Home Entertainment and Significant Culture: On An Education, Away We Go, Dark Matter, Margot at the Wedding, Michael Clayton, No Country for Old Men, The Secret Life of Bees, A Serious Man, The Stoning of Soraya M., What Doesn’t Kill You, and other films

It is wonderful to see films such as Bliss, The Burning Plain, The Constant Gardener, Crazy Heart, Easy Rider, Eve’s Bayou, Girl with a Pearl Earring, The Grapes of Wrath, Happy Together, Heights, High Noon, The Hustler, Islands in the Stream, Lord of the Flies, A Mighty Heart, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Moon, Push, The Reader, Sidewalk Stories, The Sting, Strange Days, Tennessee, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and We Own the Night. It can be useful to see films such as Birth of a Nation or Raging Bull, even if one does not like them—if only to understand film history or other people’s tastes. One year follows another, and the films keep coming; and that is a fact both mundane and profound, as we discover films that are disappointing or brilliant, unaffecting or moving, redundant or original, and various combinations of these qualities and more. It can be hard to know whether film criticism is still important. With film available to us in different mediums, at varying times, for repeated viewings, and subjected to the commentary of millions thanks to the internet, rather than a few print, television and radio critics, why should the discourse of a few claim priority?

With the insight of directors and filmmakers readily available through audio commentary attached to the film works themselves (in digital video disk presentations), as well as creator testimonies given in print, on television, and through the internet, what secrets remain for disclosure? Some film critics—desperate for the maintenance of their own careers—refuse to take such questions seriously, though these questions are precisely the ones that have made their existence so precarious; but, that dismissal by small-minded professional critics does not really matter, as most of the film viewing public ignores their film reviews and their assertions of self-importance. It is the films that matter—it has been, always, the films that matter.

It is not that film criticism cannot offer insights into both the creative process and the finished work. It has. Film criticism, years ago, drew the attention of the public when films were new, original, strange—and required special attention and understanding. Thanks to the success of that film criticism (especially the criticism of writers such as James Agee and Pauline Kael), as well as fascination with the glamour of film, knowledge of film practices and much else in the cinema world is more common now. Consequently, when we speak of film in person, in print, in public, it is to share our own enthusiasm, rather than to insist on our own power as privileged viewers. (The exceptions, of course, are the provinces of experimental film and academic film discourse, with their references to very unusual practices and to theory and philosophy; and the audience for that kind of thing is likely to be small, always.) Most of us, when we discover a particular beauty or a unique idea in a film, we celebrate that film. We go on, celebrating the films…

This year, 2010, I have seen a good number of films that I had missed, seeing them thanks to digital video disks and the home entertainment market: they include An Education, Away We Go, Dark Matter, Defiance, The Fountain, In the Valley of Elah, The Last Kiss, Lions for Lambs, Local Color, Margot at the Wedding, Michael Clayton, No Country for Old Men, Rachel Getting Married, The Secret Life of Bees, A Serious Man, The Soloist, The Stoning of Soroya M., There Will Be Blood, 3:10 to Yuma, and What Doesn’t Kill You.

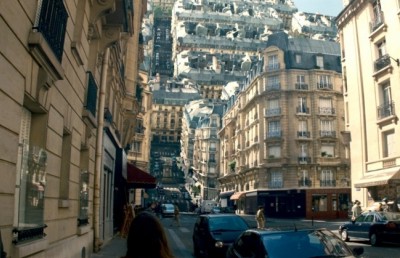

An Education – An Education follows an English girl’s infatuation with an older man and his “interesting” lifestyle of nightclubs, art auctions, and trips to Paris, an infatuation that, for a time, blinds her to the necessities of her own life—the need to finish her grade school education and go on to university. It is a film about illusion and deception—her lover is not the man she thinks he is. He is a consumer and not a creator, and a fantasist rather than a truth-teller. He has seduced her, as he has others, with the aura of sophistication rather than its true content. Carey Mulligan, directed by Lone Scherfig, is perfect as the girl—she is hopeful, smart, and direct, and she confronts her elders with honesty but she is not vicious. She asks, What is the purpose of education? Peter Sarsgaard is the lover; and he is charming, and first appears serious, though he is immature; and the girl does not see that he is extending his own youth through her. The older lover’s friends are played by Dominic Cooper (puckish, tough, sensual) and Rosamund Pike (beautiful, but intellectually dim—a new kind of character for an actress who has played more authoritative roles). The school girl wants to know what the purpose of education is, and she is not given a good answer by her teachers or parents—though, it seems, she learns it for herself: one purpose is to be able to distinguish the true from the false.

Away We Go – Away We Go by director Sam Mendes, is a film that focuses on the marriage, impending pregnancy, and search for a new home by a thirty-something couple, a loving, quirky, white male, Burt (John Krasinski), who works in insurance, and a patient but serious biracial (black) female, Verona (Maya Rudolph), who works as an anatomy illustrator. We see the loving couple as they travel to visit acquaintances and sites, looking for the place in which to settle to have and rear their child. They meet a funny, half-crazy woman who used to be Verona’s boss, and college friends who have adopted children but are still trying to have a baby, and a presumptuous, judgmental New Age young feminist woman who grew up with Verona’s sweetly goofy husband. John Krasinski is charming and Maya Rudolph unique and moving (she has a core of sanity); and the film is one of the most believable views of American life. There are values embedded in these people’s lives, but what we see are the people.

Dark Matter – Dark Matter, directed by Chen Shi-Zheng, is focused on a brilliant Chinese student who is first embraced then rejected by an established professor for the inventive work he promises to do, when the student’s ideas go against that of the professor. The student, acted by Liu Ye, is intellectually gifted but personally naïve (he is clueless about academic politics). The student’s problem is that he does not wait until after graduation to critically evaluate his professor’s work. The scenario resonates as it is about work and power. When can you afford to disagree with those whose approval can directly affect your career, your life? Aidan Quinn plays the prideful professor whose cold disapproval isolates and fails his student—though the professor himself had gone against his own mentor in the past. Meryl Streep plays a flighty, smart, well-intentioned woman who befriends the student: she is also a picture of the limits of white liberalism (her personal kindness and perspective do nothing to change what happens). Streep, good in many things (Julie & Julia, Lions for Lambs), is to be commended for giving herself to this very intelligent, small film that presents an unpopular truth: vanity comes before knowledge.

Defiance – The story of Jewish suffering is well-known and this film works powerfully in its presentation of a group of practical, resilient, tough Jews who are attacked by Nazis and move into a forest to survive, developing defenses, shelters, work and food-gathering details, and sexual relationships that sustain them. The Edward Zwick film is both dream and nightmare: showing how a community is created and survives threat. It is also a story of love and family, focusing on brothers—their devotion and conflicts—and the women they meet. At one point, when someone dies and the death is commemorated, words are spoken asking for the special nature of Jewish identity—Jewish holiness, being a chosen people—to be removed. In one instance after another, sentimentality is repudiated and a new passion and strength discovered. These Jews—led in the film by characters played by Daniel Craig and Liev Schreiber—fight and fight well.

The Fountain – There are films that are experimental and original, though they are not sold that way or discussed that way. There is another, official kind of experimentation, in which artists use the same kinds of devices and tropes over and over again to suggest that they are refuting convention, doing something transgressive (academic scholars love those); and Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain is not that kind of film—it is much better than that, more original. The Fountain is about a search for health and lasting life, for immortality, focusing on a man and woman who met hundreds of years ago, and who live long into the future, continuously reincarnated, while he pursues the tree of life, hoping to bring something of it back so his beloved may live. Hugh Jackman and Rachel Weisz, two attractive and interesting actors, play the leads: he is brave, inventive, and in his devotion obsessive, and she is charming, possibly eccentric, and smart and strong. The film is historical pageant, morality tale, medical drama, film noir, science fiction, fantasy, and wisdom sharing; and there are images in it that I do not think have been seen before (Jackman as a full grown, bubbled meditating star child is one image, and a seemingly pulsating—breathing?—tree is another). Here, it is possible to see transcendent consciousness trying to make transcendence permanent: and there is something both beautiful and horrifying in that.

In the Valley of Elah — A father believes in family, duty, and military service and passes those values on to his son, a legacy his mother sees but does not oppose; and the son goes to war, and the war disturbs the son, changes him: instead of being a hero, he becomes barbaric—and that is the story that Paul Haggis’s In the Valley of Elah tells, featuring Tommy Lee Jones and Susan Sarandon as the boy’s parents. Tommy Lee Jones is notoriously tough, but here we see a rotting pain that begins in him as he learns about what his son has become; and Susan Sarandon’s grief as the mother allows her to tell her husband the truth about his influence on their son. Sarandon has brought many significant moments to film, and this is one. Why must the fathers kill and the sons follow them, only to die?

The Last Kiss – Zach Braff has his charm (sweet, funny, sensual), but the revelation in this Tony Goldwyn film is Jacinda Barrett as his pregnant girlfriend: she has the strength—in body, emotion, and spirit—of a woman who lives in a world of ambition, struggle, hope, passion, and pain, the world most of us know. When Braff’s character becomes involved with a younger woman—his momentary crisis before he commits to Barrett’s character—she comes at him with full force and there is a moment when the viewer believes she just might injure him. It is fascinating to see genuine physical threat in a woman’s performance—not simply because she is carrying a knife or gun but because she is angry, strong, and willful enough to hurt a man. Jacinda Barrett’s character (sane, loving, practical on her best days) is admirable, believable—as real as a film character can be. The other characters in the film are also young people who are beginning to face mature responsibilities; and this is one of those films that might grow in resonance for a generation.

Lions for Lambs – Lions for Lambs, directed by Robert Redford, is an intelligent film with a liberal perspective, presenting American military adventures from the view of an ambitious senator, a longtime journalist, a professor and his students, who surprise the professor by volunteering as soldiers. The cast is strong, especially with Tom Cruise as the senator, Meryl Streep as the journalist, and Robert Redford as the professor. What is the responsibility of each in relation to educating citizens, and helping them to understand military action? The film’s dialogue is logical, orderly; and I think that is a good thing, though it has become rarer in film than it used to be (so much of contemporary dialogue is fragmented, imprecise, suggestive, without complete thoughts or arguments—and because that replicates the ignorance and incoherence of some people’s private conversations, they see that faulty articulation as authentic). This is a film that presents different sides, something that alone reminds us that we are all part of the same society—and must renew civil discourse. The film’s strengths are in its presentation of its characters as dynamic actors in public policy, people with authority and imperfect wisdom.

Local Color – Abstract art versus representational art. Youth versus age. Love versus hate. George Gallo’s film Local Color sets these paradigms in motion when an aging representational painter is sought by a young man who knows and admires his work and theories. The older man has an associate, an art curator and critic who likes experimental work, but whose taste is quite questionable (he ends up raving about the work of children). The painter has a next door neighbor, a beautiful sad woman, a poet, who brings him pies and helps with the house’s decoration, and the younger man becomes infatuated with her. It is a very effective cast, with Armin Mueller-Stahl as the angry, cursing older man and Trevor Morgan as the younger man, a working class boy who has many gifts, none of which have made him crazy yet. The young Morgan—playing the boy as masculine and sensitive, modest and direct, ambitious and grounded—is a genuine find in a film that offers beauty, clarity, emotion, and humor.

Margot at the Wedding – Mother as destroyer may be a classic subject: the one who gives birth also brings endless pain. Here, Nicole Kidman plays that mother, a writer who exploits her family in her work and denies it (she seems to think that her interpretations render the characters something other than her family—but for an ordinary person, interpretation is nothing more than opinion or criticism in the crudest rather than higher sense). Margot, who travels with her son to her sister’s wedding to a man Margot does not know or trust, thinks that truths must be spoken and she is the one to speak them; and she believes in significant intimacy, as long as it is on her terms. This mother has a dangerously close relationship with her son, something they both seem to know, here complimenting him, there denigrating him (they do not sleep in the same bed without a pillow between them). This mother can crush her son with a few words (for her, it is just a moment—for him, probably, these words will last a lifetime). Her relationship with her sister (Jennifer Jason Leigh) is not dissimilar; and they do things that rile and sooth each other, as when the writer comments on her sister’s averted gaze, and the sister challenges Margot to climb a tree, from which, once climbed, Margot is too nervous to climb down from. With the sisters, disturbance seems to last longer than balm; and, it is sometimes obvious that they do not understand that they are not the same kind of person (Margo idealizes and demonizes; and the sister accepts). Noah Baumbach’s Margot at the Wedding, a film with no wasted scenes or shots, a film without fat, is one of those films that feel true. Is it too much of a confession to say that I have seen this film a bunch of times and would not mind seeing it a few times more?

Michael Clayton – Law. Money. Sickness. Deception. Some of the controversial areas of American life are touched in this legal thriller directed by Tony Gilroy, starring George Clooney and Tom Wilkinson and Tilda Swinton. Wilkinson plays a brilliant lawyer assigned to a high-profile corporate responsibility litigation case, involving ordinary people who were made sick by a commercial product; and the lawyer, dedicated for years to the case, has begun to grow crazy (and in some ways more sane), becoming sympathetic to the complainants. Clooney plays a law firm fixer who is tasked with getting his crazed colleague Wilkinson in hand, something the brittle corporate official Swinton—dangerously, unfortunately—does not trust him to do. The subject of the film, corporate malfeasance, is the kind of thing we have read about in newspapers for years; and the film, though fiction, is confirmation and elaboration. What is worse—that films tell us that powerful people will do anything to get what they want and keep it, or that we can easily accept this message in film after film? Here, Clooney plays one of those failing, glamorous men who can see his best days behind him, and an uncertain future, and he is given one more chance to prove his value: he does. The premise of this film—the corporate cover-up of a faulty product—is not new but the execution is superb.

No Country for Old Men – We grant realism a special place, assuming its seriousness, and yet the closer films come to replicating an “ordinary” life the smaller that life can look. In the Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men, a brave, smart man but ordinary man (Josh Brolin) does an understandable but foolish thing, stealing a suitcase of money following his stumbling upon the remains of a violent shootout. The treasure-finder expects someone to look for the money, though he does not anticipate that the person who does will be the lethal factor he proves to be (a methodical sadist, played by Javier Bardem). For a time, we root for the ordinary man, but after we learn his fate, late into the film, a fate given no dignity, it seems the most predictable thing. Something in the human heart sinks. Josh Brolin as the smart, sexy, luckless man, and Javier Bardem as the inventive killer, and Tommy Lee Jones as the old, well-intentioned sheriff, are good. The film feels elemental, and I enjoyed it while watching it—and then I doubted it.

Rachel Getting Married – It took several viewings for me to like the usually beautiful and charming Anne Hathaway in this Jonathan Demme film, Rachel Getting Married, in which Hathaway plays a famous druggy responsible for her younger brother’s death. Her character Kim’s consistent selfishness is thoroughly repellent (of course, if she were a writer or a painter, I would be a little less repelled. My bad). Yet, the young woman Hathaway plays feels genuine remorse and that is the best thing that can be said for her (one sees Kim’s remorse most in her addiction counseling meetings, in which she is fully present, and grappling with the truth). Kim exists in a modern, multicultural world, with interracial marriage, jazz, and blunt talk, a world we see when she returns home for her sister Rachel’s wedding. The wedding itself has a deep, eccentric and organic allure. Bill Irwin, as the father of Kim and Rachel, is strong, as is Debra Winger as their mother, but the nontraditional actors playing Kim’s stepmother and new brother-in-law disappointed me—they did not bring developed resources, interpretations, or mastery to their roles.

The Secret Life of Bees – The Secret Life of Bees, about death and guilt, flight and refuge, family and spirituality, is a very sentimental story, but it also happens to be a genuinely literary story, with characters, symbols, and plotting worth consideration, and that work well in film. The story is set in the mid-1960s, at the time of the American civil rights movement, a time when progress is being sought and made, but the forces of reaction and repression are still very active. Rosaleen, a black woman—a farm worker and caretaker of a white girl—gets in trouble, asserting her basic intelligence on her way to register to vote. Based on a novel by Sue Monk Kidd, the film, directed by Gina Prince-Bythewood, focuses on an orphaned white girl, Lily (Dakota Fanning), who runs away with her black woman caretaker, Rosaleen (Jennifer Hudson), to a town the girl’s deceased mother had visited, the girl hoping to find out something about her mother. The white girl and black woman go to the town, in which they meet a beekeeping, honey-making black family—one sister is the matriarch (Dana “Queen Latifah” Owens), one is the artist-activist (Alicia Keys), and one is half-mad and grieving (Sophie Okonedo: Okonedo is one of the most humble, protean talents. Apologies to her for taking so long to learn how to spell her name). The house contains a black Madonna, an old wood statue of a black woman with a raised fist, around which spiritual services are held; and the woeful sister maintains a wailing wall, where she leaves notes of her griefs. What are the ways in which we can respond to injustice in the world? With forgiveness and practicality, creativity and activist anger, or pain and possibly capitulation; and those possibilities are what the three sisters represent. The white girl and a black boy become friends and get in trouble when they go to a movie together. Lily’s cold, hateful father, played fearlessly by Paul Bettany, looks for her (though her father is alive, his attitude renders her an orphan); but she has found a home with the black women. Considering this film contains a cast of leading African-American performers, Queen Latifah, Alicia Keys, Jennifer Hudson, one might have expected that it would have garnered more attention than it has.

A Serious Man – Salty language, drugs, and sexual flirtation are some of the elements used against the clichés of Jewish earnest sensibility in this family comedy, focused on a physics professor whose wife is involved with another man and whose children are growing as alienated. Rock music is a significant reference, an embodiment of the changing times affecting all. The physics professor visits rabbis, hoping to get help in understanding what is happening in his life; and those are amusing digressions, but he does not get the insight or solace he wants. His visits to lawyers may be more helpful, in terms of practicality (start a separate bank account, he is told). I do not know if I am the ideal viewer of this Coen brothers’ film: although not Jewish, I enjoy films featuring Jews and films with Jewish themes, so that it is not what I mean—rather, some people have commented that the film is partly a critique of the physics professor as someone who could be but is not a serious man, but I have no particular problem with him. I think he is a decent man, and that his work is significant, and that if his relationships with his wife and children are flawed then they, as much as he, have responsibility for that. As well, if he seeks wisdom from others and they have none to give, whose fault is that? Is he to be held responsible for lacking the wisdom that no one has? Why do bad things happens to us? You answer that.

The Soloist – Robert Downey Jr. and Jamie Foxx give good performances as a journalist and the gifted, homeless musician he befriends, but what I like most about this film is the Los Angeles it presents. I imagine people who live there must appreciate the love and respect with which their city has been presented. The locations alone give this Joe Wright film an epic scope: we are seeing wealth and poverty in this film, but the locations remind us of the many stories, the many fates, that are possible in a great city. My response to the story the film focuses on is rather mixed—I think journalists do a service by investigating neglected lives, especially the lives of unfortunate artists, but it is wearying to see one black man after another who lacks both luck and wisdom. Some important and even transcendent part of the homeless musician survives in his ability to make music, in his dedication and skill—but I regret, and regret profoundly, the absence of wisdom.

The Stoning of Soraya M. –The Stoning of Soraya M., about a woman whose cruel Middle Eastern husband is infatuated with a girl whom he wants to marry, and as he has some social power—he can influence the Iranian village chief, and the girl’s father who has come into trouble with the law—the husband is able to easily solve his problem: how to get rid of his wife, the mother of his two sons? Watching the film is like watching a Greek tragedy. It has that elemental force, and that sense of terrible fate. The wife’s aunt hears gossip, and she knows trouble is coming—and she tries to warn her innocent niece to be careful, but after the niece begins to work outside the home—for a widower, for money she needs—the wife is subject to new accusations. Her husband can accuse her publicly of adultery and get the whole community to participate in her punishment, in her murder. This is an unblinking portrait of human evil. Based on a true story, this Cyrus Nowrasteh film is one of the deepest, persuasive, and significant films I have seen in years. By telling the facts, and illustrating them with great acting, it stands as an argument for the education, financial independence, and freedom of women.

There Will Be Blood – Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood, about an oil industry miner who adopts a boy and finds riches, though his heart is no more than slightly warmed by love or money. The madness and malice of selfish ambition are what time and the film reveal. The isolation that spurs ambition can sustain it and render it both successful and meaningless. As the lead character, Daniel Day Lewis creates a monster whose fangs we do not notice until after there is blood on the floor.

3:10 to Yuma – James Mangold’s 3:10 to Yuma, featuring Christian Bale, Russell Crowe, and Ben Foster, is an entertaining western that allows the viewer to admire both the hard-luck farmer (Bale) who takes on a justice system job as escort to a criminal, and the criminal (Crowe), who is charming, and whose gang wants to free him (the gang is led by an eccentric, stylish Foster). The film suggests that a criminal can have sympathy for an ordinary man, indicating a common humanity, but the film ends reminding us—violently—that good and evil are not the same and that evil is relentless.

What Doesn’t Kill You – What Doesn’t Kill You, set in Boston, and about young men whose lives are rooted in poverty and crime, has both grace and grit. I admire its presentation of a city. Directed by Brian Goodman, who lived the life depicted in the film, What Doesn’t Kill You stars Mark Ruffalo and Ethan Hawke as criminal men. Mark Ruffalo’s film character, Brian, is conflicted, tormented by his love for his family and his drug addiction, and less so by his criminal activity. Ruffalo is a beautiful man, a man whose physical and spiritual beauty seem unexpected; and in the film his beauty—his soul—is threatened. (Seeing Ruffalo as a bourgeois doctor dependent on his wife in Blindness, a film set in a cosmopolitan city, reminds one of the actor’s range, and his willingness to reveal a man’s vulnerability.) Yet, it can be disconcerting to watch Ethan Hawke, who began acting as a boy, and who was once both handsome and sensitive: he has lost that handsomeness, and here, playing a man, Paulie, whose spirit has been starved by his attempts to survive, he is not sensitive, though the viewer does believe his character’s affection for his friend Brian—and the viewer appreciates Paulie’s honest response to a young woman infatuated with Paulie (Paulie tells her he is just having fun but cannot make a life with her). Every scene in this film looks good and feels like the truth. What do you do when your resources are few? Suffer. Is it possible to change and to grow? Sometimes.