In Real Time: An Interview with Jafar Panahi

On August 30th, Offscreen were able to interview the head of the official jury of the Festival des films du monde/World Film Festival (WFF), 33rd edition, in Montreal. Jafar Panahi is a great filmmaker, but, we think that he is also a very brave filmmaker, standing up for oppressed people in his films as well as in the public sphere. Some of us were surprised that he actually arrived in Montreal to fulfil his role as WFF jury head, as he had been arrested during the aftermath of “green” demonstrations against the alleged fixing of the presidential elections by the Iranian government. Few of Panahi’s feature films are ever shown publicly in Iran, but all of them have been distributed widely outside of his native country.

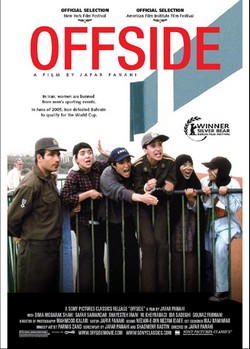

We discussed four of the five feature-length, theatrical films that Panahi had directed: Badkonake sefid (The White Balloon), which won the Camera d’Or (Best First Film prize) at Cannes in 1995; Ayneh (The Mirror), which won the Golden Leopard (Best Film prize) at Locarno in 1997; Davereh (The Circle) which won the Golden Lion (Best Film prize) at Venice and the annual FIPRESCI (International film critics circle) Film of the Year in 2000; Offside, which won the Silver Bear (Jury Grand Prize, or 2nd prize) at Berlin in 2006. The only one we didn’t discuss is Talaye sorkh (Crimson Gold), which won Panahi the Jury Award of the Un Certain Regard section at Cannes in 2003. We also talked about his short, “Untying the Knot,” one of the 15 parts of the 2007 anthology feature-length film, Farsh-e Irani (Persian Carpet).

Offscreen: I saw The White Balloon when it showed here in Montreal. I loved that film, but, I realized that Kiarostami wrote the screenplay. You had worked with Kiarostami before this film, and, it seems to me that there are similarities and differences in that film between Kiarostami and yourself, including the fact that you are working with a central female character. In most of your films you focus on a girls or women. And, I’m interested as well in the concept of “real time” although we can come back to that. So, if you could talk a little bit about your work with Kiarostami.

JP: As a student I made films and was an assistant for my professor’s work, and I then directed films for television. After this I worked as an assistant to Abbas Kiarostami on Through the Olive Trees. After this work was finished, and was quite successful, I started to work on my own projects. I asked Kiarostami to look at my initial treatment for The White Balloon and comment on it. I had anticipated that it would be a short film, but, he suggested that it could be a feature-length film. It is always difficult to start with a first project. While working in television I had met Kiarostami, and he later told the producers at the Centre for children’s filmmaking that I have a “great capacity” and that I would finish my work “perfectly.” He also agreed to write the full story/script for me. That’s how I was able to move from making shorter films to the feature-length format.

Offscreen: Yes, it is interesting to me that Kiarostami always worked with boys or men on his films, whereas you mostly work with girls or women, which is an interesting difference. I wonder if you could talk about your choice with working with a girl in your first two films. I think it is the same girl, Aida Mohammad Khani, in The Mirror?

JP: I lived in a working-class family and I had four sisters, and two brothers. I don’t know really where this comes from, but, when I started to work on The White Balloon, I was thinking that there was perhaps more involved in the central character’s make up than would be possible from a little boy’s perspective, and, the character in the second film was even more complex. And she was played by Aida’s sister, Mina, actually.

Offscreen: Anyway, they are both fantastic. I wonder what happened to them. Are they still acting?

JP: Unfortunately, no. With child actors we have a different way of working with them. And, if they don’t act correctly, things won’t come out as they should. Also, they get used to working with a particular director, and, if the child is then assigned to work with a different, or new director, she might not understand clearly what is expected of her. In fact, after The White Balloon Aida was slated to work with another director, whom I know, and who came to me after the first day of shooting and told me he had a problem with her. On my film, the sound recording was direct, but on this other film, she was told that they would add the sound later and she didn’t like that. She said that “when I play it must be my own voice,” and she was told that Mr Panahi works differently from us, and we will add the voice later. She stopped and told them not to say anything about Mr. Panahi, because (and, this is an Iranian expression) a “single hair from Mr. Panahi’s head is worth more than all of you.” Her act was clearly un-professional, and, she couldn’t give them the performance shading that they wanted. When they want to go on to the next movie, it is not easy for children to adapt.

Offscreen: Aida’s character in The White Balloon is very strong, which fits in with the female characters in your other films, and, her sister in The Mirror had quite a difficult challenge, because, in a sense, she was playing two roles. She is playing a character in the fictional story, and then, suddenly, the film shifts to a “documentary” mode because, defiantly, she decides that she is not going to play this role any more. In your first two films, were you trying to say something about girls, or women having an inner strength, which helps them overcome problems in their lives?

JP: I am confident that I can get actors to play what I want. So, the first challenge for me is to get to know the person who is playing for me. I selected her sister. Why? I detected a feeling of emptiness within her, and a determination to prove herself to the world. So I changed the negative aspect of her personality into a positive point. The important thing is for the director to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the player, and to build the character on this. At the children’s filmmaking unit [The Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, aka ‘Kanoon’] they had a very routine manner of working with child actors. I was different. I acted out the children’s roles in advance, to show what was expected of them. But, whereas he or she was copying me, there was always space for he or she to put him- or herself inside the role. In this way, things emerge perfectly well both from an image point of view and a film point of view.

Offscreen: In fact, this is probably the finest acting by young people I’ve seen since Vittorio de Sica’s Bicycle Thieves.

JP: In fact, my third film, The Circle is taken somehow from de Sica’s Bicycle Thieves. I was 15 or 16 years-old when I watched that film. It was something very interesting for me. Especially, the point at which the man, who has had his bicycle stolen, feels forced into stealing one himself.

Offscreen: Invariably, when the Italian title, Ladri di biciclette is translated into English, the plural, “ladri” becomes singular “thief,” and so, I insist on the title “Bicycle Thieves.”

I would like to ask a question on film style, now, but, before doing that I wanted to let you know that I teach a course, entitled “Moving Camera Aesthetic” and the last film we show on that course—we rent the film on 35mm from the distributor—is The Circle, because I think it provides a perfect connection between style and content, and with politics. I think it is a really great film, and, I wonder if you are familiar with the films of Max Ophuls, for example, La Ronde and The Earings of Madame de…, which are about relationships, where everything comes back to the beginning (like a circle), although this work is not “political.”

JP: No, I don’t think so.

Offscreen: So I am struck by how important the title of the film is, The Circle, in terms of the whole structure of the film, and also in its individual parts, where one person is connected to another person. It is a brilliant idea that all of these women are trapped. So it is a surprise to me that you were able to make that film in Iran.

JP: We talked about The Circle a little bit before, so, let’s see where it comes from… With the film, The White Balloon, I wanted to prove to myself that I can do the job, that I can finish a feature film successfully and get good acting out of my players. With The Mirror I was no longer concerned with proving myself, but, it was the beginning, lets say, of my “movement,” and I started to be concerned with the form. One idea is that in the middle of the film everything will change. Another concern for me was to move beyond the children’s film format. I liked the “softness” of the world of the children, but, I wanted to go beyond that. There is also a kind of flashback to my own youth, when I was in love with short stories. I particularly liked the kind of stories that start at one point and finish at the same point. Also, beginning with The White Balloon, I have a tendency to make “film time” the same as “real time,” where the length of the film is almost the same as the length of time taken by the story. But, this didn’t seem to be possible with the story of The Circle, which was supposed to have four women of different ages. I tried to imply that the four women were actually the same, one woman at different stages of her life. The first story is of a woman who wants to get married; the second is of one who is married with children; the third is of a married woman, a mother, who wants to leave and go on the road; the fourth is of a woman, already on the road, who is about to become a prostitute. In such a closed society, there is no way to escape. So in a very short period of time, we were able to cover a long period of time in one woman’s life, through depicting it in different stages of four women’s lives. So each player hands over to the next player, as it were. The first, young woman is very idealistic, and she is filmed through a hand-held camera. For the next one, the camera is no longer hand-held, but is mounted on a tracking device [a dolly or a truck]. For the next one it is not daytime any more. It is at night. The camera is almost static, and the lens is quite close to the subject. And, for the last one, the camera is not moving at all, and neither is the personage, who is viewed up close. Also, there is very little sound. The film is almost silent, here. There is less light and more darkness. Marriage here is depicted something like a funeral service … Many filmmakers confine themselves to a single style. I don’t do that.

The Circle was a very difficult film to make and to deal with. After it was finished it felt like it would be my last film. But, out of nowhere, the opportunity came to make Offside. Our treatment was very simple, and, we used documentary style, shooting some of the film while the football game was taking place, offscreen.

Offscreen: That’s great! In fact, Offside is the best film I’ve ever seen on football [soccer]. And, it’s in “real time” right?

JP: Yes, all of my films right from the beginning take place in “real time.” Unfortunately, I am not allowed to work now. I have a scenario ready, which is a flash-back to that period of Persian short stories that I referred to before, that I have always dreamed of returning to, and making something of.

Offscreen: But also, your episode of Persian Carpet, “Untying the Knot,” that’s a great example, a perfect example of “real time,” with a single long take, a one shot film. And it is also “political” as well.

JP: When they proposed Carpet to me, I refused. I don’t like this kind of materialistic effort. If I wanted to make a film about carpets, it would be about the beauty of the carpet. I really don’t like the concept of marketing the product. When they insisted, I remembered my childhood, when we had a carpet in the house, and my father had a financial problem, so he took the carpet to be sold. The people there looked just like us, ordinary people. So when I accepted to make a short film for the carpet project, I thought, what could I do? I thought that there must be a single unit of time, a single unit of place, and a single character. With one time, one place and one person, it is better to have only one shot.

Offscreen: I am learning so much, this is so fantastic, and I’m going to look at The Circle again after what you have said. The film is even more impressive to me, now, and I will use what you have said the next time I teach the film.

JP: [smiling] We learn all of this from teachers like you.

Offscreen: Thank you very much, and, I hope you get to make another film, soon.