Homosexuality and the Italian Spaghetti Western

To say that homosexuality in Italy is a complicated issue would be an understatement. To claim that some of the films from the country’s most popular genre, the Spaghetti Western, contain homosexual tendencies would be unexpected but as this essay will suggest, not inappropriate. The country’s strong tie to Catholicism kept all things queer, literally in the closet for centuries. Fortunately, Italy, like elsewhere, benefited from the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s and witnessed a rise in the demand for gay rights. While this initial awakening had insurmountable results, for example the 2000 World Pride Parade in Rome, its effects can be seen across many fields. Perhaps more important than 200,000 lesbians and gay men marching on the Italian capital, the 1960s and 1970s sparked a social discourse in Italian criticism defined as queer (Cestaro 1). These new studies on same sex desire in the Italian tradition not only reveal the influence of a complex history but trace homosexuality back to the beginnings of Italian culture. Seen mostly in art, both visual and literary, the queer tradition in Italian culture is rooted in homoeroticism. Spaghetti Westerns, some more than others, are not excluded from this tradition. Nor are they excluded from an American influence. Similar to the changing view of homosexuality in the Italian tradition, the American West has witnessed a recent re-evaluation coined as “The New Western History” characterized by redefining the Western hero as queer (Packard, 7). Combined with the Italian homoerotic tradition it is not surprising that Spaghetti Westerns can hint at homosexuality. However, this representation of homosexuality is on a sliding scale and the three films to be discussed demonstrate a multitude of its possible positions. Ranging from the homosocial in Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (1966) to the homoerotic friendship in Damiani Damiano’s A Bullet for the General (1966) to the homosexual in Giulio Questi’s Django Kill…If You Live, Shoot! (1967), the films collaboratively convey a country’s fledging relationship to the notion of fixed identity.

Defining a queer tradition in Italian culture, as Gary Cestaro’s book “Queer Italia” attempts to do, is a difficult task. Yet as stated above, lying at the very heart of this tradition is homoeroticism. Rarely contested, homoeroticism is often seen as an extension of homosociality. Referring to same-sex relationships that are not of a romantic and/or sexual nature, for example, a heterosexual male who prefers to socialize with men may be considered a homosocial heterosexual; homosociality implies neither heterosexuality nor homosexuality (Summers). On the other hand, homoeroticism refers to same-sex erotic expression that is subtler and less explicit than overt depictions of homosexual situations and behaviour. Both of these are part of a long, complicated history in Italy characterized by the positioning “between the classical and the Catholic, between ancient organizations of human sexual activity that left some space for same sex desire and Christian efforts to redefine and delimit” (Cestaro, 1). It is becoming increasingly accepted that the ancient practice of adolescent boy love flourished in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. One need only to look at the some of Sandro Bottecelli’s paintings or Michelangelo’s sculptures. Casting reflections throughout the Italian tradition, this example of the homoerotic was not only accepted in Italy but considered the norm until the Catholic Church gained increasing power. Despite this Catholic attempt to heterosexualize Italian culture, Cestaro and others argue that a type of queer canon exists encompassing figures from Dante to Michaelangelo to Pasolini and finally to filmmakers such as Salvatore Samperi (Cestaro, 7). While perhaps not as obvious initially, the three Spaghetti Westerns mentioned above could also fall into this queer canon for they are definitely influenced by the rich history of the homoerotic in Italy.

Spaghetti Westerns are often subjected to a comparison with their American counterparts. According to D. Eleftheriotis this conventional genre criticism is not sufficient for understanding the Spaghetti Western for it does not include questions of national identity and nationhood. Using these questions the differences between the American and Spaghetti Western become clear; for example, Spaghetti Westerns carry weightier political issues and a distinctly different visual aesthetic. Nevertheless, the fact that the Western genre, literary or filmic, originated in America cannot be ignored; “the emphasis on landscape, on demographic mobility; the focus on brutality, brigandage, revenge, and criminality; the decomposition of villages, the ambiguous role of the Catholic Church, and the stark competition for economic power – all are conditions that inhere in Italian folklore but can be grafted to prevailing representations of Americanism” (Landy, 184). More so, lying at the very heart of any Western tale is the hero and even though the Spaghetti Western also redefined the hero, its origin is an American convention. Because of this influence, when trying to understand the Spaghetti Western, it is essential to consider the “The New Western History” and its attempt to balance the traditional views of the American West with more diverse representative perspectives, specifically a queer perspective. With this consideration the image of the cowboy, both American and Italian, garners a new interpretation: “In other words the cowboy is queer: he is odd, he doesn’t fit; he resists community; he eschews lasting ties with women but embraces rock-solid bonds with same-sex partners; he practices same-sex desire” (Packard, 3).

Considered the father of the Spaghetti Western, Sergio Leone perhaps best exemplifies this combination of a queer Italian and American Western tradition. After working as a second unit assistant director on William Wyler’s Ben Hur (1959), a film known for its gay subtext and extreme homoeroticism, Leone’s directorial debut The Colossus of Rhodes (1961) would also be a mythological film. More specifically however, these mythological films belong to the peplum filone, the ‘sword and sandal’ films extremely popular in Italy in the early 1960’s. Characterized by, more often than not, a professional bodybuilder in the principle role, peplums glorified the muscular male body much like American “physique” magazines of the same decade. Already linked to homosexuality at the time, the bodybuilder characters, with their revealing loin clothes and well-oiled flexed muscles “mirroring the actions of an erect penis” became objects of same-sex desire (Ormrod). Steeped with not so subtle hints at the classical acceptance of homoeroticism in Italy, these films and their archetypal characters transcended into the genre Leone created with A Fistful of Dollars (1964). If the implication of Leone’s history with homoerotic mythological films is not strong enough for a queer interpretation of his work surely his well-known love for early American Westerns on television and in film solidifies it.

Confronted with the homoerotic from an Italian and American tradition it is not surprising that Leone explores “the theme of friendship that can spring up between two men” in The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly (Frayling,173). While strong defenders of their bachelorhood and independence, Tuco (Eli Wallach) and Blondie (Clint Eastwood) engage in a relationship that challenges heterosexual norms. “Based on economic competition but also on something else that entails grudging admiration and respect, if not affection and tenderness,” their ambivalent relationship is central to the film (Landy, 190). Obvious examples of homosocial men, Tuco and Blondie are rarely far from each other’s side. Even if they are almost killing each other at times it is clear that their friendship is essential “to ensure their survival in a hostile wilderness” (Packard, 5). With no traces of femininity, of what Leone calls “an obstacle to survival” the film takes on a homoerotic tone similar to that of the Italian tradition (Frayling, 128). It is not overtly sexual at all, but hints of affection between the two men definitely exist. When Tuco is receiving a horrific beating at the hands of Prisoner Guard Wallace, Blondie stands outside with the other prisoners; the troubled look on his face combined with the gentle, moving music, suggests a shared emotional intimacy between him and Tuco. The film’s conclusion solidifies their friendship as Blondie, the archetypal rebel, reveals his loyalty to Tuco by killing Angel Eyes (Lee Van Cleef) instead. A friendship that can only exist in the wild, Tuco and Blondie’s relationship is such an emulation of classic homoeroticism that it often goes unnoticed. Nevertheless, a pluralistic reading of the genres history and knowledge of Leone’s influences push the queer element to the forefront.

Noted as the first Spaghetti Western with an implication of homosexuality A Bullet for the General is a more obvious example of what Leone’s film hints at. Tate (Lou Castel), the American in Mexico during the Revolution, embodies the outsider in more ways than just his foreignness. His polished costume including white suits, gloves and shiny shoes resembles that of the dandy or homosexual in early cinema. Unable to create convincing language about the worthiness of women for his passions he blatantly eschews sexual encounters with the opposite sex when Chuncho (Gian Maria Volente) asks him about it (Packard, 7). As mentioned above though this is not atypical of the Spaghetti Western. In a world built upon bachelorhood and freedom a man’s aversion of women is admired. As a result, “Gradually, El Chuncho becomes fascinated by the Gringo’s cool efficiency, his knowledge of firearms, and lack of passion for anything except money, and almost despite himself, he begins to strike up a friendship with him” (Frayling, 223). An example of ‘male marriage,’ Tate and Chuncho’s relationship is not only rife with instances of the homoerotic but of a kind of homoeroticism found in 19th century American Western literature characterized by “cowboys who seek partners whose essence lies in difference of race, of national or tribal allegiance, but not difference of gender” (Packard, 14). Thus, the American counter revolutionary and the Mexican bandit engage in a relationship of mutual affection and physical closeness. The first and perhaps the strongest instance of their homosexual relationship occurs during the raid of Don Philipe’s house. After admiring Tate inspect and play with the gun hanging from the wall (a gesture screaming with sexual symbolism) Chuncho kills one of his own men in defence of Tate. This demonstration of loyalty is surprising but when acknowledged it makes the recognition and understanding of later homoerotic affection clearer, for example when Chuncho deserts the peasants to rejoin Tate, and when he nurses Tate back to health when he has malaria. While essential for each other’s survival, like Blondie and Tuco, Tate and Chuncho also share an unspoken affection for each other that once again is only acceptable in the wild. As odd as it might sound even Tate’s death can be interpreted as part of a homosexual discourse. It fulfills Russo’s conclusion from his study The Celluloid Closet that, “In essence, in traditional cinema, the only good homosexual is a dead homosexual” (Cestaro, 169). Although Chuncho himself kills Tate, ending their deep friendship, his reason for doing so is open for an interpretation that goes beyond killing him because he represents capitalist imperial America. In essence Chuncho eliminates two outsiders, the gringo and the homosexual.

While The Good, The Bad and the Ugly and A Bullet for the General offer representations of the homosocial and the homoerotic, these representations are in the form of subtext. The relationships between the leading cowboys in both films warrant a discussion of the history of homosexuality in the Italian and Western tradition but can be and still are argued against. On the other hand, Giulio Questi’s Django Kill…If You Live, Shoot! is known for its blatant depiction of homosexuality. In this film there is no hero and his sidekick representing homoerotic friendship. Instead the hero is pitted against a Mexican-faction of homosexual muchachos led by Mr.Zorro (Roberto Camardiel). Questi’s decision to represent the hero’s enemies as homosexual was definitely a conscious one due to his past as an anti-fascist partisan fighter. Questi’s clan of black-leather clad muchachos references the Italian fascist military groups known as the Blackshirts. Organized by Mussolini and known for their extreme use of violence and recognizable black uniforms, the Blackshirts were imitated by Hitler when he created the Brownshirts. Also known as the SA or Nazi Stormtroopers the Brownshirts have long been associated with homosexuality due to the more or less open homosexuality of its chief of staff Ernst Rohm (Wikipedia). The correlation between these two groups and Questi’s Blackshirt muchachos could not be more obvious. Mr.Zorro and his clan of cowboys are clearly homosexual. They embody the classical Greek and Italian tradition of adolescent boy love from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance but instead of one same sex object of desire, Mr.Zorro has an entire clan and there is no mistaking either of them as heterosexual. Mr.Zorro is a grandiose figure of the dandy with his feminine gestures, polished attire and lines such as, “You don’t know how much my muchachos mean to me, with their shiny black uniforms.” Similarly, the muchachos ride around on white horses in tight and overtly sexual black uniforms.

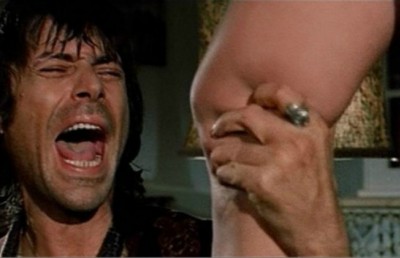

If the characterization of Mr.Zorro and his clan were not enough to make the homosexual reference stand out Questi drives the point home with the scenes of Evan (Raymond Lovelock) and the hero at their ranch. Possibly a homosexual, or at least an outsider, Evan is unmistakably raped off camera after the huge feast. Dividing the erotic lives of men in the West into the physical and the emotional, Packard introduces the term ‘sex hunger’ as an aspect of physical eroticism. Accordingly, as a result of heavy meat diets cowboys shared a ‘sex hunger’ that invited a kind of situational homosexuality (Packard, 14). The feast scene and the subsequent off camera rape of Evan undoubtedly demonstrate this quite blatantly as numerous shots of the muchachos devouring a pig and even a banana flash across the screen during the feast. The entire night at the ranch is highly sexualized this way and concludes with shots of drunk, satisfied sleeping muchachos sprawled on the table and each other. Evan’s suicide the next morning solidifies his off-screen rape as well. Once again the homosexual dies but this time because homosexuality is seen as an unliveable condition resolved only by the Italian patriarchal imperative: “Nothing remains for a man who had done such things but to shoot himself with a revolver” (Cestaro, 169). Similarly the gruesome deaths of the muchachos and Mr.Zorro can be read as an elimination of homosexuality. In Questi’s bizarre vision of the West queerness is not the deep loyal homoerotic friendship between two cowboys. Like most genre conventions in the film he radically changes the homoerotic to something strange and grotesque, mainly homosexuality because of their connection to fascism. In this way Questi’s portrait of the homosexual is a homophobic one and one representative of the Christian condemnation of homosexuality in Italy. Nevertheless, its appearance in the film still emulates the history of homoeroticism in both the Italian tradition and the Western.

Gay cinema in Europe has existed since the 1930’s and even has a history in Italian film, for example most of Visconti’s neo-realist oeuvre contains an under current of homoeroticism. It could be assumed that gay cinema, which gained popularity in the 1960’s and 1970’s, would have prompted viewers and critics to recognize the homoerotic in Spaghetti Westerns at the time of their production. But as articulated above this was not the case. A queer reading of the Spaghetti Western was hindered by Catholicism despite the existence of a classical acceptance of same-sex desire. Modern and pluralistic studies of homoeroticism in history has not only helped identify queer elements in the Spaghetti Western but has unearthed these elements from an Italian and American Western tradition. And for a genre characterized by both strong national identity and American influence, the inclusion of homosexuality in its discourse seems most appropriate. The representations of homosexuality in these films may be subtle at times yet that is of the nature of its representation in the arts, especially film. The point remains that they exist and this existence expands upon the importance of the Spaghetti Western in Italian and film history.

Bibliography

“Blackshirts.” Wikipedia. 26 November 2007.

Cestaro, Gary. Queer Italia. New York : Palgrave MacMillan, 2004.

Frayling, Christopher. Spaghetti Westerns : Cowboys and Europeans from Carl May to Sergio Leone. London : Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1981.

GLBTQ: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bi-Sexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. Hank Summers.2005. glbtq.inc. 27 November 2007.

Landy, Marcia. Italian Film. Chapter 7 : History, Genre and the Italian Western. Cambridge : Cambridge University, 2000.

Ormrod, Joan. “Issues of Gender in Muscle Beach Party (1964).” SCOPE. Dec, 2002. Manchester Metropolitan University, UK. 16 December 2007.

Packard, Chris. Queer Cowboys and Other Erotic Male Friendships in Nineteenth Century American Literature. New York : Palgrave MacMillan, 2005.