Interview with the Kuchar Bros

Bronx-born underground and avant-garde film luminaries The Kuchar Bros have been tirelessly making super-8, 16mm films, and video on their own terms since the 50’s and continue to do so to this day, together amassing an enormous and impressive body of work. Twins George and Mike are most famous for movies characterized by casts made up of neighbourhood friends without any acting abilities traipsing through a comic-book color palette of cardboard sets and garish lighting, adorned in exaggerated makeup and spouting lines off obvious cue-cards in a deliberately overwrought manner over stolen b-movie soundtracks, the intensely personal and poetic nature of the subject matter transcending any amateurism. Any hilarity played dead straight. Some of their lesser known works are more experimental in nature; sentimental and even sombre contemplations on (predominantly male) physique, bucolic locales, video diaries about the weather, and slices-of-life showcasing their artist friends.

They’ve worked separately and in collaboration, both behind the camera and in front of it, practically originating the camp aesthetic rubbing shoulders with the likes of Kenneth Anger and Andy Warhol in the 60’s heyday of NYC underground film. With lurid titles like Hold Me While I’m Naked, Lust for Ecstasy, Sins of the Fleshapoids, and Eclipse of the Sun Virgin, their work has had a far-reaching influence on such icons as Roger Vadim, David Lynch, John Waters and a slew of undergrounders still struggling to this day, with the Kuchars’ staunch zero-budget DIY approach being a strong inspiration.

The Kuchars weren’t only pioneers in underground film but comix as well, cross-pollinating within the underground comix counterculture scene of the 70’s, occasionally casting some of the artists themselves in their films. Their own comix artwork has appeared in several anthologies, espousing similar sensibilities as their movies, and as far back as 1965, Sins of the Fleshapoids for instance mixed mediums by introducing actual cartoon speech balloons within the frame emanating from its characters to depict dialog. This connection was of special interest to me, seeing as how my own work both in comix and film shows evidence of having followed in their footsteps, whether I realized it or not.

George presently teaches at the San Francisco Art Institute while Mike awaits his next muse. Preceding a rare phenomenal retrospective of their work at the Cinémathèque Québécoise last November through December of 2007, I had an opportunity to interview Mike via phone and George via email.

Mike Kuchar Interview Via Phone (November 16, 2007):

Rick Trembles: How are you?

Mike Kuchar: Yeah I’m ok; I enjoyed your comic very much. I love when you load the page up with all those convoluted curlicues and scribbles; it’s really something, quite a rising spectacle. (To view some Rick Trembles’ comics, such as the “Motion Picture Purgatory” series, click here, then click on “Archives” to access past Motion Picture Purgatory reviews).

Rick: They can be kind of text-heavy sometimes.

Mike: Yeah there’s a lot of energy.

Rick: Thanks, yeah so far I’ve tackled 3 films that are Kuchar-related as Motion Picture Purgatory comic strip reviews, Screamplay, Sins of the Fleshapoids and Thundercrack.

Mike: Oh yes, now Thundercrack, that’s something my brother George wrote for what’s his name, a student of his…

Rick: Curt McDowell?

Mike: Yeah right, he went on to make pictures. Yeah, he did them one by one; he sort of spilled out of the closet. He was an interesting person. He let it all hang out, literally, you know? He was a first rate sex-fiend. I mean that in a good way.

Rick: Is there anything comparable to that kind of sensibility these days?

Mike: That was another era. Anything goes. No, not anything goes but a very permissive and loose era, yeah. Even in the schools. It’s interesting, it used to be that it wouldn’t be considered outrageous if a student had the urge to jump into the pond or fountain, sometimes just get up on campus and just sort of shed their clothes and sort of just enjoy it.

Rick: The sexual revolution.

Mike: It was different. And you know, I don’t know what it is, times change and attitudes change, they fluctuate. They go back and forth. I’m rambling, what am I doing? You wanted to ask me a question (laughs).

Rick: Oh no…

Mike: And as for Screamplay, that’s the one George acted in. Yeah, that was a friend he had, I don’t know where he met that guy. They became friends and…

Rick: Rufus Butler Ceder (director of Screamplay).

Mike: George went up to Boston to shoot that and the director, he was married to this woman, although they are no longer together. It was a bitter break-up. She was bitter about it, but he wasn’t, he was a kind of a flexible fellow. She was an actress and was the lead lady in Screamplay. Unfortunately during the production they had a lot of wires set up on the floor to light the set and my brother was doing a scene, and in the scene he has to back up and he backed up into the wires and fractured his ankle in a very, very bad way. They had to rush him to the hospital for a ten thousand dollar operation.

Rick: Ouch, there goes most of the budget.

Mike: Probably all of it (laughter). That was one of those catastrophes on the set, but never on our sets. We never had any catastrophes, my brother and I. We never had that many wires on the floor (laughs). Maximum was probably three lights. Three of those clamp lights with those kind of metal hooks or whatever, none of those high-priced lights. We were very low budget. Since we did all the technical stuff on our old pictures, my brother and I, it had to be enough we could carry without too much of a strain.

Rick: Which can be done nowadays, everything is so compact.

Mike: Yeah right. Well I’m kind of an old man now. I can’t carry all those heavy cameras anymore. 16mm cameras, they’re all metal and all those other things. Video cameras, they’re all lightweight, for the most part plastic or whatever. As long as it gets projected on the screen and it moves and makes noise.

Rick: For sure.

Mike: That’s what matters.

Rick: I’ve noticed in some of your earlier films you had some very impressive special effects, even though they have a homemade look, but you were doing matte paintings and miniatures. How do you feel about the current, less tactile computer generated imagery in today’s films?

Mike: Oh, I enjoy it but it seems that’s the star of the picture, the technical department. Well you know, Hollywood basically deals with spectacle. I used to see those 20th Century Fox spectacles in the 1950’s when they came out with costumes and sets, and the idea was to give the audience a spectacle. Now they’re manufacturing it, it’s all artificial, computers are bringing it together, it’s good. Sometimes it’s the only saving grace. I enjoy it. Yeah, I like science fiction and I think computer animation is ideal for that, it works well with it.

Rick: Have you ever ventured into that territory? Computer generated special effects? With the more tactile stuff you could do it with stuff that was still under the kitchen sink.

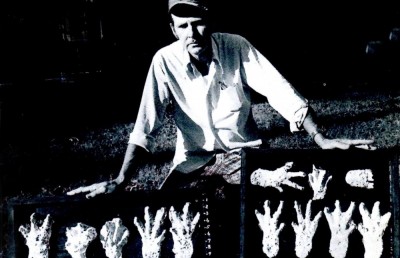

Mike: I guess I’m more interested in people or fleshiness, I like more flesh stuff (laughs). I don’t have a computer, my brother has a laptop. I do like drawing, I always used to draw, and you know I did comic books too. When it came time to go to high school the teachers in public school said, well, you could draw, you got a certain talent and you got two choices of schools in New York: the fine art one that was called music and art, and the commercial art one. So I said, I’ll go to the commercial art because fine arts artists always starve at the beginning. At least half the day was devoted to that, you made a portfolio and then went out and pounded the pavement and got a job in the commercial art field. But I was always interested in drawing and painting and so when it came time to make pictures I would use that ability to make backdrops or matte paintings. A lot of them I did with pastels, it was easier to work and blend. So yeah I would incorporate that into my pictures. And when you film it, you create an illusion and you can do it expensively or inexpensively, it’s all an illusion and we would try out these ideas with overlapping and doing in-the-camera special effects which I actually enjoyed. It was risky but sometimes it’d turn out better than you’d think. It comes together and creates a kind of an illusion. Also, the discipline is good; you have to regiment yourself. Doing it in the camera you have to rewind the film back to wherever you want it to happen but it was good discipline.

Rick: Very suspenseful, you never know what you’re going to get until you get it.

Mike: You have an idea but sometimes it even turns out better. You get an idea and then you try it out and then things happen and then the combination sometimes surprises you, it turns out even better. The whole idea is to put on a magic act.

Rick: Sleight of hand.

Mike: Yeah.

Rick: I used to love looking for matte lines in, you know, those Ray Harryhausen epics. I used to try and find the matte lines.

Mike: Yeah, sometimes you could see them.

Rick: But he would use sleight of hand. He’d deliberately put some action somewhere else so you wouldn’t look at the mattes lines.

Mike: Yeah, I always admired his pictures.

Rick: Yeah, he’s a hero of mine. Speaking of the artwork with the comix and everything, I’ve seen some of your more hardcore work in the book Funeral Party.

Mike: Oh yeah, that’s a little spooky. You know what it was? I was doing some kind of underground comics, and I got typecast into doing sexy stuff, because a friend of mine, a roommate who wrote for this guy, he was putting out these comic books, it was a homo title, Gay Heartthrobs. And they needed an illustrator to do their latest issue, the issue was pretty bad, they had no feel for it, but anyway I did a couple of samples for them and they loved it. So I did three stories that went out. You do something and it gets printed and circulated, then editors of other sexy publications saw it and would give me a call. I didn’t advertise it, they’d just send me stories to illustrate; so it got me back into drawing and gave me some pocket money too, so I wasn’t feeling guilty sitting there drawing, the hours going by, saying “what am I doing”? You know, I had rent to pay (laughs). So that got me back into drawing. Then there was an art show in Los Angeles, actually a sex club was putting on a homoerotic art exhibit. It was an interesting gallery setup. Well, the gallery opened at 10 o’clock at night and stayed open until 6 in the morning (laughs), and there were mattresses and throw-pillows on the floor, under the paintings by the way, which were really excellent. There was a big variety of illustrators who do that type of work and it was quite a show for the audience. So if the work turned on the customers, people who came into the show, they could actually have sex under the painting (laughs). Which is a very interesting gallery situation, I rather liked it. This was in the very early 70’s. Like I said this was another era.

Rick: Era of the orgies.

Mike: I liked some of the other illustrators, and one guy whose work I liked, he could never get it shown because it was too visceral, it scared the shit out of the pansies (laughs), but anyway I really admired his work. I thought they were symbolic representations of lust and body fluids, and then we got in a correspondence and we began to send each other drawings just to compete with each other, just to have fun. It was scary, but not scary. I’m a gentle person, but somehow I was inspired, and then that guy who put out Funeral Party liked that type of work so he included it in his book. Yeah it’s a little spooky. It’s a long time ago. This was a mental thing I had going with this guy. I look at it now and they’re sort of a little icky for me.

Rick: It’s not indicative of your films.

Mike: It edgier stuff. You know, it’s a little scary or it could be interpreted wrong.

Rick: I find it more humorous than scary.

Mike: Good, yeah well there’s a camp element in all of my stuff. I’m a product of pop culture, I mean comic books and movie posters and double features, that’s where I grew up, so it’s all a regurgitation and a reinterpretation. I’m not sure what you’d call it, that kind of presentation. But it gets mutated along the way.

Rick: Do you have any thoughts on how this aesthetic has evolved or mutated over the years actually? You know, the current state of camp?

Mike: Sometimes I think it’s mistake to go at something saying, “oh, this is going to be campy,” whether it’s the plot or whatever, you know. Don’t be too conscious of it. I don’t know if you remember, but there was always makeup, especially on the ladies, but I’d tend to go overboard with that and then sometimes people would have their own musical scenes whenever they appear, the music would get turned up.

Rick: Their own theme music.

Mike: Yeah, at certain episodes of the picture, like it’s dramatic or something, all of a sudden you pour on the music. I would do that, but it would somehow be a little too loud or just obvious. I find the campy movies were the ones that didn’t intend to be camp or didn’t intend to be funny.

Rick: For sure.

Mike: Because they were so preposterous with the stories and yet, you know, the actors, they did it because it was part of the plot. But then seeing it, it was so absurd, but no matter what, movies are fake, they’re just manufactured. There’s people acting, well paid people playing poor people, etc., so the whole process is artificial. The reason why the picture is made, that’s the reality, that’s what’s real. Like the reason or the attitude toward it, toward making it, that’s the real thing: Why was it made? In some cases, what is it trying to say? But the process is artificial, there’s camera angles, people in costumes, etc. I guess the relation to camp is that sometimes if you see the artificiality of it, it doesn’t matter, and that’s ok, because it’s just pointing out that particular reality, that it’s an artificial process. Sometimes it’s seeing the floors, sometimes it’s seeing the lights move. It’s reassuring. It’s not this slick and polished look that makes it more alien or, not untouchable but just sort of slick; and seeing the rough edges, enjoying seeing the process that it is kind of fake or at least making pictures that would otherwise be spit upon, re-evaluated and enjoyed because they’re either so absurd or you could see that all that technical stuff wasn’t camouflaged, it’s endearing.

Rick: How do your films fall together? Are the results always exactly the way you’d envisioned or is there a lot of compromise involved?

Mike: Yeah, it’s an interesting process. You know, sometimes, often the case is you meet some people, they consent to being in your picture and there’s a certain quality about them and you say, “Now I can make the kind of picture that I wanted to make because these people, there’s something that they’re good at.” Each person has their own quality, they like to do certain things, and then you say, “I could make this kind of picture now because I met this person and I can get away with it,” or “because they would put up with it and do it.” And so in some ways it kind of falls together, all of a sudden it’s like the chemistry is right.

Rick: So there’s room for improvisation?

Mike: There’s also chance. I find it’s the feeling that starts the picture. You get a feeling of what this picture should be about and then the way of doing it is all optional. You arrive at the spot where you have to shoot and all of a sudden the light is coming through the windows in a certain way that you hadn’t expected and all of a sudden you say, “oh well we’re going to do the scene there or we’re going to do it here.” It’s the availability, or the way things present themselves. The pictures sort of start to make themselves. What’s really important is the feeling, or the atmosphere that you want and then you go search for it when you’ve got the camera there and the people there. You have to work them to get what you need with them, while knowing that they are not perfect. Well neither am I, but how do you use them if they’re not very good actors? You light them in a certain way and then you dress them a certain way. The image has a certain feeling about it, and helps to make your acting look better, or makes them look depressed or dramatic or whatever and you deal with them that way. And as far as compromising, when you make your own pictures you’re the complete boss, you don’t have to answer to anybody. Except for the people who consent to be in it. I’m the complete technician, I do all the camera angles, and I do all the lighting. I take it all through the editing. I do that because filmmaking is a very interesting process, it’s got all these stages to help push the picture in the direction you want. And I know at a gut level where it should go or if it’s working or not.

Rick: You get the final say.

Mike: Yeah, sometimes it’s hard for me to explain what I want and sometimes I’m not even quite sure. These pictures, they’re never written beforehand. If I knew what the endings would be or how complete they would be I’d have no interest in making them. I have to make them to come to a conclusion, it’s like, subconscious. My motivation for why I make the picture could be the people in it, that they inspire me, or give me opportunities. Sometimes that’s the incentive to get a picture going. Sometimes, it’s a place that sort of haunts me or has a certain appeal and you want to shoot there; that’s the initial inspiration for the picture. Then I start to do things, but there are reasons behind the actions, they’re not overt, they’re subconscious. Then I begin to sense what this is about, and I get more and more involved in it. I’m building it as I’m doing it, then there comes the time where I see the structure, whether it’s a plot or not, and then I find the end, where I can’t go on anymore and I’ve got to complete the thing. I don’t have to explain the scripts to anybody, sometimes I can’t because I’m finding out what it’s about myself (laughs). It depends on the kind of picture. What the picture is going to be about depends on my mood, but I don’t have to compromise with anything. I use my own judgement, editorial or content-wise, on whether or not I think a scene is appropriate. For example, in Sins of the Fleshapoids, it depends on my mood. People said, “Yeah I like your movies, I’ll be in your picture, but I’d like to do a certain thing.” Like there’s this one woman who pours water on the robot and then the robot gets mad and rips her dress off. That was required. She said “I’ll be in your picture but I have to take a bubble bath, you have to have me taking a bubble bath or else I get my clothes ripped off.” Fine. So I wrote those scenes in, she wasn’t in a bubble bath but she got her clothes ripped off. It was part of the persona that she wanted to project; she was interested in being a glamorous Gina Lollabrigida type. And so you had to be flexible and incorporate the things that they want to do, but that’s fine with me, I could easily do that. In some ways the compromise is that you work with people but they’re good at something in particular, and you just write that into the script. Sometimes when people are a problem you figure out how to get rid of them even though they were supposed to be in the rest of the movie, you have to find a way get them out, get rid of them. I tend not to use people I don’t know. People have to know me or I have to be introduced to them and I have to feel certain vibes and they have to understand me, that I don’t have much money, I can’t pay them. But I work fast and I do make dinners afterwards, you know we try to make the whole experience interesting.

Rick: A social event.

Mike: Yeah it’s like a party, like a film party. Then they get the chance to see themselves up on the screen where it can give them some pleasure.

Rick: With the comix, I read somewhere that you had Mike Diana in one of your films (underground cartoonist arrested in Florida for his controversial art).

Mike: Yeah that’s right; I have him in a couple of pictures.

Rick: He’s very photogenic, I’ve seen pictures. But I haven’t seen the films that he was in.

Mike: Oh, yes, well I could always send you some, I don’t know, you got a DVD player? Yeah, he was a nice fellow. He’s good for a certain kind of picture, and at that time he had a kind of a physical appearance…

Rick He looked like a beach bum.

Mike: Uh yeah, beefcake. So I would make pictures that featured that. And we had something in common; we both drew comic books. I saw him lately, I hadn’t seen him in years and I saw him a couple of months ago in New York a few times. It was good to catch up with him. The years have made him very warm, and he continues to draw, he brought all his sketchbooks.

Rick: Yeah I’m a fan of his too.

Mike: Yes he’s a nice fellow, very easy going.

Rick: John Waters said that after seeing your films he went home and created Divine and started making movies.

Mike: You know the real story with that is he would go see our pictures but he was making movies too, but our pictures gave him that additional charge; or they were inspiring and when you see something that inspires you or gets you excited you just go at your own work with even more intensity. So that’s basically it, because you know, he was making his pictures; he’s a few years younger. It just revitalized him. I mean, he enjoyed the pictures and it gave him that little extra boost or fortitude to continue his intense enthusiasm for pictures. I remember he told me that, the first time I met him, we’d get together in California and he told me. So that’s basically the story of that. The similarity is that he’s interested in people and characters, and my brother and I, we’re interested in people and characters too. We went to the premiere of Divine Trash, the documentary about John Waters making pictures in Baltimore, and Divine’s mother was there, this is after Divine had passed away. She’s a very domestic kind of lady living in Florida and I always sensed an insecurity about her son, like she gave birth to a monster or something (laughs). But then there was this museum, The Museum of Visionary Art. The curator, she took all of us to the museum and in the lobby there was this huge statue of Divine in that red gown with the flaring bottom. It is a very nice museum and we were having dinner there and Divine’s mother was there, and when she saw her son like an idol, an icon accepted and appreciated by the public, she sort of accepted that, like no matter what, he’s something special. Tears came to her eyes. Here’s this son that she probably had great doubts about all her life (laughs) and then here he is, this big idol built up as a kind of icon for a whole new generation to emulate or appreciate for what he contributed, as an image or as an attitude. She saw it, and it was a very profound acceptance. I had a friend who used him in a picture. I never met the man, Divine, but he played a man, a detective in this film and it didn’t work. It was a picture about call girls, a serial killer picture. I always thought Divine should’ve played a call girl (laughs). He played a man and you know it wasn’t convincing.

Rick: Do you have any favourite current contemporary films?

Mike: Well I got nothing against them. I saw Dragon Wars, only because I like dragons, I like B-movies, I like monsters. I used to watch all those Godzilla pictures, monsters rampaging through the city. And I enjoyed it, it was like a comic book. It was junk but it was good, you know when the monsters came on it was terrific.

Rick: I’m a sucker for a good monster.

Mike: And the cast is like, the bit players, I’ve never seen any of them before but that’s ok because I like those kinds of pictures. I don’t know, it’s strange but in the past I would always look at the newspaper and I’d look and see the worst possible titles and go “Ooh, I got to see this.” I would go in the afternoon in the Bronx and usually there were only maybe a few truck drivers in the audience or some bag ladies plucking chickens in a shopping bag or some teenagers playing hooky and then I would see these pictures…they were like strange events. You know what it was? It was like…you know that thing about something being naughty that you shouldn’t see, it makes it sort of attractive. There was also something sexual about it, like voyeuristic or bawdy that you shouldn’t see. But I always liked low budget pictures because they’re more gritty and real and they’re with actors who aren’t that polished and you can see their humanity or their vulnerabilities (laughs). It’s more evident.

Rick: So much of that stuff is being dug up now and being put on DVD.

Mike: Oh yeah, it’s appreciated.

Rick: Like all the 42nd street grindhouse stuff. I love that stuff.

Mike: That’s right. I think the pictures are just unusual for various reasons. They could become considered masterpieces or have great followings or be re-evaluated and admired.

Rick: They’re like documentaries, all the original locales long gone, it’s history. Did you happen to see Quentin Tarantino’s movie Grindhouse that came out recently?

Mike: No I haven’t.

Rick: It’s so peculiar because they spent millions on special effects to make the film look scratchy and old.

Mike: Yeah somebody told me, somebody less informed, they thought, “Hey, how can you show such a bad chopped-up print?”

Rick: Oh it was a total flop because of that very reason. People actually bought the fake blemishes hook line and sinker.

Mike: I guess you have to have age behind you too. You know the approach and the concept and the whole thing, knowing about film itself and theatres and projectors. Yeah, but a lot of these young people they have no sense of that, they just grow up with television.

Rick: It’s something to see though, all these professional actors deliberately trying to act like they’re bad actors in a b-movie.

Mike: Yeah, isn’t that something? It’s interesting how all of a sudden there’s an attitude about pictures that originally weren’t worthy of spitting on, now in a way, it’s sort of re-evaluated and appreciated. I knew that singer who’s in that punk band; what do you call it, punk rock, “The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black” (Kembra Pfahler).

Rick: Oh yeah.

Mike: She got that title from me. She liked my pictures, she always liked my movies so she put on a performance and I happened to be there because I was a projectionist and she came over after and said “What did you think, what did you think?” I was kind of tongue-tied and I didn’t know what to say so I said well it was a night of voluptuous horror and she said, “Can I quote you on that?” I said of course. She used that title. I put her in a couple of pictures; she was very good.

Rick: Very photogenic.

Mike: Yes, and she made me very, very comfortable. You know, I had called her and I said “Kembra I have an idea maybe for a picture,” so I’m just testing the waters, I said “You want to be in one?” She said “Well Mike, yes but it has to be lewd and nude.” All of a sudden I felt so relieved, I mean, I felt like I could express myself, you know what I mean? All of a sudden you don’t feel uptight, like, “Oh well, can I do this?” Or if the scene calls for something, how am I going to break it to the person. It makes you feel so relaxed and it gives you such leeway. Uh, yeah, it’s very, very nice in that way. She made me feel totally relaxed. Sometimes you use strangers, but I never audition. For one thing, I think it’s a horrible thing, I mean for me it’s like a meat market. I mean who am I to judge? Also, I can’t pay them; I don’t have the money to pay them. I have trouble paying the rent, my own rent (laughs). But then why would anybody want to be in one of my pictures? But actually, you know, they do that, they’ll even do it for nothing. But again I have to have a rapport or they have to understand me. I have to feel comfortable with them also because a lot of the pictures, they’re really about me, and I have to feel in a way that I can express myself and use them and be comfortable without feeling embarrassed. But anyway, if you use strangers, what happens is you might tell them to do something and they say why are you asking me to do this? Or then they start getting suspicious. Once my brother was asked to do a documentary on this sculptress and they sat around and he said “Well you know what? Sit down here and put a little something in the glass and sit there” because it just happened to look nice, it gave her something to hold onto and she said, “What are you trying to do, make me look like a drunk?” You know what I mean? If you get people who really don’t get a sense of you, then they get suspicious. You ask them to do something and then they think “What does this mean or what is he trying to do?” Also I couldn’t work in a crew situation. I like doing the process of picture-making myself, but I wouldn’t want to work with a crew of strangers. Sometimes it just seems like since it’s personally motivated by me, I can never put myself in the pictures physically, they’re about me but I just do it with the people in front of the camera. They sort of represent all those kinds of drives in me, libido, whatever, I work it out with them. If I put myself in the film, it would make me sick because the pictures are already about myself. But I would feel restricted to have strangers standing there watching what I’m doing with the people in front of the camera.

Rick: Even though ultimately it ends up being viewed by strangers.

Mike: Yeah but that’s ok, because by then the stuff is not the same, it’s finished, but just the making of it which is a different kind of thing.

Rick: Does a lot end up on the cutting room floor?

Mike: Usually my ratio is that two thirds winds up on the cutting room floor. You know what it is, you go out and you make a picture, you know the feeling that you want and then you have to get it and there’s various things that present themselves, or obstacles, and you just have to figure ways around it. Sometimes it’s like a battlefield and then in the editing process you gather all the material and then you get the gold out of all that ore. But you can’t really think too much and plan and storyboard and have the whole thing figured out in your head because when it comes time, you have to deal with reality. You have to deal with the weather; you have to deal with the time limits. So you have to allow for that, and what really matters is the motivation: What’s the reason that you’re making this thing? Once that becomes clear, then everything else is flexible, you just have to work with what’s there and figure out how to say the same thing or how to express the same thing. It’s the feeling that sort of dictates, and now you have to deal with reality to get to the essence of what the picture’s about. You have to keep your eyes open and figure out all your options and sometimes rethink things. Sometimes you have to rewrite, but it will say the same thing but in another way.

Rick: So it’s a very improvisational approach, stream of consciousness.

Mike: Yeah and how you attack the necessary shots. Sometimes with people you have to figure out how to do it and if it seems off key maybe you do it another way, but I do leave it open. So yeah, it’s matter of being flexible.

Rick: Your dialog’s very theatrical. Is it all written ahead of time?

Mike: Yes, I have an attitude towards that. If I’m going to write or have people say words –and I don’t know, maybe this is that camp thing– but I always appreciated movies where the writing was very obviously written, like the words were structured in certain way, not like the way we normally talk but very literal, literate, do you know?

Rick: Absolutely, that’s what makes it larger than life in your films.

Mike: But what it is, it’s actually tackling words and hearing the rhythm of it, and being so precise or else having a certain flavour, like “ooh, I know that writer?”

Rick: It’s musical.

Mike: I always admired it. I did a whole series of teleplays, a lot of them were done in video. I got into writing because now I don’t have a synch sound 16mm camera, so I didn’t make very many synch sound 16mm pictures. I had a friend who had a synch sound camera so I would use it when he was free; but now with video I had all immediate synch sound so then I got into writing but I would always really labour over the writing and try to express myself. You know, if I want to hear the way we always talk I could go hear it on the subway train. Why do I want to listen to that? Or hear it on the street. Why do I want to put it in a movie and hear the same crap? No, I’m more conscious of writing. The script is written. Dialog is written, it’s given to people to recite (laughs). I’m conscious of that and I like that and it’s deliberately written but it’s expressing something. But you also have to point out that yeah, it is written.

Rick: That’s the one thing you do have complete control over.

Mike: Yes.

Rick: Like the weather won’t affect that.

Mike: No. You know, a lot of these people, they’re not really actors. Actors like to memorize lines. They’re good at that, but often I don’t use them. Every once in a while an actor wants to be in my picture and they like to memorize stuff but otherwise I used to make cards and place them on the walls or I would even paste them on the face of the person they’re talking to who has their back towards the camera so they’d be able to look at their face and read the lines. But you have to do that because you can’t turn this into hard work for a person who’s donating their time and they’re not actors. You don’t want to make it an ordeal because there will be a mutiny. One day they won’t show up; they’ll just say “this work is tedious.” It’s too much work to memorize lines so you have to figure out all kinds of things, like pasting dialog on people’s heads, as long as they say the words. And I laboured over the words, so they have to say every word because I laboured over it. And I guess part of the enjoyment would be the wording of what they say and it’s not like, to me that’s what makes it art, or might make the actors memorable. What makes it art is because it is spoken but it is not street talk. It is obviously written but it’s written for a purpose and it’s dialog, and I mean dialog literally. But I do like pictures where I can appreciate the dialog were somebody actually laboured over it and it’s completely written.

Rick: It’s got to be captivating.

Mike: Yes, I just like that. Again, I guess it’s that kind of camp attitude. Well, no, it’s not camp because, it’s important, but you know, it’s all part of the moviemaking process, writers, dialog, people reciting words and the words are meant to express a story and all that. If I want to hear all that realistic talk I’ll just go out on the street. You hear so much of that now you just want to throw up and they just keep repeating the same thing, putting words in for other words they can’t come up with, so they just put the crudest words in-between. I don’t care. If I want to hear that I’ll just go out on the street, not sit in a movie theatre.

Rick: It could have the hugest budget and the most special effects in the world but if it’s badly written you don’t want to listen to it anyways.

Mike: Yeah, you can hear the same kind of thing outside.

Rick: Do you have any projects lined up?

Mike: Not at the moment.

Rick: Are you teaching now?

Mike: My brother is. Once in a while I do a semester or two here and there but I haven’t done that lately. I used to get jobs as a cinematographer for other people’s fiascos. Because they would call me and say they liked my work on my pictures, they way I’d shot them. They would be paying jobs but I don’t do that anymore because I never really liked being on other people’s sets. I thought they were just mean and frantic and I always thought trying to be creative should be a celebration or a party, but on those sets they just have people humiliating themselves and being indecisive. A lot of those people I have no idea how they ever got money because they don’t know how to deal with people. You may as well throw the money out the window.

Rick: But you have none lined up of your own?

Mike: Inspirations will come.

Rick: Depends on the people, right? You’ve got to find the people. Do you actually find yourself looking for people anywhere?

Mike: I don’t overtly look but you know when they come. Sometimes you start a project and I don’t know, psychically you start meeting people, you know what I’m saying? You talk with them or they have seen your pictures and you say, “This person, I need someone like this in this latest picture.” I’m in-between but you know, inspiration will come. Or sometimes somebody will call and say let’s make a picture. We haven’t done it in a while and it’s a wakeup call and it starts me thinking. But uh, yeah, that’s the way it is.

Rick: Well I hope there’s more to come.

Mike: Oh, there will be. It’s my hobby and my vocation.

Rick: You got to keep it a hobby.

Mike: Yeah it’s my vocation. I’m always interested and I’ll always be doing it. Many times it serves as a hobby too. Keeps me occupied because you have to work these things out. Go through all these stages. It’s very captivating.

Rick: I watched your teleplay Stranger in Apartment 9F last night and I was laughing out loud, it was great.

Mike: Yeah, that’s got some good characters in it. Yeah, the lady comes in; she mistakes this guy’s kindness and falls in love with him. She’s been in a whole series of pictures, she became a devoted person.

Rick: I don’t know if any of the Mike Diana stuff is on the bill coming up at this retrospective but I’d like to see some of that sometime.

Mike: Ok, he did one called Statue in the Park, then On a Shore Beneath the Sky. In that one I gave him a leading lady but it was actually a man, it was a sex change (laughs). Leading lady was a man, no longer a man, this glamorous woman.

Rick: Is Kembra in those too? They were an item for a while weren’t they, Kembra and Mike Diana?

Mike: I think so. Actually, she’s the one who introduced him to me. She wanted me to do a kind of promo on her band and he was a fan of hers and he was in town so he came in and we did a few things together. That one was called Blue Banshee; it was about her and her band. She wanted me to do it. She liked my work. Funny thing is, after I shot it, I said I can’t use her music; it would spoil the images (laughs). So I used other kinds of music. She liked the picture, and Mike Diana’s in that. I didn’t want to tell him that his lead lady was a man but my brother, he’s kind of devilish so he sort of let that slip, but then Mike Diana rather liked the idea because he’s kind of off key.

Rick: They’ve been in some Nick Zedd (NYC underground filmmaker) stuff too haven’t they? I’ve seen Kembra in some Nick Zedd stuff.

Mike: I don’t know, maybe. He was available a few years ago. I think he was.

Rick: Have you seen some of Nick Zedd’s latest stuff, “Electra Elf”? The TV show?

Mike: They’re like, kung fu superhero stuff.

Rick: Yeah and they’re doing the special effects and everything. It’s pretty funny.

Mike: Yeah with the blue screen. They have a lot of energy, with the fight scenes. He’s really into it.

Rick: You should get a TV show like that or something.

Mike: That’s right.

Rick: Hey one last question, I don’t know, I mean this is a long shot, but as far as underground comix are concerned, you know, like the 70’s stuff, I know that your brother George was drawing for Arcade Magazine back then and there was a lot of cross-pollination going on, Art Spiegelman and Bill Griffith were in some of his movies. But there was another cartoonist named Rory Hayes, are you familiar with him?

Mike: Yes I met him a few times. He was a friend with a guy who owns a comic book store.

Rick: Gary Arlington?

Mike: Yeah that’s right. And I would see Gary often. I was visiting the store, I went over to his house one time and Rory was actually roommating with him for a while.

Rick: Apparently he made his own homemade super-8 horror movies.

Mike: Rory? Oh, I didn’t know that.

Rick: Oh yeah, Griffith did a comic strip biography on him and he said that in it, he shows him aiming a super-8 camera around. I’ve been dying to see what the results were of his movies.

Mike: Oh yes, you know Gary, his store is no longer around. I hope he didn’t pass away. I hope he’s ok. He’s probably in his late 60’s. I hope he’s alright. But his store’s no longer there. I haven’t seen him around. Yeah I went over to visit them at Gary’s place. Rory was there and he told me a story; he was at a party and Janis Joplin came over to him and said “You disgusting little… how could you draw such horrible things?”

Rick: She said that to Rory?

Mike: Yeah, she was lambasting him at a party, just talking about how disgraceful his attitude towards women was. She was just lambasting him. But I said don’t feel bad, the woman’s dead, she killed herself, she overdosed, so who’s worse, who’s more worse off and loused up? Don’t feel bad (laughs). But I remember she humiliated him at the party. She was no angel herself, you know? So who’s she to criticize?

Rick: Well people are digging that stuff up more these days, I think there’s a book that’s supposed to be coming out on all of Rory Hayes’ stuff.

Mike: Oh, interesting. He was a soft-spoken fellow.

Rick: Yeah he got all his demons out in his comix.

Mike: Yeah, same thing with Mike Diana.

Rick: Yeah there are some similarities.

Mike: You look at this stuff and you go ok, it’s kind of scary, you think what’s this guy like? Is he an ex-con or something? But then you meet him and he’s so mild-mannered and sweet and gentle. And I guess some of that stuff, when he was a teenager, you know teenagers, they sometimes throw bricks through windows or whatever. He didn’t do that he just expressed himself through his comic books. Oh, and I asked him, I said “When you do these kinds of stories are they also a metaphor for sexual stuff or whatever?” He said, “No not at all.” He said the TV used to be on and then he’d hear all these newscasts about all these murders, dead bodies found and barbequed kids, abductions and whatever. It really hurt him and affected him. I don’t know what it did, but he regurgitated it. His defence against it was to just sort of wallow in it. All that kind of stuff and the way it would be publicized on the front pages on the newscasts. All these sordid horrible things that were just freaky and that affected him psychologically, it sort of came out almost like a defence mechanism, just vomiting it back out. Because sometimes, you know that kind of stuff, it’s like kinky or kinky manifestations, but in his case it wasn’t. It was a regurgitation of all that horrible stuff that was fed nightly on the newscast.

Rick: Yeah he’s got good comic timing. I’ve read a lot of his comix and as horrendous as they are I do manage to laugh out loud once in a while because they’re so ridiculous.

Mike: Yeah.

Rick: And he draws good monsters too.

Mike: Very good.

Rick: Yeah, he’s got a good imagination for monsters.

Mike: Yeah, his style lends well.

George Kuchar Interview Via Email (November 16, 2007):

Rick Trembles: How much of your initial vision remains intact percentage-wise in the end result of your films?

George Kuchar: I tend to think big and then just shoot what’s lying around to make the vision take shape. Hopefully the junk being used can be glamorized with lighting techniques and careful camera angles.

Rick: What do students enrolling in your film class generally aspire to? Does your curriculum ever burst any bubbles?

George: My bubble usually bursts when the class gets a look at what we created. The class aspires to whatever is supposed to happen in there.

Rick: Apparently you hooked up with the Frisco underground comix scene in the early 70’s. I’ve seen some of your work from Arcade Magazine and liked it. Which films of yours were fellow contributors to Arcade Magazine Art Spiegelman (“Maus”) and Bill Griffith (“Zippy the Pedigreed Pinhead”) in?

George: Art and Bill were featured in The Devil’s Cleavage.

Rick: Do you still draw comix or paint? Do you still read comix and do you have any favourites whether old or new?

George: I haven’t drawn for many decades except maybe to make a poster for some of our classroom productions. This summer three of my paintings from the 1970s were in a show at a New York gallery and one sold for $15,000!

Rick: Do you have any favourite current contemporary films?

George: I enjoyed Dragon Wars and also an Israeli movie about an Egyptian band that gets lost trying to find the venue they were scheduled to play at in Israel. I forget the name of that excellent film (ed., The Band’s Visit).

Rick: In earlier works you used to dabble in special effects, such as matte paintings and miniatures. How do you feel about the current, less tactile computer generated imagery in today’s films? I know that FX genius Ray (Seventh Voyage of Sinbad) Harryhausen for instance isn’t that impressed with CGI and rather likes it better when things don’t look too “realistic.”

George: My computer generated special effects don’t look real so there’s no problem there. I love inventing them though and experiment with what you can create with the software I bought. They pepper the class productions extensively and sometimes take over the plots (which is no loss as far as I’m concerned).

Rick: The likes of Ed (Glen or Glenda) Wood and the recently deceased Don (Alien Factor, Cinemagic Magazine) Dohler have been somewhat unfairly championed as the ultimate “bad” filmmakers although their efforts were sincere. Even if your aspirations were dissimilar, do you feel any shared kinship with such sensibilities?

George: Anyone who attempts to make their dreams visible via the moving image is akin to me regardless of the results. Ed Wood’s films are very well made studio pictures and look pretty good when seen in the 35mm format. They just look trashy on TV.

Rick: How did you hook up with Rufus Butler Seder? The artifice, expressionistic flavour, and homemade special effects of Screamplay share similarities to some of your early work. Did Seder ever admit to being influenced by the Kuchars? Have you been asked to act again lately?

George: I met him through a student who knew him and his group in Boston. Rufus and his dad and cinematographer, Dennis, were the lone visionaries of his style along with German cinema and the silents of yesteryear, I believe. I’m featured in a movie called, Three Days of Rain starring Peter Falk and a whole bunch of other stars plus I’ve got a short part in a film out on DVD called, Bong Water. I do a scene with Alicia Witt in a church setting. I played a bum.

Rick: You’ve said that massive amounts of money seem to make you uncomfortable but given carte blanche in today’s tinsel town, what would be your dream fantasy special effects flick to make with an unlimited budget?

George: We make them now at school with the lousy budgets allotted to my class. It’s down to $150 now.

Rick: What’s your favourite color?

George: The colors Kim Novak wore on screen.

For more material on the Kuchar Bros:

Camp Kings by Rick Trembles, in Mirror.

“The Day the Bronx Invaded Earth: The Life and Cinema of the Brothers Kuchar” by Jack Stevenson, in Bright Lights.

Sins of the Fleshapoids can now be purchased on DVD from the label Other Cinema. Trailer can be viewed on the site also.

And, don’t forget to visit Rick Trembles’ Snubdom.