Lust, Love, and the Question of Transgression in Patrice Chéreau’s Gabrielle

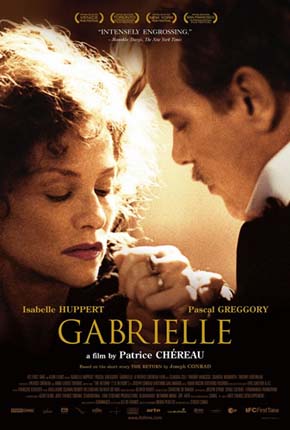

In light of the most recent work of Taiwanese-born American filmmaker Ang Lee’s Lust and Caution (2007), I propose a reading of the notions of lust and love towards an analysis of the definition of transgression and love in the French filmmaker Patrice Chéreau’s latest film, Gabrielle (2006). Gabrielle, a film based on Joseph Conrad’s novella The Return (Tales of Unrest, 1898), introduces a married couple whose fate is traced from the very beginning of the narrative. Patrice Chéreau displays the concept of “returning” as a form of aporia of marriage and its vicissitudes regarding love and desire. From the onset of the film, it seems that the couple is bound to separate. There is no love in their relationship. However, their choice is to remain tied to each other due to the numerous social conventions of which they partake, and which they, to a certain extent, enjoy.

My primary goal is to investigate the question of lust commonly perceived as a taboo, a transgression, a concept situated beyond desire. Lust falls apart in face of the recurrent cynicism and hypocrisy, an idea that deserves a more critical explanation. Desire, or the acting out of lust, is linked to the unknown, the unconscious, and the emotional self that does not need to face the Other. Nevertheless, lust propagates the search for the unknown in a final way: an ultimate encounter after a long search. There are no significant open doors when lust comes into place. In its most traditional conception, desire fades away from the relationship with the Other, leading to the fact that the acting out of lust dissolves desire. Still, I must point to the perspective that what the spectators notice on the screen relates to the traditional idea that renders love as the real taboo in Gabrielle, resounding into one’s primary lack, rather than lust, as typically implied when it comes to a clear-cut definition of desire in love. In fact, one realizes that the latter proves to be more accommodating within the individualistic and selfishly opinionated status quo of the fin-de-siècle French society. Despite the fact that the film takes place at the turn of the century, it creates an atmosphere that makes the film amenable to a post-twentieth century—and contemporary— psychoanalytical study. Therefore, in order to promote an analysis of what has become the major transgressor in the current social framework, and inspired by the aesthetic and ethics of the latest Chéreau’s réussite 1 , one must propose a new comprehension of the meaning of love.

By considering love as the real impossibility, as the actual transgression that may happen, I will draw from Slavoj Zizek’s considerations of Lacan’s works. Slavoj Zizek’s analysis of Hollywood films helps to demonstrate that lust has not lost its appeal in the midst of the current hectic Western life style. Love has slowly faded away from the screen and life, although it fits well into the Lacanian concept of the imaginary/symbolic/real triad 2 . The first concept mentioned, i.e., the imaginary, refers to the realm of the Lacanian hic et nunc (from the Latin here and now, meaning the idea of present and its certain existence and disappearance). Lacan’s conceptualization of language as a means to convey the unconscious leads to a gray area that underlines the profound solitude which human beings “impose upon themselves” or “choose” as their temporal-spatial setting for life. Again, as a theoretical background, Zizek’s Cultural Studies observations echo Lacan’s notions of the triad of the real, the symbolic, and the imaginary, a triad called into question in the very definition of the psychoanalytical Other, as explained by Zizek: “the big Other is fragile, unsubstantial, properly virtual, in the sense that its status is that of a subjective presupposition” (Zizek, How to Read Lacan, 10). In addition, one needs to claim that without the challenge of the fragile Other, there would be no possible interpersonal exchanges to simply clarify its importance, although the question of ‘existing exchanges’ remains to be deciphered. I follow thus Lacan’s idea of desire which is reinvented by the exterior existing gaze and by the affirmation that the current taboo subject in Gabrielle is love, a notion that requires the presence of the Other, nevertheless not mere love as commonly postulated by society under the normative and safer rules to be adopted as life style –being logically opposed to lust, which is represented as proof of unstable, deceitful, and frivolous desire. The rendition of Patrice Chéreau’s Gabrielle proves that both elements (lust and love) have to be closely re-examined, for there are no truthful responses since the idea of “truth” is discarded as soon as love or desire are mentioned. Love appears as the “I” objectified, the one that promotes its vision through the eyes of the Lacanian Other, to be defined in relation to another one’s desires,’ leaving thus, a trace for the Lacanian axiom, I only desire what the Other sees in my desire or more specifically, “ (…) –man’s desire is the desire of the Other (Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, 38). In effect, I erase myself from the arena of ‘wanting’ as long as I am pleasing my supposed subject of affection, imagining I’m giving him / her the key to my thoughts and to my body. Therefore, I become the object of the Other’s inner existing complexes, including traumas; and, finding myself passive in regard to this stratagem, my desire renders my-self powerless because of the nature of its painful gaze; or as Zizek puts it; “Ce qui est ainsi insupportable dans ma rencontre avec l’object, c’est qu’en lui je me vois sous la forme d’un objet qui souffre; ce qui entraîne ma reduction au statut d’observateur passif et fascine, c’est cette scène où je me vois souffir au dehors” (La subjectivité à venir. Essais Critiques, 43). (What is unbearable in my encounter with the object, is the fact that I see myself as the painful part of a suffering object; which takes me to the status of being the passive and charming observer, it is the scene where I see myself suffer from the outside.) By becoming the object of the Other’s wishes my grounds turn uneven, and my desire transformed into something unknown. An unknown that was known, that I can no longer recognize, an idea keen to Zizek’s when presenting the game between consciousness and unconscious, desire [désir] and knowledge [savoir].

Chéreau’s Gabrielle narrative focuses on the female character’s observations, although the narrative is delivered in first person by the male character, Alvan Hervey, in Conrad’s novella, whose adopted name by Chéreau is Jean. The name Jean conveys the male protagonist’s own simplicity, mainly because there is nothing hidden or complex about him, as opposed to Gabrielle, whose mind hides the unknown desire for the desire of the Lacanian Other.

Gabrielle displays her impassible persona, not demonstrating the desires she carries within, although her character brutally evolves to the point of unveiling her naked face to the man she loves and to the one she does not love, but is married to. Gabrielle’s character develops toward a wish to be with, the Other, a desire to be caught and not liberated by the love of the lover. Gabrielle’s senses dictate that ‘je est un autre’, to quote Rimbaud’s famous line, i.e., Gabrielle displays another skin by letting herself be guided throughout the labyrinth of her unconscious in the act of pursuing love, the ultimate unknown, the one that belongs to the real of the Lacanian real, one never to be uncovered nor attained by the structure of language or consciousness. If one is caught in the net of love, the result should prove a disaster, since love explains nothing, promises nothing, and understands nothing. Love remains at the central stage of frustration, at the core of the real that ignores the space and time we are actually plunged into. The lack that drives human beings results in their perceiving and trying to heal by abusing their desire of love (if love displays the characteristic of tangibility). The essential question that remains, disturbs the epicenter of the whole speculative “elective affinities”; i.e., ‘do I really want this love?’ It suddenly unveils the weight that carries the demand for love, a concept perceived as another form of game within the ideological love framework, as for instance, courtly love designed in twelfth century France; “I want it but I don’t want it, to quote Zizek, “Along with every demand, a question necessarily rises: ‘I demand this, but do I really want it?’ ” (Zizek, Slavoj, Looking Awry, 21). Apparently no, in the case of Gabrielle all certitude of a passionate encounter dissolves into air as the encounter happens, unfolding the myriad of unknown obstacles.

As the film starts, one observes Jean leaving the train in his bourgeois outfit, narrating the peaceful and uneventful life he leads with his wife, and the joy he derives from it. As the opening scene progresses, the spectators learn that today is a special day, because Jean is returning home earlier than expected. He explains his life situation in a black and white cinematography and monotone voice, praising that his is the utmost perfect life, and especially because of his perfect marriage. Since there is no intimacy between the two of them, as he says, his desire has found peace after ten years of marital life. They have common friends who come for dinner and talk on Thursday evenings. Jean and Gabrielle’s flamboyant soirées are expected by each one of the members of their social circle who are eager to perform, drink wine, and talk politics or literature. As Jean finishes his narration at the train station during the opening scene, the film cuts to his wife Gabrielle, played by French actress Isabelle Huppert. With her white blurred appearance, a show of colors determines the tone of the film. While Jean remains in a black and white surrounding, Gabrielle brings color to the screen, in spite of her cold-tempered and absolutely studied behavior. Gabrielle does not make mistakes, the kind of mistakes one qualifies as gaffes. Her life is also perfect, and her maids attend to her as if she were a queen, which, in fact, she reveals to be, in the sense that she does not refrain from her own needs and commands her employees as subalterns with an ear toward her monologue on the love and happiness she had once. That afternoon, Gabrielle arrives some minutes after her husband, in the process missing the opportunity to collect a good-bye letter she had left earlier for Jean. The letter briefly explains that she was leaving her husband for another man, one she loves. Gabrielle’s letter leads to a revelation of the most unexpected marital confrontation. Gabrielle’s return sets the focus of the film plot: despite the love she has for this other man, she confesses to her husband that a life with the man she truly loves would absorb too much of herself, and she could not abide living that way. On the other hand, Jean / Harvey’s reaction to the letter reads as in Conrad’s novella The Return: “Life that to a well-ordered mind should be a matter of congratulation, appeared to him, for a second or so, perfectly intolerable” (The Return, 13). His feelings are narrated in detail as they were written by Conrad and seen on the screen:

It was terrible – not the facts but the words; the words charged with the shadowy might of a meaning that seemed to possess tremendous power to call Fate down upon the earth, like those strange and appalling words that sometimes are heard in sleep. They vibrated round him in a metallic atmosphere, in a space that had the hardness of iron and the resonance of a bell of bronze. (The Return, 12-13)

In reaction to Jean’s malaise, I will add the definition of love as coined by Slavoj Zizek [[fn3. Secondly, love is therefore an inherently historical phenomenon: its concrete configurations are so many (ultimately failed) attempts to gentrify, tame, symbolize, the “unhistorical” traumatic kernel of jouissance that makes the object unbearable. Thirdly, love is never “just love” but always the screen, the field, on which the battles for power and domination are fought. Is voice, as a catalyst of love, not the medium of hypnotic power par excellence, the medium of disarming the other’s protective shield, of gaining direct control over him or her and submitting him or her to our will? Is gaze not the medium to control (in the guise of the inspecting gaze) as well as of the fascination that entices the other into submission (in the guise of the subject’s gaze bewitched by the spectacle of power?) (Zizek, Gaze and Voice as Love Objects, Introduction, 3).

]]. It stands as pertinent to the comprehension of Patrice Chéreau’s introduction of love as a forgotten, unnecessary notion in marriage. Love touches what is unimaginable, i.e., the Lacanian real that proves to present danger to a couple who consider themselves ‘steady,’ in a situation where habit is more important than anything else. A displaced piece can damage the whole puzzle or, even more precisely, destroy the art gallery that Jean hosts in his house, a gallery in which Gabrielle appears as the final art object, the one that should remain intact –thus the lack of sexual / sensual life between the estranged couple. Gabrielle never reveals herself, she merely is. Patrice Chéreau presents the idea of art objects as a sort of metonym to Gabrielle’s being. She is the work of art her husband most cherishes. Gabrielle emulates beauty as if her existence proved to be a sculpture, a painting-like ‘aura’ overlooking her body. As the spectator observes during the final scene, Gabrielle lays in bed half naked wearing a silky burgundy robe covering parts of her marble-like body. Just like a white, cold statue, she offers herself to Jean, who refuses taking her, because he wants love and not the motions of lust quickly produced during a sexual encounter. And Jean says in anger, and as a form of revenge: “Ce que vous me racontez n’a rien à avoir avec l’amour!” (“What you are telling me has nothing to do with love!”) Renata Salecl and Slavoj Žižek elaborate on the notion of love, as demonstrated on screen by Chéreau by saying:

First, love cannot be reduced to a mere illusion or imaginary phenomenon: beyond its fascination with the image of its object, true love aims at the kernel at what Lacan called l’objet petit a. Love – as well as hate – is supported by what remains of the object when it is stripped of all its imaginary and symbolic features. 3 (Zizek and Salecl, Gaze and Voice as Love Objects, 3)

After having read Zizek’s quotation above, and according to the psychoanalytical definition, it is understandable that love belongs to the realm created by Jacques Lacan of the real, a domain that according to Slavoj Zizek represents simultaneously the most intimate and the strangest part of a being (La subjectivité à venir, 9). Love does not belong to either the symbolic or the imaginary domains, the first being submitted to language itself and its multitudes of obstacles in expressing one’s wishes, and the latter representing the domain where one wanders and intends to take love to the ground of one’s dreams and creativity. Love, however, states what one is unable to unveil, to dominate, or to clarify, and yet, as Slavoj Zizek defines the domain of the real in another moment, “Le réel ne se découvre qu’à travers l’inconsistance du fantasme, dans le caractère antinomique du support fantasmatique et de notre expérience de la réalité” (Slavoj Zizek, La subjectivité à venir. Essais Critiques, 17). (“The real is unveiled solely through the inconsistencies of the fantasme, in the antynomical characteristics of the fantasmatic support and through our experience of reality.”)

It is indeed the fact that love is experienced as the real fantasme that produces a myriad of unknown and scary sentiments. For this reason, Jean and Gabrielle realize that what they never quite grasped in their relationship as a couple is precisely the experience of love. Gabrielle says to Jean that by taking a lover whom she actually loved, she had a chance of feeling love at least once in her lifetime. And Jean, at a desperate moment, screams: “Tout quitter? Mais pourquoi? Par amour? Au fond, je ne sais rien de vous.” (“To leave everything behind? But why? Because of love? In the end, I know nothing about you.”) The idea that Gabrielle could have experienced a feeling foreign to Jean devours and renders him unable to cope with her return, as well as with their further conversations regarding the nature of her desire to leave. Gabrielle’s unexpected consequent inability to remain with the man she loved is due to the fact that the act of love and its admittance is the real transgression in this scenario. In order to live with the man she loved, she needs to kill love, to be absorbed by it, and Gabrielle senses she is unable to be part of such a fugitive game. For, in order to fully love, one has to understand its natural drive towards destruction by deciphering the Other’s secrets and habits. Living love with a lover requires a certain strength that Gabrielle does not have; to love meant to her and possibly to her husband and also lover, a fall from the real into the symbolic, the realm where language is bound to fail in the task of giving enough to express one’s passions and frustrations. As Zizek explains it, “La leçon à en tirer est que l’on n’atteint pas le réel en levant le voile du fantasme pour se confronter à la dure réalité” (Zizek, La subjectivité à venir, 17). (“The lesson one derives from this says that one does not achieve the real by lifting the veil of the fantasme to face the hard reality.”)

Gabrielle’s statements and attitude surprise and scare her, as she describes her experience during an intimate conversation with her personal maid: “J’ai été heureuse une fois. Je le sais parce que je l’ai été une deuxième fois. Je n’avais pas compris.” (“I was happy once. I know it because I was happy a second time. I had not comprehended it.”) Having experienced happiness twice in her lifetime transforms the whole idea of intimacy and promotes a new turbulence that comes from the man she fell for, a life which Gabrielle can not share because she can not comprehend it. Love represents the mystery of the unconscious, and as Lacan defines it in his Seminar XX Encore: love is the subject taboo of a marriage or a liaison, and the real is part of this mystery. Lacan states that love procures its focus in the philosophical matter, and that the real is the “mystère du corps parlant, c’est le mystère de l’inconscient” (p. 165). (“It is the mystery of the speaking-body it is the mystery of the unconscious.”) Zizek poses the crucial question that may be observed in this context; “L’amour, ai-je besoin d’accentuer qu’il est au cœur du discours philosophique? (…) l’amour vise l’être qui, un peu plus, allait être, ou l’être qui, d’être justement a fait surprise” (Lacan, Encore, 51-53), Zizek and Salecl, Gaze and Voice as Love Objects, Introduction, 3). (“Love, must I emphasize that it is within the core of the philosophical discours? (…) love observes the being that was going to be a little longer, or the being that precisely is the one who poses surprise.”)

In Patrice Chéreau’s Gabrielle, there is indeed a surprise –one that is curious and unpredictable at all levels– and not only because Chéreau makes sure that Gabrielle’s return does not remain in the realm of the Lacanian lack by not achieving what should be ‘the one love’; but because the director adds to the impossibility of the “real” the probable encounter of facing it. Gabrielle turns her face opposite from her lover, the one who could give an answer to her curious desires of having him, simply because such a concept seemed unbearable to her. To take love as a “pure, unique choice” is to demean its vulnerability and to strength it over one’s life.

In conclusion, the taboo concerning love is the fact that it does not accomplish or explain anything; the ultimate meaning of life does not exist in its presence and context. Chéreau’s film resides in love’s own inconstancy, fluidity, and never-achieving realization, due to the final inability of the couple to share their desire into their mental-bodies. In effect, love promotes one to realize that the Other’s needs and desires reflect oneself and not the lover’s.

Finally, it is curious to observe that, in response to the Freudian adagio “What a woman wants?” Patrice Chéreau responds with his Gabrielle, by attesting that what a woman wants is not to be revealed. Mystery is at the essence of the female character’s most profound wishes. Love appears to be one transgression that Gabrielle concedes momentarily to her own transformation into an unveiling of her personality, but again, as she rapidly discovers, it refers to a transformation underneath the skin of a mistake.

Bibiography

Gabrielle (Patrice Chéreau, 2006).

Conrad, Joseph. The Return. Foreword by Colm Tóibín. London: Hesperus Classics, 2004.

Gondek, Hans-Dieter. “Cogito and Separation : Lacan / Levinas.” Levinas and Lacan. The Missed Encounter. Ed. and Intro. Sarah Harasym. Albany : State U of New York Press, 1998. (22 – 55).

Lacan. Séminaire. Livre XX. Encore. Paris: Seuil, Coll. Points Essais. 398.1975.

—-. The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. Book XI. Ed. Jacques-Alain Miller. Trans. Alan Sheridan. NY: W.W. Norton, 1998.

Lévinas, Emmanuel and Jacques Lacan. The Missed Encounter. Ed. Sarah Harasym. Albany: State U of New York P, 1998.

Peperzak, Adriaan. Ed. Bernasconi, Robert. “Only the Persecuted: Language of the Oppressor, Language of the Oppressed.” Ethics as First Philosophy.The Significance of Emmanuel Levinas for Philosophy, Literature, and Religion. New York: Routledge, 1995. (77-86).

Sarup, Madan. An Introductory Guide to Post-Structuralism and Postmodernism. “Lacan and Psychoanalysis”. Athens: The U of Georgia P, 1995. (5- 29).

Zizek Slavoj. How to Read Lacan. NY: W.W. Nortong, 2006. (10).

—-. Looking Awry. An Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1992.

Zizek, Slavoj and Renata Salecl. Eds. Gaze and Voice as Love Objects. Durham: Duke U P, 1996.

—-. La Subjectivité à venir. Essais critiques. Paris: Editions Flammarion, 2006.

Notes

- In English, meaning successful. All subsequent translations within the text are by the author. ↩

- The fundamental notions of the Lacanian triad real, symbolic, and imaginary, are reviewed and explained by Zizek in his How to Read Lacan in terms of a game: “For Lacan, the reality of human beings is constituted by three intertangled levels: the Symbolic, the Imaginary, and the Real. This triad can be nicely illustrated by the game of chess. The rules one has to follow in order to play it are its symbolic dimension: from the purely formal symbolic standpoint, ‘knight’ is defined only by the moves this figure can make. This level is clearly different from the imaginary one, namely the way in which different pieces are shaped and characterized by their names (king, queen, knight), and it is easy to envision a game with the same rules, but with a ‘different imaginary,’ in which this figure would be called ‘messenger’ or ‘runner’. Finally, the real is the entire complex set of contingent circumstances that affect the course of the game: the intelligence of the players, the unpredictable intrusions that may disconcert one player or directly cut the game short.” (8-9). ↩

- Secondly, love is therefore an inherently historical phenomenon: its concrete configurations are so many (ultimately failed) attempts to gentrify, tame, symbolize, the “unhistorical” traumatic kernel of jouissance that makes the object unbearable. Thirdly, love is never “just love” but always the screen, the field, on which the battles for power and domination are fought. Is voice, as a catalyst of love, not the medium of hypnotic power par excellence, the medium of disarming the other’s protective shield, of gaining direct control over him or her and submitting him or her to our will? Is gaze not the medium to control (in the guise of the inspecting gaze) as well as of the fascination that entices the other into submission (in the guise of the subject’s gaze bewitched by the spectacle of power?) (Zizek, Gaze and Voice as Love Objects, Introduction, 3). ↩