Italy by Caliber 9—The Films of Fernando di Leo

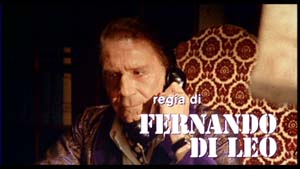

With 17 films as a director and about 50 scripts from 1964 to 1985, when the inexorable crisis of Italian cinema pushed him into a forced retirement, Fernando di Leo is one of Italy’s most interesting yet underestimated personalities of the period. Born in San Ferdinando di Puglia in 1932, the literate, open-minded, nonconforming di Leo always chose to do things his own way. To consider him as just the director of Milano calibro 9 (shot in 1971 but released in Italy in early 1972) would be a mistake. With his crime films based on the novels of Giorgio Scerbanenco, di Leo described the Milanese underworld with harsh, at times brutal realism, and with memorable results. Yet one cannot underestimate di Leo’s output outside the noir genre: with such films as Brucia ragazzo brucia (A Woman on Fire??/ ??Burn, Boy, Burn, 1969), Amarsi male (A Wrong Way To Love, 1969) and La seduzione (Seduction, 1973), the director portrayed female psychology and desire on screen with a sensibility that was quite different from Italian erotic cinema of the period. Even though he made “commercial” and genre films, di Leo was able to maintain autonomy, producing many of his works with his own production company Daunia 70, from 1969 to 1976; he also wrote almost all of his scripts. It’s not an exaggeration to consider him an auteur with a precise and coherent artistic trajectory inside Italian cinema of the 1970s. Take the dialogue, for instance: di Leo’s characters talk in a peculiar, literate manner, even when they are murdering, torturing or making love, while the use of dialectal terms both as a euphonic device and as an anthropological connotation achieves extremely complex effects. This is not to say di Leo made only good films: his oeuvre is extremely discontinuous, and opaque and routine works rub shoulders with overlooked gems. Yet even his failures and his minor efforts have interesting elements: the controversial, ambitious pro-Feminist parable Avere vent’anni (To Be Twenty, 1978) has a nasty sting in the tail, with an ending so abrupt, cruel and downbeat that it caused the film to be hastily reedited, and its powerful message not just softened but completely overturned.

After a brief stay at Roma’s Centro Sperimentale, di Leo made his debut as a director in 1963, with Un posto in paradiso, an episode of the omnibus comedy Gli eroi di ieri… oggi… e domani… co-directed with Enzo Dell’Aquila, which had censorship trouble due to its explicit anticlerical overtones. But his first real breakthrough was as a scriptwriter. Although his name does not appear in the credits, it is widely acknowledged that di Leo co-wrote Sergio Leone’s Per un pugno di dollari (For A Fistful of Dollars, 1964) and Per qualche dollaro in più (For A Few Dollars More, 1965). In those years he scripted a number of spaghetti westerns, all among the most original and interesting of the period, such as Florestano Vancini’s I lunghi giorni della vendetta (Days of Vengeance, 1967, very loosely based on Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo) and Giorgio Capitani’s Ognuno per sé (Every Man For Himself??/ ??The Ruthless Four, 1968, a sort of remake of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre with homosexual and Oedipal implications).

The western was the top-selling genre at the time, whereas no one really seemed to care about film noir, although Pietro Germi had directed several outstanding examples in the ‘40s and ‘50s (La città si difende??/??Four Ways Out, 1951; Un maledetto imbroglio??/ ??The Facts of Murder, 1959), Italian audiences preferred the exotic, hyperbolic, innocuous homemade James Bond rip-offs. One of the few exceptions was Carlo Lizzani’s Svegliati e uccidi??/ ??Wake Up and Die (1966), based on the true story of Luciano Lutring, a petty crook turned into a celebrity by Italian media, starring Robert Hoffmann and Gian Maria Volonté; Lizzani’s follow-up, the powerful Banditi a Milano (1968), based on another true story about a robbery gone wrong in the centre of Milan, paired its sociological ambitions with a style that was part action part cinéma-vérité. Even though Lizzani’s films did rather well at the box office, producers were skeptical about the idea of crime stories portraying a realistic Italian setting: Marco Vicario and Bino Cicogna flew to America to produce Giuliano Montaldo’s Gli intoccabili/Machine Gun McCain (1968), with John Cassavetes in the lead role.

Di Leo loved the noir/crime genre: he discovered Hammett through the French writer André Gide (“At first I was really intrigued by the fact that Gide cited him as an author on a par with Hemingway or Steinbeck”) and was an avid viewer of old Warner and RKO noir flicks. He decided to try and find his own way to Italian film noir –one that would be different from both the sociological approach of Lizzani’s films and the ‘American’ approach. His first effort was the script for Omicidio per appuntamento (Date For a Murder, 1967), based on Franco Enna’s novel Tempo di massacro 1 , written in 1955: di Leo updated the setting to contemporary Rome and contaminated the hard boiled plot (a womanizing private eye investigates his best friend’s disappearance) with nods to contemporary spy movies (the hero is Giorgio Ardisson, agent 3S3 in Sergio Sollima’s spy flicks), while keeping the tone consistently between seriousness and self-parody, with unexpected grotesque and nasty gags. The director, former journalist Mino Guerrini, adopted an exhilarating, colorful pop style, with unusual stylistic inventions and a remarkable use of handheld camera (by future director Camillo Bazzoni). The following year, di Leo and Guerrini helmed Gangster ’70, but this time there was no room for jokes: the main theme was the typical robbery-gone-wrong scenario, owing both to French classics such as Rififi and American ones such as The Asphalt Jungle and The Killing. If Omicidio per appuntamento had been lively and cartoonish, Gangster ’70 was mournful and desperate. The style was more controlled, too, even though far from flat: nervous cuts, hand-held camera, sequence shots perfectly amalgamated within the narrative, accompanied by an outstanding score by renowned experimental composer Egisto Macchi. It’s the story of an elderly gangster (Joseph Cotten) who is released from prison and organizes one last, extremely elaborate heist. His accomplices are an old friend (Giampiero Albertini) who earns his living as a cheat, a drug-addicted champion of clay-pigeon shooting (the great Giulio Brogi) and a failed actress (Franca Polesello) with suicidal tendencies: a bunch of failures who are looking not just for money, but for redemption, in order to prove to themselves they are still alive and have not been left behind by life in a fast-paced world. Di Leo and Guerrini focus on important themes: defeat, betrayal, dignity and self-respect. But they leave no room for hope, turning their nameless gangsters – who call themselves by nicknames: “Mezzo Miliardo,” “Sempresì,” “il Viaggiatore” –into Italian counterparts of the existential protagonists of Melville’s Le deuxiéme souffle or Le cercle rouge.

Gangster ’70, released at a time when the market was flooded with erotic thrillers, was a flop at the box office. Yet it’s a fundamental work, a forgotten gem that predates di Leo’s best work as a director, such as Milano calibro 9 and a flop Diamanti sporchi di sangue. Guerrini’s career would go downhill from here, while di Leo started directing his own scripts: a war flick (Rose rosse per il Führer??/Red Roses for the Führer, 1968) and a couple of erotic films: ??Brucia ragazzo brucia and Amarsi male. For his fourth film, I ragazzi del massacro (Naked Violence, 1969) he returned to noir territory, adapting a book by Giorgio Scerbanenco (1911-1969). Scerbanenco, Italy’s most talented crime novelist, paved the way for Italian crime writers to come with the cycle dedicated to former doctor-turned-inspector Duca Lamberti, started by 1966’s Venere Privata. 2

Yet di Leo does not follow the book to the letter: Lamberti (Pier Paolo Capponi) becomes a tough cop who somehow predates the heroes of the 1970s poliziotteschi, but prefers verbal aggressiveness to brute force, while the plot is reduced to a bare skeleton. I ragazzi del massacro is almost a kammerspiel: the first half, tense, minimalist, almost abstract, is entirely set within the four walls of Lamberti’s office, where the protagonist interrogates eleven teenagers who raped and slaughtered their evening school teacher. Other interiors are mostly bare, just as if in a theatrical play, while Silvano Spadaccino’s score accompanies the characters’ entrances and exits. The “boys of the massacre” themselves are quite unlike Pasolini’s non-actors taken from the street, but also very different from the clean-cut “juke-box rebels” that could be found in Italian popular cinema in those days. Unrealistic and patently ugly-looking, visibly older than their role, carrying grotesque wigs and shot through deforming wide-angle lenses, “…they almost seem to carry their ugliness like a mark, the sign of an ancestral sin: they are the living abortions of a society gone mad.” 3 The most memorable moment in an admittedly discontinuous film is the opening gang rape, shown through obsessive and unsettling wide-angle, handheld camera shots: the bodies and hands of the assailants surround, graze, undress the victim, yet no direct physical contact is shown at any time. It’s an excruciating experience for the viewer, and a directorial tour-de-force that perfectly captures the “disordered, irrational hysteria” described in Scerbanenco’s pages.

Coming after a minor giallo (La bestia uccide a sangue freddo/Slaughter Hotel, 1971) which nevertheless gained much more visibility than his better works, Milano calibro 9/Milan Caliber 9 (1972) is the heart of di Leo’s cinema, a movie where everything fits in magically, as if the director worked in a state of grace: actors, dialogue, pacing, the marvelous score by Luis Enriquez Bacalov. The story of Ugo Piazza (Gastone Moschin), a small-time crook who is released from jail after a three-year sentence, only to find that old acolytes waiting for him because they suspect he stole 300,000 dollars from them, shows the director’s love of classic American and French noir: John Huston, Nicholas Ray, and Jean-Pierre Melville. First of all, there is the sense of an imminent, inescapable, mocking Fate: a feeling which was originally emphasized by the inclusion of dates and timelines superimposed on screen, like a countdown (the working title was Da lunedì a lunedì??/ ??From Monday To Monday). But even more impressing is how di Leo adapts on screen one of Giorgio Scerbanenco’s short stories, distillng the writer’s universe and making it his own. “When I read his books, I realized that we shared the same vision of the world. He was a realist, he wrote about petty crooks and small-time criminals.” Much more so than di Leo’s previous Scerbanenco adaptation, I ragazzi del massacro, Milano calibro 9 preserves the spirit rather than the letter of Scerbanenco’s pages: the central sequence set in the heart of Milan, piazza Duomo, which follows two couriers exchanging mysterious packets and ending with two simultaneous, unexpected bomb blasts, comes from the short story Stazione Centrale ammazzare subito, from the omnibus Milano by Calibre 9: the rest is all di Leo’s.

Milan, the so called “black Milan” described in Scerbanenco’s books, has never been so impressive: foggy canals, decaying popular houses, sleazy nightclubs, empty parking lots. Di Leo doesn’t go for sociological notations, but films Italy’s biggest Northern city with a realism unknown to genre cinema. The stark contrast between ultramodern, stylish apartments and squalid hotel rooms echoes the hiatus between the luxurious headquarters of the big boss, the ‘Americano’ (Lionel Stander) and the poor, minuscule apartment where the old and blind mafia godfather (Ivo Garrani) lives with his sidekick, Chino (Philippe Leroy). Di Leo synthesizes the escalation of a new form of criminality replacing the old one. “They call it the Mafia, but they’re just gangs. Gangs fighting each other. The real Mafia does not exist anymore. When drug dealers want to invest their earnings, they build apartment blocks. So the construction gangs kill them. Where’s the Mafia in that? The real mafia is gone.”

The difference between old and new criminality is a matter of methods and mentality: something which has been understood very well by the ‘Americano,’ whose motto is “Do unto others what they what they would do to you… before they do it!” –an aberration to those who still follow old concepts such as honor, respect, ‘rules’ (at one point Chino says: “I’ll do whatever you want, but don’t ask me to break the rules.”) which actually no one follows anymore. On the other hand, there are many loose dogs raising their heads, claiming their share with violence or craftiness: violence generates only violence, in a chain reaction that will end with no winners.

Scerbanenco’s characters are taciturn, and Ugo Piazza is no exception. He’s a monolith of a man: cold, with undecipherable icy eyes. It was a brave move to choose for this role an actor such as Gastone Moschin, often seen in comedies (such as Pietro Germi’s wonderful Signore e signori, 1966) playing simpletons or awkward types. Di Leo reinvents Moschin, turning him into a sort of Milanese version of Lino Ventura in Melville’s films: his hands in the pockets of his Marine jacket, his eyes fixed on the ground to avoid other people’s stare, walking fast along the canals of Milan. Mario Adorf, who plays the obtuse, bovine Rocco Musco, the Americano’s right hand, is precisely the opposite: vulgarly elegant, with greasy hair and an Errol Flynn moustache, he is a subtly caricatured presence (just as the other gangsters, whose features and movements are deformed with twitches and scares) yet a vital one in the film’s economy. It’s Rocco whom Piazza meets first, when he gets out of jail, and the very first scene between Adorf and Moschin in Rocco’s car is a small masterpiece in its own, with Rocco alternating enticements and allusive treats while Ugo stays silent.

Friends, Nicò, Pasquà, this is Ugo, Ugo Piazza, he used to work with us and he liked it. You guys like it too, right? Didn’t you like it, Ugo? You liked it, you liked it! He liked it! But he wanted more… Right, Ugo?

Di Leo plays on the contrast between the imperturbable Moschin and Adorf’s hammy overacting. Rocco loves to make a scene in front of his men, showing off his power: on the contrary, Ugo just keeps a low profile, waiting for his chance. A chance that comes when the gang war between Chino and the Americano ends with no survivors. Di Leo shows Ugo’s steps –first hesitating, then running in an irresistible euphoria– in the beginning of a long, speechless sequence which follows Piazza to the abandoned house in the country where he has hidden the 300,000 dollars that he had stolen, after all. Ugo looks like a winner: after the jail, the beatings, the fear of being killed that accompanied each and every move he made, he can finally think about the future. Too bad he has not got one.

As the mythology of noir demands, the man is always in love with the wrong woman. Milano calibro 9??’s femme fatale has the angelic features of Nelly (Barbara Bouchet), Ugo’s lover: unbeknownst to him, she has paired up with a younger man, Luca, whom Ugo treated like a boy (“Have you seen how much he’s grown up?” somebody tells Ugo at one point). And together they set a trap on Ugo to get the money. The bitter irony of ??Milano calibro 9 is in the string of coincidences, all of them conspiring for an ending which was written into the characters’ DNA. As events unfold, the game of appearances which the film –and life itself– is built upon, just collapses. Smartness becomes foolishness, love turns into treason, hostility is replaced by respect. That’s why the film ends with an unexpected deus ex machina: Rocco, whose hatred towards Piazza has turned into admiration, becomes Ugo’s avenger, killing Luca with his own bare hands while shouting:

You can’t backstab a man like Ugo Piazza! You’d better not even touch someone like Ugo Piazza! Don’t even go near someone like Ugo Piazza! When you see someone like Ugo Piazza, you’d better tip your hat!”

Everything’s lost. Ugo’s been killed like a dog: the only thing that’s left of him is honor. A key value of a long-lost code, which is desperately reaffirmed by someone who has just realized that it’s gone forever. The very last shot is that of a cigarette slowly consuming away, on the edge of a table: a brilliant image which synthesizes a vision of the world, life, and cinema.

In La mala ordina (Manhunt, 1972) the Melville references leave way to a cruder, caustic look. Once again, the inspiration comes from Scerbanenco: even though it’s not mentioned in the opening credits, the basic plot (two American killers are sent to Italy to kill a Milanese pimp who is suspected to have stolen Mafia money) is taken from the short story Milan by Calibro 9 (“They smiled gently to everyone, with their enormous alligator teeth,” so Scerbanenco describes the two hit men). But obviously di Leo had in mind Hemingway’s The Killers and its two screen renditions for the sense of fatality which permeates the man hunt. But in La mala ordina the prey, unlike in Hemingway’s tale, doesn’t wait for his death. Di Leo wanted to call the film Ordini da un altro mondo (Orders from Another World), thus suggesting the idea of a transversal, a class view of the underworld, where the ‘other world’ is that of the American Mafia, which subjugates and dominates the Italian one. But for small-time crooks like Luca Canali (Mario Adorf), the ‘other world’ is represented by the Italian godfather, don Vito Tressoldi (Adolfo Celi), who rules the city from his headquarters in the center of Milan. Not as tightly constructed as Milano calibro 9, La mala ordina nonetheless is a savage crime film, filled with adrenaline and violence: the first part follows the two killers (Henry Silva and Woody Strode) in search of their target, the second opens with a show-stopping action sequence in which Canali chases the hit-and-run killer who murdered his wife (Sylva Koscina) and daughter, first by car, then by foot in a deserted amusement park. The ending, which takes place in a car scrap yard and sees Canali confronting the two killers, has a timing and mise-en-scene worthy of Sergio Leone, and has been read by some critics as an ironic take on the aftermath of Italy’s ‘economic boom’ of the Sixties.

La mala ordina is also a sensual film, especially when Femi Benussi is on screen: moreover, it’s also a sum of Di Leo’s universe, a catalogue of characters, places and actors who will return in later films, such as Woody Strode (to be seen again in the sexy crime spoof Colpo in canna, 1974) and Henry Silva. But ??La mala ordina??’s main asset is Mario Adorf. His character looks like a clone of ??Milano calibro 9??’s Rocco Musco, and seems like a parody at first: then it turns into a sort of metropolitan Cuchillo (the character played by Tomas Milian in Sergio Sollima’s La resa dei conti/The Big Gundown) who gains a tragic dimension and a dignity that others denied him.

After the two films dedicated to the Milanese crime world, Il boss (1973) is a mafia movie set in Sicily, loosely based on a novel by Peter McCurtin. Di Leo’s Palermo is different from the way the city is usually portrayed –a nocturnal, indefinite, depopulated town– while the vision of the “men of honor” is corrosive and demystifying. The web of pacts and alliances upon which mafia families base their power is first postulated, then systematically contradicted by the continuous double and triple-crossings: everyone betrays everyone, and there’s no room for dignity and honor. Di Leo follows the steps of Lanzetta (Henry Silva), a cold-blooded hetman and the right arm of mafia boss Don Carrasco (Richard Conte), with ferocious sarcasm, if one thinks that the boss’ motto is “You can count on my word.” There is no real ending, and no real catharsis: just a series of murders. The ‘Mafia’ is a monotonous affair: killing and being killed. And the movie ends with the sign “continua” (to be continued…). The violence is conspicuous and over the top: in the beginning Lanzetta breaks into a projection room where a bunch of mafia men are watching a porn movie, and slaughters them with a grenade launcher. But it’s language that connotes the ruthlessness and the squalor of the mafia world: death orders come in vague, allusive formulas (corpses become “complications” or “difficulties”), where what is left unsaid has more importance than the words that are spent, in a sort of secret code known only to the affiliates –themselves, a bunch of illiterate, childish brutes. Free from the rules of ‘committed’ cinema, di Leo doesn’t spare institutions as well: anti-mafia members who pretend not to see the Mafia war that’s going on, a police commissioner (Gianni Garko) who’s bribed by the godfather and who thinks and speaks just like a picciotto, his disillusioned superior (Vittorio Caprioli) who gives vent to his impotent rage with sarcasm (“We are all Vietnamized!”). What’s more, the ties that bind Mafia bosses and politicians, with the formers controlling and channeling votes, are not simply hinted at, and the cardinal who receives Richard Conte is a patent reference to the then archbishop of Palermo, Ruffini, who in an infamous speech had stated, “the Mafia does not exist.” And this at a time where Democrazia Cristiana (the Christian Democrats), the party di Leo clearly associates with the Mob, was Italy’s prominent political force.

Di Leo’s anarchic temper is equally evident in Il poliziotto è marcio??/ ??Shoot First, Die Later (1974), where inspector Malacarne (Luc Merenda) proudly announces: “Yes sir, I’m corrupt! I’m a scoundrel and a traitor! I got 60 million in my bank account, a high-class lover, and whenever I raise my voice everybody stands up at attention!” In the parade of honest, incorruptible, heroic commissioners that populated Italian poliziotteschi, Malacarne is the only real negative antihero, a black sheep in a world of idealists that see their job as a mission. Malacarne doesn’t care what’s wrong or right: he just worries about the monthly payment he receives from cigarette smugglers. It’s the one and only case in the whole genre, once again a proof of di Leo’s subversive approach to clichés. In 1974, a year in which Italy underwent massacres, kidnappings, terrorist actions, the so called poliziotteschi were already a well-established moneymaking business, after the success of such films as Stefano Vanzina’s La polizia ringrazia??/ ??Execution Squad (1972) and Enzo G. Castellari’s La polizia incrimina, la legge assolve??/ ??High Crime (1973), di Leo’s film is a slap in the face, a punch below the waist, starting with the title itself: literally, The Cop is Rotten.

That title was a real insult for many. People used to rip locandinas [one-sheet movie posters] into pieces. I even received anonymous phone calls: ‘You have to stop with this crap!’ […] For a country like Italy, born from the hasty fusion of two large blocks of regions, both bureaucratic and authoritarian, the Reign of Piedmont and that of the Two Sicilies –both States with repressive police forces– plus twenty years of Fascist regime, the very title was an act of provocation. 4

Despite the apparent plot affinities, Il poliziotto è marcio is not just an atypical oddity: rather, it’s a thought-provoking and critical antithesis of the crime film genre. Di Leo apparently follows the rules, just to get rid of them when one least expects it: the opening half hour gives the viewer a hero to identify with, in a spectacular crescendo that culminates in a car chase that’s among the most exhilarating action sequences ever seen in an Italian film. Then it shows the hero to be a corrupt son of a bitch who covers the deeds of a scummy crime boss: the mechanism of identification has gone to pieces. What’s more, the ‘rotten cop’ Malacarne (a name which translates literally into ‘bad breed’), the Robin Hood au contraire who steals from the poor and gives to the rich, has the Apollonius features of Luc Merenda, the incorruptible cop of so many crime flicks. In di Leo’s universe there’s no room for the dialectic between sin and redemption: and the inevitable bad ending is not cathartic at all. Nor is violence, for that matter: always unexpected, cruel, disturbing. Even though it’s basically a work for hire, the first he did for producer Galliano Juso, and despite a flawed script, Il poliziotto è marcio features among di Leo’s best and ideally closes a cycle, not only for its author, but for the crime film as well.

Colpo in canna??/ ??Loaded Guns (1974) is the result of the awareness that “farce is the funnel where, sooner or later, all genres flow together.” 5 A “divertissement in two acts,” as the credits announce, Colpo in canna is an unexpected change of register, starting from the sunny, warm Neapolitan setting. Instead of choosing a broad parodic approach, di Leo injects an otherwise straight-faced crime plot (a hostess is involved in a war between rival gangs) with extraneous elements. In the place of the usual tough cop, we have comedian Lino Banfi, for instance. But the most interesting move is the use a female lead (Ursula Andress) who behaves just like a man. Colpo in canna is a ‘gynocentric’ movie, dominated by Andress’ gorgeous body: she beats and is beaten, kicks and run, cheats and deceives, and goes to bed with whoever she wants. Originally the script described her as bisexual, but di Leo abandoned the idea as it was too ‘strong’ for Italian audiences; yet it confirms the director’s attention to unconventional female figures. But hostess Dora Green, who uses her own body as a weapon, predates the two protagonists of Avere vent’anni. Di Leo has fun turning the usual noir macho attitude upside down: men are brainless studs or retarded buffoons, and all of them lose their mind at the sight of a nice pair of legs. And it serves them right.

La città sconvolta: caccia spietata ai rapitori/The Kidnap Syndicate (1975) is another work for hire, but the results are far inferior to Il poliziotto è marcio. The plot, co-scripted by di Leo and producer Galliano Juso, centers on kidnappings, a then sadly frequent phenomenon in Italy, introducing a class overtone: a gang kidnaps the son of rich engineer, played by James Mason, together with another child, the son of a down-on-his-luck, proletarian mechanic (Luc Merenda). The contrast between the rich father –who does not want to pay the ransom– and the poor one, who would give everything he owns to get his son back, turns Mason into the real villain of the film. But even though the dialogue is generally above average, the result is shaky and far too conventional, considering di Leo’s usual iconoclastic approach. The first half owes too much to Akira Kurosawa’s High and Low, while the second is almost a remake of La mala ordina, without the power and inspiration of the model. Not much better would be the director’s following film, Gli amici di Nick Hezard/Nick the Sting (1976), another work for hire: di Leo had to use a preexistent script (by Alberto Silvestri), which to describe as a rip-off of George Roy Hill’s The Sting would be an understatement. Yet, accordingly, it was quite a good script, with just a few problems: a) to film it exactly as it had been written would have cost a fortune; b) it desperately needed a charismatic lead. And di Leo didn’t have Robert Redford, nor Paul Newman, but Luc Merenda, who was rather good at playing tough cops, but hardly believable as a master con-artist. The shooting became a nightmare: “We were going way over budget. Merenda was not convincing and the other actors looked stilted as well. It was all getting too forced and banal. That beautiful script was falling to pieces. I knew I was not going to make a good movie, and that really made me sad, but there was nothing I could do. What’s more, we just didn’t have enough money.” 6 The only solution was to cut costs, i.e. all the most expensive and complex scenes, and to reduce Merenda’s role whilst giving more room to other cast members. “It was a most strange situation. I had to mutilate a good film, substituting the best scenes with other less than good stuff. It was absurd – just as if you refuse caviar and go for sardines hoping that you’ll have a better meal!” The result, though, was more like bread and water.

After a couple of interesting scripts –Romolo Guerrieri’s Liberi armati e pericolosi, once again based on Scerbanenco, and Ruggero Deodato’s hyperviolent, subtly parodic buddy cop movie Uomini si nasce poliziotti si muore, both released in 1976 –his next film as a director would see di Leo return to more favorable territory. I padroni della città (Mr. Scarface/Rulers of the City, 1976), starring Jack Palance as “Mr. Scarface,” is the umpteenth incursion into the underworld. But unlike Milano calibro 9 and La mala ordina, there is a ironic, picaresque vein that puts the film closer to such escapist fare as Colpo in canna. The title, for instance, promises an epic tone which is patently absent, since the main characters are all small time crooks, suburban gangsters who barely manage to make ends meet and gravitate to seedy bars and pool halls. No Godfathers or international Mafia wars here; instead, we have a wimp boss (Edmund Purdom) who is afraid of his own shadow; his right-hand man (Enzo Pulcrano) –an opportunist who can barely write his own name; a bully (Harry Baer) who drives a dune buggy and dreams of expatriation to Brazil. These are the “rulers of the city”: a small world soon to disappear, partly because of the new, violent organized gangs, and partly because of self-consumption. Yet di Leo’s approach is more indulgent and benevolent, especially in the scenes with Vittorio Caprioli as the elderly pickpocket who perhaps represents the director’s alter ego. I padroni della città was released a year after the death of Pier Paolo Pasolini, and di Leo paid homage to the director of Accattone by describing the Roman proletarian microcosm with warmth and sympathy. Despite a couple of not too convincing leads –Al Cliver is monolitical as usual, while Harry Baer, a Fassbinder regular chosen for co-production reasons, is hardly believable as a Roman– and a minuscule budget, I padroni della città is almost on a par with di Leo’s best, with several unforgettable sequences: the opening scene, with Palance killing Al Cliver’s father, shot in slow motion and a out of focus effect to evoke a barbaric past which has left an indelible memory; the exciting pursuit of Harry Baer in the streets of Rome (a moment that Quentin Tarantino, a great fan of this film, kept in mind while shooting the Steve Buscemi flashbacks in Reservoir Dogs); and the final showdown in the abandoned abattoir. As always with di Leo, dialogue is funny and pointed, sometimes sinisterly prophetic. Such lines as “You young people are always in a hurry: hurry to make money, hurry to steal, hurry to die!” almost scream for a metaphorical reading. The world depicted in I padroni della città reflects, perhaps involuntarily yet precisely, the state of Italian cinema at that time: unsteady and gasping for air, given the mass offensive of the first private TV stations (such as those owned by future movie mogul and mediatic dictator Silvio Berlusconi) and the continuous loss of audience.

I padroni della città was the last film produced by di Leo’s own independent company Daunia 70 Cinematografica. From then on, the director had to face increasing ecomomic problems with each subsequent film: shoestring budgets and difficulties in distributing the final products in a market which was getting more and more asphyxiated, even near invisibility. That was the fate of Diamanti sporchi di sangue??/ ??Blood and Diamonds, which opened in Rome on March 17th, 1978, the day after the Brigate Rosse (the Red Brigade) kidnapped the leader of Democrazia Cristiana, Aldo Moro, in an unreal setting: the city at night was deserted, movie theaters included. Diamanti sporchi di sangue bears many affinities, both thematical and plot-wise, to Milano calibro 9 (the script was originally called Roma calibro 9). It opens where the first film, Milano calibro 9, ended: an ashtray, a last cigarette smoked by cat burglar Guido Mauri (Claudio Cassinelli), while waiting for his boss Rizzo (Martim Balsam) to call him for a theft to be executed that night. But someone calls the cops. Guido’s accomplice, Marco (Roberto Reale) manages to escape, but Guido is arrested and spends five years in jail. When he is released, he has one thing in mind: revenge. But is Rizzo really the one who sold him to the cops? The analogies between the two films involve characters and their relationships as well: Cassinelli basically reprises the role of Gastone Moschin in Milano calibro 9, while Pier Paolo Capponi substitutes for Mario Adorf as the heavy; and there’s Barbara Bouchet too, dancing in a night club wearing a silver bikini as she did in the 1971 film. But Diamanti sporchi di sangue is less a remake than a reversal of Milano calibro 9, almost a dialectical counterpart of the first film. Unlike Gastone Moschin/Ugo Piazza, Cassinelli/Mauri does everything wrong: he’s so obsessed with vengeance that he starts a private war against his own boss, but he’s too blind to see the truth in front of his eyes. And he ends up hurting the people he loves. Violence is compressed and condensed in the character of Tony (Pier Paolo Capponi), a ‘mad dog’ with sadistic tendencies, impulsive and obtuse, unsettling and menacing with his theatrical gestures and discourse. But what strikes most is a sense of void and loss: Cassinelli is a sort of robot who walks through the film emotionless, as if already long dead inside. (Fernando di Leo: “He was surely not the world’s most expressive actor, but that was just what I needed, as such was the character he had to play.”) He mechanically abides by the rusted codes of the underworld: once he realizes it wasn’t Rizzo who betrayed him, he spontaneously surrenders to his boss, not to ask for forgiveness, but, as the ‘rules’ state, to be killed. Rizzo prepares an archetypal mise en scene inside an abattoir, where Guido has to walk between two lines of men like a lamb soon to be slaughtered. But Rizzo doesn’t kill Guido: he just shoots a bullet through his shoulder. Guido gets up, bewildered and clueless: there is no catharsis this time. If in Milano calibro 9 Ugo Piazza’s honor was celebrated by Mario Adorf’s homicidal fury, and survives in the memory of those who knew him, in Diamanti the fact that Guido is spared doesn’t change anything. Everything’s lost: pride and honor included.

Diamanti sporchi di sangue was di Leo’s last truly successful film. His following efforts were flawed, sporadically graced with brilliant ideas, such as the aforementioned ending of Avere vent’anni, or more than a few sequences of the underrated Vacanze per un massacro??/ ??Madness (1979), a sort or erotic kammerspiel starring Joe Dallesandro as an escaped convict who becomes the uninvited observer of a seedy love triangle in a desolate country house. But di Leo could not be blamed for the films’ many shortcomings. He was just trying to survive, like many others. The sudden disappearance of crime films in early 1980s was the consequence of the slow, painful death of the Italian film industry as a whole. Between 1980 and 1985 the number of spectators per year fell from 241,8 to 123,1 million: a defeat which was accompanied by many movie theaters being shut down or turned into adult-only venues. The collapse of the system involved the most representative auteurs as well as many directors who specialized in genre flicks, such as Stelvio Massi and Enzo G. Castellari, who survived by churning out low-budget made-for-video flicks designed for foreign markets –mostly Southern American ones. After an unfortunate experience with the TV series L’assassino ha le ore contate –six one-hour TV movies produced by Rai Uno and scripted by Fabio Pittorru, which are still unreleased to this day– and a shaky war action flick, Razza violenta??/ ??The Violent Breed, in 1984 he directed what was going to be his last film, Killer vs. Killers??/ ??Death Commando. Originally conceived as a remake of Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle, the final result was far from brilliant, yet at times even moving in its refusal to follow the path of contemporary action/crime films. Henry Silva once again plays the leading role, a taciturn hetman who is part of a commando sent to steal a formula in a military base. But the heist –which is hastily performed halfway through the film– is less important than what happens next: the dealer (Edmund Purdom) orders the members of the gang to be rubbed out. What is left of the Huston connection are the names of several characters (Jaffe, Sterling), while the director’s typically sardonic humour pops up here and there: a guy who’s carrying a bag chained to his wrist has his hand amputated with huge garden scissors; one of Silva’s associates always has a couple of girls dancing naked in front of him in his apartment (after the hit, the girls are four); Silva practices by shooting passers-by in a park with sedative bullets. But the budget is way too scarce, and it shows, especially in the action scenes. Overall, it looks as if di Leo got tired after a while: the final showdown in a zoo, with Silva killing enemies by the dozen with a bazooka, among escaped fiery animals, is exciting on paper but haphazardly shot. What’s more, co-producer Albert [Cola]Janni –who would gain some notoriety years later with his impression of politician Massimo D’Alema in satirical TV shows– is an absymal co-protagonist. Silva often tells him “You are not a professional!”: it sounds like di Leo’s private revenge against such a waste. Killer vs. Killers rapidly disappeared into oblivion: it wasn’t even released in Italy, where it surfaced over 20 years later on DVD.

Starting from the mid-nineties, cult magazine Nocturno Cinema introduced the work of Fernando di Leo to a new generation of fans, first with a massive, groundbreaking interview, then a number of features on his films and a whole monographic issue in September 2003, just a few months before the director’s death in December 2003. The 2004 Venice retrospective on the “Secret history of Italian cinema” marked the definitive critical recognition of Fernando di Leo as one of the most important Italian directors of the 1970s, and a true innovator of the crime and noir genre.

Notes

- Literally, Massacre Time, just like the Fulci western that di Leo had scripted one year earlier (Le colt cantarono le morte e fu…tempo di massacro). ↩

- Venere Privata was filmed in 1970 by Yves Boisset, with Bruno Cremer as Duca Lamberti: the result, Cran d’arret (in Italy Il caso Venere Privata) was a decent crime flick that nonetheless bears scarce resemblance to Scerbanenco’s vision. Duccio Tessari’s La morte risale a ieri sera (1970, based on I milanesi ammazzano il sabato) was much better, with good performances by Frank Wolff as Lamberti and Raf Vallone as a desperate father whose retarded daughter has been kidnapped by a white slavery racket. Of the four novels starring Lamberti, Traditori di tutti (which won the Gran Prix de la littérature policière in 1968) is still unfilmed to this date. ↩

- Andrea Bruni, I ragazzi del massacro, in Nocturno dossier n. 14, “Calibro 9. Il cinema di Fernando di Leo.” September 2003, p. 25. ↩

- Davide Pulici, Manlio Gomarasca, “Il Boss. Intervista a Fernando di Leo.” Nocturno cinema n. 3. June 1997, p. 26. ↩

- Davide Pulici, “Terzo movimento: il tempo del gioco.” In Nocturno dossier 14, “Calibro 9. Il cinema di Fernando di Leo.” September 2003, p. 36. ↩

- Davide Pulici, “Terzo movimento: il tempo del gioco.”In Nocturno dossier 14, “Calibro 9. Il cinema di Fernando di Leo.” September 2003, p. 33. ↩