premonitions, which will turn out to be true, are observed in present tense, but she immediately begins narrating present actions in past tense: “We planned on having a quiet evening when, all of a sudden, we were startled by a sharp ring at the door.” The doorbell rings at that moment, and she continues—‘“Who could it be at this time of night?’ Mother asked me”—just before her Mother repeats the same sentence. This anticipation of dialogue seemingly validates the Daughter’s premonitions and collapses together past, present, and future into the same temporal space. The Mother also has premonitions of her own—a seeming obsession with (fish?) scales—which she relates to drops of semen left around the house. After finding scales scattered here and there, she is later netted like a fish and stabbed to death with a trident-like pitchfork while sitting in the bathtub.

11.

As in the classical film noir, ontological identity in Singapore Sling becomes tied to sexual identity. The mystery of the femme fatale is traditionally the key to solving the male detective’s dilemma, and his threatened sense of control over the world is linked to his sexual control over her. Utterly disempowered by the two women, he continues to follow his desire for the mysterious Laura, that search existing as an external signifier of identity as he becomes forced to rely upon the sadomasochistic sex play of Mother and Daughter. His already fragile identity is emphasized by the fact that we never really know his real name, for the two women dub him “Singapore Sling” after they find a recipe for the drink of the same name in the detective’s wallet when they search him for clues about his motives. As if devoid of a personal identity, the alcoholic detective becomes named after a favorite drink—“a cocktail they used to drink in the old days,” as the Daughter says (though we later learn that two glasses of Singapore Slings were found at the scene of Laura’s murder, as if fated to be so by the film’s internal logic).

Mistaking the Daughter for Laura upon his capture (for she wears Laura’s earrings), Singapore Sling becomes convinced that he must save her from the Mother. As an unwilling participant in their tortures, his sense of identity is potentially all the more at risk—hence the film’s dreamlike, almost nightmarish tone. After he is subjected to electroshock torture, his mind seems all the more shattered, his desire and identity increasingly externalized onto thoughts of Laura, and he decides for certain that he has finally found her. Of course, the Daughter plays into his misapprehension as she attempts to coax information out of him, calling herself Laura and saying that she loves him, while making up reasons for her apparently mistaken death (taken directly from Preminger’s Laura).

However, this is not to say that the various fantasies and sexual role-playing engaged in by Mother and Daughter have left their own identities unaffected. Though the Daughter’s primary intention is to get information out of Singapore Sling by playing the role of Laura, she also resents her Mother and wishes her dead. There is then a certain extent to which she actually does wish to escape with the detective as Laura, and she gradually pits him against her Mother. We eventually see slippages develop between her own identity and the role she is playing. Even when alone with her Mother, she keeps up the act; for example, she wants to escape in Singapore Sling’s car against her Mother’s wishes and must explain to her Mother that she wishes to go tell her friends that she is still alive (just as Laura wished to do after discovering herself supposedly “murdered” in Laura). In this scene it becomes difficult to see where the Daughter’s masquerade ends and her true intentions begin.

Likewise, this scene is immediately followed by the Mother grabbing Daughter-as-Laura to interrogate her in front of Singapore Sling (using much of the same dialogue from an interrogation scene between McPherson and Laura near the end of Preminger’s film). “Did my daughter pass by, or maybe Laura?” the Mother asks the detective, not knowing who he will identify the woman as, but also as if somewhat unsure herself. When the Mother begins mentioning to her Daughter that they had killed Laura together, the Daughter becomes upset. Not only does this good-bad girl wish to preserve the illusion within earshot of Singapore Sling in order to wring information from him, but she also seemingly has a larger stake in playing Laura. As she moves toward eventually killing her Mother with the detective’s help, making Laura part of her sense of self becomes a greater priority, effecting a sort of splitting of her identity. For example, at other times she seems convinced that the mythical woman is still alive, concernedly asking herself and her Mother what will happen to Laura.

Throughout the film, the two women (but especially the Daughter) seem to slip in and out of character, as if becoming lost in the hermetic world of role-playing and sadomasochistic violence that permeates the villa. Their narration sometimes spins off into descriptions of other time periods and events, as if following the processes of dreamwork. Periodically wracked by spasms (of desire?) and stuttering, their deliberately heightened acting style calls attention to the performativity of their identities. Just as the film’s frequent depiction of sex play illustrates the nature of identity as performance, its use of film noir tropes is itself a sort of performance. However, is the noir narrative merely a backdrop for the sex play, or is sex play the backdrop for the noir narrative? Can these two compositional elements be separated, or are they inextricably tied together?

12.

Questions of identity are further explored in the film’s depiction of language. Of course, Lacan and others have argued that identity is constituted through language—and in this sense, the film’s dueling narrational voices fracture our spectatorial sense of identificatory coherence. Shifting identities on the diegetic level are directly related to our relative difficulty in consolidating a stable sense of ego identity as spectators, due to the film’s fragmented narrative and our forced identification with mentally unstable characters. Emphasizing this point is the fact that several languages are spoken in the film—Singapore Sling speaks only Greek, the Daughter speaks only English, and the Mother speaks both French and English (often speaking first in French before repeating herself in English).

Amplifying the conventions of film noir, the full shape of the narrative comes together only gradually over the course of the whole film; indeed, it is not until late in the film that Singapore Sling’s back-story is adequately (though never fully) explained, and only then when told to us by the Mother and Daughter. Furthermore, he is only being kept alive until he explains what he and anyone else know about Laura’s murder. The struggle over language thus determines his entire existence, and his name “Singapore Sling” even derives from the tremendous power that Mother and Daughter hold in being able to name him. He is unable to audibly speak when he enters the villa for the first time, his voice only coming to us as an inner monologue. This inability to verbally communicate becomes especially marked after his electroshock torture—the same point at which his sense of identity and knowledge is drastically damaged. The Mother later threatens to torture and kill “Laura” if he will not talk, so she begins trying to coax him back into acquiring language, treating him like a young child as she makes a game out of speech (teaching him the vowels). Only by telling her what she wants to know about Laura will she allow him to have some water. With the help of the Daughter playing Laura, the Mother finally threatens the detective into talking (though we do not see that confession), but he never actually speaks onscreen (outside of his voice-over) during the entire film.

Unlike Lacan’s assertion that the Father symbolically introduces the child to language, Singapore Sling is reintroduced to language by the Mother—and this produces additional difficulties in developing a stable identity. While, according to Lacan, the ego is always divided and self-knowledge of one’s drives is sacrificed upon the acquisition of language, here we see an “improper” (re)initiation into subjectivity, effecting more blatant disjunctions between knowledge and identity. For example, late in the film, Singapore Sling has gained some measure of trust from Mother and Daughter, being allowed to participate in threesomes with the two women, and even wielding a pistol passed between the three intertwined participants. Increasingly inhabiting the phallic role of the absent Father in this scenario (as his sadistic treatment of the two women indicates), even as he takes orders from the Mother, he still believes that the Daughter is Laura, but his voice-over explains that he is willing to “play the fool” and torture her in order to trick the Mother into passivity (eventually killing her with the Daughter’s help). This segment of voice-over narration indicates just how much of a disjunction exists between the detective’s externalized sense of identity and his self-knowledge. As he steps into the Father role, he mistakenly believes himself to be in a position of greater power by apparently deceiving the Mother, not knowing that he is still being deceived by the Daughter and her matricidal plot. Since subjectivity in films noirs rests upon the externalization of the male protagonist’s dilemma onto the mystery of the femme fatale, Singapore Sling’s assumed position of power and knowledge are thwarted by the Daughter’s deception—and consequently, the detective’s own mistaken sense of self-identity.

13.

Near the end of the film, the Daughter sits before the fireplace with dirt on her face, explaining directly to us that she and Singapore Sling have just killed and buried her Mother. She notes that she can now smoke and has not found her Father’s knife. However, most of her dialogue uncannily repeats her segments of fireside narration from the film’s beginning (e.g., references to the murdered chauffeur now replaced by talk of her murdered Mother), and the scene is filmed in identical fashion. As before, her monologue turns to Laura and she repeats her observation that “Mommy and I often play the game of the young secretary…which always begins with Laura setting foot in our house for the very first time.”

Circularly mirroring the Mother/Daughter sexual scenario portrayed earlier in the film, we cut to the Daughter entering the villa with a small suitcase. After introducing herself under her assumed role as Laura, she kneels before the Mother’s chair; in her voice-over narration (continuing from the previous fireside scene), she begins to speak in present tense: “Now comes the moment to lift her skirt.” However, we suddenly see that something is very different about the scene: Singapore Sling is now seated in the deceased Mother’s chair, dressed in the Mother’s clothing and makeup (appearing almost like a vampire), playing her role as a sort of androgynous figure. Under his skirts, in place of the Mother’s dildo, is the Father’s knife. “This isn’t how we play the game with Mommy!” the Daughter exclaims as Singapore Sling begins forcing her down toward the implement. The detective has shattered the Daughter’s fantasy, but his own vision of the scenario apparently continues as he pursues her, finally exchanging mortal wounds as he penetrates her from behind with the knife-as-phallus before she shoots him with his pistol.

Each person has simultaneously occupied multiple positionalities within a scenario allowing the free play of different confused motivations, destabilizing all stable identities and allowing different circuits of desire to flow through each person, freed from the constraints of conscious intention or concrete subjectivity. The Daughter has occupied both her own role and that of Laura at the same time, as she always had in the “game of the young secretary,” though the division between the two identities is greatly compromised by this late point in the film. Singapore Sling is occupying three positions at once: not only the role of the Mother (filling her vacancy in the “young secretary” scenario) and Father (stepping into his role as phallic destroyer), but also of course his own role as searcher for Laura.

The film ends with the Daughter dying after taking off Laura’s earrings and remarking to Singapore Sling that she was right about him having fallen in love with a corpse. The detective exits the villa, removing some of the Mother’s clothing as he puts his trenchcoat back on. He has finally realized that the Daughter was not Laura after all, but he admits that it doesn’t matter now. Having “chase[d] after a dream with a female name,” he is content to fling himself into an open grave in the garden and pull the loose earth down upon himself (in a shot mirroring the dying chauffeur’s attempts to reach out of the grave at the film’s start), feeling that he will be in good company tonight. As if fulfilling the noir genre’s conventions, he has finally sexually conquered femme fatale “Laura” and solved her mystery at the same time, destroying woman and illusion together, allowing an apparent (if questionable) restoration of his sexual/subjective identity.

14.

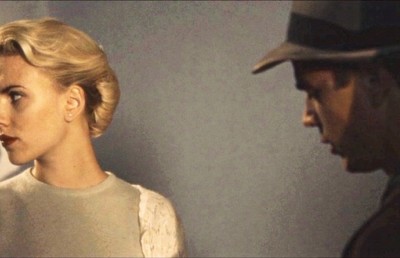

The various circuits of desire at work in Singapore Sling are ultimately destructive, but death never seems to be the absolute end of desire. Identities of the deceased (e.g., Laura, Mother, Father) are resurrected by these flows of desire, temporarily inhabiting the bodies of the film’s surviving players. In this way, the sadomasochism inherent in film noir intersects with the sadomasochistic influence of Gothic horror. Of course, many film noirs share a similar affinity with Gothic horror, dealing with themes of mirroring, the uncanny, tragic love, despair, and psychological terror. Even the visual style of film noir meets Gothic horror halfway in the influence of German Expressionism. Preminger’s Laura is an exemplary film in this regard, foregrounding mirroring, mistaken identities, and the detective’s love for a supposedly dead woman who suddenly reappears mid-film like a ghost. This moment of uncanny reappearance is even initially figured as a sort of nightmare, for the camera tracks in to a medium close-up as McPherson falls asleep in front of the portrait of Laura, pauses for a moment, and then pulls back again to show the portrait as the living Laura makes her entrance. This tracking movement denotes a temporal ellipsis without using a cut, dissolve, or other transition—but it could also be read, at least at first, as a sign that McPherson has entered a dream state in which Laura reappears before him. This is not the case, as the film shortly makes clear, but for several minutes we are left questioning Laura’s presence as the product of McPherson’s subconscious.

The intertextual references to Laura infuse Singapore Sling with a similar sense of the Gothic, though the latter film does other things to associate itself as such—for example, the Father’s appearance as a mummy recalls the Gothic edge of classic 1930s Universal horror movies. Here the “old dark house” setting of Gothic horror replaces the urban jungle typically associated with the noir genre. Destructive desires allow the narrative to move according to an almost nightmarish logic, and the exploitative elements of the plot have even led many reviewers to classify the film within the horror genre, despite its obvious noir pedigree. Premature burials (such as that of the chauffeur) and love for the “living dead” are present throughout the film (e.g., its tagline is “the man who loved a corpse,” recalling Lydecker’s dialogue from Laura), evoking various examples of Gothic horror, including perhaps Roger Corman’s Poe adaptations (indirectly, by way of Vincent Price’s earlier role in Laura). Just as Lydecker narrates the introduction of Laura as if from beyond the grave, Singapore Sling is already dead, in a sense, even before he enters the villa, so his voice-over is also virtually a posthumous one.

“Love is stronger than life. It reaches beyond the dark shadow of death,” says Lydecker’s pre-recorded voice upon the radio, providing a sort of voice-over commentary as he prepares to kill his beloved at the end of Laura. He continues with a few famous lines from Ernest Dowson’s poem “Vitae Summa Brevis”: “Out of a misty dream / Our path emerges for a while, then closes / Within a dream.” As if within a nightmare, destructive desire has led us to this point, but it also extends beyond the grave.

Laura and Singapore Sling use this Gothic trope of “love beyond the grave” as a sort of ode to necrophilia. Both films use flashbacks and fantasy to bring “Laura” back to life before our eyes, allowing us to likewise invest our desire in this ostensibly dead woman. Necrophilia lingers at the edges of each narrative, but of course more explicitly in Singapore Sling , whether with the Father fucking the Daughter dressed as an undead mummy, the detective fucking the Daughter-as-Laura to death with the Father’s knife, or the recurrent references to corpse-love. This perverse desire is reflected by the very form and look of this neo-noir film itself, with its obvious fetish for a genre that some have argued has been dead since the mid-1950s. The noir is temporarily reinvested with life by Nikolaidis, but the intertextual references to Laura ensure that the film never fully disavows the death of classical noir, nor poses as an independent reinvention of the genre. Film noir is treated as something already lost and decayed, primed for campy revivalism or the fleeting moments of resurrection that this film’s extreme fetishization affords.

15.

Besides the film’s visual aesthetic and disorienting narrative effects, the overall narrative can be seen as more postmodern than modernist, given that it is predominantly motivated by desire itself, instead of the male protagonist’s desire (for the femme fatale) secondarily invested into the investigative logic that motivates most classical film noirs. It is a narrative organized less around cohesive characters, identities, voices, and motives than various circuits of desire that flow in multiple directions across time, interconnecting the three characters at strange (dis)junctions. Enveloped within the film itself as a sort of grand sadomasochistic scenario, the players’ seemingly apparent motivations are continually undercut by slippages—whether in time, identity, or narration. These circuits of desire evade even the characters’ self-conscious attempts to verbally contain or control them (via the conflicting narrational voices), propelling the narrative’s ostensibly illogical temporal jumps and constant sense of play—but also evoking masochism’s distinct aesthetic of repetition and fantasy. The film’s array of extreme fetishization and disorienting effects (and affects) overload the traditional Lacanian psychoanalytic reading of film noir, hyperbolizing that interpretation to the point of self-destruction. It lays bare the genre’s underlying current of misogyny, sadomasochism, and perversion in a way heretofore unacknowledged by the film’s critics or scholars. As viewers, we are set masochistically adrift within the intersecting flows of impulses and images—thrust into a strange world in which aberrant acts (incest, torture, murder), perverse paraphilias, and even the mise-en-scene itself are presented as so many libidinally charged intensities. The film challenges our senses and sympathies, provoking a strange mix of sensations as we enter into its cruel world.

However, if read differently, the film’s parodic, modernist potential is deflated by a postmodern use of pastiche that exhibits a hybridized mixing of film noir with horror and (s)exploitation films. The film’s blatant sadomasochistic and psychoanalytic overtones are treated as belonging more to the realm of horror and exploitation than film noir (as evidenced by the fact that many critics classified it as a horror film)—hence the difficulty in reading the film as a modernist critique of the noir genre. This is largely due to the film’s nightmarish tone and sadomasochistic content, with its intentionally shocking emphasis upon “perverse” or non-normative sexuality (e.g., bondage, incest, lesbianism, group sex, etc.), and the titular detective’s subjection to repeated bodily torture and various abject fluids (e.g., vomit, urine, etc.). Following Creed (1996), it could easily be said that this emphasis on sexual violence and abjection committed by two sadistic women reflects conservative male fears of the “monstrous-feminine” as a threat to male authority underlying many horror films. Their ultimate destruction betrays a certain reactionary thrust that challenges any purely affirmative readings of non-normative desire’s role in motivating the fragmented narrative. Modernism and postmodernism are thus forced into a dialogue in any reading of Singapore Sling, in danger of canceling out each other’s more politically viable aspects. On the one hand, the modernist potential of the film’s parodic foregrounding of sadomasochistic and psychoanalytic excess is defused by its postmodern hybridization with horror and exploitation films. On the other hand, the potentially affirmative qualities of a postmodern narrative motivated by shifting circuits of desire (instead of rational logic and stable identities) are ultimately undermined by the film’s adherence to a modernist-inflected noir ending (resolving problems with memory, identity, sexual authority). Modernism becomes merely another style co-opted into pastiche by the postmodern film, lingering as traces within the text, but finally subject to an evacuation of meaning. Nevertheless, Singapore Sling deserves inclusion within the (neo-)noir canon as a fascinatingly idiosyncratic re-reading of the genre and yet another example of a critically neglected cult film with much to offer the well-worn environs of the academy.

Frame grabs of the film were taken from the 2006 Synapse Films DVD release.

Bibliography

Creed, B. (1996). Horror and the monstrous-feminine: An imaginary abjection. In B.K. Grant (Ed.), The dread of difference: Gender and the horror film (pp. 35-65). Austin: University of Texas Press.

Eco, U. (1985). “Casablanca: Cult movies and intertextual collage.” SubStance, 14(2), 3-12.

Gledhill, C. (2000). “Klute 1: A contemporary film noir and feminist criticism.” In E.A. Kaplan (Ed.), Feminism and film (pp. 66-85). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Jameson, F. (1983). Postmodernism and consumer society. In H. Foster (Ed.), The anti-aesthetic: Essays on postmodern culture (pp. 111-125). Seattle: Bay Press.

Krutnik, F. (1991). In a lonely street: Film noir, genre, masculinity. London: Routledge.

Naremore, J. (1998). More than night: Film noir in its contexts. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Schwartz, R. (2005). Neo-noir: The new film noir style from Psycho to Collateral. Lanham, MD, Toronto, and Oxford: Scarecrow Press.

Spicer, A. (2002). Film noir. Harlow, UK: Longman.