Tradition and Modernity in Japanese Yakuza Films of the 1960s and 70s

The Nikkatsu Action films of the 1960s and Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles without Honour and Humanity series (1973-1974) present radically different portrayals of yakuza life. Both can be seen as attempts to create movies distinct from Toei Studio’s ninkyo eiga (“chivalry films”) that were very popular throughout the 1960s and offered a traditional view of the yakuza in particular and Japanese society in general. In contrast, the Nikkatsu films were flashily contemporary, heavily influenced by international films and its own recent series of “rebellious youth” movies, and celebrated aspects of modern Japan that the ninkyo eiga criticized. Fukasaku’s films reject the glamourization of the yakuza and visual stylishness identified with both of these sub-genres. Instead, it presents a rewriting of post-war Japanese history which exposes the fraudulence of yakuza mythology and adopts a deliberately raw film style to convey the chaotic nature of the period as well as the filmmaker’s political ideas.

Films featuring yakuza had been a staple of Japanese period dramas (jidaigeki) since the silent era. Toei films such as Theater of Life: Hishakaku (1963, Tadashi Sawashima) redefined the genre by updating the period setting to the Meiji (1868-1912), Taisho (1912-1926) or early Showa (pre-1941) eras and placing the action in big cities such as Tokyo (McDonald 174). These films were morality plays where heroes that were “the embodiments of valor and honor” and champions of traditional samurai values battled Westernized villains (Vick 44). Typically, a protagonist (invariably played by either Ken Takakura or Koji Tsuruta) would be forced to choose between obligation to his gang (giri) and friendship to a fellow gangster (ninjo), while the characters would be divided into good gangsters who followed the traditional yakuza code and bad gangsters who were only interested in money (McDonald 174). The climax would feature the hero armed only with a traditional katana sword slicing his way through a gang of bad yakuza with guns. As Tom Mes and Jasper Sharp write, “The ninkyo formula pitted tradition versus progress, and to offer Japanese audiences some respite from their increasingly Westernized surroundings, the former always won” (Mes and Sharp 44).

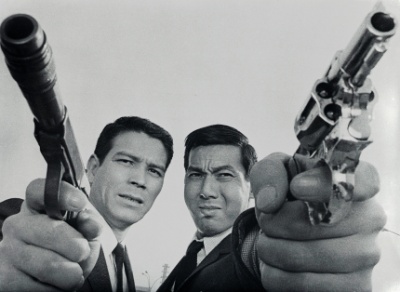

In contrast, the Nikkatsu Action films loved everything modern and Western. In Velvet Hustler (1967, Toshio Masuda), Goro (Tetsuya Watari) shoots at a gang boss from a flashy red convertible, while A Colt Is My Passport (1967, Takashi Nomura) features a coolly efficient hitman (Jo Shishido) using a rifle with a telescopic sight and having what at the time must have seemed the latest in fab gadgets, a radio telephone in his car. Probably the most extreme example is Tetsuya (Watari again) in Tokyo Drifter (1966, Seijun Suzuki), who wears a powder blue suit for much of the film, has a girlfriend who works in an art deco club where the locals go go dance to American-style pop music, and takes part in a punch-up in a saloon inexplicably transplanted from a Hollywood Western. While the heroes hold to the traditional codes of loyalty, they are identified with the new and modern and are invariably betrayed by older gang bosses. Seijun Suzuki argued that the Nikkatsu films were less political than Toei’s ninkyo eiga, which “even though they were yakuza films, they commented on social problems. But there was none of that in Nikkatsu films” (Schilling 2003: 98). However, the celebration of the modern and portraying those characters identified with the yakuza hierarchy as both old and uniformly devious and weak offers an at least implicit commentary on Japanese society.

A Colt is My Passport

This generational divide is a reflection of one of the major sources of the Nikkatsu Action style, the series of movies the studio released featuring rebellious youth, beginning with “Sun Tribe” films such as Crazed Fruit (1956, Ko Nakahira). The discontented teenagers of these movies who reject the weak or hypocritical ways of their elders are the precursors of the young lone wolf heroes of the action films, as both live “outside the usual Japanese matrix of family, community and workplace, with its myriad of obligations and rules” (Schilling 2007: 5). This fantasy of apartness from mainstream Japanese society was also present in another of the sources of Nikkatsu’s yakuza films, the mukokuseki (“no-nationality”) action genre which replaced the “Sun Tribe” films. Where the ninkyo eiga were set in a particular era and in specific urban places more or less realistically portrayed, the mukokuseki were “rooted in no particular place or time that link the setting specifically to Japan” (Vick 6). What they offered were youthful loner heroes operating outside, perhaps even rebelling against, the constraints of Japanese society while enjoying a lifestyle far more glamorous than that of most of their audience. As Mark

Schilling notes, these protagonists “pursued their enemies in speed boats or new-model cars (both then far beyond the reach of the average punter), not on bicycles or trains” (Schilling 2007: 7). They were fantasy figures, and a key part of this fantasy was their identification with the West, particularly the United States. The films borrowed “blatantly” from Hollywood and their stars (including the biggest, Yujiro Ishihara and Akira Kobayashi) “had the swagger, moves and even long legs of Hollywood movie heroes” (Schilling 2003: 30; Schilling 2007: 5). Nikkatsu’s yakuza films were essentially mukokuseki, featuring the same stars in the same settings sporting the same attitudes, except they were now gangsters. Toshio Masuda even described his Gangster VIP (1968) as a “youth film that happens to be set in the yakuza world” (Schilling 2007: 56). These movies cannot be described as realistic, but in one sense they were more faithful reflections of their era than Toei’s ninkyo eiga. As Schilling writes, the mix of Japan and Hollywood “was not just fantasy: it reflected the Western influences all around them” (Schilling 2007: 5). Toei used their pre-World War II settings to retreat from these influences, but Nikkatsu embraced them.

Hollywood was an important influence, but it was not the only one. Their films lifted elements from Westerns and film noir, but Nikkatsu filmmakers also borrowed from European directors. The frequent use of jump cuts and arbitrary plotting of Tokyo Drifter can be considered Godardian, while the protagonist of Velvet Hustler is loosely based on Jean-Paul Belmondo’s character in À bout de souffle (1960, Jean-Luc Godard) (Rist). Beyond the nouvelle vague, there is Velvet Hustler??’s “Antonioni-esque shooting style of long takes” (Rist) and ??A Colt Is My Passport??’s climactic confrontation in a desolate wasteland (in the middle of a city!), reminiscent of a Sergio Leone Western. The broad mix of influences even extends to musicals, as the Nikkatsu films often featured a catchy theme song for the hero to whistle as, for example, he tries to kill a gangster boss (??Velvet Hustler) or lies on the floor after being shot (Tokyo Drifter). In A Colt Is My Passport, the hero’s sidekick even takes a guitar that is conveniently hanging on the wall of their hotel room and sings the title song.

Tokyo Drifter

Despite Nikkatsu’s departures from the ninkyo eiga formula, there were similarities. The sympathetic gang bosses from the Toei films may have been missing, but the heroes often faced the same giri-ninjo conflicts. While they carried the air of film noir’s doomed heroes (what Schilling describes as a “dark, fatalistic funk” (Schilling 2003: 173)), they rarely actually were doomed. Instead, like the traditional yakuza with the katana sword, they generally were still standing after a carefully choreographed fight against overwhelming odds. Jo Shishido may take a few bullets in A Colt Is My Passport, but he kills all the bad gangster bosses and walks away, just like the hero in Gangster VIP. In Tokyo Drifter, the hero even gets to stroll away after apparently being shot dead! That the fights are carefully choreographed is important, as the other similarity between ninkyo eiga and Nikkatsu Action is a visual stylishness that can be identified with the Japanese cinema in general. It is there in the crisp black and white photography and stylized climax of A Colt Is My Passport, the brilliantly staged train station murder of a sympathetic yakuza in Gangster VIP, and in the pop art-influenced colour and sets of Tokyo Drifter. There are stylistic variations, of course. Toshio Masuda (Velvet Hustler, Gangster VIP) favoured long takes and a tracking camera, while there are not much more than a dozen moving camera shots in all of Tokyo Drifter, as Suzuki seems to have preferred establishing a striking composition for the characters to move around in. But not for too long, as there are also far fewer long takes. Regardless of individual preferences, the stylishness was central.

An exception to this is the climactic fight in Gangster VIP. While it does feature the hero being led away by the police after surviving a fight against a large gang, it is shot in a less stylized, more realistic style. As Schilling writes, it “is not the usual cathartic, precisely choreographed ballet . . . but a free-for-all brawl, with Tetsuya Watari fighting in a downpour with the desperation of a cornered rat” (Schilling 2003: 173). The staging of this “chaotic blood fest” has been described as a probable influence on Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles without Honour and Humanity series. (Rist) For Fukasaku’s five film series is a rejection of the visually stylish tradition, along with the glorification of the yakuza that were a hallmark of both the ninkyo eiga and Nikkatsu films. And while Nikkatsu offered rebelliousness as macho romanticism, the Battles series presented a comprehensive attack on Japan’s political establishment that went well beyond it. As the times changed and the ninkyo eiga became less popular as Japan entered a period of political strife marked by violent demonstrations, Toei turned to Kinji Fukasaku to provide a more realistic redefinition of the genre. Instead, he blew it up.

In the Battles films, Fukasaku was inspired primarily by international models. But where the Nikkatsu films had looked toward Hollywood genre cinema and the playfulness of the nouvelle vague, Fukasaku was strongly influenced by Italian neo-realism and the new cinema-vérité documentary style which had arrived in the early 1960s. (Mes) Where the ninkyo eiga offered nostalgic portraits of pre-war Tokyo and Nikkatsu a selective, glamourized version of modern Japan where even a desolate junkyard (such as the one in the climax of A Colt Is My Passport) could become beautiful and mysterious, Fukasaku showed provincial cities with ugly or nondescript buildings. As the Battles story progresses from the immediate post-war rebuilding through a period of increasing affluence, Fukasaku found visual metaphors to express his ideas, “replacing the ruins and slums [of the 1940s] with heaps of trash and refuse, the by-products of the economic miracle the government was so eager to promote” (Vick 43). Similarly, the series title signals the intention to remove any hint of romance from the yakuza. There are no giri-ninjo conflicts. This is a Darwinian world where the weak and the immoral thrive, while those who attempt to cling to some sort of yakuza code (not that there are many) die quick and bloody. Even Honzo (Bunta Sagawara), the nominal hero of the series, is much less successful than his amoral rivals, has to spend several stretches in prison and his occasional adherence to yakuza codes is mocked by the filmmaker, as in the farcical scene where he cuts off his finger. Usually an iconic act staged with great seriousness, in this film the finger goes flying and Honzo and his fellow gangsters have to hunt around for it, finally finding it being gnawed on by a chicken. And Honzo is hardly an idealized hero in the ninkyo eiga or Nikkatsu mould. He kills clumsily, administers several frenzied beatings to underlings and, interestingly, is often shown making decisions that have disastrous consequences for his friends, allies and subordinates. As Thomas Vick writes, these films “depict the yakuza as amoral, ruthless thugs – hardly the inheritors of the samurai code they believed themselves to be” (Vick 62).

These thuggish yakuza are different from their predecessors in another way. Seijun Suzuki said of his Nikkatsu heroes that “a hero has to look stylish. If he dresses like a bum, he’s not a hero anymore” (Schilling 2003: 102). Instead of sharply tailored suits, the Battles characters often go in for wide brimmed hats, cheap sunglasses and loud Hawaiian shirts. Instead of the coolly efficient professional epitomized by Jo Shishido in A Colt Is My Passport, these guys are klutzes. Their hands shake when they fire a gun, and they often miss what they are aiming at. They cry and squirm when things go wrong, and then loudly lie about how cool they were afterward. The funniest example of the level of gangster incompetence is from the final film, when one of Honzo’s men stalks a gangster chief with a harpoon gun, and then accidentally shoots himself in the foot. An additional difference is that instead of focusing the action on the star/hero, Fukasaku presents a wide canvas with the various gangsters becoming a collective protagonist. Bunta Sagawara is top billed, but there are long stretches (including most of the second film) where he disappears and other characters carry the story. The most important distinction is that, unlike their predecessors, the Battles yakuza rarely succeed in achieving their goals, and all but a couple of the central characters introduced at the beginning are killed before the end. Few walk away in the manner of a Nikkatsu Action hero. As Mes and Sharp argue, their defining characteristic is “they never got what they were after” (Mes and Sharp 44) and that the message of the films were directly opposite to the traditional one where an honourable loner achieves some form of victory. Instead, Fukasaku presented a world where poorly educated men fought with “brutal, almost spastic, violence, but against the combined powers of state, corporation and respectability, a single man is bound to lose” (Mes and Sharp 46).

This subversion of genre clichés also extends to the attitude toward the modern. The ninkyo eiga romanticizing of the traditional is deflated early in the first film when Honzo shoots a yakuza with a katana sword (eight years before Harrison Ford shot the swordsman in Raiders of the Lost Ark). On the other hand, there is no Nikkatsu-like celebration of the modern. The technology is constantly failing as guns jam or run out of bullets and cars stall or careen wildly. Modernity is not identified with an admirable character, but rather with sterile skyscrapers where the yakuza bosses attempt to turn themselves into modern businessmen. And a typical swipe at American culture (beyond the repeated presentation of the occupying U.S. soldiers as corrupt, racist and violent) is the scene where the upright civilian refuses to drink the contraband Coca-Cola brought home by his yakuza brother-in-law.

In order to capture the chaos of post-war Japan and the clumsy bursts of violence that really characterized the yakuza, Fukasaku departed sharply from the stylish visuals of the earlier yakuza films. Instead, inspired by documentary, neo-realism and new American directors such as William Friedkin and Martin Scorsese (Mes and Sharp 46), he filmed on the streets with hand-held cameras, using natural lighting, extensive use of the zoom lens and different types of film stock. He then intercut this with montages of photos, newspaper clippings, freeze frames at crucial moments (notably deaths of any of the main characters) and newsreel footage. Captions giving specific dates and places add to the documentary flavour. There is little or no attempt to compose shots. It seems more like Fukasaku was deliberately not composing for the frame, instead seeking an anarchic rawness in skewed angles and abrupt cuts.

While the ninkyo eiga and Nikkatsu Action films had some general (if largely implicit) social commentary, the Battles series was much more explicitly political. Bunta Sagawara states that the films “present a picture of Japan as it was at that time – although they deal with the yakuza, they’re not only about them. Even in straight society, people were cheating one another” (Schilling 2003: 138). Fukasaku was a teenager during World War II, and saw the defeat, symbolized by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima which is the opening image of each film, as a clean slate for Japan to start over, that “the destruction and chaos caused by the war would release a new energy in Japan, sweeping away the old values that had brought the nation down” (Vick 61). The Battles films are an allegory of what happened instead, a shout of outrage at the collusion between gangsters and politicians that created a corrupt society dominated by American culture whose “economic miracle” left many ordinary Japanese behind. The first film shows a gang war started by yakuza factions taking different sides in a by-election campaign. In later films, there are repeated parallels drawn between politicians and gangsters, while in Part 3: Proxy War, the critique is extended to Japan’s role as a pawn of American Cold War foreign policy, as political dominance is equated with cultural dominance. As Mes and Sharp write, Fukasaku “spits his venom, in outrage over being betrayed by the country that once expected him to sacrifice his life, but which has now moulded itself in the image of the former enemy” (Mes and Sharp 46).

In the 1960s and 70s, yakuza films reflected the times they were made, both in content and style. While ninkyo eiga updated a longstanding genre to express uneasiness with modernity by having symbols of it being defeated by traditionalist heroes, Nikkatsu Action films produced a semi-parody of the form to express uneasiness with the traditional and celebrate the modern and the international. In the Battles series, Fukasaku criticizes both anti-modernist nostalgia and modernity, particularly when it is in the form of Americanized culture. This critique is not only in the deglamourized content, but in the raw style that rejects the pictorial beauty that had arguably been a defining characteristic of Japanese cinema.

Fab Press’ Excellent Book on Nikkatsu noir

Works Cited

McDonald, Keiko. “The Yakuza Film: An Introduction.” Reframing Japanese Cinema: Authorship, Genre, History. Ed. Arthur Noletti Jr and David Dresser. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1992. 165-192.

Mes, Tom, and Jasper Sharp. The Midnight Eye Guide to New Japanese Film. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 2005.

Mes, Tom. “Kinji Fukasaku: Truth, Hope and Violence.” Midnight Eye: March 10, 2001.

Rist, Peter H. “‘Nikkatsu Action’ at Fantasia.” Offscreen 12.11: November 30, 2008.

Schilling, Mark. No Borders No Limits: Nikkatsu Action Cinema. Godalming, UK: Fab Press, 2007.

—-. The Yakuza Movie Book: A Guide to Japanese Gangster Films. Berkeley, CA: Stone Bridge Press, 2003.

Vick, Tom. Asian Cinema: A Field Guide. New York, NY: Collins, 2007.